Time and water are running low on the Colorado River.

Amid one of the driest winters on record, representatives from seven Western states have less than two weeks to meet an already-delayed federal deadline to find a new way to share the dwindling Colorado River—one that recognizes the megadrought and overconsumption plaguing the basin.

The current guidelines for implementing drought contingencies expire later this year, but as the Feb. 14 deadline looms, basin states, particularly Arizona and Colorado, have begun discussing the prospect of settling their disputes in court, suggesting that a deal is far from guaranteed. And while a meeting last week in Washington, D.C. between the Interior Department and all seven basin states brought some hope, state negotiators have again dug in their heels.

“I’ll certainly own whatever failure attaches [to me for] not having a seven-state agreement,” said Tom Buschatzke, the director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the state’s lead negotiator, in a meeting among the state’s stakeholders on Monday. “The only real failure for me, when I look in that mirror, is if I give away the state of Arizona’s water supply for the next several generations. That ain’t gonna happen, and I won’t see that as failure if we can’t come to a collaborative outcome. To me, that’s successfully protecting the state of Arizona.”

Those who hoped for a repeat of the winter of 2022-2023, when heavy snowfall across the West temporarily and partially replenished critical reservoirs, easing pressure on negotiators, are out of luck. With 2026’s winter about halfway over, it would take record amounts of snowfall for the Colorado River basin to climb back to merely average snowpack levels, said Eric Kuhn, the retired general manager of the Colorado River District and an author on Colorado River issues.

“People are mobilizing for potential litigation, and the question is, is somebody gonna pull a trigger?” Kuhn asked. “Hydrology may be the driving force. It may not be human action. It may be nature that forces us into litigation.”

