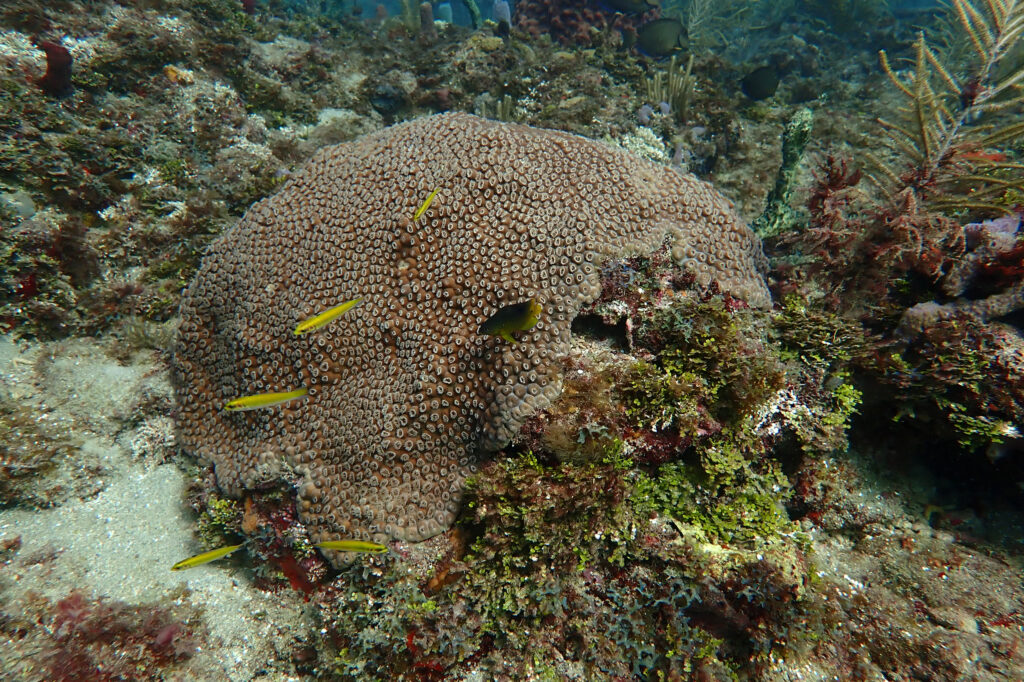

Beneath the surface of one of South Florida’s busiest maritime hubs, Port Everglades, scientists found 10 million corals thriving in and around the main channel traversed daily by cargo and cruise ships, now threatened by a major federal dredging project.

The discovery, detailed in a new scientific analysis by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Shedd Aquarium, shows that coral populations near the port in Fort Lauderdale have persisted, and in some cases grown over the past decade, even as most reefs across Florida have collapsed from disease, coastal development and rising ocean temperatures.

“There are still a lot of corals out there, and they need to be protected,” said Ross Cunning, a research biologist at the Chicago-based Shedd Aquarium who co-authored the study.

Thousands of them are endangered staghorn corals—fast-growing reef builders that create habitat for marine life and help protect coastlines from storm surge. According to another recent study, also co-authored by Cunning, staghorn corals have all but vanished elsewhere in the region and are considered functionally extinct.

Most were wiped out in the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas during a marine heat wave in 2023 when prolonged high temperatures triggered the ninth mass coral bleaching event on Florida’s coral reef, forcing the corals to expel the algae that fuels them and turn white. For more than 40 consecutive days, ocean temperatures exceeded 85 degrees Fahrenheit, exposing reefs to heat stress two to four times greater than in all prior years on record, the study found.

In some cases, it was so hot, Cunning said, that the corals’ tissue “just started kind of melting off before they really even had a chance to bleach other places.”

Now, only small pockets of staghorn colonies remain farther north, including near Fort Lauderdale, where reefs around Port Everglades now represent one of the species’ last natural strongholds in the continental United States.

The millions of corals documented in the analysis by NOAA Fisheries and the Shedd Aquarium lie in, or near, the path of a proposed federal dredging project. The plan, known as the Port Everglades Navigation Improvements Project, is a major federal initiative, led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, aimed at deepening and widening the port’s shipping channels to accommodate newer cargo ships and bulk carriers that transport raw materials, including oil, gas, coal and grain.

If approved, federal scientists and local conservation groups warn the construction could cause unprecedented damage to corals within the channel and beyond.

“The project would result in the largest impact to coral reefs permitted in U.S. history,” Andy Strelcheck, NOAA Fisheries’ Southeast regional administrator, wrote in a letter to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, obtained by Inside Climate News.

Army Corps officials say the project is necessary to relieve mounting pressure on Florida’s already constrained ports. In an email to Inside Climate News, they said neither Port Everglades nor Port Miami alone can handle the region’s growing population and energy needs, noting that Port Everglades supplies nearly all of South Florida’s petroleum.

Still, they have acknowledged some of the risks. In their email, corps officials said the project “has the potential to impact corals both directly, in the proposed new channel, and indirectly through turbidity and sedimentation caused by construction.”

