Inside the Marine Mammal Care Center in Los Angeles, more than 80 sea lions and seals lounge lethargically in outdoor fenced-in pens or paddle in small pools. Some bark and moan. Many of the sea lions noticeably stare into space or crane their necks so that their whiskers point to the sky. “Stargazing” is what animal rescuers at the nonprofit call the strange behavior.

That gaze is indicative of domoic acid poisoning, a neurotoxin produced by an algae called Pseudo-nitzschia, which attacks the nervous systems of marine life. In the last few months, scientists said hundreds of sea lions, dolphins and seabirds have fallen ill or died after consuming sardines or anchovies that have feasted on an algal bloom along the California coast since winter. The biotoxin accumulates in the feeder fish.

Two cases of whales dying from domoic acid toxicosis have been confirmed by nonprofits authorized by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to test dead marine mammals. Last week, the Pacific Marine Mammal Center in Laguna Beach and the Ocean Animal Response and Research Alliance in Dana Point linked the algae to a humpback that washed ashore at Huntington Beach in January and a minke whale found dead on Long Beach in April.

“It’s a massive event,” said Dave Bader, chief operations and education officer at the marine mammal center in Los Angeles who last week provided a virtual tour of the sickened animals to Inside Climate News. Since February, the center has cared for more than 300 poisoned animals—more than the organization typically sees on an annual basis.

“We’ve exceeded our budget for hospital supplies and food,” said Bader, a marine biologist.

Scientists and conservation groups said the algal bloom shows no sign of retreat and the upheaval has heightened vigilance about its potential to harm, or limit, the human food chain.

“These marine mammals are sentinels for us. They’re like the canary in the coal mine,” said Kathi Lefebvre, a research biologist who was the first to detect domoic acid in sea lions in 1998 and now oversees the Wildlife Algal-Toxin Research and Response Network for the U.S. West Coast (WARRN-West) at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, Washington.

“The ocean ecosystem is full of toxins right now,” Lefebvre said.

Domoic acid also causes amnesic shellfish poisoning, which can be lethal to humans who consume contaminated seafood. Fortunately, most commercial seafood that people consume is tested for toxins regularly to ensure this doesn’t happen, Lefebvre said. “That’s the only reason we don’t have these massive human die offs.”

This is the fourth year in a row that California has experienced such a harmful algal bloom. “Warmer waters are causing these blooms to be bigger and more damaging than they have been, entering into new areas, going further and contaminating the food web for longer,” Lefebvre said.

