VICTORIA FALLS, Zimbabwe—On a bright and clear day, Gillian T. Davies reached the end of a winding dirt track where armed guards waited.

The ecologist from Massachusetts was attending an international conference on wetlands that would influence the future of the world’s fastest-disappearing ecosystems. The sessions were not going well.

So, on the conference’s break day, Davies hired a local guide and headed deep into the African bush to find one of the threatened species that frequent the wetlands she’s fighting for.

The guards, clad with AK-47-style rifles slung over their shoulders, were a round-the-clock team protecting a crash of white rhinoceroses from poachers. Davies felt a surge of gratitude for the men, but wondered: What had her species become that such a thing was necessary?

The scene was a visceral echo of what she saw playing out at the conference, a meeting of the parties to the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, one of the oldest environmental protection treaties. Despite governments’ vows to protect them, one-fifth of Earth’s wetlands have been destroyed. Of what remains, a quarter are in ecological distress. Few people know either of those facts or why they matter.

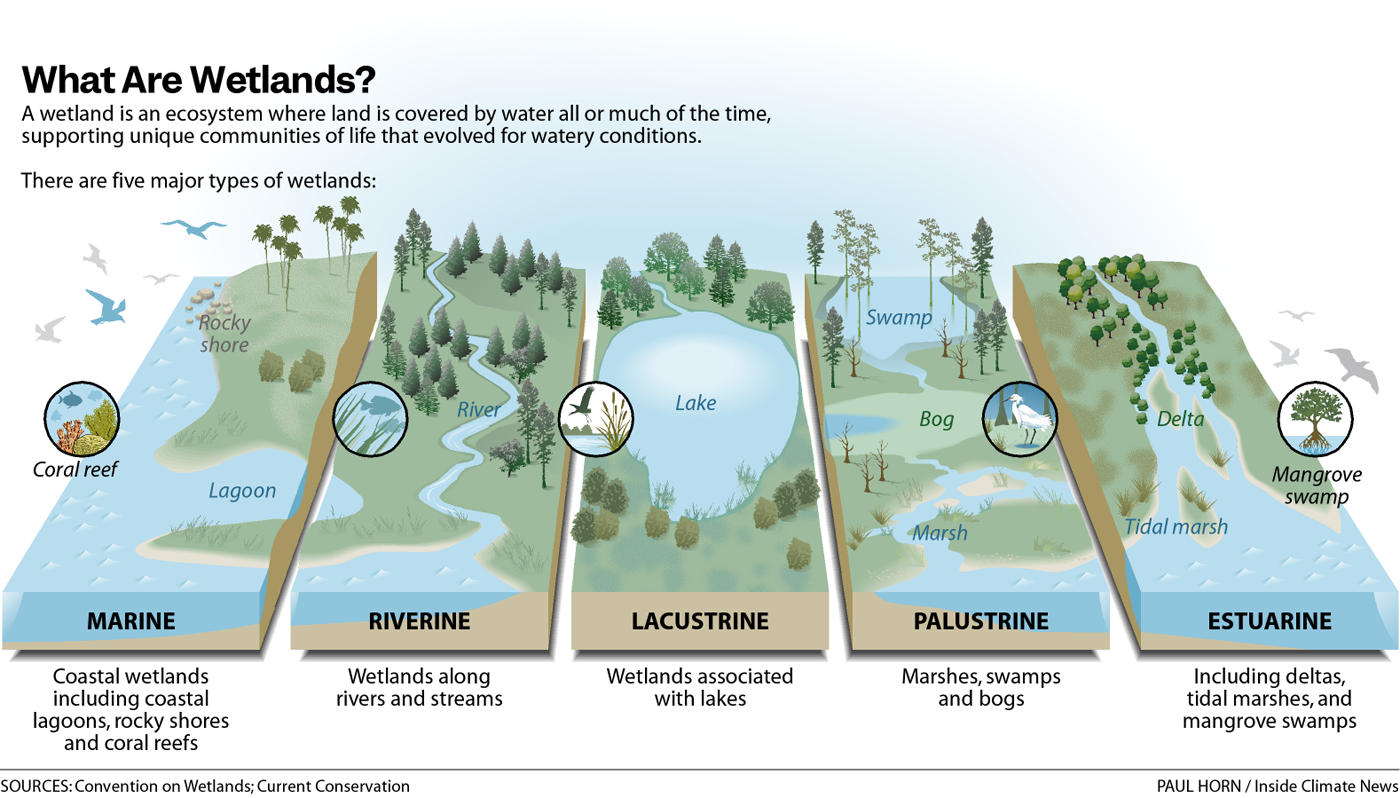

Vilified in the past as wastelands, the watery ecosystems are in fact a linchpin of planetary stability, with their moist soils sequestering more carbon dioxide per unit than forests. With unmatched efficiency, they act as Earth’s kidneys, filtering pollution and recharging drinking water sources while preventing storm damage and flooding. For scores of communities, wetlands are a cradle of culture, a source of sustenance and a home.

Publicly, Davies has been part of the cacophony of scientists sounding increasingly dire alarms about the accelerating pace of wetland loss. Privately, she came to believe something more was needed. Existing laws, she thought, aren’t enough: Humans are driving life on Earth to a perilous place.

So, she came to the conference in July with ambitious plans. Wetlands, she would argue, should have the highest form of protection the law provides: rights.

Davies is one of a growing number of Western scientists joining the rights of nature movement, helping to advance laws recognizing that ecosystems possess inherent legal rights because nature has intrinsic value.

Led by Indigenous peoples, the rights of nature movement has grown dramatically over the last two decades, from constitutional protections in Ecuador to national legislation and court rulings in Spain, New Zealand, Panama, India and beyond.

As scientists have flocked to the movement in recent years, they’ve given it a new layer of credibility—and enforceability. They’re helping to craft laws rooted in scientific principles, collaborating with local communities to collect evidence for court cases and drawing on fields like ecology and neuroscience to provide a scientific basis for the movement’s core philosophies, ideas that Indigenous peoples have already validated through centuries of territorial stewardship.