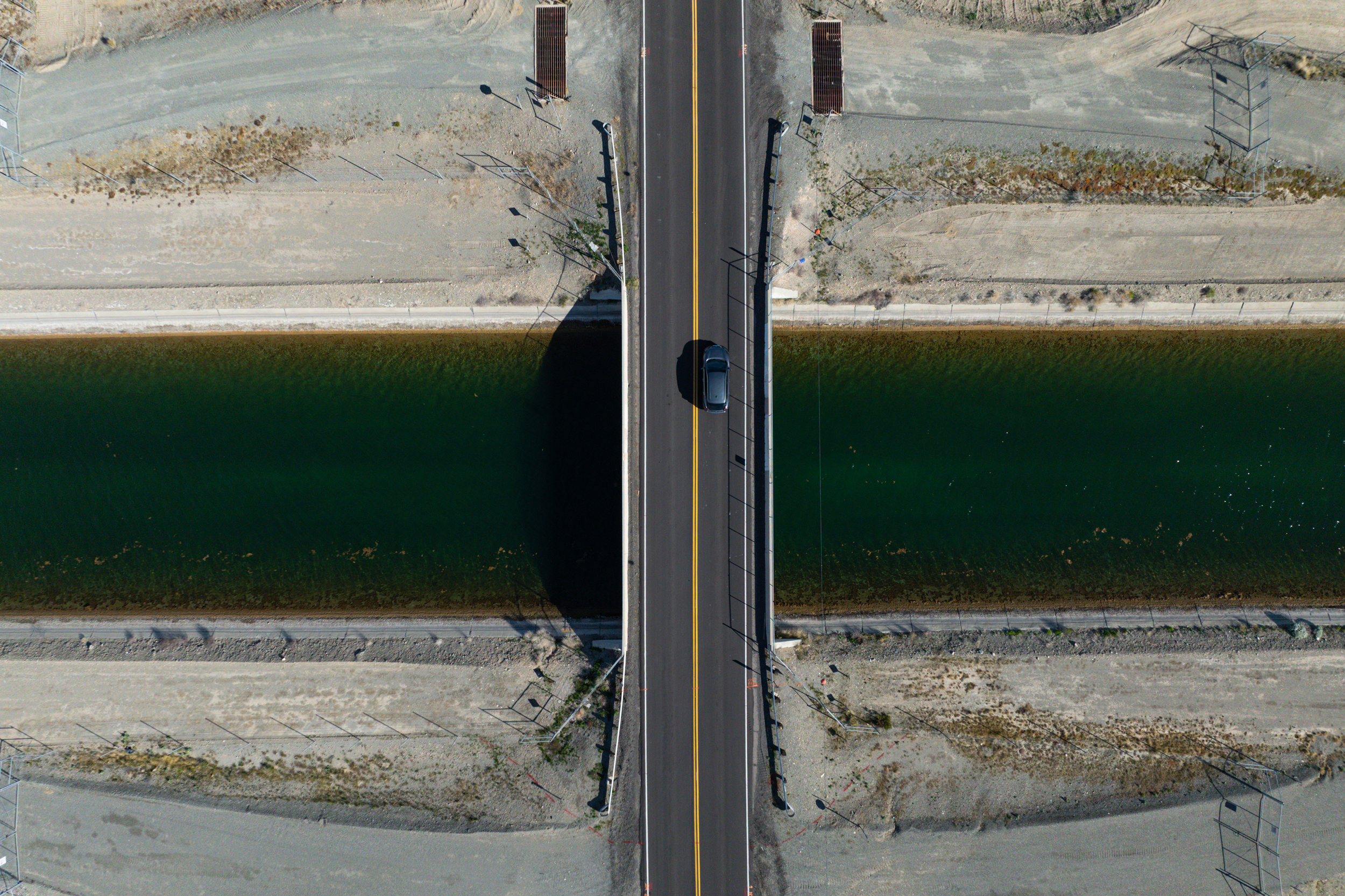

The Colorado River basin spans parts of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming, and serves over 40 million people across the seven states, 30 tribes and Mexico. It contains dozens of watersheds, all but one of which—the Green River basin in Wyoming and slivers of Colorado and Utah—have experienced below-average or well below-average precipitation since October, when the new water year begins.

A storm in mid-January, which started in the West and brought several inches of snow to eastern parts of the country, did little to alleviate the drought.

“It’s a very critical situation right now,” Kuhn said. “This is climate change at work.”

Low Water, High Pressure

Low snowpack will result in less water melting into reservoirs across the basin come spring and summer. With less water stored, the Bureau of Reclamation’s options for managing the federal infrastructure along the river, including lakes Powell and Mead, the largest reservoirs in the nation, and their respective Glen Canyon and Hoover dams, will be constrained.

The dams provide hydroelectricity for more than a million people in the Southwest, but must hold water well above the turbines that generate power. If water levels at Lake Powell dip below “minimum power pool” for an extended period of time the agency would have to bypass the turbines, turning off the electricity they produce, and deliver water to the Lower Basin through lower outlets on Glen Canyon Dam, which could compromise the structure. At that point, the Bureau of Reclamation would have to choose between damaging the second-highest concrete-arch dam in the U.S. or reducing water releases to Arizona, California and Nevada, which would be a devastating blow to the region’s cities and economy. Some experts have predicted that could happen as soon as next summer or sooner if this winter’s dry spell continues.

Last September, Kuhn and a consortium of other hydrologists and Colorado River experts authored a report that found that if the current winter was similar to last year’s, Colorado River users would overdraw the river by 3.6 million acre-feet, and there would need to be “immediate and substantial” reductions in water use across the basin to prevent a total collapse of the system. One acre-foot is enough to supply water to two to four households.

Now, with winter looking even more dismal than initially forecast, Kuhn says the Bureau of Reclamation’s options are “further constrained, unless things get wetter in the next two months.”

One option that Kuhn found likely was a big release from Flaming Gorge near the Wyoming-Utah border, the largest federally managed dam upstream of Lake Powell. He guessed the release could be anywhere from half a million to 1 million acre-feet of water.

