Wyoming’s Red Desert, a large ecosystem spread through much of the state’s central and southwestern lands, appeared undisturbed on a warm mid-September day, just the way sage grouse like it.

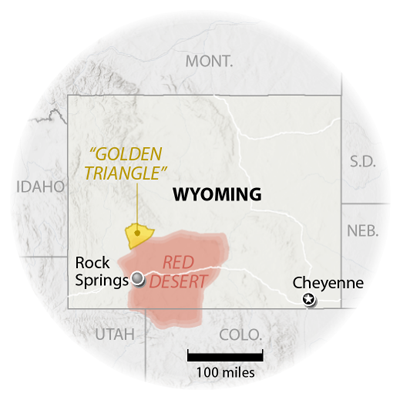

“This landscape is extremely important for sage grouse,” said Tom Christiansen, a former sage grouse coordinator with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, as he stepped to the precipice of a bluff overlooking the area’s “Golden Triangle”—so christened by Christiansen for its tremendous value to wildlife. Many of the folks assembled around him believe that critical habitat faces new threats from resource extraction.

On Oct. 1, the Trump administration announced it was amending the Rock Springs Resource Management Plan, which governs large portions of the Red Desert. Many environmentalists fear the updated document will allow more energy development in critical sage grouse habitat.

And just a month ago, the Bureau of Land Management began soliciting public comment on “significant changes” it was making to a Biden-era draft of the sage grouse habitat plan across the West, which includes the Red Desert.

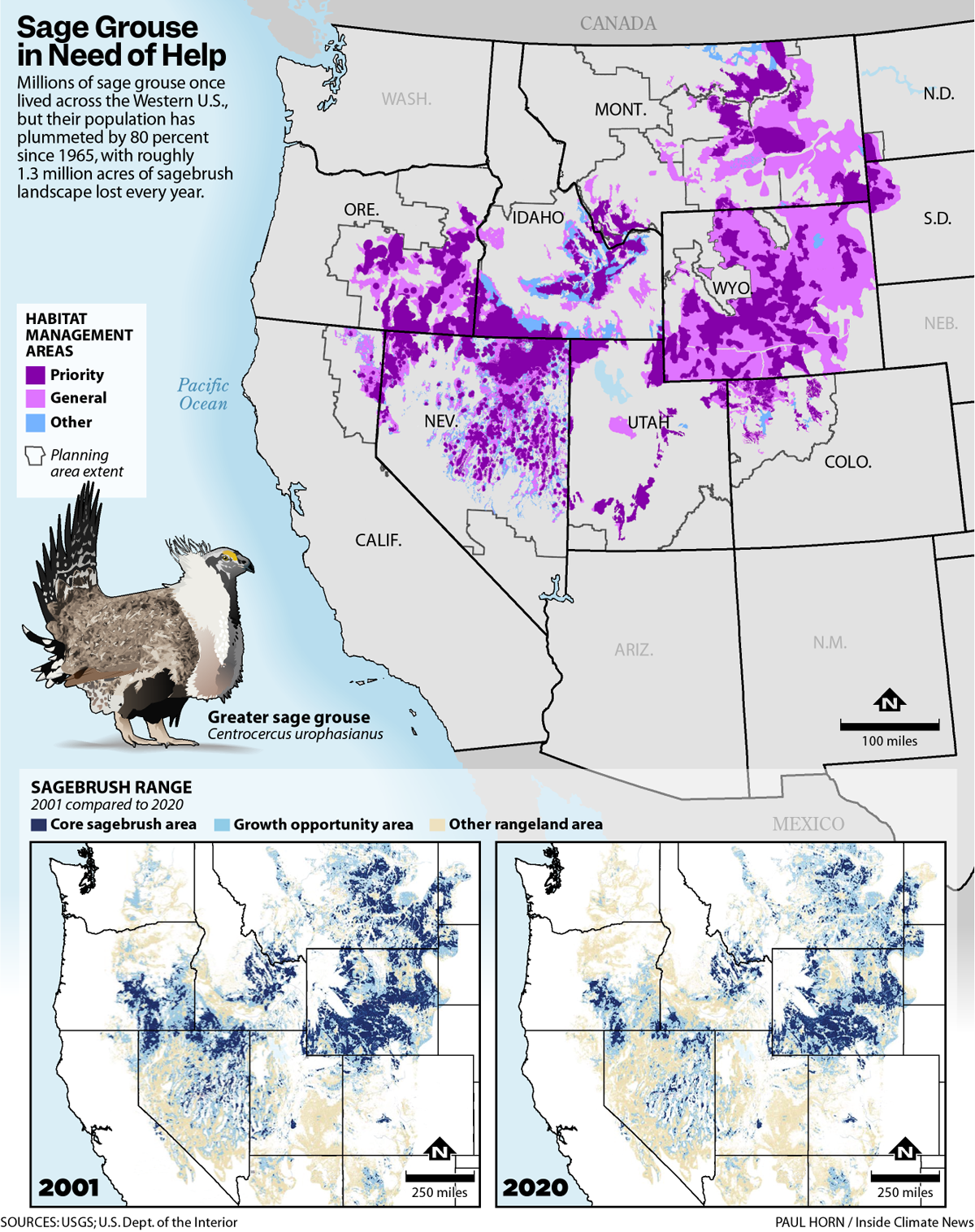

Among the most noteworthy changes was the administration’s decision to eliminate certain “priority habitat management areas” where development would have been strictly limited to protect landscapes like the Golden Triangle and its superb sage grouse habitat. The administration would instead turn the bird’s management over to the states.

