The city’s precarious position in the face of multiple climate change-related pressures, such as coastal or rainfall flooding and extreme heat, has not been a focus of this year’s mayoral race—but perhaps it should be.

The health and expansion of green space and trees, the creation of protection against flooding and the reduction of air pollution in the city are all central to the well-being of New Yorkers, particularly those in often-overburdened low-income communities.

These are challenges New York City’s next mayor will face, but have been shaped by the current leader, Eric Adams.

New York state Assembly member Zohran Mamdani is a favorite to win the mayoral race, with former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo trailing him by a few points in the polls, and Curtis Sliwa, the Republican nominee, trailing even further behind.

Adams, who is running as an independent, has struggled to reach double digits in the polls. His tenure has been fraught with bribery charges, though he denied these and they were ultimately dropped at the request of the Trump administration. Federal prosecutors are still investigating allegations of corruption involving his aides.

Whoever wins the race will have to contend with the Adams administration’s mixed legacy on dealing with the city’s many climate-related pressures. These issues will outlive the next mayor’s term and those of the many that come after him.

On the Path to Decarbonization

In 2019, former Mayor Bill de Blasio passed Local Law 97, which established emissions limits for the city’s large buildings.

More than two-thirds of citywide emissions come from buildings—and the law encourages owners to increase their property’s energy efficiency, and eventually switch from gas to electric appliances such as induction stoves and heat pumps.

“It’s the first big law of its kind that has specific, enforceable pollution limits that drive energy efficiency upgrades, which in turn creates jobs and cuts utility bills on specific buildings,” said Pete Sikora, the climate and inequality campaigns director at New York Communities for Change.

Starting in 2024, the law places increasingly stringent limits on greenhouse gas emissions for city buildings. This past June, owners of buildings over 25,000 square feet were required to report their buildings’ 2024 emissions. However, the Adams administration has offered them a six-month reprieve if they need more time to gather data. The limits placed on their properties are relative to size and occupancy.

A study by the Urban Green Council, a nonprofit that collects data on city buildings and advocates for building decarbonization, found that only 8 percent of buildings are out of compliance with last year’s limit.

However, the 2030 and 2035 limits promise to require more drastic changes for owners, as the city races to net-zero emissions for these buildings by 2050. Some worry the cost of these changes will have an outsized impact on co-ops and condominiums owned by less wealthy New Yorkers, highlighting potential equity issues in the law’s implementation.

“The key for Local Law 97 is ensuring that we are making technical and financial assistance available for lower- and middle-income housing such as co-ops and condos,” said Alia Soomro, the deputy director for New York City policy at the New York League of Conservation Voters.

As the mayor in the lead-up to the law’s implementation, Adams is largely responsible for the rulemaking aspect of the law. In his 2023 “Getting 97 Done” plan, he expanded the NYC Accelerator program, which offers financial incentives and guidance to help building owners comply with the law. The plan also identified state and federal tax credits and incentives that could benefit property owners.

But some of Adams’ new rules and policies associated with Local Law 97 have stirred controversy. Last year, Adams announced that some of these buildings’ emissions could be offset by investing in the GreenHOUSE fund, which would help affordable housing developments decarbonize.

Though environmental groups generally support this, many have taken issue with other ways owners can offset their building’s impact on global warming, such as buying renewable energy certificates, which represent electricity generated by a renewable source, to mitigate fines. Some organizations want to place limitations on this.

Adams has also added the controversial “good faith effort” provision into the law, which offers property owners a delay in complying with emissions limits and curbs fines if they demonstrate efforts to decarbonize their buildings.

“Adams started creating loopholes in the law—using and abusing the regulatory authority that he has under it,” said Sikora, with New York Communities for Change.

In response to questions from Inside Climate News, a City Hall spokesperson wrote in an email that the administration was legally compelled to offer renewable energy certificates and an acknowledgement of “good faith effort” as a pathway for compliance with the law.

The spokesperson added that there are limitations to these aspects of the law. For example, building owners who demonstrate a “good faith effort” are prohibited from purchasing renewable energy certificates to comply with the law. When building owners are allowed to buy these certificates, the funds must be used for a project that will help power the city’s electricity grid with clean energy.

