COLD SPRING, N.Y.—Lori Moss led the way to the overlook, an elevated spot at the beginning of a steep hiking trail aptly named Breakneck Ridge. The majestic Storm Mountain dominated the landscape just across the icy Hudson River, but where Moss stood, there were rumblings from a busy roadway and a Metro-North rail station.

That’s either the sound of progress or trouble, depending on how one views this region’s galloping tourism.

Moss is a native of Cold Spring, which counts just under 2,000 residents. In the past 60 years, she has watched the once “boarded up” sleepy village transform into a place that “got really cool” for hikers and newcomers to the vast Hudson Highlands State Park Preserve.

Tourism has been an economic bounty for small businesses and hotels, Moss said. But there is a growing backlash against a proposed expansion of trails and tourist paths, the first phase of which is estimated to cost $86 million, according to 2022 paperwork filed with the New York State Senate.

Overseen by the Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail, a nonprofit group, and New York State Parks, it is projected to accommodate thousands more visitors.

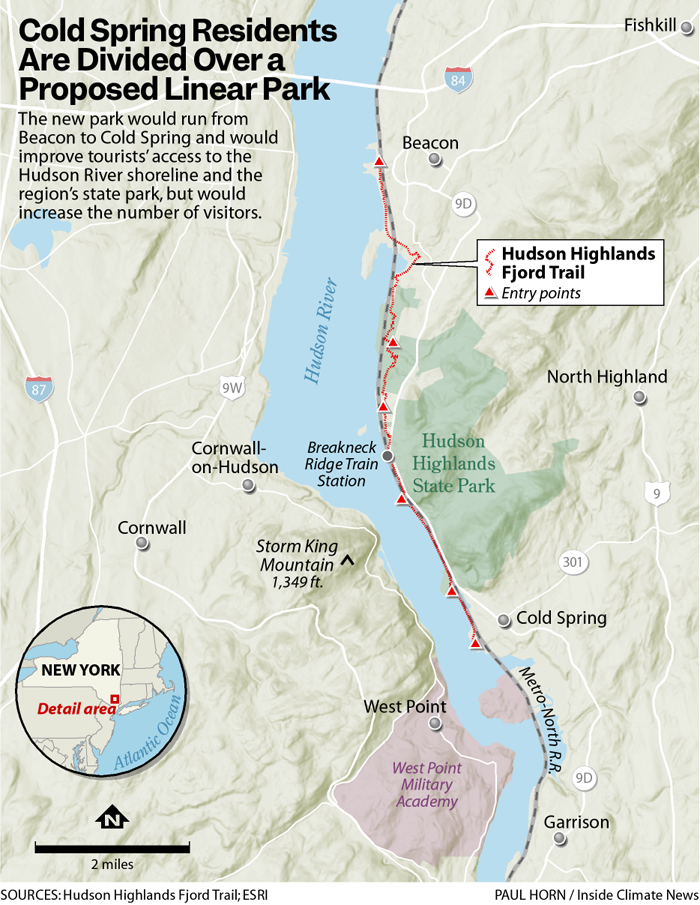

Moss, the communications manager for the Fjord Trail, hears often about how residents fear the proposed 7.5-mile linear park, which would connect Cold Spring and nearby Beacon, a city of 13,000 people north of New York City.

“By and large, I think visitation is good for the town,” said Moss as she clambered down the overlook, drawing in winter air so cold that it was hard to breathe. She had to maneuver around foot-high concrete barriers on the road next to the trail entrance, yet more evidence of the region’s appeal. The state Department of Transportation is building a pedestrian walkway with flashing lights to slow motorists and protect the increasing number of hikers.

“They stay, they dine and they shop,” Moss said. “The bad news is that real estate is out of control.”

The Fjord Trail plan, tentatively proposed to be built by 2031, would integrate existing trails between Cold Spring and Beacon with new dirt paths as well as a foot bridge over the Metro-North railway. The plan would add a two-mile boardwalk and shoreline trail, made of compacted gravel and recycled materials, along the Hudson River bank. Construction would occur in phases.

The first phase, which enjoys widespread support across the town, will break ground in the spring. It includes an upgrade at the Metro-North station at Breakneck Ridge, and a bridge that would go over the train tracks, allowing people to access the river.

The Parks Capital Fund, according to the 2022 presentation to the state Senate, has allotted $35 million for this first phase of the plan. The park fund would cover the cost of 145 parking spaces, the trail connector, new restrooms and an upgrade to the Metro-North train station, according to a written submission by Scenic Hudson.

All the other aspects of the plan still need to be approved by New York State Parks and any other concerned agencies.

New York State Parks provides stewards at the park, including five full-time staff in winter. During peak visitation season in the summer and fall, State Parks adds six employees to address the increase in hiker numbers. The agency also works closely with staff at the Fjord Trail to increase hiker safety on the trails, and will continue to do so if the plan goes through.

