This year is expected to bring a breakthrough for global climate action—and that includes the rapidly warming Arctic.

Starting in April, the United States will take over leadership of the Arctic Council, the intergovernmental body charged with coordinating the eight Arctic states: Canada; Denmark, including Greenland and the Faroe Islands; Finland; Iceland; Norway; Russia; Sweden and the United States—along with a number of observer nations, including China, India, Japan and South Korea. Though the council can’t issue policy, it provides the main forum for consensus building in the region, and produces recommendations that the delegates can bring back to their home countries.

Though the United States’ tenure is still months away, the incoming head of the council—retired Coast Guard Adm. Robert J. Papp, Jr.—has already indicated in a number of speeches that a drastic shift is coming, and that climate change will be on the council’s front burner. Papp, who spent 39 years in the Coast Guard, is Secretary of State John Kerry’s pick to represent the country as the special representative to the council. He has said that part of his job will be introducing the U.S. to the Arctic—where it has remained largely absent in policy-making—and introducing the Arctic to the U.S., where there has been a lack of awareness in both public and political spheres.

The U.S. takes the reins from Canada, which has led the council for the past two years. The theme during Canada’s leadership was “Development for the people of the North,” and during that tenure the council shifted its emphasis from environmental protection to development of the Arctic.

|

The Arctic Council: At a Glance • Founded: 1996 • Members: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States. • Mission: The council was formed as a high-level intergovernmental forum to promote cooperation, coordination and interaction among the Arctic States, including the Arctic indigenous communities. In particular, the goals include sustainable development and environmental protection in the Arctic. • How it works: The council consists of six working groups that tackle issues like Arctic contaminants, protection of the marine environment, and sustainable development. There are additional working groups for specific projects including action on black carbon and methane. • Chief Accomplishments: The council produces assessments through its working groups that are used by governments in making policy. (See examples here). It has also resulted in two legally binding agreements: a 2011 agreement on aeronautical and maritime search-and-rescue in the Arctic and a 2013 agreement on marine oil pollution preparedness and response. (Source: The Arctic Council) |

Papp won’t be walking away from Canada’s goal entirely. He has identified the improvement of living and economic conditions for the people of the Arctic as one the three goals the council will tackle under his leadership. But that will just be part of the picture. The other two goals—which Papp has been addressing in speeches and in Congress—are climate mitigation and stewardship of the Arctic Ocean.

When Papp talks about climate mitigation, he points to two main targets: black carbon and methane emissions. While reductions in carbon dioxide are central to global climate mitigation, these two pollutants may be the key for stemming the melting of the Arctic’s sea ice.

Because of carbon dioxide’s long lifespan (a century or more) even major reductions on that front may not slow the thaw of the Arctic before the ice disappears completely. But black carbon and methane are a different story. They have much shorter lifespans—black carbon’s is just days or weeks; methane’s is about 12 years—but they have a more powerful impact. Climate experts from the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization have determined that black carbon is 100 to 2,000 times more potent than carbon dioxide, while the EPA reports that methane has more than 20 times the impact of CO2 on climate change over a 100-year period.

Black carbon is produced by burning fossil fuels, biofuels and biomass (or wood-burning). In the Arctic, it comes primarily from diesel-fueled cars and trucks, household heating and cooking, agricultural burning and the flaring of unused gases at oil-and-gas wells. The U.S. accounts for 61 percent of the black carbon emissions from Arctic Council nations, predominantly from diesel transportation.

Once spewed, the dark soot of black carbon speckles the surface of the snow-covered sea ice, absorbing radiation from the sun and contributing to further warming in the Arctic (which is already warming at twice the rate of the rest of the globe) and further loss of sea ice.

Hefty reforms already under way are projected to eat away at black carbon emissions in coming decades. A report from the Arctic Council in 2011 found that black carbon emissions from Arctic nations should drop by 41 percent based on implementation of current policies alone. But climate experts say there’s more that can be done.

