Kevin Miller can get a person to the brink of heat stroke in 30 minutes.

In a chamber with a temperature of around 100 degrees, he starts them out on the treadmill, switching off between three minutes of walking and two minutes at an all-out sprint. Soon, they’re breathing faster, their blood vessels are dilating and their heart is working overtime to pump much more blood than usual through their body, fighting to get oxygen to their muscles and organs.

In Miller’s lab, these participants are safe: He brings them close to the heat-stroke threshold of a 105-degree core body temperature in the name of science, to test the efficacy of different treatments.

Heat is the No. 1 weather-related cause of death worldwide and in the United States. Miller is one of the many researchers globally who are expanding our understanding of what heat does to the body and how to counteract its effects. Recently, his Texas State University lab has had success cooling participants using a body bag full of ice—a tactic that is affordable and transportable for emergency responders. Rapid cooling is life-saving medicine.

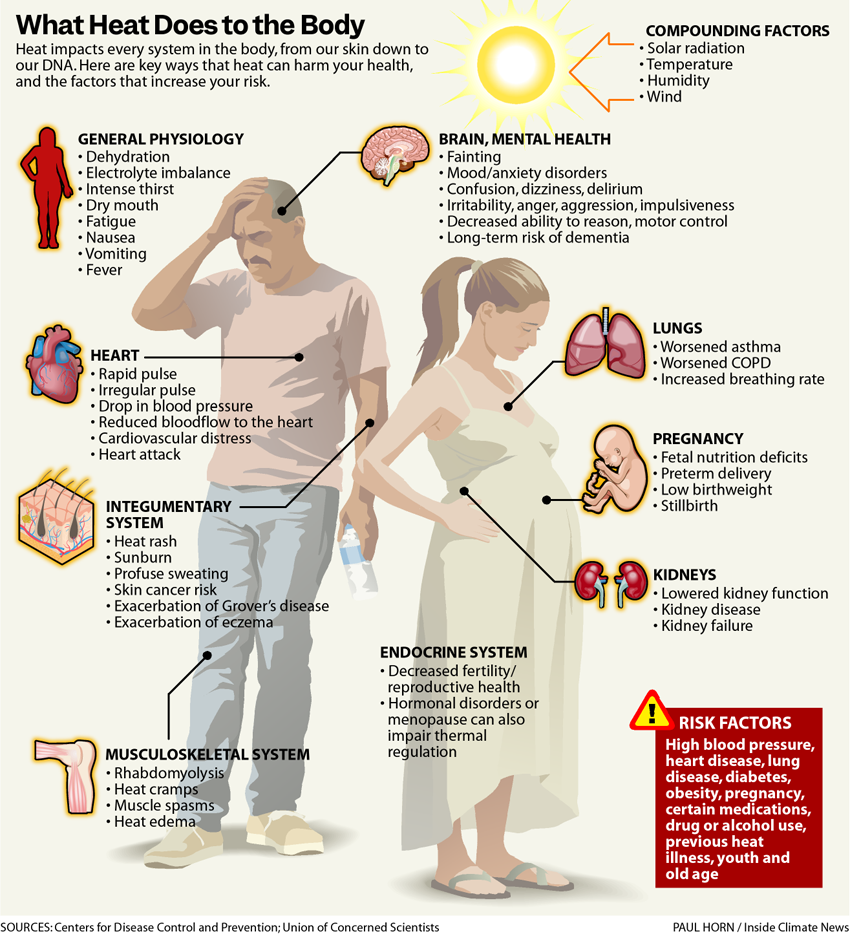

But heat’s impacts aren’t limited to these obvious moments of emergency. It has a bearing on nearly every aspect of human health, from our skin down to our DNA.

That means long-term exposure to high temperatures—increasingly common as the Earth warms—is causing cumulative harm to our bodies and minds.

About This Story

This is the second in an occasional series of stories exploring the effects of rising temperatures across Texas. The project is a collaboration between Inside Climate News, the San Antonio Express-News and Public Health Watch.

How Heat Impacts the Body

At the start of this summer, more than 255 million Americans—or two-thirds of the country’s population—lived in areas experiencing life-threatening levels of extreme heat.

But far too few people know the signs indicating exposure has gone from uncomfortable to dangerous.

Heat illness is a collection of medical conditions like heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heat rash and heat stroke—the last of which can be deadly.

After about 30 minutes at a 105-degree core body temperature, cells begin to break down and rupture, unleashing their contents into the bloodstream. As the kidneys and liver kick into overdrive to try to filter out those infiltrators, the organs can fail, leading to cardiac arrest and death.

“The body essentially treats that like a systemic infection,” Miller said.

As heat stress worsens and a person gets dehydrated, their mental function suffers, said Lisa Patel, a pediatrician and executive director of the Medical Society Consortium on Climate & Health.

“It’s almost like you’re drunk,” she said. “You’re going to make poorer and poorer decisions that place you at higher and higher risk for a really bad outcome.”