To dredge the channel, heavy machinery will be used to cut through rock and seafloor, breaking it into rubble that creates clouds of fine sediment. That material will then be suctioned up along with seawater and loaded onto large barges, known as scows, which carry a slurry of sediment, rocks and debris. Depending on where that sediment-laden water is released, it can create sediment plumes that can smother corals and possibly even trigger disease, Cunning said.

“These are precious resources,” he said. “We can’t afford to just dump dredging sediments on them.”

The project could also harm other vulnerable marine life, including endangered species such as mountainous star coral and the last known U.S. breeding populations of queen conch—a large marine snail prized for its meat and pink shell that was recently listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act after decades of overfishing and habitat loss.

“They’re actually even more sensitive than coral might be to having sediment fall onto them,” said Rachel Silverstein, a marine biologist and CEO of Miami Waterkeeper, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving South Florida’s watershed, including Biscayne Bay, the Everglades and coral reefs.

The Port Everglades expansion has been under development for more than a decade, with repeated delays due to concerns from federal scientists and conservation groups about the scale of environmental damage the dredging could cause.

In 2016, Miami Waterkeeper and partner organizations, including the Center for Biological Diversity, sued the Army Corps to halt the dredging project until the agency could demonstrate it would not harm endangered species or destroy critical coral reef habitat. The lawsuit cites violations of federal environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires agencies to fully assess environmental impacts before approving major projects.

“They have to make sure that whatever they do isn’t going to cause the species extinction and isn’t going to prevent the species from recovering to a point where we no longer need to protect it under the act,” said Elise Bennett, Florida and Caribbean director and a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “They can’t go forward with the project that’s going to jeopardize the species.”

The groups have since agreed to temporarily pause the lawsuit while the Corps conducts additional environmental studies before any dredging begins. But they continue to speak out against the proposed construction’s potential impacts on marine life.

Last fall, Miami Waterkeeper and other plaintiffs sent a letter to NOAA Fisheries objecting to the Army Corps’ request for authorization to incidentally harm more than 100 dolphins over the course of the project, including three species—the common bottlenose dolphin, Atlantic spotted dolphin and Tamanend dolphin—due to behavioral disturbance and permanent hearing loss resulting from construction activities.

“The Corps plans to use high explosives to remove rock in the Project area, creating large underwater blasts, which can harm marine mammals due to noise impacts,” the authors of the letter, including Silverstein, wrote. According to the letter, the Army Corps estimates the project would require roughly 280 blast events over its anticipated five-year duration, with construction expected to begin within the next three years.

A Lesson in History

For conservation advocates, their concern is grounded in recent history. Between 2013 and 2015, the Army Corps led a similar expansion of Port Miami.

Throughout the dredging project, Silverstein said, she went diving in the channel several times to observe how the reef was being impacted. “When I got to the bottom, I thought that I was on the sandbar. I couldn’t see any corals,” she said.

As Silverstein continued to swim, she began to see the tips of sea fans and seaweed poking out of the sediment. “Then I realized we were on the reef, but it had been buried,” she said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowConsultants hired by the Army Corps initially reported that just six corals were killed. But Silverstein said, “the impacts to corals was far greater than what was being reported.”

A 2019 study that assessed the full extent of the damage later found that more than 560,000 corals were killed during the project. “These are animals that are attached to the bottom, and they can’t move,” Cunning said. “So when they’re buried by sediment, they die.”

The analysis, co-authored by Silverstein and Cunning, also concluded that harmful impacts likely extended up to six miles beyond the immediate dredging site.

With Port Everglades supporting an even higher density of coral, scientists say they are determined to avoid a repeat of that outcome.

Cunning and a team of other scientists, including several from NOAA Fisheries, conducted a series of dives in Port Everglades in 2024 to establish a detailed baseline of coral abundance and health. The goal, Cunning said, was to capture the clearest possible picture of what exists now, before any dredging begins, to inform mitigation plans and accurately assess damage if the project moves forward.

Cunning was surprised, he said, by what they found. An estimated 10 million corals live within about a mile of the proposed dredging site. That total includes hard corals of all sizes and species, including more than 40,000 colonies listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), such as staghorn corals.

Some of them could be decades, even centuries old, said Andrew Baker, a professor of marine biology and ecology at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science and director of the school’s Coral Reef Futures Lab, where he researches coral adaptation to climate change.

It is impossible to save all 10 million corals, he said. The process would need to prioritize species already on the brink.“I think you need to go through an exercise of figuring out which corals are the most important to save,” he said. “That might include all the ESA-listed species.”

Beyond that, Baker said he would recommend focusing rescues on older, reproductively mature corals that could be used to spawn in land-based facilities and “produce new recruits that could then be used to replenish the area afterwards.”

So far, Army Corps officials say they are committed to relocating all corals larger than 3 centimeters before dredging begins and outplanting them at nearby natural reef enhancement sites and artificial reefs. Mitigation efforts of this scale, Baker said, will require careful planning well before any construction starts and years of active rescue efforts.

“The scale of that project is so massive that unless we begin it now, we’re going to just narrow the window of available time to rescue corals and not be able to get enough of them,” he said.

Even with that level of preparation, scientists caution that relocation is no guarantee.

“The fate of relocated corals is still not always great,” Cunning said. “We can’t just assume that all the corals that are relocated are going to survive.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,