Western States Brace for a Uranium Boom as the Nation Looks to Recharge its Nuclear Power Industry

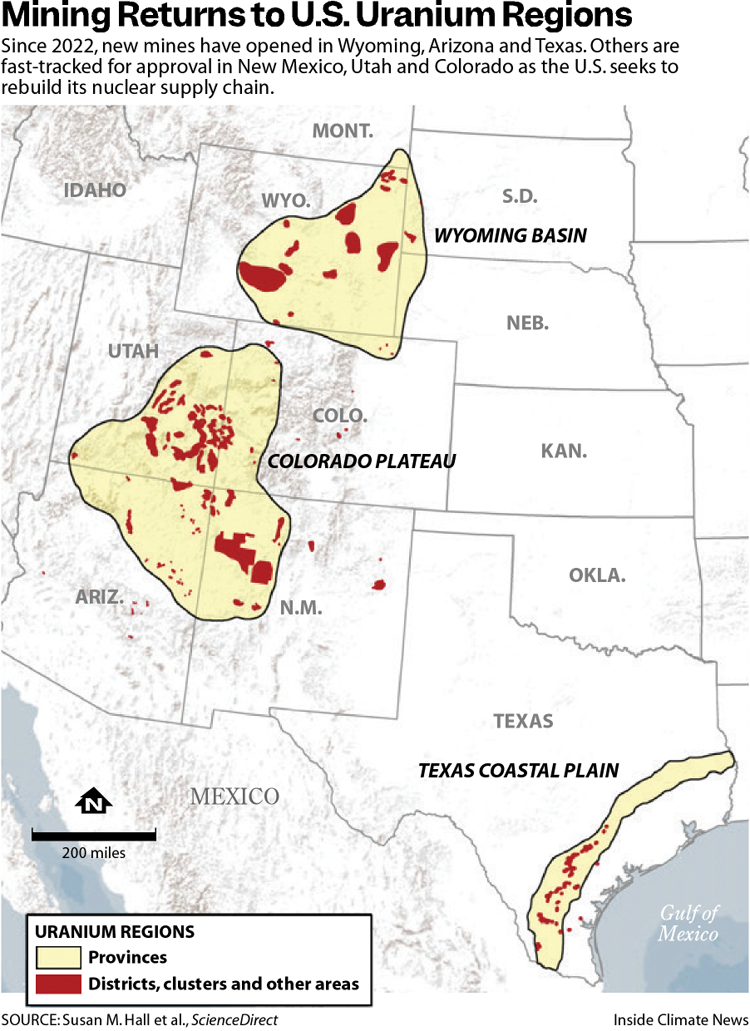

After years of federal efforts to revive nuclear power, old mines are stirring again in Wyoming, Texas and Arizona, while new ones line up for permitting expedited by a Trump executive order.

BAIROIL, Wyo.—The remote dirt road through dusty fields of sagebrush that John Cash drove along in June seemed to pass little of economic value. But his car was, in fact, rattling towards the top-producing uranium mine in Wyoming.

In 2022, the Lost Creek Mine became the first of several such sites across the West to restart operations as the U.S. scrambles to reestablish a domestic supply chain for nuclear fuel.

Cash, the CEO of UR Energy, which operates the Lost Creek Mine, believes more mines will come online in the years ahead.

“This [area] is loaded with uranium,” he said amid the vast, arid expanse of Wyoming’s Great Divide Basin. “I promise you right now, if I drilled a hole right here, we would hit uranium.”

Newly revived mines are also humming in Texas and Arizona, their owners hopeful that a boom in demand lies ahead. Ten uranium mines operate in the country today, up from three in 2021, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Agency. Company announcements and public records show dozens of others on standby for reopening or queued up for permitting in Colorado, Utah and New Mexico, with at least four currently fast-tracked for approval under recent executive orders.

“We’re right at the edge of a good little uranium mining boom,” said Travis Deti, executive director of the Wyoming Mining Association. “We’ve been off the playing field for decades on some of this stuff.”