While today’s drought and low streamflows are a product of nearly three decades of aridification, water forecasters cannot say for sure how climate change will impact future water supplies. Under some models, precipitation remains low and consistent, but rising temperatures dry out soils across the basin, leading them to absorb more snowmelt and further reduce streamflow.

Other hotter futures could also be wetter, Kuhn said, but this would not reinvigorate the river. “We’re expecting stream flows to continue their downward trend,” he said.

And if that is the case, Mother Nature may be the deciding factor between a successful negotiation and litigation.

Hydrologically speaking, we are living through a winter where “that’s a possibility,” Kuhn said. “I think it’s gotta put a lot of pressure on the states.”

Looming Litigation

A resolution in the courts is looking increasingly likely.

During her state of the state address on Jan. 12, Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs said the “Upper Basin states, led by Colorado, have chosen to dig in their heels instead of acknowledging reality” during negotiations.

The state, she said, had established a $1 million legal fund in anticipation of litigation, with a bipartisan bill introduced to add another $1 million to it. This will “keep putting Arizona first and fight for the water we are owed,” she said.

“As negotiations continue, I refuse to back down.”

A week later, Colorado lawmakers asked Becky Mitchell, the state’s lead negotiator, about its prospects in litigation. “We are gonna have the best lawyer,” she said. “We will be ready.”

Earlier in the week, Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser assured state lawmakers that he is prepared to go to court and blamed the other basin for the lack of a deal.

“The reason it’s hard to get a deal is you need two parties living in reality. And if one party is living in la la land, you’re not going to get a deal,” he said. “I’m committed to not getting a bad deal just to get a deal.”

The Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, and the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada sounded far apart on a deal at the annual Colorado River Water Users Association conference in Las Vegas last December. Some negotiators advocated for a short-term agreement while others called for greater federal pressure.

Last week, negotiators from all seven basin states met in D.C. to try to break the impasse. After the meeting, governors Spencer Cox, of Utah, and Mark Gordon, of Wyoming, said in a joint statement that “all acknowledged that a mutual agreement is preferable to prolonged litigation,” and both felt encouraged by the results of the meeting.

In a separate statement, Arizona Gov. Hobbs said she was also encouraged, and that the states “reaffirmed our joint commitment to protecting the river.” Arizona has been and remains willing to continue bringing solutions, she added, “so long as every state recognizes our shared responsibility.”

Earlier this month, the federal government released a range of alternatives outlining how it would manage the system if no deal is reached by Feb. 14. If that deadline passes without an agreement, the political and environmental situation across the basin may become as grim as the snowpack.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowArizona officials have said any of the federal government’s proposals would likely lead them to pursue litigation and that the Bureau of Reclamation’s draft Environmental Impact Statement puts all the risk of the river’s decline on the Lower Basin and does not comply with the bedrock law of the river. Under the outlined federal proposals, the vast majority of the cuts would affect Arizona, which relies heavily on the river for water but holds junior rights, often making it the first to face significant reductions. The state has already had a third of its water rights to the river cut.

“The entire weight of the river cannot fall on Arizonans, the Valley [Phoenix] and the Tucson metro areas,” said Brenda Burman, general manager of Central Arizona Project, the entity delivering Arizona’s Colorado River water, at a press conference Monday. “That’s not acceptable. We, as water managers … we will make sure that there is water flowing.”

The Lower Basin has volunteered to cut 1.5 million acre-feet, the amount of water lost to transpiration and evaporation in a year, and asked that the Upper Basin share in cuts after that amount. The Upper Basin, which has never used the full amount it is entitled to on paper, has proposed making only voluntary cuts to its use.

Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University, said she’s felt litigation is increasingly likely since the basin states missed their initial federal deadline in the fall and their negotiations began to deteriorate.

“I believe that everybody has kind of stared it down and concluded that litigation isn’t such a horrible idea that it needs to be avoided,” she said.