Symptoms of heat stroke include headaches, dizziness, loss of consciousness, seizures or even a change in personality as the central nervous system goes haywire. The key difference between heat exhaustion, a milder form of heat illness, and the more serious heat stroke is brain dysfunction: a person experiencing heat stroke no longer has their full mental faculties.

“If [someone] is confused in the presence of heat, that is heat stroke until proven otherwise,” said Rosemary Sokas, a professor of human science at Georgetown University.

Heat deaths are undercounted globally, partly because they’re often attributed to the literal physical process that led to a death—like cardiac arrest or kidney or liver failure—rather than the underlying trigger.

“It’s almost like you’re drunk. You’re going to make poorer and poorer decisions that place you at higher and higher risk for a really bad outcome.”

— Lisa Patel, Medical Society Consortium on Climate & Health

Heat stroke is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate attention, and Miller emphasized that a delay in treatment could be a matter of life or death.

“If I call the hospital and I send you on an ambulance without treating you first, you are cooking internally the entire time you’re on the ambulance ride, the entire time you’re in the hospital waiting room,” Miller said.

“The No. 1 predictor of whether or not you’re going to live or die if you have heat stroke is how long your body temperature stays above that 105 Fahrenheit threshold,” he said.

Beyond Heat Stroke: Heat and the Mind

In addition to the immediate dangers of heat illness, heat can have less obvious health impacts in both the short and long term. Mood disorders, confusion, irritability, trouble focusing—heat can trigger them all, and researchers are continuing to uncover its impacts on the brain.

Researchers found last year that heat-related illness— hyperthermia—can harm problem solving, reasoning, planning, working memory and inhibition control. High temperatures also hinder motor cortical control, which coordinates movements like walking or reaching.

Researchers have found that emergency department visits for mental health crises spike during heat waves. Increases in drug overdoses have also been linked to the weather phenomenon; Yale University researchers found last year that heat exposure could be contributing to 150 excess overdose deaths nationally every year.

New research finds that experiencing heat-related illness can lead to elevated risk of dementia later in life, and that air pollution can also exacerbate dementia, adding to a long list of ways in which the two climate risks amplify one another’s dangers.

Heat also presents risks for children. Rising temperatures worldwide are making it harder for students to learn, impacting focus, memory, cognitive skills and more, and even short-term exposure to heat has been linked to lower student test scores and grades.

Heat Risks Compound for the Old and Young

Between July 2023 and June 2024, the humanitarian group Save the Children found that one third of the world’s children faced extreme heat waves—twice as many as the previous year. They are especially vulnerable, overheating more quickly because their bodies are less efficient at regulating temperature.

Heat combined with air pollution intensifies health risks for people of all ages, but Patel noted that children—with their smaller airways—can be affected more acutely by air pollution.

Climate change makes it all worse. In recent years, Patel has seen young patients come in with extreme symptoms related to heat and air pollution that she wouldn’t have expected.

In 2020, during California’s severe wildfire season, she treated a 16-year-old who had immigrated unaccompanied from Mexico and was working for a construction company hauling brick in 108-degree weather. He had been hospitalized for rhabdomyolysis, a life-threatening condition in which the body’s muscles begin to break down and release their contents—like proteins used to transport oxygen—into the bloodstream.

Patel’s patient—severely dehydrated and overworked—was hospitalized for kidney damage.

At the same time, she’s seen little recognition from patients and families—and even other physicians—about the rising dangers of heat.

“The heat is getting worse and worse and worse, and we are not building people’s awareness capacity or the infrastructure for people to be able to stay safe,” Patel said.

These dangers are highest for people who are un- or underinsured, have no air conditioning or face other financial hardships.

Surviving a brush with extreme heat isn’t the end of the ordeal. Dehydration, a common side effect of continued heat exposure, can also cause permanent kidney damage. Having a heat stroke can increase the risk of another one within the next two years, research shows.

Heat is also more dangerous for the elderly, pregnant people and individuals with chronic conditions, like diabetes or heart disease, which make it harder for the body to deal with heat stress. Older adults can end up with a triple whammy: Changes in sweat production as their bodies age make it harder to cool down, and they’re more likely to have chronic conditions or take prescription medications that impact their ability to thermoregulate.

Earlier this year, a study found that cumulative exposure to extreme heat can speed up the process of aging at the DNA level. The study looked at epigenetic age, a measurement of how well the body is functioning that looks at DNA methylation—a process of chemical modification that changes how genes are expressed as a person ages.

Eun Young Choi, the lead author on the study, equates methylation to turning a light switch on or off: while DNA is a blueprint fixed at birth, methylation determines which parts of that blueprint get activated or deactivated as we age. That process is highly impacted by environmental exposures like stress, pollution or temperature.

“The physical toll of heat might not show up right away as a diagnosable health condition, but could be taking a silent toll at the cellular or molecular level of our body,” said Choi, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Southern California.

That’s what the team’s research found. Residents of neighborhoods with more days of extreme heat—as in Phoenix—experienced up to 14 months of additional biological aging compared to counterparts in cooler areas like Seattle, about the same difference caused by smoking or heavy drinking.