On the other side of decarbonization—renewable energy development—Adams has shown support through his rezoning plan “City of Yes for Carbon Neutrality,” which made it easier to add solar panels to city rooftops, loosened regulations that limited energy efficiency upgrades and made it easier to build small energy-storage systems in residential neighborhoods. These efforts drew widespread support from climate activists.

Protests have occurred in some areas of the city, including Staten Island, over the installation of battery storage in residential neighborhoods due to fire risks, with even the Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin weighing in. Currently, these zoning changes remain in effect.

Adams on Environmental Justice

Around 44 percent of the city’s census districts are home to environmental justice communities, according to the mayor’s office.

These residents face disproportionate amounts of pollution in their neighborhoods—often due to historic disinvestment. Power plants, waste transfer stations and last-mile warehouses—facilities that take in goods from trucks from across the country and sort them before they are transported to their final destinations—are concentrated in these areas.

As a result, these communities experience disproportionate amounts of truck traffic in their neighborhoods and the air quality is often worse compared to the rest of the city. Low-income residents and people of color are more likely to live in these areas.

In 2022, Adams consolidated multiple city agencies under the umbrella of the new Mayor’s Office for Climate and Environmental Justice, which aims to address environmental justice issues and promote sustainability and environmental remediation of city sites.

Two years later, the Environmental Justice Advisory Board, established under former mayor Bill de Blasio, released the first-ever Environmental Justice NYC report, a study of the city’s environmental inequalities.

Lonnie Portis, the director of policy and legislative affairs at WE ACT for Environmental Justice, which is based in West Harlem, said that Adams had sound policies to address environmental justice issues, but that they often relied too heavily on federal funding, which can be withdrawn at any time.

For example, grants from the Biden administration provided much of the funding for electric school buses, as well as state funding. Most of the current buses are diesel-powered vehicles, which can lead to significant pollution and health impacts for young children, particularly for those with asthma. The asthma rates in neighborhoods with more truck traffic, such as some areas of the Bronx, are higher than in other parts of the city.

According to City Hall, the city’s school bus vendors have been awarded $174 million for 533 electric school buses through the EPA’s Clean School Bus Grant and Clean Heavy-Duty Vehicles programs and New York State Energy Research and Development Agency’s Bus Incentive Program. As of August 2025, the city has 68 electric school buses in operation.

But future federal funding opportunities may not materialize as the Trump administration scales back funding for electric vehicles. These types of grants can have a particularly positive impact on environmental justice communities, which often suffer from poor air quality in their neighborhoods.