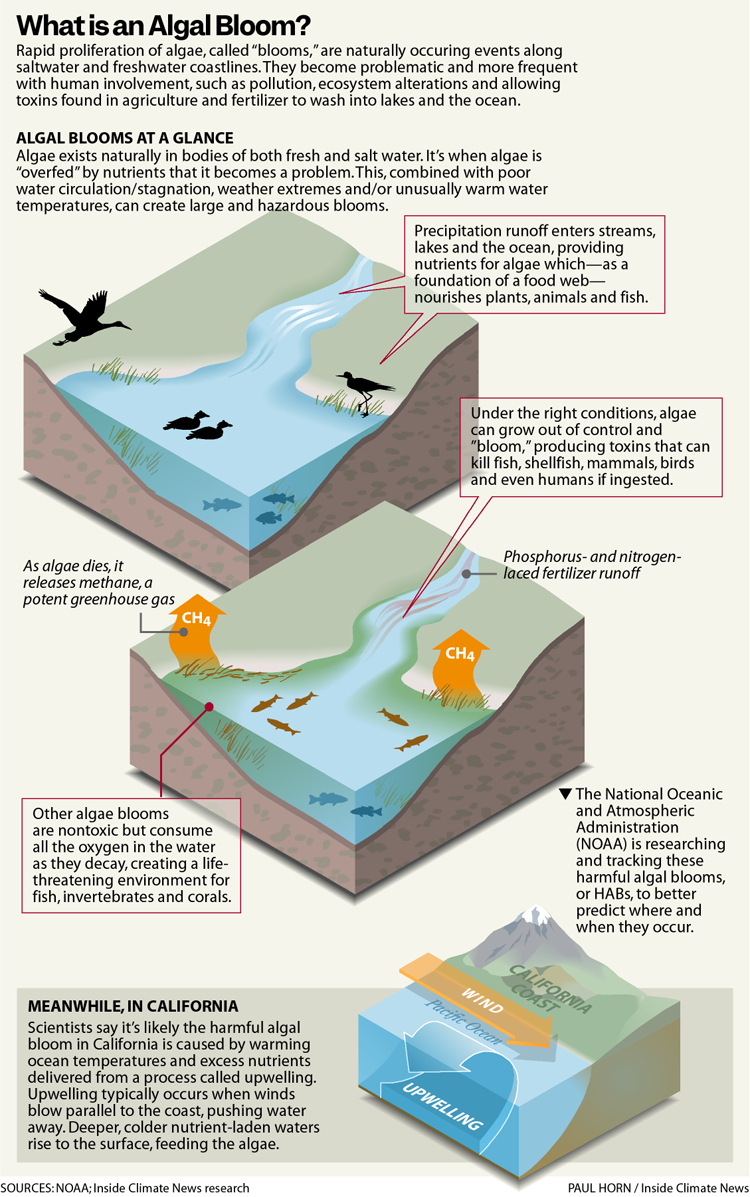

The warmer waters accelerate algae growth. It is further fueled by nutrients that rise to the surface from deeper colder waters as winds blow parallel to the coast in a process called upwelling.

These events typically occur in spring and summer, but this year is an anomaly.

“It started earlier than normal, and it’s lasting longer than normal,” said Justin Viezbicke, who coordinates responses to marine mammal strandings in California for NOAA Fisheries. “I’m guessing, when we’re all said and done, this will be, if not the largest, one of the largest domoic acid events we’ve had here.”

Tracking the Stranded

Viezbicke speaks weekly with more than a dozen animal rescue and rehabilitation groups that comprise NOAA’s West Coast Marine Mammal Stranding Network to share data and resources about the situation.The first reports of animal strandings in California that were linked to domoic acid poisoning emerged in late February.

But the algal bloom likely began as early as December in Baja California in Mexico before spreading north, according to Clarissa Anderson, an oceanographer and director of the Southern California Coastal Observing System. SCCOOS monitors ocean health and changes from its base at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

Anderson developed the California Harmful Algae Risk Mapping (C-HARM) system, which uses satellite remote-sensing data and statistical models to forecast domoic acid events. But that month, with holidays, “we just weren’t paying attention,” she said.

When Anderson reviewed the model’s data months later, after a colleague from Mexico mentioned reports of marine mammal strandings in December, she saw there was a spike in Pseudo-nitzschia around Christmas near the Ellen Browning Scripps Memorial Pier in San Diego. “We saw that model turn hot in December,” Anderson said. “And by hot I mean toxic.”

Since then, she said the bloom has surged in locations up and down California. By late February, the number of disoriented or sickened marine life were noticeably rising, she said. “And they haven’t stopped since.”

Every day citizens and lifeguards are phoning the marine mammal hospital in Los Angeles and other members of the west coast stranding network with sightings of distressed animals on Manhattan, Hermosa, Redondo and other popular beaches from San Diego to Monterey Bay.

Sea lions foaming at the mouth. Pelicans with tics and tremors. Dolphins lapping in the waves. “They’re having seizures right there in the shoreline,” said Bader from the hospital.

Unlike sea lions, which instinctively come to shore when they are sick, dolphins remain sick at sea. “When they are so sick that they end up on the shore, they’re very close to death,” Bader said. “They have a heart attack and die.” If they don’t, he said, the most humane act is euthanasia.

In cases where animals are dead, another call is made to the Ocean Animal Response and Research Alliance, an organization that specializes in post-mortem exams.

Learning From the Dead

The alliance’s founder, Keith Matassa, last week performed a dozen necropsies in a single day, something he said he had not experienced before.“We never had a day of 12 animals, and we’re only at 3:30 in the afternoon, which means that the afternoon rush hasn’t even started yet,” he said. Most were common dolphins, known for their acrobatic and playful behavior in the open sea when they are healthy.

