A baby in the womb has few defenses against industrial petrochemicals designed to kill.

Unborn babies’ nascent metabolic and detox systems lack the means to neutralize toxic exposures. And the placenta, which doctors once thought protected the fetus from most harmful substances, in fact admits hundreds of toxic chemicals. That leaves the fetal brain, which undergoes rapid changes as billions of cells acquire specialized roles and form trillions of connections, particularly vulnerable to neurotoxic pesticides.

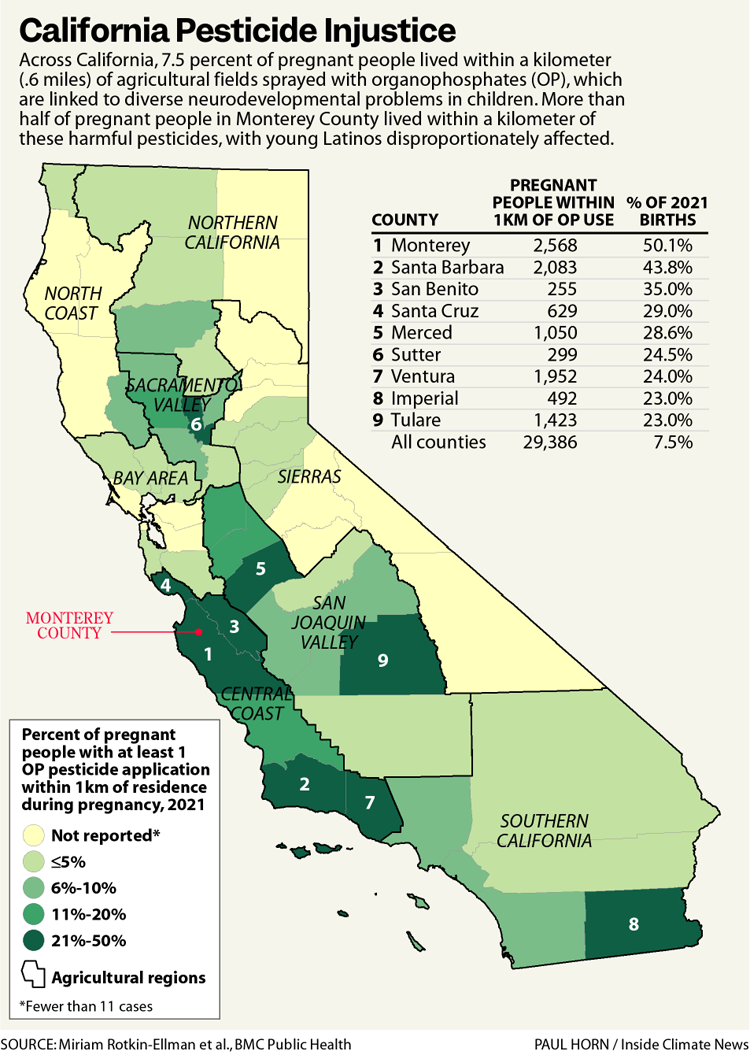

New research shows that some babies in California, a state that prides itself on environmental stewardship, face particularly high risks of exposure to organophosphates, petroleum-based insecticides with strong links to neurodevelopmental problems, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, lower IQ, cerebral palsy and altered brain size and structure.

The study, published in BMC Public Health Tuesday, reported “considerable disparities” by ethnicity, age and region, with Hispanic teenagers in California’s Central Coast—where the chemicals are used primarily on strawberries, lettuce, broccoli and related crops—most likely to live within a kilometer, or 0.6 miles, of organophosphate applications during their pregnancy. In Monterey County, more than half of pregnant people lived within a kilometer of organophosphate-treated fields.

It wasn’t surprising that Monterey, a multibillion dollar producer of strawberries, lettuce and broccoli, was a hotspot of organophosphate use, said Miriam Rotkin-Ellman, an independent environmental health expert and lead author of the study.

“But the magnitude really did surprise me,” Rotkin-Ellman said. “We’re talking one in two pregnancies.”

And the intensity of organophosphate applications was “off the charts,” Rotkin-Ellman said, “way higher than other parts of California.”

At least half of pregnant people in the Central Coast lived within a kilometer of applications ranging from 14 to 69 kilograms, or 31 to 152 pounds, compared to 2 kilograms (4 pounds) statewide. In Monterey County, some applications near pregnant people were as high as 2,422 kilograms, or 5,340 pounds.

