At 4:20 a.m., the unspeakable, unshakable fear that had been driving them for the last hour finally eased. Dyer was stable, Isenberg announced. If his carotid artery didn’t rupture and he kept breathing—and if the rescue team arrived relatively soon—he would survive.

The sun was coming up. If a bear came their way now, at least they’d be able to see it.

But the rescue operation wasn’t coming together smoothly.

Chase called the police at regular intervals, keeping a log of every call. But a disturbing pattern had emerged. Often, someone new answered the phone, someone totally unfamiliar not only with their circumstances but with basic information like the location of Torngat Mountains National Park, and the fact that a float plane or helicopter was needed to evacuate Dyer.

At 5:30 a.m., an hour and 45 minutes after her first call, Chase gave a dispatcher the phone numbers for Base Camp—the outpost that serves as Parks Canada’s base in the Torngats—and for Alain Lagacé at the Barnoin River Camp.

At 6 a.m., she suggested to another dispatcher that a helicopter be sent from Base Camp for Dyer and that more flares, or a person with a gun, be brought in to guard the group.

A half hour later, someone told her that was what they were trying to arrange.

Although Chase didn’t know it, Base Camp had been alerted at 6 a.m. and was already working on plans, backup plans and backup-backup plans.

Gary Baike, a Parks Canada employee, had awakened a medic, Larry Brandridge, from his tent and told him to get ready to go. Baike and Base Camp manager Wayne Broomfield checked the hiking route the group had filed with Parks Canada and figured out where they might be. When they learned through a dispatcher that a doctor was traveling with the group, the level of intensity ratcheted down “from an emergency to an urgency,” Brandridge said later.

Base Camp consists of a couple of year-round buildings and a few dozen tents for sleeping. Everything sits behind a 5-foot-tall electric bear fence that is connected to an alarm system. Because the camp is surrounded by mountains, the only way in is by boat or helicopter.

On clear days, a helicopter makes regular runs from the camp, taking visitors and park staff to various islands and locations in the park. But everything stops when the weather is bad, as it was that day. The sun hadn’t come up over the hills yet, and everything above 500 feet was completely fogged in. There was no way they could get a helicopter up.

As a backup, they started preparing a speedboat to take Brandridge and Jacko Merkuratsuk, a Parks Canada employee who is also a bear guard, up to Nachvak. The boat trip would be much longer than the helicopter ride, but if the weather stuck around all day, it might be the best option.

At the same time, they dispatched The Robert Bradford, a commercial fishing boat they contracted for the summer, to make the 10-hour trip up to the fjord. Unlike the helicopter The Robert Bradford was big enough to get all of the hikers out together.

Back at the fjord, Dyer woke up occasionally, murmuring thank-you to whoever was with him at the time. Isenberg occasionally barked orders—asking for a towel, or water or a bottle for Dyer to urinate in. Moments later, a hand would reach under the tent, holding whatever was needed.

The others kept watch and stayed busy heating water for tea or coffee and preparing food for anyone who was hungry. They took turns carrying the flare guns and keeping watch.

By 7:30 a.m., the clouds were lifting. But a police dispatcher told Chase that the fog remained thick over Base Camp and the helicopter there was still socked in.

At 7:45 a.m. Chase finally reached Lagacé at Barnoin Camp. If Base Camp couldn’t get to them, maybe Lagacé could. But the fog was thick there too, he said. There was no way he could fly.

At 8:10 a.m., Chase was shocked to hear yet another new voice on the police line. The man had no idea who Chase was, why she was calling or what had happened.

The new dispatcher explained that Chase’s earlier calls had been forwarded to the police department’s after-business-hours line about 950 miles away in St. John’s, Newfoundland, where the staff was unfamiliar with the Torngats and unaware of just how remote their location was. Now that it was after 8 a.m., Chase was talking with the police dispatcher in Nain, just 200 miles away and the natural place to respond.

It had been nearly five hours since the bear had pulled Dyer from his tent. For five hours they’d been listening to his raspy voice and labored breathing. Five hours without a rescue. And they were starting over now?

Rather than tell her story again, Chase tracked down the last dispatcher she’d worked with in St. John’s. When she reached him, he had good news: The sky over Base Camp had cleared and a helicopter was on its way with a medic and a bear guard on board.