The next day, Matassa allowed Inside Climate News to observe part of an examination he was conducting on El Segundo beach via video call.

“On a necropsy, you get to know that animal from tip of the tail to the tip of the dome. You open that animal completely up, and you see everything,” said Matassa, who has worked in marine mammal rescue and rehabilitation for 40 years.

He aimed his camera phone towards the beach where a 7-foot, 234-pound black and gray common dolphin lay on its side in the sand, its stomach cut open. Then he showed the hatchback of a vehicle where his colleague worked on a tray with the animal’s kidney, liver, blubber and spleen. She was extracting small pieces of the organs and tissue and preparing samples to send to a lab, along with urine, feces and stomach contents, which will be tested for domoic acid.

Later that day, Matassa said he was scheduled to examine at least four other animals on Venice and Manhattan beaches.

“Yesterday, when I was in the field, I went to examine one animal, and got there, there were two animals, and no sooner had turned around than a third one was coming in and being dropped off,” he said. “Someone described it as ‘Animal Armageddon.’”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowSamples from deceased animals are sent for analysis at labs, including NOAA’s wildlife algal-toxin research center in Seattle, Washington, that Lefebvre oversees. “We’re doing samples like crazy. We’ve got another, I think 50 samples in the queue right now,” she said.

The center collaborates with the marine mammal stranding network on the West Coast as well as private and public partners to test samples. They check for domoic acid and another potent paralytic shellfish toxin called saxitoxin, which is being detected in some of the same coastal areas as domoic acid.

Rescue to Rehab

Rehabilitation centers are doing their best to help rescued marine life. It’s not easy.

In Los Angeles, the Marine Mammal Care Center relies on 300 volunteers to help with the dozens of sick sea lions and seals. And treatment options are limited. “There’s no miracle cure,” Bader said.

“We’re really feeling the strain, as far as staffing is concerned, and how much effort we’re putting in each day to get those animals recovered,” he added.

The primary approach to ease symptoms is sedation and anti-seizure medicines, according to Rebecca Duerr, the clinical veterinarian and research director at the International Bird Rescue’s two wildlife clinics in California. Its facility, across the street from the Los Angeles marine mammal center, is caring for at least two dozen adult and juvenile brown pelicans. Lately, more of the younger seabirds have been found malnourished.

“We’re getting those super young chicks in care as well, but they do not have domoic acid toxicity. They’re just starving,” Duerr said. She estimates that the birds’ parents were poisoned, leaving the fledglings to fend for themselves.

At the marine mammal center caring for the sick sea lions is a team effort. Volunteers from the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta recently spent their morning in the center’s hospital, mixing a runny gruel of herring, water, vegetable oil, vitamins, and other essential nutrients to tube feed animals too weak to eat.

In a virtual tour, Bader walked past 16 pens where sick animals are held. Some are too ill to swim and are kept in “dry pens,” he said. The animals can receive medical care more easily in these enclosures. As they begin to recover they are moved to pens with small pools.

In one of the dry pens, Bader pointed to several 400 to 600 pound male sea lions. Nearby, he showed another enclosure housing a group of 200 to 300 pound pregnant females, which Bader said would never give birth to live pups.

“Amniotic fluid can be a reservoir for domoic acid. So we want to make sure that they have survival, and that means not not being pregnant anymore,” he said. If the female sea lions don’t miscarry on their own, the hospital typically induces them to terminate the pregnancy.

It can take several weeks to months for animals to recover fully from the poisoning, if they do at all, Bader said. “We’re seeing worse outcomes for our patients than we have in the past,” he added.

One group of sea lions stood out in the care center. Swimming in a small pool, a few sea lions popped up from the water when a staff member entered the pen with a bucket of whole herring. Some even leapt from the pool. As the staffer dumped the herring, a feeding frenzy of dives and underwater somersaults ensued. That’s a good sign, Bader said. They were recovering.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,