Julissa Hernandez was at work when she saw the news, in 2024, that a young mother, Chianti Means, had jumped to her death at Niagara Falls State Park, taking her two young children, a 9-year-old and 5-month old baby, with her. When Hernandez called her dad later that day, she realized that Means was a second cousin who used to babysit her.

Hernandez feels like she often hears stories from her friends and people in the community about another person trying to commit suicide or another person dying. Hernandez and Donte West, a high school classmate, recall at least five students who died by suicide during their time at Niagara Falls High School.

“Even if the signs are there, people just excuse it, because that’s just how the people in the Falls are,” Hernandez said.

Once celebrated as the honeymoon capital of the world, Niagara Falls is now better known for its environmental and mental health challenges, with data showing higher suicide rates a growing body of research suggesting a link between these issues and local conditions.

Niagara County Health Assessment data indicate that the area has elevated air pollution levels and suicide rates higher than the state average, at 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. ZIP codes in Niagara Falls report the highest rates of youth asthma-related emergency room visits. New research correlates air pollution with mental health disorders, such as depression.

Environmental and genetic factors influence the developing brain. Researchers are still exploring exactly how air pollution impacts young minds, but several studies have found that high levels of particulate matter 2.5 microns, or PM2.5, in the air can affect brain chemistry, leading to increased aggression and a loss of emotional control. Other forms of air pollution have been linked to the development of mental health disorders such as anxiety, psychosis and neurocognitive disorders such as dementia.

Niagara County no longer has active Environmental Protection Agency Air Quality monitors for PM2.5 or NO2 and the New York Department of Environmental Conservation’s monitor list shows many Niagara sites closed before 2012. Factories such as Covanta and Goodyear still report emissions to the state and the EPA under their Title V permits, however, the reports do not reflect the air quality experienced by residents in surrounding neighborhoods. The area’s air quality is now estimated using regional models and data from neighboring counties, leaving uncertainty about what residents in Niagara Falls are actually breathing.

A study published in 2025 found 36 links between ambient air pollutants and adverse mental health disorders such as autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Psychologist John Roberts and a team from the University at Buffalo took this research one step further and examined how air pollution exposure affecting mental health might be correlated with historical redlining in several cities in New York state, including Niagara Falls.

Redlining was a structural racism practice conducted across the United States beginning in the 1930s that involved denying mortgages to residents of racial or ethnic minorities. Roberts’ study looked at the impact of ambient air pollutant levels on emergency room visits for mental disorders and how those visits varied across neighborhoods affected by redlining. Overall, they found that both PM2.5 and NO2 were elevated and significantly associated with mental health disorder-related emergency room visits in historically segregated New York state neighborhoods.

“We looked at the overall concentration levels of air pollutants across regions [in the city] and found that there were elevated levels in the redlined neighborhoods,” Roberts said. “So the discriminated neighborhoods had greater pollutants, because there’s more industry or disposal wastes there.”

That means young adults in Niagara Falls are at risk, facing the adverse health effects of intensive, concentrated industry pollution. [StoryGISMap]

In the early 1900s, engineers were drawn to the region’s potential for harnessing hydropower. This hydroelectricity enabled electrochemical processes that use electric currents to trigger chemical reactions to produce compounds such as chlorine and caustic soda, or to extract aluminum from aluminum oxide. This process made Niagara Falls home to factories that produced defensive chemicals and materials used for building atomic bombs during World War II. Radioactive slag still plagues the city years later. [Source]

It also brought companies such as Hooker Chemical, which became notorious for the Love Canal catastrophe, where leaking industrial waste from a toxic chemical dump, on which a Niagara Falls neighborhood was built, led to a landmark environmental disaster that helped spark the modern environmental movement and prompted the establishment of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980. Today, it appears history is repeating itself, only now, the federal government is removing limits and regulations on toxic emissions.

Since President Donald Trump’s second term began, his administration has moved quickly to slash EPA funding and weaken emissions standards for major industries. Congress overturned Biden administration rules regulating seven toxic air pollutants, marking the first efforts to curb the Clean Air Act since its inception.

The rollbacks threaten cities like Niagara Falls, where factories still operate near residential neighborhoods.