The changes were welcomed by Wyoming. “I support the Trump Administration’s recognition that the Priority Habitat Management Areas with limited exceptions was nothing more than an attempt to create an onerous, unnecessary designation,” said Gov. Mark Gordon, in a statement Friday. “These designations are unneeded in Wyoming due to our state’s effective” management approach.

From 2001 to 2020, invasive grasses, wildfires and, to a lesser extent, energy development, transformed 1.3 million acres of sagebrush landscape to rangeland annually—an area more than 11-times the size of Yellowstone National Park. “That does not bode well for the future, and there’s not a lot of consideration of that fact in the new plans,” Christiansen said.

Sage grouse populations naturally fluctuate from year to year, but the overall trend has been a substantial decline in the bird’s numbers. A United State Geological Survey report published in 2021 estimated that sage grouse totals—once in the millions—have declined 80 percent since 1965, with roughly half those losses coming since 2002.

There are fewer than 800,000 sage grouse in the West today, the agency estimates.

Awash in sagebrush, much of Wyoming is classified as priority habitat for the bird, which has few other food options in the winter. The Golden Triangle is probably home to “the highest density sage grouse population anywhere on the planet,” said Meghan Riley, the wildlife program manager for the Wyoming Outdoor Council, which hosted a tour of the Red Desert for environmentalists and journalists in September.

But as climate change and a megadrought in the West intensify and lengthen the region’s fire season, the Golden Triangle may face increasing pressure from the flames and invasive species, such as cheatgrass, that often follow them.

Despite these threats, sage grouse are not recognized as an endangered species by the federal government.

The Bureau of Land Management did not respond to questions about the proposed changes to its management plan governing sage grouse habitat.

But Kathleen Sgamma, who spent decades advocating for oil and gas companies and was President Donald Trump’s initial choice to helm the BLM, applauded the revisions.

States are the “closest to the on-the-ground conditions,” said Sgamma, who pivoted after withdrawing from consideration for the BLM role to found her own consulting organization called Multiple Use Advocacy. “A federal one-size-fits-all approach is not the way to go.”

Sgamma said aspects of the Biden-era plan that “could stop all development in an area” in response to population fluctuations should have also been eliminated.

If states do become the arbiters of development in sage grouse habitat, Riley felt mostly confident that Wyoming would provide effective stewardship. The state “has been a leader in sage grouse conservation” for decades, she said, and wildlife managers in the state have good relationships with extractive industries.

But Wyoming is also one of the nation’s top fossil fuel producers, and its top producer of coal. The state’s congressional delegation has cheered and aided the Trump administration’s moves to reinvigorate coal mining, boost oil and gas drilling and scrap environmental regulations.

Those actions run counter to the state’s leadership on sage grouse conservation, Riley acknowledged, but she’s optimistic that conservation interests and energy development can strike a balance that protects critical habitats.

“My hope would be that with those good existing relationships and trusts that the state has, [state wildlife managers] will be able to negotiate with industry to make sure that they’re drilling far enough away from important places,” she said.

A state-by-state approach could also result in states going to drastically different lengths to foster resilient landscapes in the face of climate change. Behind the Golden Triangle, Christiansen noted that the jaggy peaks of the Wind River Range of mountains, which typically function as the region’s water towers over the summer, held no snow in September, an ominous harbinger of continuing drought.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowPlanning for climate change is the bedrock of a sustainable sage grouse plan, he said, and it is why there are areas of sage in the Golden Triangle that are fenced off from grazing.

“That’s a very tiny example of trying to build some climate resistance and keeping wet areas wet,” he said.

But even under Wyoming’s plan, Christiansen knows just how alluring the prospects of new energy development or more grazing opportunities can be. “It’s not out of the goodness of our heart that [the Golden Triangle is] still sage-grouse habitat,” he said. Instead, Christiansen said the area’s relatively harsh climate has kept it from being grazed or used for agriculture.

But weather factors rarely deter energy development. This May, the United States Geological Survey published a map showing “substantial” undiscovered reserves of technically recoverable oil and gas in many parts of Colorado and Wyoming, including the Golden Triangle.

Earlier that day, by air, car and foot, the group had circled the Red Desert, where they saw a herd of elk splashing through a river, several pairs of pronghorn peppering the roadside and sprawling vistas beneath remote campsites.

“I can’t think of a more ecologically significant place in Wyoming,” said Alec Underwood, conservation director for the Wyoming Outdoor Council, and one of the tour’s leaders.

“If protections aren’t warranted for that, I don’t know where they could be.”

A previous version of this story included two misspellings of Tom Christiansen’s last name.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,