As a former litigator, Porter said the threat of legal action may force both sides to develop their arguments along with facts and data supporting them, which could provide the clarity needed for a settlement. But a lawsuit would extend the uncertainty surrounding the region’s water supply, Porter said, affecting the planning of cities, tribes and farmers waiting for new guidelines.

Litigation would likely focus on one of the most crucial sections in the 1922 Colorado River Compact: Article III(d).

Under this part of the agreement, the Upper Basin “will not cause the flow of the river at Lee’s Ferry,” a point just south of Glen Canyon dam, “to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years.” Should the average flow at Lee’s Ferry fall below an average of 7.5 million acre-feet, which is a possibility given current hydrological conditions, the Lower Basin could sue the Upper Basin for failing to uphold this part of the compact.

“High-Stakes Poker”

Any lawsuit would be risky.

“That language has never been interpreted by a court,” said Anne Castle, a senior fellow at the Getches-Wilkinson Center at the University of Colorado and a former assistant secretary for Water and Science at the Interior Department. “This is high-stakes poker for both basins.”

The Lower Basin would presumably argue that Article III(d) means the Upper Basin has an obligation to deliver water, so it would have to adjust its consumption to ensure the Lower Basin receives 7.5 million acre-feet annually.

But the Upper Basin could counter that Article III(d) only prohibits it from overconsuming the river and leaving less than 7.5 million acre-feet at Lee’s Ferry, and climate change is actually responsible for the meager flows. In that case, they would bear no obligation under the compact to make cuts.

Porter said the Upper Basin’s interpretation flies in the face of history. The whole reason the compact exists was the fear California would take all of the river’s water at the time, she said, because that’s where the growth was.

“It is silly to think that California would agree to a deal with the Upper Basin that said they have no responsibility to leave water for California,” she said.

For decades, the Upper Basin cited its delivery obligation to California, Arizona and Nevada to justify building a series of dams and reservoirs above Lake Powell, Porter said.

“There’s a huge amount of evidence that the Upper Basin states … needed those reservoirs upstream because they had an obligation to deliver water to the Lower Basin,” she said.

Even if Congress originally authorized Upper Basin reservoirs to help satisfy provisions in the compact, “that doesn’t tell us what those obligations actually are,” Castle said. “Fixed number obligations don’t work with a changing climate that is causing shrinking flows.”

Not every state is eager to initiate litigation. Wyoming Senior Assistant Attorney General Chris Brown appeared before state lawmakers in January and warned of the pitfalls of letting Congress or the Supreme Court dictate what happens on the river.

Still, “as a headwater state, Wyoming has a long history of zealously defending its rights to use interstate waters, and the rights of its water users,” Brown said in an email. “The Colorado River is no different.”

Tina Shields, water manager for the Imperial Irrigation District, which is California’s biggest and most senior water rights holder, said in a statement that the state continues to work on finding a consensus agreement among all the states that depend on the Colorado River, but could not comment on the status of those negotiations.

“The Colorado River hydrology is unlikely to wait for a court decision, so any speculation about litigation is premature,” she said.

Although Arizona’s Lower Basin counterparts have not touted litigation as an option, Buschatzke said he is confident they will support the state, as compliance with Article III(d) affects them too, though less severely.

And the states may not be the only entities to sue. Under a 2004 water settlement, the Gila River Indian Community receives 653,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water a year, a significant allocation. But getting that water depends on the Central Arizona Project (CAP) not getting its water allotment cut.

Any unilateral action by the Department of the Interior to reduce that flow “would, in our view, constitute a blatant violation of the United States trust responsibility to protect our CAP water as established by Congress under the Arizona Water Settlement Act,” said Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis at the Arizona meeting of water stakeholders.

While litigation may clear up some of the murkier language in the compact, Castle wasn’t sure that it is the best way forward for the river’s stakeholders—particularly since these kinds of disputes can take years to resolve.

“We might get answers to a few questions after years,” she said, “but we have a river to operate in the meantime.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Chris Brown’s position with the State of Wyoming. He is the senior assistant attorney general, not the attorney general.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,