Judith Enck has spent her entire career working to protect public health and the environment.

Enck took the helm of New York’s oldest environmental organization, Environmental Advocates NY, soon after graduating college, then went on to hold senior leadership roles in state and federal government, including as deputy secretary for the environment in the New York Governor’s Office and a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regional administrator during Barack Obama’s two terms. Now, as a professor at Bennington College and president of the Vermont-based nonprofit Beyond Plastics, Enck is on a mission to “end plastic pollution everywhere.”

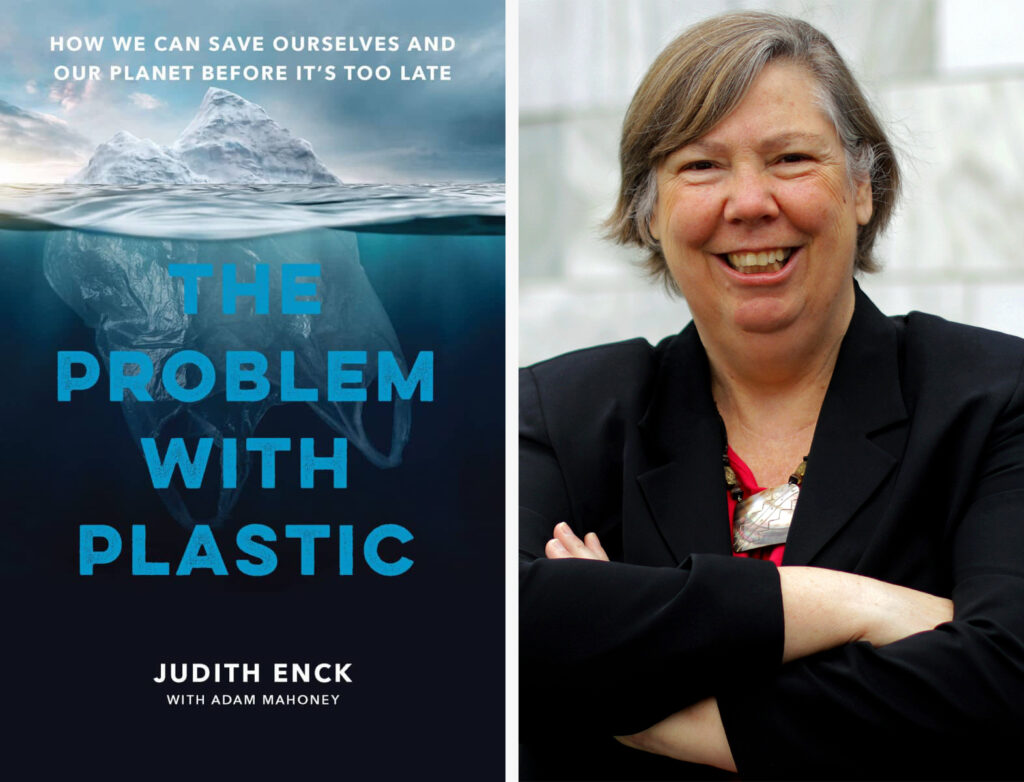

Toward that end, Enck, who describes herself as a “solid waste gal,” wrote a new book with journalist Adam Mahoney called “The Problem With Plastic.”

The main problem with plastic, the authors say, is that it’s ubiquitous, polluting the planet, driving climate change and making us sick.

Plastic production has increased exponentially, from about 2 million tons a year in 1950 to 450 million tons a year today, with no limit in sight. And because plastics are made from fossil fuels and thousands of toxic chemicals derived from oil and gas, they cause harm throughout their life cycle, from extraction of the fossil fuels they’re made of to their production, use and disposal. Low-income communities and people of color who live near plastic plants bear the brunt of the industry’s toxic emissions, Enck and Mahoney say. Yet we all inhale and consume hundreds of thousands of microplastics per year.

Plastics have become so pervasive that scientists have found them blowing in the wind, near the peak of Mt. Everest, in the snow of Antarctica, in the ocean’s deepest trenches, in placentas, breast milk, stool, blood, lungs and even in our brains.

Plastic was never designed to be recycled, Enck explains in the book. The only aspect of plastics actually being recycled is the myth that recycling will stop plastic pollution. Inside Climate News recently spoke with Enck about the extent of the plastic crisis, its role in the climate crisis and what it will take to move beyond plastic. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

LIZA GROSS: Was there a specific moment or event that made you decide that plastic pollution was the issue you wanted to devote your time and energy to?

JUDITH ENCK: Well, there are two moments. One is the moment I was born. My parents, the late Helen and Sonny Enck, named me after St. Jude, the patron saint of lost causes. But I don’t believe plastics is a lost cause. I just think it’s an uphill battle.

But seriously, I do remember a moment, though it’s not like I wasn’t following the issue.