“That is a pattern that’s linked to harm for the kids in cohort studies,” said Rotkin-Ellman, referring to research that follows mothers and their children like the CHAMACOS (Mexican slang for “little kids”) study in Monterey County’s Salinas.

It’s worrying to see so many vulnerable people living near “such high amounts of a very toxic group of pesticides being applied,” she said.

Other parts of the state with high pesticide applications don’t have neighborhoods and houses surrounded by nearly year-round intensive agriculture. In Monterey, Rotkin-Ellman said, that combination creates “the perfect storm.”

It’s not unusual to find a profound racial or ethnic disparity associated with pesticide exposures, she said, but “it’s a huge injustice.”

“Environmental Racism!”

At noon on Tuesday in Salinas, farmworkers, doctors, nurses and other community members rallied against that injustice.

“I have been fasting for the past 30 days to bring attention to the poisoning of my community by pesticides and to push Big Ag to convert to organic farming in their fields near schools, near our children,” said Omar Dieguez.

More than 35 years ago, United Farm Workers leader Cesar Chavez compared farmworkers to the canaries that warned of poison gases in coal mines, Dieguez said. Farmworkers and their children demonstrate the effects of pesticides poisoning, like losing IQ points, before anyone else, he said. “That’s got to stop. Ban OPs!”

When Kathleen Kilpatrick spoke with farmworker families 30 years ago as a University of Washington grad student, they all got doused with the organophosphate malathion by a cropduster spraying a nearby orchard. Her resulting studies showed that more organophosphates accumulated inside homes, and even in the carpets of houses far away from orchards, than in the yards.

It’s time to phase out all organophosphates, Kilpatrick said.

As speaker after speaker called on California officials to do more to protect Latino babies bearing the costs of heavy organophosphate use in their communities, people in the crowd shouted, “Environmental racism!”

Antonio Velasco was a migrant farmworker when he decided to go to medical school to serve his fellow farmworkers and community. He treated his first group of farmworkers exposed to organophosphates in 1980, and later helped secure the first ordinance requiring growers to post warning signs when they spray pesticides.

Pesticide poisoning is not just an issue for farmworkers, although they are the largest affected group, Velasco said. “It is a problem for all inhabitants of communities in the Salinas Valley and rural California. It is time that we place the value of a healthy population above the profits of the petrochemical industries.”

“Chemical Cousins” of Nerve Gas

Organophosphate pesticides kill by inhibiting an enzyme critical for normal nerve cell communication and function in both insects and humans. When chemists discovered this mode of toxic action in the 1930s, they harnessed the chemicals to make sarin and other nerve gas agents, which Rotkin-Ellman calls “chemical cousins” of organophosphates.

At high enough concentrations, the pesticides can cause seizures, muscle spasms, confusion, dizziness, paralysis and death.

Concerns about the neurodevelopmental risks of chlorpyrifos, long one of the most popular organophosphates, led the Environmental Protection Agency to ban residential uses in 2001. California prohibited nearly all agricultural uses of chlorpyrifos in 2020, based on evidence from the decades-long CHAMACOS study, a similar study of residential exposures in New York City mothers and their children and studies in animals.

California’s ban of growers’ favorite insecticide gave Rotkin-Ellman and her colleagues the opportunity to see how many prospective mothers lived near other harmful organophosphates.

She collaborated with researchers from the CHAMACOS study, run by the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Environmental and Community Health, and the nonprofit Public Health Institute’s Tracking California program to see if the volume of applications changed and, if so, where and who was most affected.

The team used birth records to get pregnant people’s addresses and obtained data on organophosphate use from California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation. They combined the datasets to determine how much of the insecticides were applied within a kilometer of people’s homes, a distance often used as a proxy for exposure.

They found that only growers in the Central Coast increased organophosphate applications between 2016 and 2021, even as statewide use dropped by 54 percent. Monterey County boosted applications by 26 percent.

Statewide, more than 29,000 people lived near applications of as many as six different organophosphates during their pregnancy. Pregnant teenagers of Latin American descent were not only most likely to live near treated fields but were also exposed to the highest levels.

The study looked just at potential exposures at home, but most people probably face much higher exposures, Rotkin-Ellman said.