Minutes later, the group heard the thump-thump-thump of the chopper’s blades and saw it moving through the mountains and across the fjord toward them.

From inside the tent, Dyer heard someone shout, “Here comes the helicopter!”

Outside, the others waved their arms and jumped up and down, signaling for it to land.

Brandridge, a former cop with broad shoulders and a stocky frame, got off the helicopter and huddled with Isenberg to get an update on Dyer’s status.

Brandridge ducked into the cook tent and found Dyer conscious and checkered with bloody bandages. He had a laceration over one eye and the lower part of his left earlobe was gone. But all things considered, Brandridge was pleasantly surprised. “I was expecting chunks of meat missing, more puncture wounds,” he said later.

When Brandridge told Dyer that they were going to fly him out, Dyer’s eyes brightened. “Good!” he rasped.

Brandridge maneuvered Dyer onto a scoop stretcher—a clam shell-like contraption that can open up and be placed around a patient—and with the other men put the stretcher on a backboard. Chase held onto Dyer’s hand as they carried him to the helicopter.

As the helicopter rose through the clouds, the people they left behind became tiny specks and then disappeared entirely.

Isenberg looked out the window, counting polar bears and black bears along the way.

Back on the ground, Merkuratsuk began gathering wood and building a fire, his gun slung over his shoulder. The level of fear in the camp dropped a few notches. A fishing boat was on its way from Base Camp. If the weather cooperated, they should be safe on board by late afternoon.

The idea of spending another night on the fjord was too terrifying to contemplate, particularly when Merkuratsuk told them what he had seen before the helicopter landed: a large polar bear walking in the area where the group had planned to hike that day.

Jacko Merkuratsuk knew Nachvak Fjord—and polar bears—as well as anyone in the region. When he and his nine siblings were growing up in Nain, they spent most of their summers at the fjord. One of his brothers had been born there.

Three of his siblings, as well as his son, were bear guards, licensed by Parks Canada to travel into the park as guides.

It was Jacko Merkuratsuk and other local Inuits who had helped inspire the population study of the Davis Strait polar bears that biologist Elizabeth Peacock had launched in 2005. They seemed to be seeing more polar bears in the region, and if they were right, they wanted Parks Canada to raise the annual quota for polar bear hunting. At that point, the five Inuit communities in Nunatsiavut could kill a total of six bears a year, a quota that had been in place since 2001.

The hunting licenses are distributed via a first-come, first-served system to members of Nunatsiavut’s native communities. Hunters are given 72 hours to try to kill a bear before they have to return the license so it can be passed along to someone else. Once the quota is met—six bears in the past, or 12 bears now in 2014—the season ends. Different quotas are set for the other regions of Canada where polar bears are hunted.

Though this system is controversial outside native communities, it allows for the continuation of a traditional way of life that assigns special cultural capital to polar bears. Killing a bear can also result in a financial windfall. Good-paying jobs can be hard to come by in these remote areas, and raw hides go for $8,000-$10,000 on international markets, and have sold for as much as $22,000. The meat of the bear is eaten, too.

Elders in native communities are a valuable resource for researchers trying to understand the implications of climate change for the region and for the bears.

In 2010 Moshi Kotierk, a social science researcher with the Department of Environment in the government of Nunavut, questioned 31 Davis Strait hunters and elders about polar bears and climate change.

Twenty-four reported seeing more bears and agreed with the statements: “There are problem polar bears now.” “To sleep in tents is concerning. I won’t sleep in tents any longer.” “They are in or around communities.” Eleven didn’t remember seeing polar bears in the Davis Strait in the 1940s, ’50s or ’60s.

Few connected the increase in bear-sightings with climate change, but the majority agreed that the sea ice has changed significantly.

Twenty reported that the ice doesn’t form as well as it used to, agreeing with the statement that “ice that we use[d] to travel over, we can’t.” Eight believed the loss of ice had led to an increase in the number of bears.

In Labrador, unpredictable ice can have deadly repercussions. Residents of Nain and other communities around the Torngats rely on snowmobiles—they call them Ski-Doos, after the company that makes them—to get around in the winter. The Ski-Doos are their cars; the ice is their highway.