Still, Davies’ push for wetlands’ rights is one of the movement’s biggest challenges yet. Unlike forests, wetlands are widely misunderstood and overlooked, even among the environmentally conscious.

For now, though, as Davies pushed through a thicket of shrubs with the guards’ assent, the only thing on her mind was what might lie on the other side. And there they were, five magnificent white rhinoceroses, their thick, soft bodies resting in the dappled shade.

Standing in their presence, Davies simply watched the slow, rhythmic breathing of the napping creatures, feeling a mixture of awe for what remained and sorrow for what was being lost. This profound paradox is what fueled her. Soon, she would have to channel that resolve back into the work ahead.

The Draining of the Fens

For centuries, humans have assaulted wetlands, a destructive impulse that began with the Roman empire, spread to the Dutch in the 15th century and then to England. There, a consortium of wealthy landowners and King Charles I embarked on one of the world’s earliest ecocides.

England’s fens, a type of peat marsh stretching over hundreds of thousands of acres, provided flood protection and freshwater to rural inhabitants and habitat to countless species. The landowners and king, however, saw them through a different lens. They drained the fens to convert wetland to profitable farmland, a move they saw as a triumph of human engineering and a way to civilize the locals into taxpaying farmers.

But as historian Eric H. Ash detailed in his book, “The Draining of the Fens,” this monumental undertaking unleashed a torrent of unintended consequences. The exposed peat soil shrank, causing the land to sink and worsening flooding. Species disappeared. And the forcible separation of people from their lands caused chaos that fed the tensions leading to the English Civil War.

According to rights of nature advocates, the draining of the fens was more than a misguided engineering project. It was an act fueled by a flawed ideology that still motivates decisions today.

In the advocates’ telling, with the rise of factories and cities, humans began to see themselves as separate from, and superior to, the rest of the natural world. Ecosystems became collections of resources, and the rise of Western science ushered in an approach to studying nature that involved breaking it down into smaller components. Earth came to be viewed as a machine with interacting parts.

This worldview was institutionalized in legal systems. Property rights gave landowners the authority to clear-cut forests, drain wetlands and mine mountains, viewing these acts as productive use of land. Animals were classified as chattel, like furniture and tools.