In other words, living in a hot environment could tack on an extra year to your biological age, even controlling for factors like income, race, education and whether you smoke, drink or exercise.

How to Protect Yourself from the Heat

As heat waves intensify everywhere, it’s crucial to adopt habits that protect yourself and your family from high temperatures.

Rose Jones, a medical anthropologist and educator who has warned of heat’s harms for several years, said that many public safety materials about heat are misleading or unclear. For example, directives to stay hydrated can be confusing for people who think any liquid will help and rely on sodas or alcohol. Alcohol and sugary drinks can dehydrate. Water, green tea or other clear liquids are the way to go.

Adelita Cantu, a registered nurse and associate professor at the University of Texas Health San Antonio School of Nursing, suggested wearing broad-brimmed hats; placing cool, damp towels in areas that can quickly access a large blood supply, like the back of the neck or the groin; and eating protein to mitigate the symptoms of dehydration.

Wearing loose-fitting clothing with light, long sleeves can also be helpful, she said, both for protecting the skin from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays and for bringing the cooling effects of evaporating sweat back into the body.

If someone faints or shows symptoms of heat stroke, call 911 immediately.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowOutdoor workers are at elevated risk of heat illness, especially when they’re new to the job, have underlying medical conditions, are older or are performing taxing physical work that produces more body heat, such as lifting heavy items or climbing ladders.

Heat stroke risk is highest at the beginning of the summer, when people’s bodies are least prepared to handle the heat. That’s true for everyone but, in particular, has implications for outdoor workplaces. Experts emphasize the importance of acclimatization—easing a person into conditions that invite heat stress. Starting off with a few hours of heat exposure per day can help build up the body’s tolerance.

But acclimatization’s benefits are lost quickly. Two weeks without heat-stress conditions, and a worker will need to be re-acclimatized.

Clinics Are Trying to Help, But Politics Gets in the Way

Heidi Burford-Bell is the executive director of Snake River Community Clinic. It’s the only free clinic in a rural part of Idaho she described as a “medical desert,” 100 miles from the nearest metropolis. It relies on part-time workers and volunteers to serve thousands of patients a year.

Burford-Bell is seeing more patients with severe dehydration who don’t know why they’re so tired, particularly unhoused people or outdoor workers. Stocking water and hydration packs in the clinic has been a crucial intervention, she said.

Burford-Bell has also noticed dehydration-related kidney problems and skyrocketing blood sugar in unhoused patients whose insulin medication sits out in the heat, losing its effectiveness. This summer, the clinic had one case of rhabdomyolysis.

Unhoused and uninsured patients are at heightened risk of illness and death from extreme heat, making free clinics a crucial part of lifesaving frontline interventions.

Youssef Motii, executive director of Oceana Community Health, a clinic in Southeast Florida, has seen patients with insufficient or no housing suffering from both acute and long-term heat health impacts. Dehydration. Heat stroke. Skin cancer from continued, unmitigated exposure to ultraviolet rays.

“We talk about dehydration and heat strokes all the time, because those are the big buzz words, but we often overlook the chronic UVB exposure these patients have,” Motii said.

Burford-Bell and Motii’s clinics are two of more than 140 participating in an initiative led by the disaster relief and health organization Americares, which aims to equip health clinics with low-cost heat action plans as extreme heat becomes a chronic threat. So far, the effort has reached clinics in 30 states, including Texas.

The project, developed with researchers from Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, includes an online portal for clinics to access a heat-health action plan tailored to their patient population and organizational constraints.

Using this plan, Motii’s clinic in Florida started outreach on heat health impacts in January, three months earlier than in the past. This summer, despite serving more patients overall, the clinic saw a 31 percent decrease in patients with heat-related illness as their chief complaint compared with the previous year.

“Truly, this is a testament to how important it is to educate your patients and keep them informed so they themselves can feel empowered to make informed decisions about their health,” Motii said.

But in many parts of the country, innovative approaches to treating heat and raising public awareness are still rare.

“I look at the public health messaging for heat and it’s abysmal,” said Jones, the medical anthropologist. “It’s generic, it’s stereotypical, it’s a one-size-fits-all scenario that we know in public health never works.”

As heat risks rise, the federal government is eliminating climate and health research, yanking funding for programs aimed at low-income communities and people of color hit harder by climate impacts and pushing fossil-fuel expansion that will warm the planet further.

In Texas—where Jones lives and works—legislators have banned cities from requiring heat protections for workers and have limited how educators can explain critical climate information. Jones said these changes have created a culture of fear among health professionals, quelling discussion of the established health dimensions of climate change.

As floods, hurricanes, droughts and wildfires worsen alongside heat, it’s more important than ever to deliver clear and useful public health information that people can use, Jones said, and that explains how these crises are connected.

“We are now at a point where it’s extreme events and it’s all of them, because they’re filtering into each other,” she said. “From a public-health perspective, we’ve got to do better with that messaging.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,