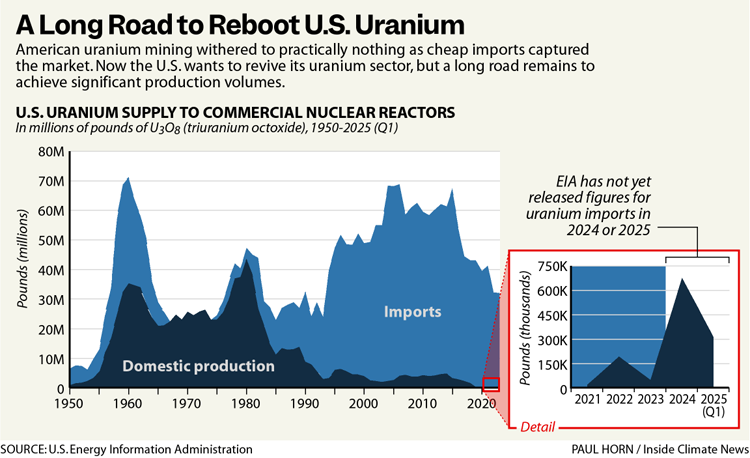

For more than a generation, many of these sites sat dormant, stifled by a cheaper imported supply and modest demand from a stagnant nuclear power sector. However, uranium markets have recently re-awakened: Spot prices doubled between 2022 and 2024, driven by global supply chain disruptions, geopolitical tension and lofty expectations for a renaissance of American atomic power.

Lately, a buzzing landscape of nuclear startups has stirred excitement with announcements of ambitious plans for advanced reactors to power artificial intelligence and other heavy industries across the country. But almost all of these companies are waiting for the U.S. to rebuild a nuclear fuel supply chain before they can even power up their prototype units.

“Expectations for uranium demand have been growing,” said William Freebairn, an associate editorial director at S&P Global Commodity Insights. “But this kind of demand is slow to show up.”

Investor appetite for uranium started to increase around 2022, he said, “as climate concerns became more prominent.” Uranium is processed and enriched into nuclear fuel that provides abundant energy without carbon emissions, although it poses other significant health and safety risks.

Presidential administrations since Barack Obama’s have pushed to increase domestic production of uranium fuel to supply the national nuclear sector, but that goal remains years away. President Donald Trump issued a flurry of executive orders this year to streamline permitting, expedite environmental reviews and impose tariffs on imports that compete with American products.

Despite the recent activity, the U.S. still has a long way to go before it could even come close to meeting its nuclear needs with uranium from domestic mines, Freebairn said.

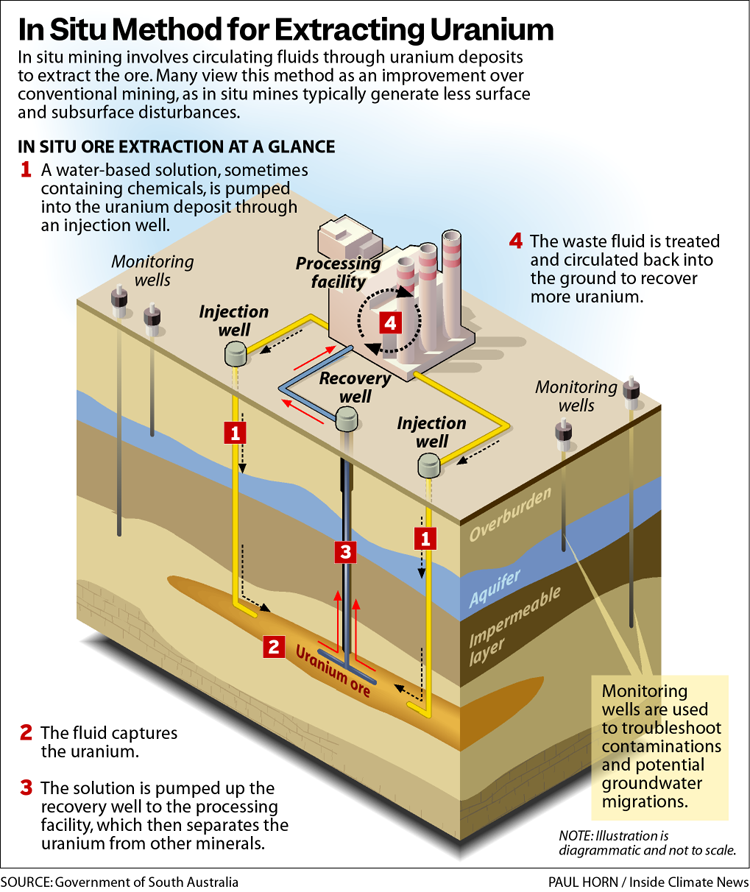

Unlike pit mines, which scrape away acres of earth, most modern uranium extraction projects drill hundreds of wells, inject them with solvents and suck up the mineral slurry they create. This method has a much lighter impact on the surface but can contaminate or deplete freshwater aquifers if improperly managed.