I was sitting at my desk at EPA Region 2 in lower Manhattan, and I read an article about the massive amount of plastic loading into the ocean, and it stopped me in my tracks. I know how important the ocean is, a major source of protein for most of the world. And I read that about 80 percent of plastic in the ocean comes from the land. It’s roadside litter that goes down a storm drain, into a stream, into a river, into the ocean. Or it’s derelict fishing gear. And it is really damaging the ocean.

And I decided at that moment, when I left the EPA, I was going to work on plastics. I didn’t know how, I didn’t know where, but that’s what led to the launching of Beyond Plastics, and then eventually the writing of this book.

GROSS: People often talk about plastics breaking down, but I’ve heard you say that’s not the right way to think about it. Could you expand on that?

ENCK: Plastics are made from fossil fuels and chemicals, and they are not degradable. So they don’t break down, they become smaller pieces of plastic. And in many ways, those smaller pieces are a much greater risk. So five millimeters or less is a microplastic, the size of a grain of salt. And then even smaller than that is a nanoplastic, and that’s what we’re breathing in and swallowing and, and that’s what’s building up from the Himalayan Mountains to the bottom of the Mariana Trench and everything in between.

GROSS: One thing that people might be surprised to learn is that plastic recycling was actually a PR strategy. In the book, you say that’s been part of a strategy to shift responsibility from the producer onto the individual consumer, to obscure the fact that companies are producing huge volumes of materials that can’t be recycled. How did that strategy become so effective?

ENCK: Because we were all subjected to a multimillion-dollar advertising campaign by plastic companies deceiving us into thinking we can recycle most of our plastic, which just isn’t true. You can recycle an old aluminum can into a new can, newspaper into cardboard or other paper products. But with plastics, we’ve got 16,000 different chemicals, many different colors, many different plastic types, or polymers. Think of your own home. You may have a bright orange plastic soap detergent near your washing machine and a black plastic takeout container in your refrigerator and a plastic bag on your counter. None of them can be recycled together. You have to separate everything by color, by chemical and by polymer. The people who know this the best there are plastic manufacturers, and yet they chose to spend millions of dollars telling us, don’t worry about all of your single-use plastic packaging, for instance, just put it in your recycling bin. But it really messes up recycling programs.

So I want to be clear: People should keep recycling paper, cardboard, metal and glass, and compost your yard waste and your food waste. But plastic recycling has been an abysmal failure.

GROSS: I was surprised to learn that the industry intentionally created confusion around recycling symbols, conflating the chasing arrows symbol that indicates products were made out of recycled materials with the numbers used to indicate things that can be recycled. It’s amazing how those very simple symbols could be such a powerful tool of misinformation.

ENCK: Yes. On one hand, it’s great that people look for the symbol because they want to do their part. But it is a huge problem when it’s used deceptively. The [Federal Trade Commission] has a voluntary guide that tells you when you can and cannot say that something is recyclable and when you should and shouldn’t use the symbol. But it’s voluntary, so most of the companies ignore that.

And you know, when pressed, I do say keep recycling number one and number two plastic. You have a little bit of a fighting chance that they will get recycled. Most of the other plastic either gets littered in the environment or goes to landfills or to incinerators. And what’s really troubling is, unless plastic is burned at a garbage incinerator, which is fraught with air pollution and other pollution problems, every single piece of plastic ever created is still on the earth today.

GROSS: Even if we were able to recycle things, with all the chemicals that are in these plastics, wouldn’t recycling just be concentrating the chemicals? Do we need to worry about that with the items that actually can be recycled, the ones and twos, as well?

ENCK: A lot of these 16,000 chemicals are very toxic. We’re talking about PFAS chemicals, lead, mercury, cadmium, vinyl chloride, things that should not be touching our food. Beyond Plastics does not believe that recycled plastic should be used in any food packaging. We don’t want food or beverage packaging made from recycled plastic.

We’ve looked a little bit at the Food and Drug Administration process for companies to get approval to use recycled plastic in their consumer products. And the nicest thing I can say about it is it’s a very flimsy process itself. It’s self-reporting, and the FDA seems to have a giant rubber stamp out. They’re not looking out for our health and our well-being when they allow recycled-content plastic for food packaging.

GROSS: Speaking of all these toxic chemicals in plastics, scientists have been linking plastics increasingly to all sorts of non-communicable diseases. What are they learning about potential mechanisms of harm in what seems to be a relatively new yet ballooning research field?

ENCK: It is new, which is why the cuts in federal funding for public health research is so concerning. The first really comprehensive study I looked at was the presence of microplastics in the human placenta, which was done by Dr. Ragusa in Rome with some other Italian scientists. The baby is only in utero for seven, eight, nine months and is already being born pre-polluted, and there’s also microplastics in breast milk.

Microplastics have been found in virtually every part of the human body that scientists have looked at. We either inhale them or we swallow them, and microplastics have been found in our blood, our kidneys, our lungs, male testicles.