A study conducted by the Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail calculated that there were 444,400 visits to the region in 2023—a figure its planners derived by tracking and estimating the activities of 55,500 visitors who return to the site month after month. Visits are expected to increase annually with or without improvements, the study contends. The Fjord Trail calculated that by 2033 the region could draw between 15 to 55 percent more trekkers and visitors to its leisure destinations.

Though there are economic benefits to increased tourism, residents agree that their town cannot handle more visitors without better infrastructure. Many are concerned about disturbances to local wildlife and the spread of invasive species. They want more debate about the impact on the countryside as well as the character and feel of their small town.

“It’s Not Livable and it’s Not Sustainable”

Mayor Kathleen Foley, in an email statement to Inside Climate News, was blunt about the effect of growing tourism on townspeople who have lived for generations in and around Cold Spring.

“In our busiest seasons, residents largely avoid Main Street and the lower village because of the crowds, traffic, and garbage,” Foley said in her email. “It’s not livable and it’s not sustainable…It’s hard to feel at home in our own Village when we are swarmed by visitors.”

Foley says that the plan has sharply divided the village’s small population. The Fjord Trail, which has been in the making for two decades and is part of a public-private partnership with New York State Parks, has even given rise to a new nonprofit in opposition to it.

“The boardwalk is going to be this big attraction, and that attraction is going to draw hundreds of thousands of people,” said Dave Merandy, a board member of Protect the Highlands, a community group which was formed two years ago to block the expansion.

Though he supports many aspects of the Fjord Trail, like the refurbishment of Breakneck Ridge Station and the trails to bypass the village, he fears that some aspects of the plans will exacerbate environmental issues in the region’s parks and river.

“When you look at the impacts it’s going to have on the environment, what it’s going to do to our community, it’s like, ‘Are you willing to give all that up?’” said Merandy, who was the mayor of Cold Spring from 2015 to 2021. “My family has been here for four generations, and people have fought this whole time to preserve this area.”

Tourism in Cold Spring over the past decade has been bolstered by a number of factors, according to local residents, including internet posts and articles that have advertised the park’s qualities, and the pandemic, which attracted more people from cities.

Congestion in the village and surrounding areas is now a predictable menace. On busy days many tourists regularly park illegally on Route 9D, the roadway that transects the town and borders the Hudson River. Hikers also routinely walk along the road to the Breakneck Ridge trail as cars speed by at 55 miles or more per hour.

Kate Orff, an architect working with the Fjord Trail to design the linear park, said the plans are meant to alleviate such risks.

“If you even just walk a short segment along Breakneck, you’ll see immediately what the true dangers are,” said Orff, founder of SCAPE Landscape Architecture. “Every site visit that I’ve made, there’s some almost terrifying moment when cars and people are in very close proximity.”

Supporters of the Fjord Trail plan said critics should recognize possible benefits: The added infrastructure is designed to encourage day hikers to bypass the village. The trail modifications would add parking spots in three areas as well as a shuttle bus system to ferry passengers and provide more feeder paths from Cold Spring into the trail network. That all would help to free up its streets, supporters say.

But local residents worry that more visitors will travel to the region because of the changes, which include a wheelchair-accessible boardwalk and shoreline trail from a village park to Breakneck train station. This leg of the linear park would be a flatter and shorter walk than most trails.

Cold Spring’s mayor said the Fjord Trail plan has focused on foot traffic and cars but does not address the likely drain on public services as visitors increase.

“These services are already strained—we don’t have enough volunteers now,” Foley said in her email. “When our fire and ambulance services are in the State Park, as they already are frequently, they are not in service for our community, leaving residents vulnerable for hours and reliant on mutual aid from agencies further away.”

The Fjord Trail’s draft generic environmental impact statement, which was open for public comment until earlier this week, acknowledges the potential for increased demand on emergency services, although it discounts the impact. The trail “overall would not result in substantial change to the demand for police, fire, and medical response providers that serve the area,” according to its statement.

Debate Over the Cost to Nature

The Cold Spring area has a long history of environmental activism. In 1963, Scenic Hudson, a nonprofit advocacy organization that works to restore the Hudson and the surrounding areas, was founded to stop the development of a hydroelectric Con Edison facility on Storm King Mountain.

Through multiple lawsuits, the development of the plant was stopped in 1980. The fight is often credited as an early model for grassroots environmental activism. The Fjord Trail is a subsidiary of Scenic Hudson.

Today, critics are again raising issues about possible environmental harm as a likely result of new plans—but this time, they say, Scenic Hudson’s subsidiary is potentially causing the harm.

“Overtourism,” a term often used to refer to tourism that has an outsized impact on infrastructure and local residents, has been linked to an increased spread of invasive species on hiking trails. They can outcompete native plants, a problem on many trails in the region.