They may work in the fields at some point during their pregnancy, and be exposed either from applications on neighboring fields or near schools or other sites in the community, she said. People may also consume pesticide residues on food. Plus, if a pregnant person’s partner works in the fields, they could bring home residues on their clothes and shoes.

“Organophosphates are really notorious for being tracked in on people’s shoes, and sticking in rugs years later,” she said.

The finding that pregnant people, particularly young pregnant people of Latino descent, are very likely to be living in proximity to agricultural fields probably applies across the country, said Virginia Rauh, an environmental epidemiologist at Columbia University who was not involved in the research. That’s because most farmworkers live fairly close to the fields and often work in them, said Rauh, who has tracked the consequences of residential organophosphate exposure in hundreds of mothers and their children in the New York City study for 20-plus years.

But it’s prenatal exposure that worries Rauh most.

Neurodevelopment during fetal growth “is profound,” she said, with critical processes vulnerable to disruption occurring into the first few years of life.

“And we know in the case of chlorpyrifos and many of the organophosphate chemicals that they do cross the placenta,” Rauh said. “And we know they reach the fetal brain.”

Cumulative Risks

Organophosphates aren’t the only harmful agricultural chemical applied in large or increasing amounts in Monterey County.

Just as growers there applied more organophosphates as statewide use dropped, they used more of the cancer-causing pesticide 1,3-dicholoropropene, or 1,3-D, as other farmers cut back, which Inside Climate News previously reported.

“The actual harm experienced by folks living in these danger zones is much higher than what we’re estimating based on just one slice of the pesticide problem and one slice of the chemical soup that we know folks are experiencing.”

— Miriam Rotkin-Ellman, lead author of the study

During 2021, when pregnant people in the county lived near high applications of organophosphates, growers applied more than 1.3 million pounds of carcinogens, including more than 780,000 pounds of 1,3-D.

It’s “incredibly important” to name the cumulative burden borne by pregnant folks because pesticides are only one of the many different threats to their kids’ brain development, Rotkin-Ellman said, pointing to air pollution as another.

“If you talk to people living there, they’ll say, ‘Organophosphates? That’s just one flavor of a chemical mix I’m worried about,’” Rotkin-Ellman said. “The actual harm experienced by folks living in these danger zones is much higher than what we’re estimating based on just one slice of the pesticide problem and one slice of the chemical soup that we know folks are experiencing.”

Data recorded by California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation shows a reduction in total organophosphate use in 2020, after the agency eliminated nearly all uses early in the year, said DPR spokesperson Amy McPherson in a statement. “DPR’s mission is to protect people and the environment by fostering sustainable pest management and regulating pesticides,” McPherson said. The agency takes this mission “very seriously,” she said, and will continue to review new data to inform future mitigation and regulatory action.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowStudies like CHAMACOS in Salinas and Rauh’s study in New York show that early life exposures to toxic chemicals like organophosphates can have lasting effects.

“Our New York work really suggests that the long-term neurological effects are persistent,” Rauh said.

Her study took advantage of “a serendipitous natural experiment,” when the residential chlorpyrifos ban happened as the study was well underway. The team harnessed that in a recent study, which identified brain anomalies and motor control problems in children 12 to 14 years after they were exposed.

Regulatory Uncertainty

From a scientific perspective, there is no doubt that organophosphates can harm a developing baby’s brain and lead to multiple cognitive and behavioral problems. But the decision to issue a national ban on neurotoxic chemicals worth billions on the global market rests with the EPA administrator, a political appointee, leading the agency’s decisions to shift with different administrations’ preferences, Rauh said.

The Obama administration was poised to ban chlorpyrifos, a decision that was reversed during the first Trump’s administration, and reinstated during the Biden administration, only to be reversed in court.

While California is one of five states that have banned chlorpyrifos, Rauh said, it is basically available for agricultural use in 90 percent of states in the country.

Organophosphates should be regulated as a class because they have similar well-known and well-documented effects at the molecular and cellular level, she said. “There’s no excuse not to restrict their use.”

Now that the “big baddy” chlorpyrifos has been banned in California, Rotkin-Ellman said, it’s time to tackle the rest of the organophosphates. She and her colleagues recommend that regulators implement stronger buffer zones around residential areas and restrict chemicals like organophosphates that cause similar health problems.

“We need an agricultural system that keeps the people who live close by and work in the fields safe, safe for themselves and safe for their future generations.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,