Last summer, Brice Acton watched drought devour the fields of his small family farm in southern Ohio. It took just a matter of days. First, the corn stalks in sandy soils dried out. Within two weeks, plants in the clay soil at the upper end of his property were parched.

“When they burn up, they go from green to brown,” said Acton, who grows grain corn, soy, wheat and flowers in Ross County. “And you just slowly watch a whole field die.”

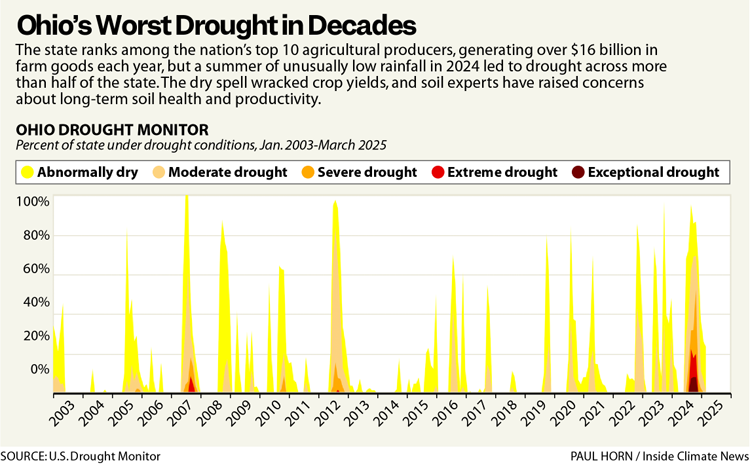

In 2024, Ohio faced its most severe drought in a century as central and southeastern regions went weeks on end without rain. At the end of September, the U.S. Drought Monitor, a decades-old partnership of meteorologists and climatologists who monitor rainfall across the country, reported that 98 percent of the state was “abnormally dry or worse.” In its weekly Crop Progress & Condition Report, the U.S. Department of Agriculture warned on Sept. 22 that a third of the state’s corn and soy were in “poor or very poor crop condition.”

The dry spell in Ohio came at a devastating time. Less than a quarter of soy and corn crops were ready for harvest. Growers like Acton, a fifth-generation farmer who also raises sheep, hogs and chickens, were trying to decide whether to reap immature crops or risk them drying and dying when the unimaginable happened.

Rain fell with a fury. Hurricane Helene spun north in late September and doused the region for two days straight. For the parched crops, it was too much, too fast.

Acton’s soybeans proved particularly vulnerable. “When [Helene] came through, the beans were mature and ripe. The minute they got wet and it was warm, they did exactly what Mother Nature intended. They began to grow, still attached to the plant.”Acton said he lost about a third of his expected profit, as acres of crops were unfit for harvest. Lower yields also meant less feed for livestock, forcing Acton to use oats instead of the grains that he typically grows.

Ohio offers some cautionary tales about possible long-term shifts in the weather, said Dianna Bagnall, a soil physicist and program director for the Soil Health Institute, a decade-old nonprofit in North Carolina.

The combination of drought and heavy rainfall in that state last year could lead to poor soil health for farms, she said, and may be part of a developing pattern that could vex traditional planting seasons.

Ohio’s agricultural sector production was valued at more than $16 billion in 2023, according to USDA economic research records. The state ranks among the top 10 in the country for production of grains, greenhouse crops, and hogs, but its 74,000 farms, about 65 percent which are less than 100 acres, face increasingly challenging climate conditions.

Bagnall, whose group advises farmers, studies the rate at which soil can absorb and retain water. When poor infiltration develops, “there’s this kind of feedback loop,” she said, and crops can’t cope. “If we don’t have the infiltration to capture the water that we want, now we’re losing our nutrients and our topsoil because the water’s running off. Then the next time that it rains, it’s going to be even harder to capture that water,” she said.

Water retention depends on soil’s ability to form “aggregates,” crumbs of organic matter and minerals that act like sponges. In healthy soil, these aggregates are formed by insects, fungi, bacteria and decaying plant matter. All sorts of life help to stabilize the structure of the topsoil, but these life forms are directly impacted by soil temperature and moisture.