In Wyoming, several hundred wells churn out a modest 28,000 pounds of uranium oxide per month at the Lost Creek mine. The mine is licensed to produce more than 1.2 million pounds of uranium oxide concentrate annually, according to UR Energy, but uranium miners are still waiting for the development of a domestic nuclear supply chain before ramping up production.

Supply Chain Bottleneck

For now, American uranium production remains a dribble. Despite recent steep increases, total output in 2024 was less than 2 percent of the country’s peak production in 1981. The U.S. lacks the infrastructure to transform uranium oxide concentrate, known in the industry as “yellowcake,” into the uranium hexafluoride gas used for enrichment. About 99 percent of the feedstock consumed by U.S. power plants is imported, and much of that uranium is enriched in Russia, despite the prohibition on importing Russian uranium then President Joe Biden signed in May 2024. The ban doesn’t fully go into effect until 2028.

“Uranium mining, uranium processing and uranium enrichment have all largely been offshored because they could do it cheaper,” said Rusty Towell, director of the Nuclear Energy Experimental Testing Laboratory at Abilene Christian University. “That whole supply chain was weakened.”

In the U.S., just one commercial plant converts uranium into the gaseous form required for enrichment and only one commercial plant enriches that gas into nuclear fuel at the scale required to fuel power plants. No facility can produce significant volumes of the higher-grade fuel used by new reactor designs—High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium, or HALEU. That also comes primarily from Russia, though the Department of Energy has posted billions in grant funding for private-sector enrichment projects in the U.S.

“The U.S. [government] is moving very fast on this,” said James Walker, CEO of a startup called Nano Nuclear Energy and a former nuclear engineer at the U.K. Ministry of Defense. “Now the pressure is on everybody to ramp up as fast as they can.”

A whole cluster of advanced nuclear startups like Nano eagerly awaits the availability of American HALEU to begin testing their reactors, and they’ll purchase the new enrichment facilities’ product as soon as it becomes available, Walker said.

However, even a booming domestic market for nuclear fuel doesn’t guarantee that American uranium miners will supply the needed raw material. New enrichment projects could continue to import uranium mined overseas—but government policies are making that harder, including with the Biden administration’s ban on imports of Russian uranium.

“We are making investments to build out a secure nuclear fuel supply chain here in the United States,” the announcement of that ban stated.

This year, Trump imposed tariffs on imports from 70 countries, including the top uranium producers: Kazakhstan, Canada and Namibia.

“As long as we’re keeping that foreign uranium from coming in, then I think there is hope for domestic production,” said Brent Elliott, a geologist with the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas. But if “we can get it cheaper somewhere else, then that will more likely be the case.”

A Flurry of New Mines

In Wyoming, home to the nation’s richest known uranium deposits, three other companies have recently joined UR Energy in ramping up operations. To the south, in far western Colorado, Canadian firm Anfield Energy announced plans in August to begin exploratory drilling at an abandoned, 2000-acre pit uranium mine.

In Utah, Anfield’s Velvet-Wood project received an expedited environmental review that lasted just two weeks due to a March executive order from the White House.

“This approval marks a turning point,” said Interior Secretary Doug Burgum in a press release at the time. “By streamlining the review process for critical mineral projects like Velvet-Wood, we’re reducing dependence on foreign adversaries.”

The reviews of several mines in western New Mexico were also fast-tracked and are expected to conclude in late 2027. They include the Crownpoint-Church Rock and La Jara Mesa projects by Australian miner Laramide Resources, as well as Energy Fuels’ Roca Honda project in the Cibola National Forest.

