Harmful “forever chemicals” flow from wastewater treatment plants into surface water across the U.S., according to a new report by a clean-water advocacy group.

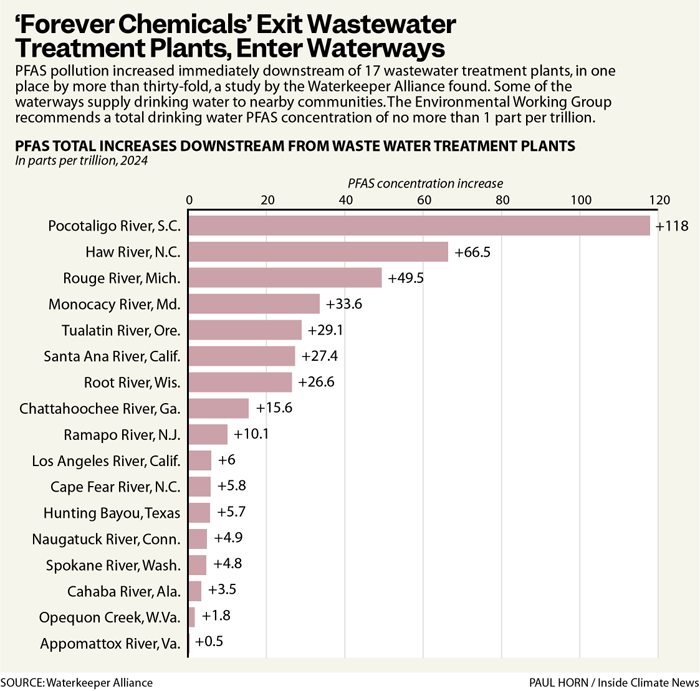

Weekslong sampling by the Waterkeeper Alliance both upstream and downstream of 22 wastewater treatment facilities in 19 states saw total per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) concentrations increase in 95 percent of tested waterways after receiving discharge from the facilities. Some of the waterways supply drinking water to nearby communities.

The study also found increased PFAS levels downstream of 80 percent of waterway-adjacent fields in eight states treated with “biosolids,” solid matter recovered from the sewage treatment process and spread on farmland as fertilizer.

Research on PFAS has linked the chemicals to multiple types of cancer, liver and kidney damage, reduced fertility, lower birth weights and endocrine system interference. Now, scientists suspect the chemicals can also impair immune system function, said toxicologist Linda Birnbaum, former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program, who was not involved in the new report.

The study is the second phase of Waterkeeper Alliance’s National PFAS Monitoring Initiative. Phase 1, conducted in 2022, revealed PFAS contamination in 83 percent of tested U.S. rivers, lakes and streams. That number rose to 98 percent of the sites included in the most recent study.

“PFAS pose one of the most urgent environmental and public health threats of our time,” Waterkeeper Alliance CEO Marc Yaggi said at a press briefing after the report’s release last week. PFAS from industrial sources flow through wastewater treatment plants and into waterways of ecological, cultural, recreational and public health significance, he said.

“These wastewater treatment plants are not designed to remove PFAS, and they face significant challenges managing this pollution, while accountability from industrial source polluters remains limited or nonexistent,” said Yaggi.

PFAS are a class of more than 9,000 man-made compounds designed to resist water, grease, heat and oil. Found in a wide range of consumer products, from clothing and nonstick cookware to cosmetics and fire retardant foam, PFAS are also released as industrial waste by the facilities that manufacture these goods.

Once in the environment, they do not break down, instead accumulating in water, soil and air. That’s how they got their unnerving “forever chemicals” name.

“It really doesn’t matter how you’re exposed to PFAS, whether you eat it, drink it, inhale it or even if some of it gets in through your skin,” Birnbaum said. “They’ll build up in us.”

While advanced treatment technology to remove PFAS from wastewater exists, most facilities do not have it. None of the 22 facilities included in the study employed PFAS removal technology, the Waterkeeper Alliance said.

The report’s findings underscore the need for stricter limits on PFAS discharges from industry sources, said Kelly Hunter Foster, the alliance’s senior attorney. Absent federal standards, restrictions on PFAS discharge are left to state or municipal authorities, she said.

The lack of Environmental Protection Agency guidance places an unfair burden on cities that lack both the technology to remove PFAS from treated water and the expertise to determine the acceptable level of any given chemical, said Hunter Foster.

The result is a regulatory free-for-all. All but one of the treatment facilities analyzed in the study process water from industrial users that have no restrictions on the concentration of PFAS in their wastewater.

In 2024, the EPA under the Biden administration set its first nationwide, enforceable limits on six PFAS compounds in drinking water.

Countless more PFAS chemicals may be harmful to humans and wildlife alike. “I don’t know that any of these chemicals are completely non-toxic,” said Birnbaum, the former federal toxicologist. PFAS left out of EPA regulation are less understood, not necessarily less dangerous, she added: “If you don’t look, you don’t know.”

And the new EPA rules are now slated to be pared back. The Trump administration said in May that it plans to delay enforcement of two of the Biden-era PFAS limits while rescinding the other four.

The Waterkeeper Alliance study identified as many as 14 different PFAS types at elevated levels in a single sampling site, and a total of 19 at elevated levels across the locations. Several of the compounds most commonly found at elevated levels downstream of treatment facilities in the study are not among those with EPA drinking water limits.

Currently, the EPA does not have any PFAS effluent limits or pretreatment standards, regulations that would restrain the ability of industry sources to discharge PFAS in the wastewater they send to treatment facilities.

“The lack of federal standards makes it impossible to keep the PFAS out of the system,” said Hunter Foster.

The new report includes policy recommendations calling for nationwide regulation of PFAS that treats the chemicals as a class, rather than individual substances, and the eventual phasing out of PFAS production and use.

A complete reduction in PFAS production is critical, Birnbaum argued. “Turn off the tap,” she said. “We’ve got to stop making these things.”

Clarification: This story was updated July 2, 2025, to clarify that the study focused on locations in 19 states, rather than that all states had elevated levels of PFAS; 18 of them did. Additionally, the story was updated to clarify that the 14 types of PFAS found at one site and 19 found across locations were those at elevated levels, rather than the total variety found.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,