Elizabeth Rieke, a microbiologist at the Soil Health Institute who oversees programs that measure soil health, said that prolonged drought—a rain deficit lasting multiple months—can damage the microbial communities in the soil that are critical for water retention and crop nutrient uptake.

During drought, microbes may go dormant and pause water uptake and nutrient cycling or, as Rieke puts it, “all the different beneficial things that they do for us and plants.” “Microbes are resilient,” she said, “but if we see these longer-term shifts, it can be detrimental to systems over time.”

Like many farms in Ohio, Acton Family Farms depends on rainfall as its primary water source. The farm isn’t located near a body of water for irrigation. And even with an on-site 800-gallon water trailer, manual watering is exhausting. “I can average four trips per day,” from trailer to crops, “five per day if I’m doing good,” Acton said. He estimates it takes 35 trips to quench a single acre.

After last summer, Acton worries about the microbial communities in his fields. “I know that some of those soil bacteria and things can go dormant. But can they go dormant for a prolonged period?” he said. In 2024, Acton measured carbon dioxide production—a commonly used proxy for microbial activity—in several of his fields. He plans to sample the same places this spring, to see how it has changed.

Farmers who plant cover crops and avoid tilling or disturbances to soil structure will have hardier land when extreme drought comes, Bagnall and Rieke said in separate interviews. But that requires time, money and planning. “It can take years to get our soil to the point where our program is really working and we have resilient soil in place,” Bagnall said. “We can’t always wait until drought happens and then change something.”

Acton has tried regenerative practices on his farm. He holds a bachelor’s degree in agronomy and crop science from Ohio State University and is chairman of the Ross County Soil and Water Conservation District Board of Supervisors, where he works with local landowners to protect and manage natural resources.

Acton hasn’t tilled his fields in decades, he said. But many of his neighbors continue to do so—even after he has tried to convince them to move toward some proven conservation methods. “The most expensive phrase on the farm is, ‘that’s how we’ve always done it,’” Acton said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowAll told, it was a rough year in Ohio for crops. The average corn yield in the United States reached a record high in 2024, but Ohio’s corn production fell 16 percent from 2023. Soybean production was down 8 percent. Acton said he and farmers across Ohio are still coping with fears from the last unpredictable growing season.

“Every year is a new year,” Acton said recently. But the economic toll of climate disasters has taken a mental toll. “I’m worried if things like this keep happening, how it will play out with my friends and fellow farmers.” His memory of last summer is still painful. “We would see the rains building, and then they would disappear,” Acton said. “Then, all of a sudden, they quit even building.”

There are several federal and state initiatives that have encouraged farmers to adopt healthier soil management practices, such as the USDA’s Conservation Stewardship Program, which finances new and continued conservation practices on working lands.

But President Donald Trump’s executive order, “Unleashing American Energy,” ordered federal agencies to immediately pause the disbursement of funds appropriated by the Inflation Reduction Act, the flagship climate law of the Biden administration.

The freeze impacts many federal funds for farmers across the country, including the Conservation Stewardship Program, the Regional Conservation Partnerships Program, and the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, all managed by the USDA.

As a result, farmers who had signed federal contracts to help implement climate-resilient adaptations are in limbo. They’re not sure when, if ever, they’ll see the dollars they were promised.

“Nobody saw any of this coming,” Acton said about the federal freeze. “There’s no new funding.” He’s worried, with the rapid pace of budget cuts in Washington under the new Trump administration, that the cuts will extend beyond conservation programs and impact the Farm Bill passed in 2018 during Trump’s first years in office

“We’re kind of being told now that the Farm Act is going to get frozen. There’s no proof of it now, but it would make sense,” Acton said. “And if that gets frozen, it’ll be a nightmare situation.”

For now, Ohio farmers can qualify for relief through the state. In February, the Ohio Department of Agriculture announced it would distribute $10 million in drought funds to farmers in 28 counties designated as “primary natural disaster areas” in 2024.

Soil and water conservation districts administer the funds, and in Ross County, that responsibility falls to Acton. He and his board have begun approving payments to over 150 producers.

Will the relief funds be enough for farmers to recover from a dry year, or will they continue to feel the aftershocks of the drought?

“It’s still too early to tell,” says Acton. “The weather is always a fear, you know? We can change a lot of things with our crops. But we cannot affect the weather.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,