But the ice that once provided sturdy, safe passage is no longer fully trustworthy. A key element of climate change is variability—not only is the climate changing on a grand scale, over years and decades, but it’s also changing on an immediate scale, with higher highs and lower lows. In addition to freezing later and melting earlier, the ice now varies during the season.

In Nain, locals say a Ski-Doo can be flying across ice that appears normal when suddenly the ice cracks and the sled crashes through to the frigid ocean below.

Although the Merkuratsuks rarely mention climate change directly, their familiarity with the ecosystem allows them to identify the shifting line that separates safe and dangerous travel in the Torngats. Particularly when it comes to polar bears.

While Gross and Chase knew from their research that bear guards carry guns to protect groups from attacks, they didn’t know that bear guards can also determine whether a bear has been in the area recently. The Merkuratsuks know which areas along the fjord polar bears are drawn to, and which should be avoided. They know not to walk in the willows—an area that some of the Sierra Club hikers used for their bathroom—because polar bears go there to keep cool from the summer sun.

They also know the routes that polar bears walk, including the route that Chase and Gross’s group was planning to take—a path called a “polar bear highway” by one Parks Canada official.

And when the Merkuratsuks do encounter a bear—say, one that’s been lounging on a nearby ledge for hours—they recognize it as a sign of danger. They know it’s time to pack up camp and move on.

But Chase and Gross didn’t know what the bear guards knew. None of their research, including their talks with Parks Canada, indicated just how valuable a bear guard could be. And in this case, what they didn’t know nearly killed them.

The helicopter touched down on the landing pad at Base Camp around 8:30 a.m. As the propellers slowed to a halt, an ATV with a trailer pulled up. Dyer’s stretcher was loaded onto a mattress in the trailer and driven to the medic tent.

With Isenberg at his side, Brandridge inventoried and cleaned Dyer’s wounds. He began with the bite and claw marks on his face, which were dripping blood into Dyer’s eyes. After removing each bandage, Brandridge cleaned away the blood and photographed the wound.

“How are you feeling?” Brandridge asked.

“Like shit,” Dyer said.

“That’s not bad for someone who just got attacked by a polar bear.”

After finishing with Dyer’s face, Brandridge peeled off the bandage covering the big wound on his neck.

The thick odor of meat immediately filled the tent—an odor that, to Brandridge, smelled like death.

He saw that the hole in Dyer’s neck was about the width of a pencil and went behind his jugular and toward his esophagus. Each time Dyer inhaled, he was wicking blood into the wound.

Trying to keep his voice calm, Brandridge asked Isenberg to watch Dyer. Then the medic rushed to the main office of Base Camp.

The plan to wait for a medevac plane from Goose Bay, Labrador, wasn’t going to work, Brandridge told Baike and Broomfield. Based on his assessment, Dyer’s condition wasn’t stable after all. His lungs could be filling with blood as they spoke.

Brandridge could clean him up and make him comfortable, but he didn’t have the medical equipment or expertise for the kind of operation Dyer needed to save his life.

After considering their limited options, they decided to put Dyer back on the helicopter and send him to George River, a town about 45 minutes away, where a first-response team with more sophisticated equipment would meet them. From there he’d be flown to Kuujjuaq and then on to Montreal.

Within about a half hour, the helicopter was up in the air, weaving through the passes between Base Camp and the river valley en route to George River. The weather was relentless, with snow in one pass, and sleet and rain in others.

Brandridge radioed Base Camp to say they were making progress. But he couldn’t help but feel that it was unlikely Dyer would survive.

As the helicopter reached the Korrack River Valley, the weather improved. They followed the river to George River, where an ambulance met them at an airstrip.

At about 4:40 p.m., 13 hours after the polar bear had attacked the Sierra Club hikers, The Robert Bradford, a vision in green and white, dropped anchor in Nachvak Fjord.

The fishing boat’s owners, brothers Chesley and Joe Webb, welcomed the five remaining hikers and Jacko Merkuratsuk aboard. Beside them was Cappuccino—called Chino—a fluffy white dog that looked as if it belonged in a suburban home, not on a Labrador fishing boat.

The fog was thick and the rain was cold. Most of the group huddled in the cabin, at a small kitchen table with bench seats. At the front of the cabin Chesley Webb sat at the captain’s wheel and steered the boat through the nasty weather and toward the mouth of the fjord. Frankel stood beside him, looking straight ahead and trying not to succumb to seasickness.