In this system, the law didn’t protect ecosystems, it protected the right of owners to exploit them.

New technologies, a booming human population and globalizing economies demanded more land for farming, industry and urban development. Wetlands, more than any other ecosystem, have paid the price, disappearing three times faster than forests, even as their critical importance to planetary and human wellbeing became clear.

As countries gathered in Ramsar, Iran, in 1971 to adopt the Wetlands Convention, U.S. President Richard Nixon was urging Congress to take a new approach to land use. He stressed the critical role wetlands play in flood control and the survival of fish and wildlife, calling them “some of the most beautiful areas left on the continent.” Nixon declared that a “new maturity is giving rise to a land ethic” that acknowledges how improper land use “affects the public interest and limits the choices that we and our descendants will have.”

Even so, the U.S. government continued allowing oil and gas companies to dredge thousands of miles of Gulf Coast wetlands, permitting the draining of the Everglades for development and converting wetlands in California’s Central Valley to industrial farmland.

As those habitats have disappeared, so too have the species reliant on them: 84 percent of all freshwater species have declined in population since 1970, while others, from the tiny dragonfly to the mighty Florida panther, are now threatened.

About half of U.S. wetlands have been destroyed since the nation’s founding. Developing countries are now following the precedent set by wealthy, industrialized countries around the world, razing, filling and polluting the watery ecosystems at alarming rates.

Ecological Thinking

In 1991, as Saddam Hussein was draining the Mesopotamian Marshes to punish their inhabitants for rising up after the U.S. military invasion, Davies was embarking on her first field work as a wetlands ecologist in Massachusetts.

With measuring tape, an auger, a shovel and some elbow grease, she learned she could unravel the vivid narrative of a wetland’s history through its soil. Each layer provided her with insights into shifts in plant life and land use, while changes in soil color—including surprising hues like blues, greens and oranges—could show saturation changes or evidence of a nutrient-rich past.

She learned that soil couldn’t be understood in isolation; it was in constant, dynamic interplay with every other part of the wetland.

Soil density dictates water flow. Plants pull nutrients from the soil and return them when they decompose, while anaerobic microbes remove excess nitrogen, acting as a natural filter. Vast mycorrhizal fungi networks course through the soil, serving as a nutrient highway for plants. The soil itself is a universe of life—a refuge for insects and worms that supports all the plants and animals above it. Each wetland is itself part of an even larger web of interactions unfolding across the planet.

Davies’ decades of wetland and soil ecology work fundamentally undermined the idea that “humans stand apart from all else on Earth,” she said.

While many scientific fields are focused on taking things apart, ecology is focused on connections and relationships, mirroring the thinking of Indigenous knowledge systems and philosophies that are the rights of nature movement’s inspiration. All show that humans are part of nature, interdependent with everything in it.

So, when Davies stumbled upon the rights of nature movement in 2019, the idea didn’t surprise her. She considered that living ecosystems were far more like humans than inanimate objects like ships or entities like corporations—both of which have legal rights.

“It made logical sense,” she said.

Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous knowledge systems, also referred to as Traditional Indigenous Knowledge, are time-tested bodies of information accumulated over centuries or millennia of living in close connection with an ecosystem, and contain deep understanding of the natural world.

Indigenous knowledge systems typically intersect with a people’s spiritual and cultural identity and philosophies, often centering on the belief that all life is interconnected and that humans have responsibilities to land, water, animals and other parts of the Earth for long-term wellbeing.

At the time, Davies was researching declarations that had changed the course of history, hoping to write something similar about wetlands’ importance to the global climate. But as she read through the Declaration of Independence and Universal Declaration of Human Rights, she came across one she’d never heard of: the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth.

The document described Earth as “a living community of interrelated and interdependent beings,” and outlined rights to protect its “vital cycles” and functions. This, she thought, was an accurate reflection of reality.

Davies was nervous about bringing up the topic later that year at a meeting of wetlands scientists, a group trained to build incrementally on existing methodologies and paradigms. But after she made her case, she was stunned by the reaction.

“People,” she recalled, “absolutely loved it.”