Soaring tourism can also increase trash and noise, both of which can harm wildlife. The Fjord Trail promises to address some of these issues in its draft proposal, but environmentally conscious residents say the plan flies in the face of Scenic Hudson’s legacy.

“Whenever you have a disturbance, there’s a lot of area within the park that has really nice plant communities that are invaded by non-native ones,” said Tom Lewis, founder of Trillium Invasive Species Management Inc., a company contracted to eradicate invasive species in the Fjord Trail area. “We think it’s really key to go through and rescue those plants and use them for restoration efforts throughout the rest of the trail.”

Orff, the landscape architect, said Fjord Trail is incorporating native plants into the restoration of the area, and has contracted experts like Lewis to reduce invasive species. She said critics are not considering how the plan will safeguard some of the resources they hold dear.

“There’s rainwater coming down slopes of these incredibly beautiful hills,” Orff said. “We’re working to shape the ground in a very subtle way to help capture and filter that water. It’ll be an improved hydrology system, and they’ll better distribute water across the area, and also help make micro habitats.”

Another nonprofit called Riverkeeper, which joined Scenic Hudson all those years ago to fight the Storm King power plant, has expressed opposition to aspects of the Fjord Trail, particularly the boardwalk. The boardwalk would require pilings of material, about 1,920 cubic yards of fill, to be placed in the Hudson River to support the structure.

Riverkeeper declined to comment about the Fjord Trail plan but referred to its public statement earlier this year.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe construction for the boardwalk, as well as the pilings, will disturb built-in rock that was installed on the shoreline over a century ago to protect the Metro-North railroad from daily tides. The bank has been left alone for over a century, and an ecosystem has established itself, according to the Riverkeeper statement. It adds that the construction and establishment of these new structures would “harm the river anew.”

Additionally, Riverkeeper’s statement contends that the Atlantic sturgeon, an endangered species, would be adversely impacted by these structures. According to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the species migrates through the Hudson River to spawn, and juvenile sturgeon often stay in the waters for a couple years before moving to the sea. The added parking lots are likely to introduce contaminants to the river through stormwater runoff, according to Riverkeeper.

In its environmental impact statement, the Fjord Trail said that the area impacted by the piles and boardwalk represents a “de minimis loss of potential foraging habitat for shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon when compared to the amount of similar habitat in the Hudson River.” The construction will stop from March through June to mitigate impacts on migrating fish, it said.

In an interview, Amy Kacala, the executive director of the Fjord Trail, said that the organization was still discussing ways to mitigate the impact of these structures in the river, including by adding native aquatic plant species on planted shelves on the shoreline.

The Fjord Trail’s statement acknowledges that new construction might displace or stress wildlife, particularly rare or endangered species such as peregrine falcons, eastern fence lizards and eastern box turtles. But, it said, that “would not result in the permanent loss of quality habitat for sensitive species.”

Cold Spring—a Town Divided

The Fjord Trail group’s ambitions have grown over decades. It began as a greenway committee in 2007. Nothing much came of the discussions until a master plan was released in 2015, which addressed the village’s overtourism with bicycle paths along Route 9D and potential shoreline trails near Cold Spring.

The Fjord Trail’s current plans were made official when the nonprofit was registered as a subsidiary of Scenic Hudson in 2020 and Christopher Davis, chairman of Davis Advisors, a global investment management firm, was named its chairman.

Davis is the grandson of legendary New York investment banker Shelby Cullom Davis, and a board member of his grandfather’s foundation, the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund. Since 2021, the foundation has given at least $45 million to the Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail, according to U.S. tax filings.

From 2018 to 2020, the foundation also donated $5 million to Scenic Hudson for the “Fjord Trail Project,” and another $8.7 million to the Scenic Hudson Land Trust for the Fjord Trail “including the purchase of Duchess Manor, and to the Bench Trail,” according to U.S. tax filings.

Inside Climate News reached out to Davis through his company to ask about the donations, but he did not respond.

“We are very much in a David and Goliath scenario, facing a project backed by private money, political power, and a massive PR machine,” Foley, the mayor, said in her email. “What began as a community conversation on improving trail head access nearly 20 years ago has morphed into a Robert Moses-scaled folly, masquerading as environmentalism and accessibility.”

For longtime residents and critics of the expansion, the more ambitious proposals are a departure from the region’s environmental history. Fjord Trail supporters said that they have worked to engage the local community, and have organized over 80 public meetings in that effort, but opposition persists.

Moss, the Fjord Trail communications manager, said the group just wants to face realities in an increasingly popular region. Around Cold Spring, Moss pointed out that neighbors have staked signs in their shops and yards to show their loyalties. “Fjord Forward” is one such placard, posted by supporters. Another is akin to the logo from the movie “Ghostbusters”—with “Fjord Trail” crossed out with a big red X.

“Why don’t we figure out how to mitigate and manage visitors and hikers and tourists that are coming here,” Moss said, “because they’re not going to stop coming.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,