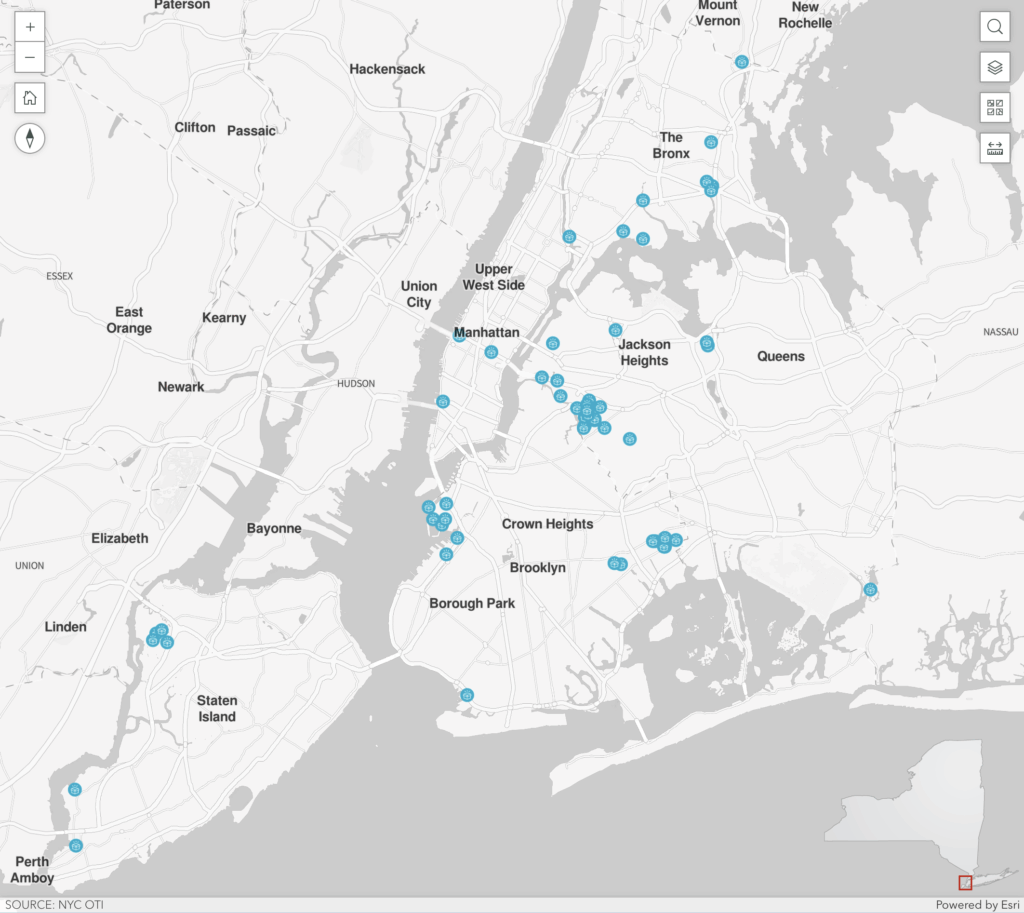

Some stormwater flooding prevention programs undertaken under Adams also rely on federal funding, such as the cloudburst hubs—cloudbursts are short, extreme rainfall events that happen more often due to climate change. These “hubs,” which are often located in environmental justice neighborhoods, use underground water basins, rain gardens and other tools to absorb and hold water during a storm.

It can also prevent water from overwhelming the sewer systems, which can lead to sewage overflows into the city’s waterways, as Inside Climate News reported last year. This program relies on funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which President Trump has gutted and threatened to dismantle completely.

The specific FEMA initiative slated to fund the cloudburst program, Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, was cut in April of this year. The future of those funds is now uncertain.

“Usually what we’re finding… is that when there’s no funding for that thing that’s related to climate or environmental justice, it just no longer becomes a priority,” said Portis. “So it kind of falls by the wayside, and no one seems to really want to do much, if anything, about it.”

WE ACT has also focused on the issue of extreme heat for vulnerable New Yorkers, particularly those living in hotter neighborhoods due to limited access to green space. The organization has advocated for a citywide policy that would require landlords to provide a way to cool tenant apartments and homes when it gets too hot.

Portis and his organization were excited to see this policy included in Adams’ “PlaNYC: Getting Sustainability Done,” which promised to address the issue by 2030. Adams has also emphasized the importance of cooling centers, which provide refuge for residents who don’t have air conditioning—especially elderly New Yorkers.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowHowever, environmental justice neighborhoods continue to experience high levels of air pollution from truck traffic. Air pollution can have more severe health impacts on days of extreme heat due to the added stress on the body to keep cool.

Adams has been trying to address the truck traffic through micro-hubs, where truck operators transfer their deliveries to smaller electric cargo bikes or electric vans—and eventually through “blue highways,” which would enable more of the city’s freight to be moved via barge.

Ultimately, the city relies heavily on truck freight to keep it moving—and a future of electric trucks is still far away.

The next mayor will also have to decide how to institute the citywide curbside composting program, which became mandatory under Adams. This year, the city began to fine people for not separating their food scraps from the rest of their garbage. In April, Adams stopped enforcing the composting mandate through fines, though his deputy mayor stressed that it was still “mandatory.”

A Piecemeal Plan for the City

To Tyler Taba, the director of resilience at the Waterfront Alliance, the Adams administration has notched some small victories, but has lacked the comprehensive vision for the city and its waterfront that he had been hoping for.

Despite small wins, including the expansion of greenways in the city, which offer residents more access to the waterfront and green spaces, Taba argues that more could have been done to understand and address the multi-pronged climate issues the city faces—such as stormwater flooding, coastal flooding and extreme heat.

A 2021 law required the city to create the Five Borough Climate Adaptation Plan to address the problems. The outcome, AdaptNYC, is an online platform that brings together existing models for the city’s climate future and often already-proposed mitigation strategies. Taba feels it fell short of its goals, especially in developing new strategies to mitigate the impact of issues such as flooding in specific neighborhoods.

“I think what we want to see is a much more proactive [approach],” said Taba. “The city laying out the foundation for—here’s where we’re going to make investments, here’s the timeline, and here’s the way we’re going to engage communities to make sure that the plans are tailored to the needs of each community.”