Joe Webb wore thigh-high black waders and a long green rain jacket as he worked on the deck. Two long lines with anchors hanging off of them—called “birds”—dangled from the sides, helping steady the boat in the choppy water. Still, the boat rocked, turning the stomachs of the group and making them generally miserable.

At 7:30 p.m., they neared the mouth of the fjord. But instead of entering the open waters of the Labrador Sea, the Webbs dropped anchor. With little to no visibility and icebergs dotting the coastline, it wasn’t safe to continue in the dark.

Though the Webbs no longer use their boat for commercial fishing, the white-haired, blue-eyed brothers are born fishermen. They eat what they catch or hunt—black duck, ring seal, fowl, Arctic char. That night, freshly caught Arctic char was on the menu, “the most delicious char you’d ever have,” Rodman said.

They tucked in where they could for the night. Frankel and Chase slept in the small, angled bunks below deck. Rodman, Castañeda-Mendez and Gross lay on the floor of the galley, fitting themselves into the small space carefully, like puzzle pieces. Eventually, Castañeda-Mendez was so uncomfortable that he gave up and moved to the galley table. He sat on the bench and laid his head on the table. Gross joined him there later.

They covered themselves with whatever sleeping bags they could find, as wind from the deck found its way through the door into the cabin.

Toward morning the Webbs pulled up anchor and The Robert Bradford steamed into the Labrador Sea. At 5 p.m. after a long day of high waves and bad weather they pulled into Saglek Bay with Base Camp in sight.

That night, their most basic needs were met: A warm meal. Showers. Cabin-like tents to sleep in. All behind the formidable bear fence that surrounded the camp. They felt safe.

The next day, while they waited for the plane that would take them to Kuujjuaq, they set off for one last hike, this time flanked by two bear guards. The climb up Base Camp Mountain was a short but steep ascent through snowy passes and into clear, bright skies. At the top, one by one they used rocks to form a makeshift Inukshuk, a statue of stones traditionally used in native Arctic communities to communicate something—an indicator of safe passage, the location of a path or a marker for a reserve of food.

Inukshuks can also have a spiritual purpose, sometimes used as a monument or memorial to an event or person.

The wind blew back the brims of their hats as they piled their rocks high. Below them, they could see Base Camp safe within its fence. Just to the north, they could see the snow-crested mountains of Torngat Mountains National Park.

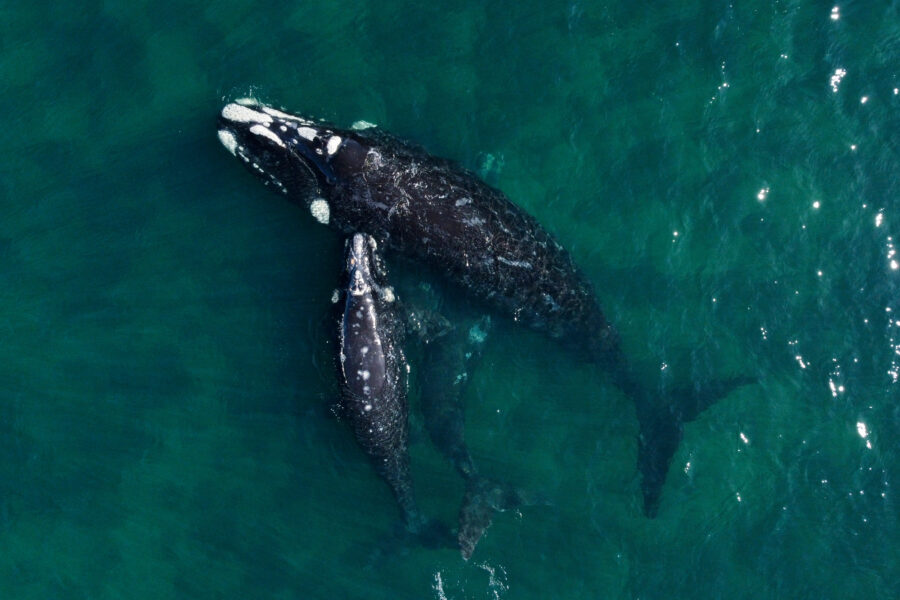

Decades of studies about polar bears and the rapidly changing climate have led to a prevailing scientific narrative about the bears’ future: the loss of sea ice, driven by man-made climate change, will eventually force them ashore for such long periods of time that the species is inevitably doomed.