A Bolt of Clarity

In the room that day was Nick Davidson, a British zoologist and former deputy secretary general of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. He had retired in 2014 and is disillusioned with humanity’s inability to stop wetland loss. “The bottom line,” he said, “is that we have failed.”

In Davidson’s view, the problem was twofold: Governments consistently prioritize short-term profit over long-term environmental health, and humanity suffers from a deep-seated arrogance.

“The idea that we can control everything, that engineering will fix it, is a widespread attitude,” he explained in a recent interview.

Davies’ talk hit him like a lightning bolt of clarity. To Davidson, rights of nature seemed to be a much more equitable approach that removes humans as the central focus while safeguarding people’s ability to thrive in the future. “We could bring scientific evidence to support the idea,” he added.

Davies struck a nerve with other scientists in the room by underscoring a truth they all knew: Their data-based warnings were consistently ignored. She pointed to the 1992 “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity,” when hundreds of scientists cautioned that “Human beings and the natural world are on a collision course.”

Since then, humans have shattered planetary boundaries on greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use, chemical pollution and ecosystem destruction. Crossing these limits means the Earth may no longer be within safe operating space for human life.

“Are we doing enough?” Davies had asked the other wetlands scientists.

Humans—mostly via industrialized nations—are responsible for a stupefying amount of ecological harm. Humanity has ushered in an era of mass extinction, with a chilling result: Today, only 4 percent of Earth’s mammals are wild. The other 96 percent are humans and our livestock. Homo sapiens’ consumption is so voracious that it would take 1.8 Earths to sustain it.

Humans have razed one-third of Earth’s forests, damned two-thirds of its rivers and contaminated the planet so extensively that chemical pollution can be found even in the most remote parts of the Arctic and the Amazon rainforest, and in us.

If Earth’s history were compressed into a calendar year, humans would show up around 11:30 p.m. on Dec. 31. The industrial revolution, when humans’ reshaping of the planet began in earnest, would have begun in just the last two seconds before midnight.

“Any of us who do anything related to planetary operations are aware of how we’re absolutely jeopardizing the functionality of the planet that sustains us now,” said William Moomaw, a chemist and climatologist who also listened to Davies’ pitch in 2019.

Moomaw, a lead author of five Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, including the 2007 report that shared the Nobel Peace Prize, worked with Davies and others to write a 2020 proposal for a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Wetlands. Those rights—including to exist and to be free from pollution—are based on scientific knowledge about what wetlands need to persist.

When Moomaw began his career in the 1960s, the environmental movement was in its infancy. He counseled U.S. lawmakers on the first legislation to eliminate ozone-depleting substances. He can still recall the excitement of that era and how he had thought those early successes would translate into lasting progress.

“I was naive in many ways,” Moomaw said in a recent interview.

Now he sees existing environmental laws as essential but ultimately insufficient. While they have successfully mitigated some harms, he said, they still regard nature as a resource to be exploited, leaving them vulnerable to political shifts.

For Moomaw and other scientists interviewed for this article, the second Trump administration’s sweeping attacks on environmental protections and scientific expertise, and the public’s acquiescence, are deeply painful to witness.

“Most of the human population has lost contact with the fundamentals of life around it,” said Colin (Max) Finlayson, a wetland ecologist for more than 50 years. Finlayson was also in the room for Davies’ speech. Her words, he recalled, “resonated instantly.”

The rights of nature approach is, for Finlayson, a way to establish a powerful ethical shift, and crucially, one that could apply science to the law in a way that learns from past mistakes. And there are a lot of missteps to draw lessons from. “Learning,” he said, “is difficult for people who think they know it all.”

The Method

Back in the Wetlands Convention’s main meeting hall in July, Davies slipped on a pair of black headphones, turning the dial to the English translation channel. Politics were not her forte, but she had a job to do.

Seated behind a placard for the Society of Wetland Scientists, Davies and her colleague, British eco-hydrologist Matthew Simpson, took notes for the organization and whispered to each other about what could only be described as the unraveling of the conference.