The city does engage community members through Adams’ project “Climate Strong Communities,” though both Portis and Taba feel it’s not enough.

According to City Hall, the program is working to determine which climate projects would best serve these communities, including heat mitigation projects, such as green roofs and street trees. It then pairs those projects with available funding opportunities and existing work.

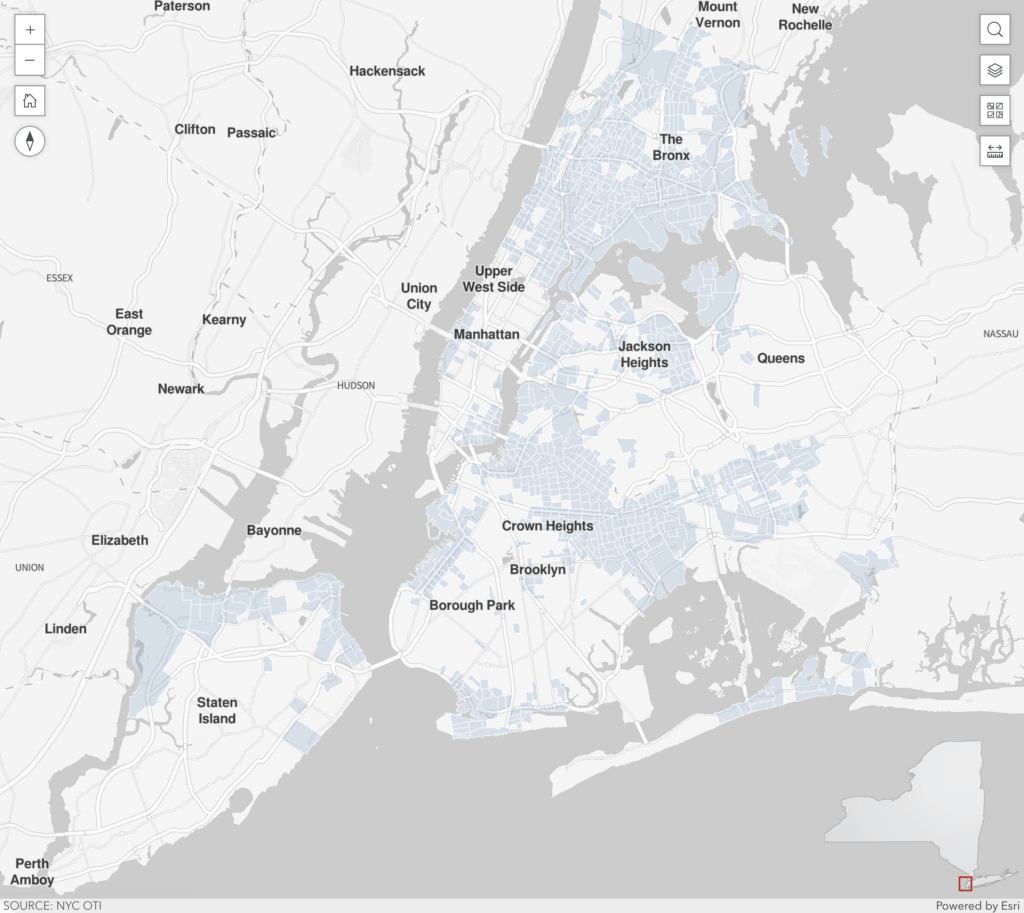

The Adams administration continues to focus on attempting to reduce stormwater flooding in neighborhoods—even if it is done piecemeal, as Inside Climate News reported last year.

Under Adams, city agencies have undertaken a variety of projects across the five boroughs to mitigate stormwater flooding through the use of green infrastructure, such as street trees, plant beds and green roofs, and gray infrastructure, including expanding the sewer system in some areas and large underground basins that can hold in rainwater to avoid overwhelming the sewer system. According to City Hall, the administration has spent over $1.5 billion on these initiatives.

The issue of protecting the city against coastal flooding has been a joint project between the city, state and federal governments. Work has already begun on protecting the east portion of lower Manhattan using floodwalls.

“From day one, the Adams administration has put forward bold strategies and solutions to address the impacts of climate change and reduce the city’s carbon footprint—and will continue to do so,” a spokesperson for City Hall wrote in an email.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,