Methane is produced mainly through human activities—namely oil-and-gas production, agriculture and landfills. Though about 60 percent of methane emissions are manmade, there’s a secondary problem in the Arctic, where melting permafrost is creating wetlands (known as fens), which are emitting huge quantities of methane. A study from May 2014 found a spike in global methane emissions since about 2007 that can be traced, in part, to the replacement of permafrost by fens.

MORE: Meltdown: Terror at the Top of the World

It’s not entirely clear what steps the council will take to combat emissions, but Papp has indicated at least one approach to reducing black carbon. When he addressed the Center for Strategic and International Studies in September, Papp said that under U.S. leadership, the council will attempt to help promote better energy security and access to renewable energy resources in remote Arctic communities; that includes reducing the dependence on diesel generators, one of the primary emitters of black carbon.

Papp’s other goal—stewardship of the Arctic Ocean—has deep ties to climate change as well.

As the Arctic sea ice shrinks and thick, multi-year ice is being replaced by thinner annual ice, shipping channels are opening up. Already, the number of ships traversing the Arctic has increased. In 2010, just four ships passed through the Northern Sea Route. In 2011 and 2012, that number jumped to the 40s, and in 2013, 71 ships navigated the route.

That increased traffic in the Arctic Ocean brings increased environmental threat. The Arctic Ocean is the globe’s shallowest. At its deepest it reaches more than 18,000 feet; its average depth is just under 4,000 feet. That’s 10,000 feet less than the global average ocean depth. That shallow floor means there is more potential for ships to run aground and for catastrophic accidents. And should something go wrong, the icy waters have fewer bacteria to help eat up any spill—and the locations are remote, making rescue and clean-up operations more challenging.

Though it remains to be seen what steps the council will take in this new chapter, the U.S.’s turn comes amidst an unprecedented period of climate action by its own government.

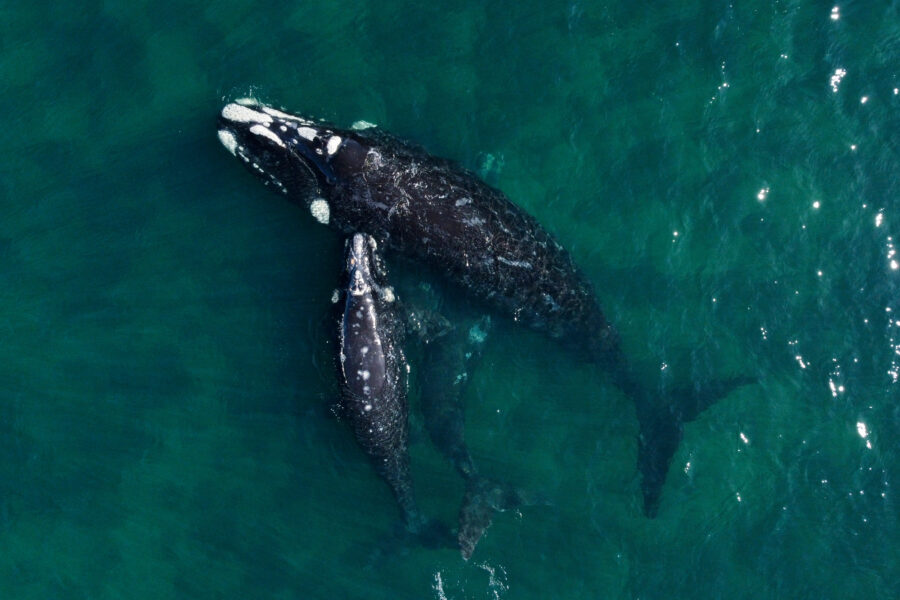

“The impact of climate change, especially sea-ice reduction, is already threatening certain species as well as the local communities that subsist on them,” Papp said in his December address to a House Committee on Foreign Affairs subcommittee. “Our goal is to protect the environment for the people who live there and to conserve the natural resources in the face of ever-expanding human activity that will surely have impacts.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,