The Russian delegate announced his country’s withdrawal, enraged by Ukraine’s request to monitor wetlands damaged by Russian attacks. Two empty seats marked the absence of the U.S. delegation, which either snubbed the conference or simply forgot about it; a representative showed up later to demand that any references to climate change and other concepts the Trump administration disagrees with be deleted from summit documents. And China, the most influential nation present, firmly opposed any budget increase despite showcasing its own conservation achievements with a massive delegation and pavilion.

Simpson, whose silver laptop bore a “Rights of Wetlands” sticker, was drawn to the movement because of its alignment with Indigenous peoples and local communities. Simpson had long believed those groups held more answers to environmental problems than politicians ever would.

It was a lesson he learned early in his career in Guyana’s Amazon rainforest. Tasked with assessing the impact of illegal mining, he realized that data he would have spent years collecting could be gathered in minutes by simply listening to residents—people who had lived in harmony with their lands for centuries.

“That first trip completely changed my view on how to do my job,” Simpson recalled.

For the next 25 years, Simpson built a career on reciprocal partnerships with people who, he says, already live in a way that honors the rights of nature. Simpson contributes his technical expertise while his partners apply their deep local knowledge to solve problems.

Together, Simpson and Davies have used this model to form such knowledge-sharing partnerships globally to advance rights of wetlands principles.

In Ecuador, the Kichwa people of Sarayaku—a leader in the global rights of nature movement—shared with scientists their “Declaration of the Living Forest,” or “Kawsak Sacha,” a codification of ancestral knowledge and wisdom recognizing their forest-wetland territory as a conscious, living and intelligent being with rights.

The people of Sarayaku know that the forest communicates with itself through a network that is similar to a spiderweb, explained José Gualinga, a Sarayaku leader and intellectual architect of the declaration. The life of Saryaku is also connected to that network, “as an embryo is connected to its mother—if this umbilical cord is cut, life dies,” he said.