I think two of the most significant studies are one that was published by New England Journal of Medicine, looking at microplastics in the heart arteries, and they looked at plaque, and found if you had microplastics on the plaque, which many of the patients did, you had an increased risk of heart attack, stroke and premature death. And then another recent study looking at microplastics in the brain unfortunately documented that the microplastics, nanoplastics, cross the blood-brain barrier and increase risk of Alzheimer’s and other neurological diseases.

And recently there have been a couple articles about people asking, can you get it out of your body? It’s not like lead and chelation. You know, there’s no easy way to get this out of your body. So let’s redouble our efforts to prevent it from going into our bodies.

GROSS: What is the best way for people to keep this stuff out of our bodies?

ENCK: You can’t shop your way out of this problem. There are some steps you can take. The book has a section for people to do a home audit. Look at your kitchen. Get rid of that plastic cutting board. Do not put plastic in the microwave. Only buy cotton bed sheets because you’re spending, on a good day, seven hours in bed, so make sure your sheets and blankets are not made of plastic.

I know a lot of people who tell me the great lengths they go to avoid plastic, and if I’m close friends with them, I say, “That’s really good—could you spend half of that time calling your legislator and writing a letter to the editor?” We have to get systemic change. We have to mainstream alternatives to plastics.

Now here’s the good news: A lot of the alternatives are already here. Give me old-fashioned paper, cardboard, metal, glass, because it can be made from recycled material, and actually does get recycled. But I want to emphasize, by far the most important thing is reduction, reuse and refill. Building that refill-reuse infrastructure is crucial.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowGROSS: There’s a lot of talk about stopping plastic pollution at its source. So just cap the production. More than 100 countries during the recent U.N. plastics treaty talks pushed for that to no avail. What do you think some of the most promising strategies are to really get a handle on this crisis?

ENCK: I think the action is at the state and local level. There are a lot of people—and we wrote the book for these very people who want to do something about the plastic crisis—and they can show up at their city council and say, “Let’s ban plastic bags.” They can show up at their county legislature and say, “Let’s provide funding to Meals on Wheels and restaurants to install dishwashing equipment so we’re not all eating our delicious food off of, you know, polystyrene plastic plates and forks.”

The way we’re going to win is with probably 1,000 different strategies, with tens of thousands of different people in the lead. This issue really calls out for local action.

And then you climb the ladder. In New York, for instance, New York City banned plastic bags, and then the state did. That one little thing of banning all plastic bags at retail stores has been immense, and it’s just one of many things that can happen.

“The way we’re going to win is with probably 1,000 different strategies, with tens of thousands of different people in the lead. This issue really calls out for local action.”

GROSS: There was a pretty striking stat in the book about plastic production emitting four times more greenhouse gases than the global aviation industry, which we think of as a massive contributor to the climate crisis. Why do you think the connection between climate and plastic is still unappreciated?

ENCK: Climate change has been front and center for a long time, and it is an overwhelming problem. Then you layer on plastics as a climate issue—it’s just a lot. But it’s actually not hard to document. Back in 2001 I wanted to figure out, because no one else had done it, what are the greenhouse gas emissions over the plastic life cycle?

We commissioned a report to look at greenhouse gas emissions from production, use and disposal, and what we found was pretty disturbing. We found that 232 million tons of greenhouse gases were emitted every year. That’s the equivalent of 116 coal-fired power plants. So we did this report, The New Coal: Plastics and Climate Change.

Beyond Plastics and the Center for International Environmental Law both identified plastics as a major climate issue. I just think the climate crisis is overwhelming, and people think about power production and transportation.

Now here’s the great irony: fossil fuel companies know they’re losing market share for transportation and power production. So their plan B is plastic production. The largest plastic producer in the U.S. today is ExxonMobil.

GROSS: You dedicated the book to the low-income communities of color living in the shadow of plastics facilities in the Gulf Coast and beyond. Are there any stories you heard from people living near these plants that really stuck with you?

ECNK: I was in Port Arthur, Texas, a couple years ago, and looking at this enormous petrochemical buildout, with local residents dependent upon the jobs, dependent upon this industry to keep Port Arthur alive, and yet Port Arthur is not doing well. I toured the Houston Ship Channel with a representative from Houston Air Alliance, and saw how close people’s homes are to these facilities. Same thing in Cancer Alley in Louisiana.

Our government has allowed the creation of sacrifice zones, and that is unethical. If people had resources, a lot of them would move. But they don’t have financial resources, nor should they move. These are their ancestral homes.

You hear Jo and Joy Banner with the Descendants Project talking about how we went from plantations to chemical plants. The through line is racism. So it means a lot to have, for instance, Dr. Robert Bullard endorse the book and the others, mostly women, happy to be profiled. They’re just doing extraordinary work, facing enormous odds, but they’re also winning.

Gross: Is there a final hopeful message you’d like to share?

ENCK: We wanted the book to be hopeful, which is hard to do on this issue. But we are hopeful, because while I don’t live in Cancer Alley or the Houston Ship Channel, I can work on policies to reduce the demand for plastics. That’s why we wrote the book. You can’t just leave it to people living in Cancer Alley to solve the problem.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,