On federal lands, where many of the reopened mines are located, digs for minerals are still governed by the Mining Act of 1872. Originally passed to draw settlers to the West, it declares all mineral deposits “free and open to exploration and purchase.” The law has enabled some mines to open in areas that are culturally important to tribes, critical habitat for vulnerable species or revered for recreational and scenic values, often over local opposition.

Some of the fast-tracked New Mexico mines border the lands of the Acoma and Laguna pueblos. In the nearby Navajo Nation, the new activity has sparked concern.

The Navajo Nation “continues to be affected—not only from abandoned uranium mines and mill sites—but also from other contaminants,” said Perry Charley, chair of the Diné Uranium Remediation Advisory Commission, at a public meeting in August in Shiprock, New Mexico.

From 1944 to 1986, mining activities left more than 500 abandoned mines and an enormous amount of uranium waste in various regions of Navajo land.

Numerous peer-reviewed studies of the Navajo Nation have shown widespread groundwater contamination by uranium, as well as other elements released by the mining process, including arsenic, vanadium, manganese and lithium.

“Though uranium mining ceased on the Navajo Nation in 1986, the contamination left from these operations still represents a significant danger,” said a study from 2019.

Recent studies have linked proximity to abandoned uranium mines with increased risks of autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases on the Navajo Nation. Uranium concentrations in urine samples of Navajo women are almost three times higher than the national median and are associated with significantly increased risks of preterm births, according to studies in 2020 and 2023.

Navajo people’s cancer diagnosis rate is 6.3 times higher for gallbladder cancer, 3.2 times higher for stomach cancer, 1.9 times higher for kidney cancer and 1.8 times higher for liver cancer than white populations in New Mexico and Arizona, according to a 2023 report from the Navajo Epidemiology Center.

On the eastern edge of Navajo land, at the Church Rock site, a dam failure in 1979 released 94 million gallons of waste fluids into the Rio Puerco, the largest radioactive material spill in U.S. history. Church Rock is among the sites currently undergoing expedited environmental review to resume production.

“These communities are still trying to clean up from the last time this happened,” said Amber Reimondo, the energy director at the Grand Canyon Trust, a nonprofit advocating for protection of the Grand Canyon and Colorado Plateau. “For years, tribes have been reassured that the problems of the past are just that—problems of the past—and that now we have environmental laws that are supposedly protecting them.”

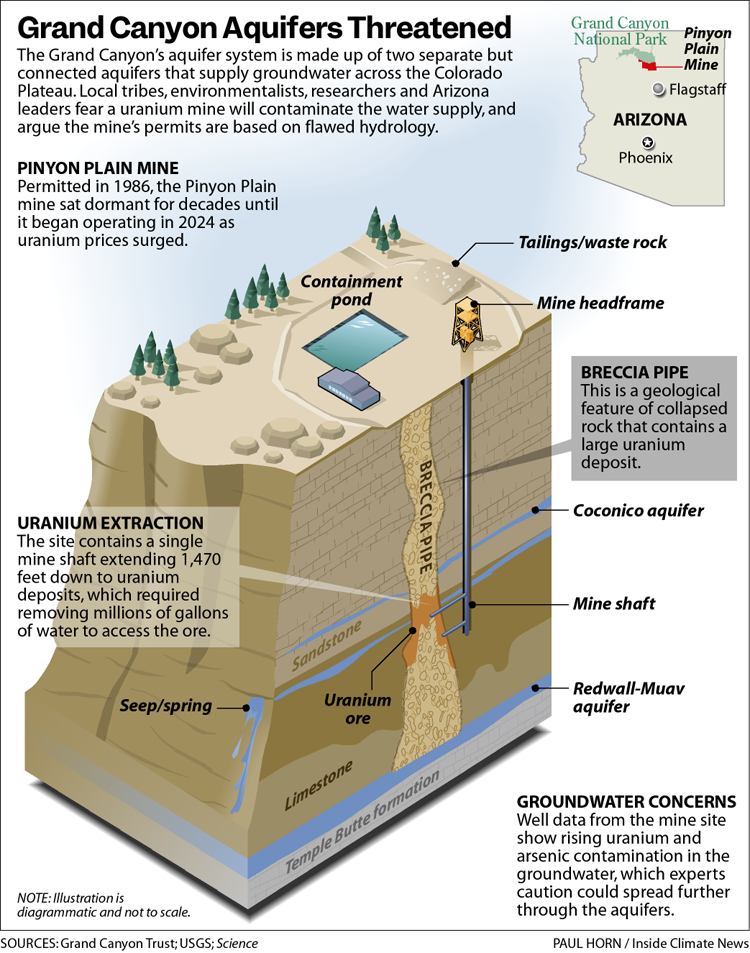

At the Navajo reservation’s western edge, uranium production began last year at the Pinyon Plain Mine, nestled among pinyon pine trees in the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni National Monument, less than 20 miles from the Grand Canyon’s south rim in Arizona.