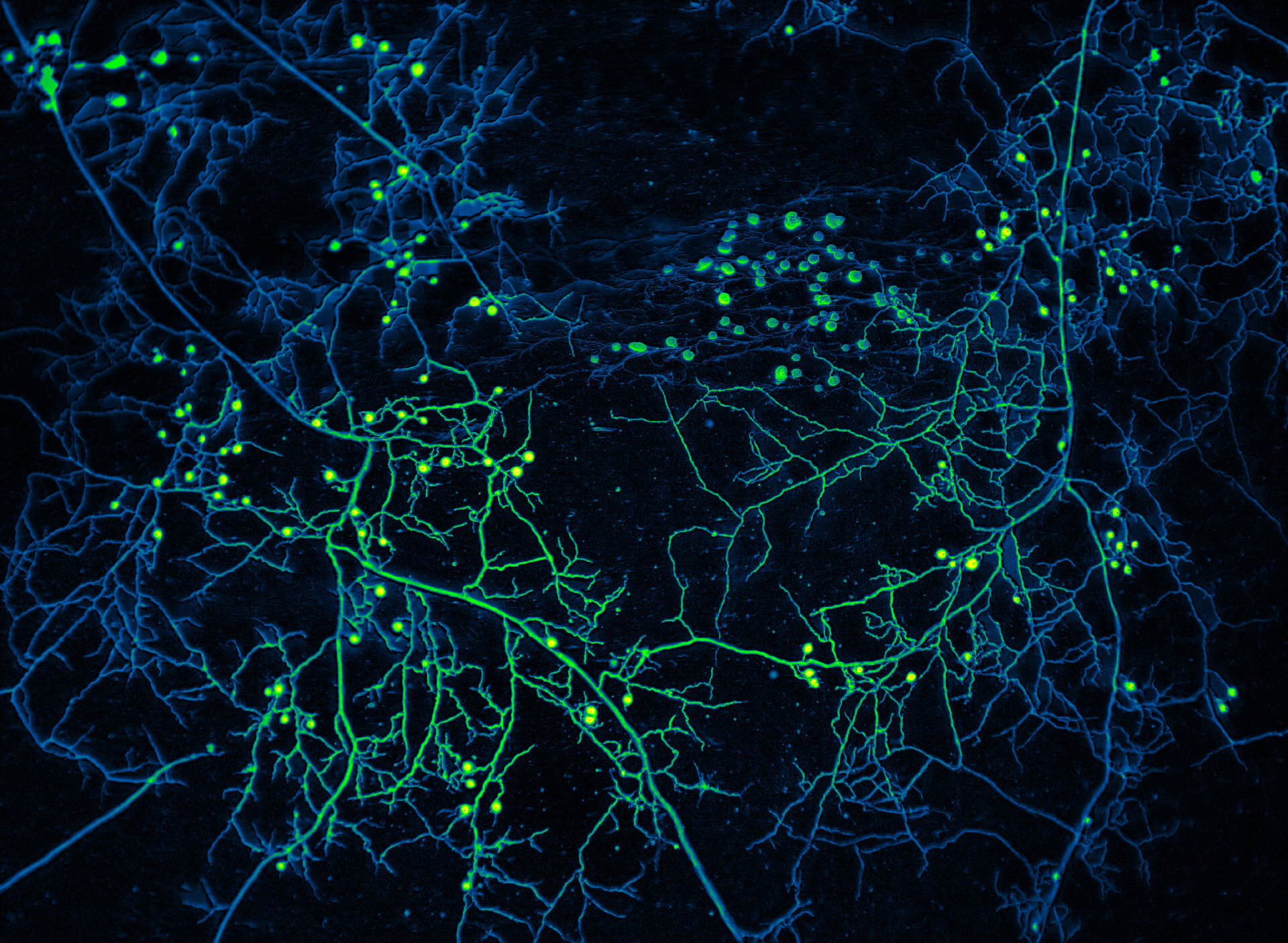

The scientists then wrote a joint declaration with Sarayaku’s leaders, annotated with studies backing up the community’s understanding of nature, including research showing that trees communicate and share resources through vast, underground fungal networks resembling human neural networks.

Older “Mother Trees” act as communication hubs, sending warnings about dangers to other trees in the community and sharing nutrients. These behaviors, the scientists’ write-up said, show that forests exhibit hallmarks of intelligence, resilience and self-organization similar to human societies.

“Kawsak Sacha is built on the philosophy and wisdom that other protective beings are alive and intelligent, including the lagoons, the trees, the swamps and the waterfalls,” Gualinga said.

Kawsak Sacha is also a way of life and a means to peacefully defend it and address global environmental crises, he added.

Sarayaku’s leaders sought out partnerships with scientists, including Davies and Simpson, as well as with academics and lawyers to help the Western world understand the validity of Kawsak Sacha rather than seeing it as a myth, Gualinga said.

The community was key in cementing the rights of nature into Ecuador’s 2008 constitution. Using that legal protection, nature has prevailed over mining companies and polluting industries in dozens of lawsuits there. Sarayaku’s leaders are supporting Indigenous communities in other countries to take similar steps. And their partnerships with Western scientists are leading to breakthroughs in understanding more-than-human life.

As climatologist Moomaw noted, the way the Saryaku peoples’ knowledge is passed down is not so different from his own practice. “In science, we say Isaac Newton was my intellectual ancestor,” he said. “Wise people from the past have passed knowledge onto us in the present—that’s the method.”

Moomaw added: “You can’t argue with outcomes, and they’ve done … a better job of managing their environment than we have in managing ours.”

“Everything Is Linked”

From the main meeting hall, Davies and Simpson strode past rows of government booths to a hotel conference room, ready to make their case for wetlands’ rights to a broader audience.

As the two scientists stepped to the front of the room, a slide appeared on a screen behind them, projecting a simple question for the 75-or-so people gathered there: “Why Do We Need Rights of Nature in Wetlands?”

A key aim of their talk was showing how the rights of wetlands are being practically applied outside the courtroom. As an example, Simpson played a video made by a community in Kenya’s Tana River Delta. The video, which highlighted residents’ sustainable use of mangroves and their efforts to reforest damaged areas, was part of the scientists’ rights of wetlands project that included Sarayaku.

In Guyana, people have been coming together once a month for a “self-help” day where they take a group action aimed at protecting wetlands. In Sri Lanka’s capital city, Colombo, locals organized to remove waste from urban wetlands. Some communities had never heard of wetlands’ rights, though they live by its principles, while others, like Sarayaku, were leading the way.