In recent years, however, a competing narrative has emerged, driven in large part by the work of Robert “Rocky” Rockwell, a biologist and ecologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Rockwell has studied various species in the lowlands of the western Hudson Bay for 46 years, and in 2009 he began publishing his findings about polar bears and their eating habits. He suggests that because they bears are “opportunistic eaters,” they might be able to survive climate change by foraging for food during their extended periods on land. His work has captured headlines in major media, because it runs counter to previous reports about polar bears. It has also been adopted by climate change skeptics as proof that the bears aren’t threatened by climate change, although Rockwell himself doesn’t draw that conclusion.

Rockwell writes that the western Hudson Bay bears don’t necessarily fast during their months off the ice, when their hunting skills are thought to be almost useless. Some gorge on snow goose eggs and even the geese themselves. They also eat berries and plants.

Rockwell points out that while a polar bear can’t run down a caribou, he has seen bears wait for a herd to pass by and pounce on stragglers. He also has seen bears stalk sleeping seals on land. Locals in the Torngats report similar incidents, as well as occasional sightings of polar bears catching char in streams, much as their grizzly ancestors fished for salmon.

“I find it a little bit crazy that people say ‘No, no, the polar bears only eat seals on the ice and when the ice goes the polar bears will have less to eat,’” Rockwell said in an interview. “Well, they’ll have less seal to eat, but they’ll opportunistically eat other stuff.”

Rockwell’s critics say polar bears have long been known to find alternative food sources while they’re ashore. They also say that the group’s Hudson Bay studies focus on such small sample sizes—in a few cases just 10 bears—that the data can’t be extrapolated to predict how polar bears are responding to climate change globally.

Perhaps the biggest flaw they see in his work is the idea that terrestrial eating—eating on the land while off the ice—is helping bears in the western Hudson Bay. In addition to having decreased body condition and lower reproduction rates, the bear population there has declined by 22 percent since the early 1980s as the ice has broken up earlier.

“If terrestrial feeding was the savior for polar bears, why are polar bears starving on land during the ice-free period?” asked Derocher, the biologist who has studied polar bears for more than 30 years.

One way to understand what may happen to bears in the future, Derocher says, is to understand what happened to them in the past.

Ten thousand years ago, polar bears lived in the Baltic Sea, around Sweden, Denmark and near Finland. As the climate warmed, there wasn’t enough ice there to sustain their population, so they followed the ice north.

“They didn’t hang around to try to exploit terrestrial resources,” Derocher says. “This is a sea ice-obligate species and once the sea ice dropped below that threshold, that just didn’t give them enough access to prey.”

The big question, of course, is whether polar bears can adapt to the latest changes in their habitat.

Brendan Kelly, former deputy director for Arctic science at the National Science Foundation, looks at this question in the context of the pace of change. A species’ ability to evolve in the face of new conditions depends in large part on the length of its life span, he explains. If the habitat changes slowly and multiple generations can survive during that period, traits that prepare the species to thrive in the new habitat will flourish while other traits gradually disappear.

But when a species with a long life span, like polar bears, is confronted with a rapidly changing environment like the melting of the Arctic, adaptation is less likely.

Polar bears in the wild live an average of 15 to 18 years, with some living into their 30s. That means that a 15-year-old bear, living right now on the Davis Strait, has already seen its ice-free season extended by approximately two weeks. The spring melt comes about a week earlier than when the bear was born and the freeze-up comes about a week later.

“When environments change really abruptly, more typical than adaptation, which takes just incredible luck, is extinction,” Kelly says. “I’m in the camp that would argue that we’re really flirting with danger here because we are changing the sea ice environment. We’re radically changing it, in just a few generations of bears.”

The loss of sea ice, and its implications for polar bears and other large mammals that depend on the ice, Kelly says, is less like the evolution of plants over millennia and more like the abrupt environmental changes caused by the arrival of a meteor.

“We can’t tell you what the outcome will be,” he said. “All we can say is the prudent decision would be to try to slow this down.”

Next: Chapter 10

Go back to Chapter 8 | Meltdown Homepage

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,