The mine operator, Energy Fuels, began trucking its uranium product through Navajo territory in July 2024, but was forced to stop after the tribal government issued an order banning unauthorized transport of radioactive material.

“Anyone bringing those substances onto the Nation should undertake that activity with respect and sensitivity to the psychological impact to our people, as well as the trauma of uranium development that our community continues to live with every day,” former Navajo Nation Attorney General Ethel Branch said in a statement at the time.

Later, the tribal government and Energy Fuels negotiated an agreement to resume transport of uranium from the Pinyon Plain Mine across the Navajo lands.

“Energy Fuels is pursuing an aggressive plan to quickly increase short-term U.S. uranium supply,” company CEO Mark Chalmers said in a press release this year announcing record production at Pinyon Plain.

Energy Fuels did not respond to requests for comment. The company has a long list of mines it’s working to bring back online across Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, according to public announcements.

Groundwater Concerns

Permitted in 1986, the 14-acre Pinyon Plain Mine sat dormant for decades, like hundreds of other sites in the country, waiting for uranium prices to rebound. When they did, the U.S. Forest Service cleared it to begin operations for the first time last year although it last cleared federal environmental review almost 40 years ago. The decision prompted protests from local tribes, Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs and Attorney General Kris Mayes.

“We must protect the water supplies,” Mayes said in an August 2024 statement calling for reevaluation of the mine. “The risks are too great to ignore.”

The site contains a single mine shaft extending 1,470 feet down to the uranium deposits, and the company removed millions of gallons of groundwater to access the ore. The mine and others like it pose threats to the region’s network of interconnected aquifers that stretches across the Grand Canyon region, according to research published last year by Karl Karlstrom and Laura Crossey, Emeritus professors of earth science at the University of New Mexico.

“Energy Fuels doesn’t know how much their mining is contaminating the deep aquifer, and USGS doesn’t know, and we don’t know,” Karlstrom said. “Caution is needed.”

In an interview, both researchers said the Pinyon Plain mining plan assumes that two underlying formations holding water, the upper Coconino aquifer and the lower Redwall-Mauv aquifer, aren’t connected. But ample regional science shows that’s not true, they said; water moves between them.

The Redwall-Mauv aquifer feeds springs across the region, some of which provide drinking water for the Havasupai Tribe.

“Current well data are insufficient to rule out a connection between the two aquifers,” wrote the Environmental Protection Agency in a review of the mine following Karlstrom and Crossey’s study. But the agency noted that USGS data from the mine’s well sites show elevated levels of uranium and arsenic contamination, and that it is unclear how or if it will spread.

“The potential for groundwater contamination resulting from operations at the Pinyon Plain Mine site cannot be assessed fully without additional investigations,” the EPA review concluded.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe uranium mining revival has churned up similar concerns in the savannah of South Texas. Encore Energy, based in the Gulf Coast city of Corpus Christi, started production at its Rosita site in November 2023 and its Alta Mesa site in June 2024. In August, it acquired 5,900 more acres adjacent to Alta Mesa, where it plans to begin drilling in October. Another Corpus Christi-based company, Uranium Energy Corp., expects to start mining at its South Texas sites in early 2026.

One rural groundwater conservation district is fighting the renewal of an old, unused mining permit UEC holds for a site in Goliad County.

“We are extremely concerned that UEC’s uranium mining activities will lead to groundwater contamination,” said a request for a hearing on the mine permits filed by the district with Texas’ environmental regulator late last year.

The site of Uranium Energy Corporation’s inactive mine in Goliad County. Credit: Dylan Baddour/Inside Climate News

Faultlines and abandoned oil wells connect the mining area to freshwater aquifers, the district claims. Some 30 households, a church and about 400 cattle drink from wells in the area surrounding the mine. Groundwater levels there dropped 15 feet between 2000 and 2022, the district said.