Manjula Amararathna, Sri Lanka’s director of protected area management, rose to speak about how his country has been leaning into a national policy on the rights of wetlands, and is sponsoring a Convention on Wetlands resolution encouraging governments to recognize wetlands’ rights.

“This isn’t something really new for us,” Amararathna said.

The island nation has a deep history of ecocentric thinking dating back as early as 247 B.C., when there is record of a Buddhist sermon alluding to non-human beings’ right to live. The country’s ancient, wetland-based civilization centered on networks of man-made and natural waterways. Today, some communities continue to pay tribute to rivers for sustaining human life and confer monastic status on trees.

“Wetlands are not just soil and water,” Amararathna said. “They are the life of our people, their culture. Everything is linked with these wetlands.”

Ritesh Kumar, director of Wetlands International South Asia, told the crowd that many traditional communities don’t have a “mechanistic” definition of wetlands. Instead, they understand these ecosystems through their cultural and belief systems and don’t pollute or unsustainably harvest because they know that doing so will ultimately harm themselves.

For Kumar, who also advises the Indian government on wetland policy, bringing science together with communities’ traditional knowledge improves our understanding of the world. “The reality is that science has to be integrated. Everyone has their tools,” he said.

“The rights of nature,” he added, “is not fundamentally just about laws.”

The Power of Capital

While the rights of nature movement has advanced across continents, industrialized nations like the United States have remained formidable obstacles.

This is where scientists can make a difference, said Craig Kauffman, a professor of political science at the University of Oregon and a leading rights of nature scholar.

Kauffman founded the Eco Jurisprudence Monitor in 2022 to track rights of nature developments. Analyzing more than 450 examples worldwide, he found a major commonality: They all treat nature, whether a river, forest or individual species, as part of a larger web of life.

In cultures around the world that have maintained a close connection to the Earth, especially in Indigenous communities, that way of thinking comes naturally, making it easier for rights of nature laws to take root. But what about the United States, where most people are disconnected from their ancestral histories and the ecosystems where they live?

“I asked myself what source of knowledge in Western culture embraced that way of thinking,” Kauffman said.

There was a clear answer: ecological science. He sees scientists like Davies as key to expanding the movement in places like the United States.

“The idea is that it gives the laws a greater sense of legitimacy, especially in societies like ours that traditionally value science,” Kauffman said.

Simply saying nature has legal personhood, as some legislation has done, isn’t enough, Kauffman argues. He thinks the movement should embrace examples set by Panama’s 2022 national rights of nature law and its 2023 national rights of sea turtles law, which incorporates scientific findings, like data from the tagging and mapping of turtles, to define those rights.

Marine biologist Callie Veelenturf was instrumental in that effort, making evidence-based arguments to lawmakers and helping to incorporate scientific principles into the laws. Now, she’s working to duplicate her success, rolling out a partnership with the National Geographic Society to fund conservation projects that use scientific data to advance rights of nature laws. She and Kauffman are also working on a series of academic papers about scientists’ role in the movement.

Some fields, including neuroscience, have shattered industrial-era beliefs that animals function as machines, and that their cries of pain are merely mechanical reactions. Great apes and elephants have complex social relationships and self-awareness, whales grieve for their dead, pigs assist distressed brethren, Mimosa pudica plants display learning capabilities and the list goes on. All of this gives lawyers new tools to argue that what they are defending isn’t an object, or thing, but living beings with their own interests.

“If you look at legal systems, they’re the exact opposite, they’re about human exceptionalism,” said Kai Huschke, executive director of the U.S.-based Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund and Davies’ and Simpson’s partner on wetlands’ rights.

“What I’ve witnessed from Gillian, Matt and other scientists is that they’re not just pushing a legal shift, but a cultural one as well,” he added.

Scientists are also pioneering ways to gather evidence for rights of nature lawsuits.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowBritish ecologist Mika Peck is at the forefront of that effort. Peck, an emeritus professor of ecology at the University of Sussex, co-founded Ecoforensic, an organization that trains local communities how to gather evidence to support rights of nature lawsuits.