In 2025, the Niagara Falls City School District lost nearly $734,000 in funding to provide support services for students and families after the Trump administration cut funding for two school-based mental health grants.

That funding cut impacted the Niagara Falls Student Champion Team, a student group Hernandez and West were both a part of before they graduated. Members focus on mental health awareness and trauma-informed learning. The students meet with the office manager from the University at Buffalo’s Institute on Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care School of Social Work twice a month to learn about trauma, its causes and how to be sensitive when discussing traumatic experiences. Students also share ideas and develop strategies to support their school’s and community’s mental health efforts.

The team is still active this school year, but has scaled back its activities due to budget cuts.

With the death of another student at the beginning of the last school year, the district administration arranged for the team to present what they’ve learned to Niagara Falls’ mayor and city council in early 2025. In May, during Mental Health Awareness Month, the team also presented before the Buffalo Bills Foundation, a philanthropic arm of the NFL team that supports organizations that are committed to improving the quality of life in the Western New York region, which donated $10,000 to support trauma-informed care training.

The school district used to conduct Youth Risk Behavior Surveys, but hasn’t since 2019. The surveys found that high school students in the city of Niagara Falls reported feeling more sad or hopeless in the past year than students statewide. More than 43 percent of students reported serious difficulty concentrating, remembering or making decisions due to physical, mental or emotional problems.

In response, the Niagara Falls school district has hired 18 social workers for the district over the last seven years. Before that, there were zero. Each district school also has a family support center which offers students and their families food, clothing and services they need to set students up for success. The district also offers Say Yes Buffalo opportunities which provides students tuition and support to increase the rates of high school and post-secondary completion.

“[The surveys] showed that suicide and suicide ideation is high,” district Superintendent Mark Laurrie said. “I think that comes from a lot of people feeling hopeless. I think that poverty causes a lack of schema, and people can’t see what they can become, or what they can do, because we’re surrounded by poverty.”

Roberts added that aside from poverty, family conflict, abuse, discrimination and other social trauma as a child can create a negative cognitive schema, which changes one’s basic beliefs and values about themself and changes their capacity for feeling in control. He said environmental stressors, such as pollution and violence that are elevated in sacrifice zones, make matters more difficult.

While the district is developing more resources for students, the high school still sits across the street from some of the city’s largest polluters.

Hernandez and West describe the school as run-down and likened it to a prison. They said they felt stressed at school because when they looked out their classroom windows, all they saw were factories.

“We don’t got much going for us in terms of positivity,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez was born and raised in Niagara Falls, but she lived with family in North Carolina for eighth and ninth grade, during the COVID-19 pandemic. She noticed her skin cleared up and her asthma symptoms disappeared after she left Niagara Falls. She was able to start running again, which is something she had to give up years ago because she could never catch her breath.

Hernandez grew up participating in a wide range of sports, including softball, soccer, lacrosse, track, dance, cheerleading and gymnastics. As she got older, her asthma got worse, forcing her to gradually drop every sport. She believes the poor air quality in Niagara Falls contributed to her asthma complications.

Hernandez is now an early childhood education major at Niagara University. After graduation, she hopes to become a teacher with newly acquired trauma-informed tools to help students and educate parents and guardians. West joined the team after seeing their presentation to the Niagara Falls City Council and was interested in learning and advocating for students who don’t have safe living environments. He had an aunt and a cousin who died by suicide.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“If you’re around nothing but drama and chaos, you’re not gonna be able to focus or feel right,” West said “There is no room for somebody to get their mental state right if they don’t even know how to do it.”

Christen E. Civiletto, born and raised in the city, is now a lawyer, an environmental law adjunct professor at The University at Buffalo and author of the forthcoming book “Thundering Waters: The Toxic Legacy of Niagara Falls,” set for release in June. She has spent more than 20 years researching contamination in Niagara Falls.

“People are sick in numbers too high to ignore. Niagara Falls’ children are bearing the brunt of harm from past and ongoing pollution—these are generational harms that must be addressed before any hope of restoration in the Falls is possible,” she said.