The Goliad site will use about 130 million gallons per year, according to Art Dohmann, vice president of the Goliad County Groundwater Conservation District. But mining is exempt from groundwater permitting requirements under Texas law, he said.

“This may cause more wells in the area to go dry,” the district wrote in comments to the state.

In August, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality voted unanimously to grant the district’s request for a hearing on the permit. UEC did not respond to requests for comment.

Separate state permits authorize UEC to inject up to 105 million gallons of mining wastewater underground for disposal every year at its Goliad site. UEC has four other projects under development in South Texas.

The company, which calls itself “America’s largest and fastest growing supplier of uranium,” also owns sites in New Mexico and Wyoming, where its Christensen Ranch mine began production last summer and its Sweetwater Uranium Complex was selected in August for the fast-tracked approval authorized by President Trump’s executive order.

UEC calls Sweetwater “the largest uranium complex in the U.S.” It encompasses 20,000 acres of exploration and mining rights in Wyoming’s Great Divide Basin, and sits only a few miles from UR Energy’s Lost Creek Mine, where Cash, UR Energy’s CEO, was surveying his company’s project.

Before UEC can even develop the site, the expedited review is expected to take 18 months, according to a federal permitting tracker.

Drilling Uranium

On a hot morning in June, three men and a 25-foot-tall winch pulled piping from the ground at the Lost Creek mine in Wyoming. They had just completed a new uranium well.

Cash, a trim man with brown hair lightly graying on the sides, inspected a slab of wood containing samples of wet earth taken every five feet down the well. A chunk he scooped up was a deep green, indicating it probably contained uranium.

“For a geologist, it’s like reading a book,” said Cash, who has a master’s degree in geology and geophysics from Missouri University of Science and Technology.

Lost Creek extracts uranium using in-situ recovery—ISR mining—a process pioneered in Wyoming in the 1960s. Over the eons, water carried uranium off the granite mountains surrounding the Great Divide Basin, burying it in the sandstone. Water is now used to draw it back out. The company drills wells patterned like the five-side of dice and then injects a leachate—water, oxygen, CO2 and occasionally soda ash at UR-Energy’s project, according to Cash—into the exterior four shafts. When that stew is pumped back to the surface through the center pipe, it’s full of uranium.

Wells’ surface impacts bother Cash, he said, looking out over the site. “I wish we could do this with less disturbance.”

But if this was an open pit mine, a crater would displace the vegetation on the surface and “this would all be gone in perpetuity,” he added. Instead, the company will replant native sagebrush and grasses, Cash said.

Hundreds of wells surrounded the site’s processing facility—a concrete and steel warehouse where employees wearing radiation-monitoring badges oversee chemical processes that turn uranium-filled slurry into yellowcake, the base ingredient of nuclear fuel.

Water that isn’t reused, about 21,600 gallons a day, according to Cash, is treated and disposed of underground.

Lost Creek has detected groundwater contaminated by what the company injects—moving “where it shouldn’t move”—four or five times since 2013, Cash said. If left alone, it could spread to freshwater sources. This is “exceedingly rare,” and each time it has happened, UR Energy has successfully prevented an escape, he said.

Employee and environmental safety are among Cash’s top concerns, but he feels U.S. nuclear regulations often hamper innovation and curb profit margins. He chaffed at the fact that UR Energy was required to install and maintain a full-blown weather station at Lost Creek, and wondered why his company had to take groundwater that was already undrinkable and make it slightly cleaner, but still unpotable, before disposal.

“We need to be protective,” he said. “But we don’t need to be hyper-protective.”

Cash left Lost Creek for another UR Energy project, which would revive the Shirley Basin mine some 80 miles east at the foot of the Laramie Range. On his way that June day, he passed another potential mine, the Lost Soldier project, a claim he isn’t sure the company will ever develop.

“There’s a lot more work we need to do,” Cash said.

Noel Lyn Smith contributed to this story.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the amount of uranium the Lost Creek Mine can produce. The mine is licensed to produce 1.2 million pounds of uranium oxide concentrate a year, rather than having a capacity to produce 2 million pounds per day.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,