The organization is a direct response to a landmark rights of nature victory in Ecuador. In 2021, Los Cedros, a cloud forest, defeated a mining consortium on the strength of scientific evidence showing that mining operations would endanger the forest’s “life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes,” a constitutionally protected right.

That constitutional provision, rewritten in 2008 with strong influence from the country’s Indigenous movement, echoes core tenants of ecological science.

Ecoforensic is modeled on bringing together science and place-based knowledge to build robust bodies of evidence through a new academic discipline called “Ecological Forensics” that can be drawn on when threats arise. “Paraecologists” are trained to map endangered and endemic species, for instance, and then that information is fed to lawyers.

This process is carried out over months and years, a thorough accounting that contrasts sharply with the limited environmental assessments done by companies in a few weeks. Paraecologist work, Peck says, provides a far more complete picture of an ecosystem’s health and so should carry greater weight in court.

The program has already proved successful. In 2023, paraecologists helped another cloud forest defeat a mining company seeking to operate in Ecuador’s Intag Valley.

“The year after the ruling, the mining company abandoned the site,” Peck said. “The power of removing that—the power of capital to impose its will to extract—was mind-blowing to me.”

Nature’s God

On the last day of the conference, in late July, governments quietly announced a new plan to reverse global wetland loss.

Their vision: “A world living in harmony with nature,” with governments acknowledging that “wise use” of wetlands goes beyond extracting from them. It includes, they said, “human-wetland relationships,” “traditional knowledge” and “Indigenous ways of knowing.”

It was a step forward, but governments left the critical question of how to actualize those words for another day. Sri Lanka’s resolution encouraging governments to recognize wetlands’ rights had been rejected before the conference even began, with some countries fearful it could impose some type of legal obligation on them. Amararathna said it would not and that his government would reintroduce a revised text soon.

Simpson, the eco-hydrologist, saw the summit’s outcome as a sign that politics had once again interfered with meaningful progress. He, Davies and other rights of wetlands activists now face even longer odds, and have less time.

Before leaving Zimbabwe, Simpson visited Victoria Falls, a wetland world wonder. Known to locals as Mosi-oa-Tunya, or “The Smoke That Thunders,” the falls are the lifeblood of the region, where families and groups of schoolchildren stand in awe, packs of warthogs roam and bright butterflies flit through verdant forest.

Wearing a rented purple poncho, Simpson planted himself in the falls’ dense, soaking mist. The sheer force of the falling water was breathtaking, as were the rainbows dancing in the billowing spray. But Simpson couldn’t help watching the other visitors, too, wanting to see how they were connecting with the falls.

For him, that immediate, personal bond is the first step toward seeing nature as more than an object—seeing it as worthy of reverence. The real challenge, he said, is getting people to connect with the nature around them on a daily basis, from their backyards to urban green spaces.

Now, watching a family of warthogs waddle through the forest with sovereign disregard for the humans watching them, Simpson’s resolve solidified: fighting for wetlands felt lighter knowing more and more people were resurrecting relationships with nature. Their forces were growing.

Back in town, Davies was tossing birding and wildlife books into her suitcase, already thinking about next steps. Part of that was countering people who have tried to discredit the rights of nature movement as “unscientific mysticism.”

Davies kept a running list of rebuttals in her notebook. Lately she had examined a memo, written by conservative Wisconsin lawmakers, asserting that rights are something given by God.

“Our Constitution and founding documents,” it said, “affirm that rights are inherent to people ‘endowed by their Creator,’ not to plants, rivers, or landscapes.”

The memorandum didn’t mention that Wisconsin law gives corporations and other non-human entities extensive legal rights.

The Wisconsin memo also did not mention something Davies caught while reading the Declaration of Independence: The first paragraph mentions “Nature’s God.”

“What did they mean by ‘Nature’s God’”? asked Davies, who is the great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Charles Willson Peale, a scientist, naturalist and artist who fought in the American Revolution alongside his friend, George Washington.

“Why,” Davies wondered, “didn’t they just say ‘God’?”

For her, the wording implies that God is subsidiary to Nature.

“And,” Davies said, “who is She?”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,