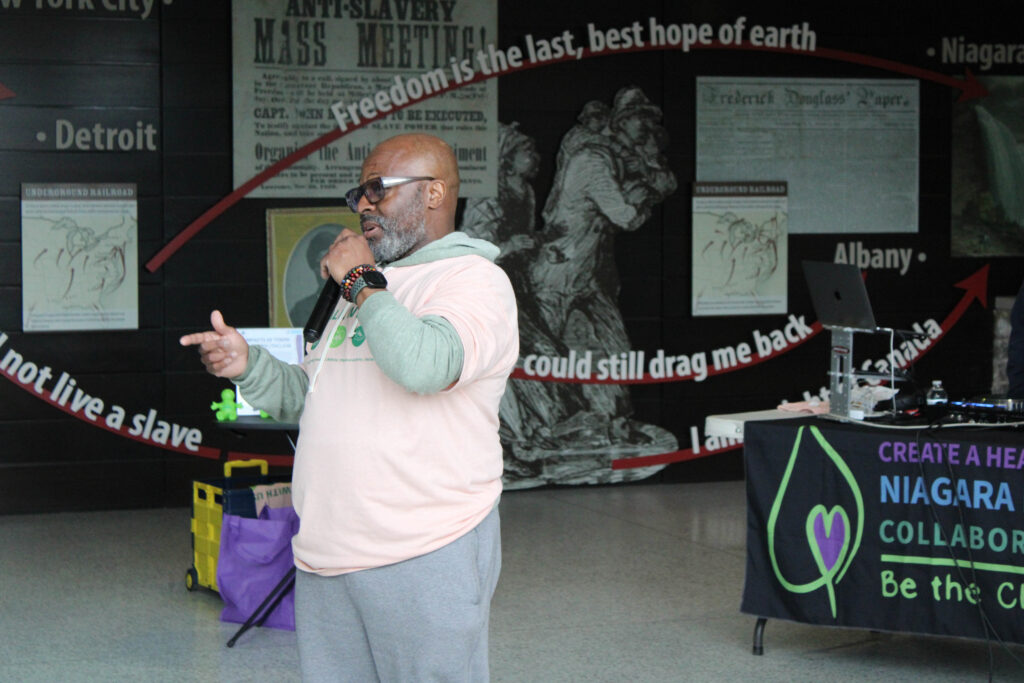

Brian Archie, a lifelong Niagara Falls resident, is tackling the city’s health epidemic from two angles. He is a current member of the Niagara Falls City Council and also serves as the executive director of the Creating a Healthier Niagara Falls Collaborative (CAHNF), which focuses on building community by improving the social determinants of health. The collaborative also educates residents about topics such as air quality and mental health.

The Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo recently awarded the collaborative $10,000 to host a youth workshop on organizing and environmental justice.

The collaborative also partners with the Buffalo Clean Air Coalition, a nonprofit that develops grassroots leaders who organize their communities to lead environmental justice and public health campaigns in western New York.

The coalition hosted three environmental justice meetings in Niagara Falls in between June and October.

Archie and the Niagara Falls City Council are teaming up with residents to develop programs and policies that aim to improve mental well-being and physical health. Last fall, Niagara Falls became a New York state Climate Smart Community, a state program that provides climate assistance to local governments.

“If I’m not working to change our city, then I’m complacent,” said Archie.

Despite the legacy of pollution and intergenerational trauma there are still these places where hope is alive and community persists. Just like the Love Canal Homeowners Association back in the 1970s, the community is fighting back.

“There’s this rule in organizing that if we can get just 3.5 percent of a population united behind a shared goal, we can make societal changes,” said Bridge Rauch, Clean Air Coalition environmental justice coordinator. “Three or four people out of 100 and you can make a lot of things happen.”

With citywide groups such as CAHNF and student-led groups such as the National Champion Team, Rauch feels like the sky’s the limit.

“Ultimately, I believe basic organizing is what will restore deep democracy and build community across movements and demographics, and allow us to tackle the issues of the 21st century,” said Rauch.

In June 2025, West sat in a half-filled auditorium for the Coalition’s first ever environmental justice meeting for Niagara Falls residents. He listened to Rauch speak about his city’s history, including the Love Canal catastrophe and asked questions, including why he wasn’t taught about the environmental threats in school.

“I don’t know why it isn’t brought up, it could literally happen again,” West said. “Trauma is passed down generation after generation, and people don’t know how to stop it.”

Reporting for this project was supported by the Pulitzer Center

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,