This article was originally published by Public Health Watch, a nonprofit investigative news organization. Find out more at publichealthwatch.org.

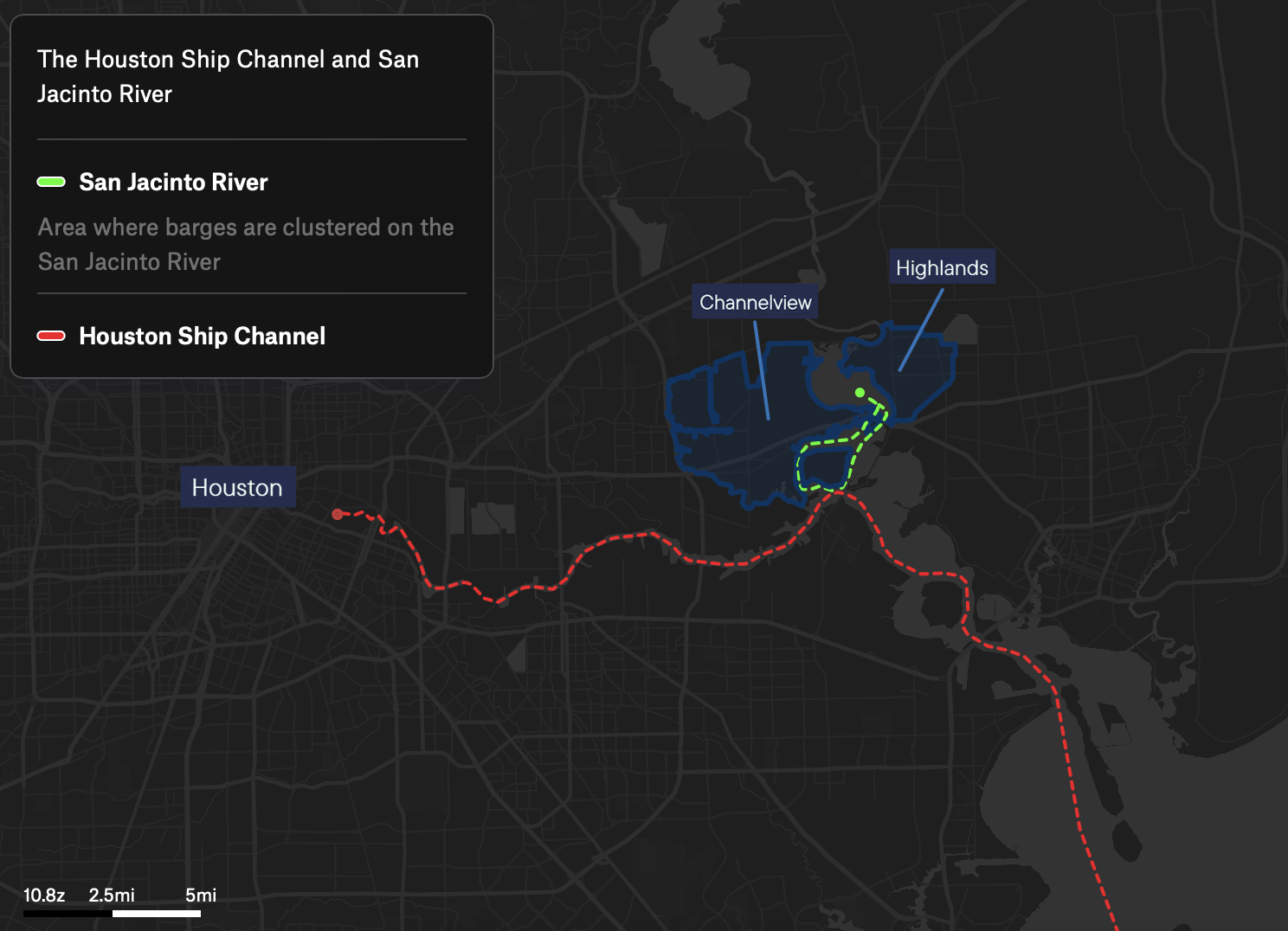

SAN JACINTO RIVER, Texas—Over the past 30 years, federal and state agencies in Texas have allowed hundreds of oil and chemical barges to amass in a once-tranquil section of the San Jacinto River, just east of Houston.

Only about 100 barges were on the six-mile stretch of water in 1990, according to a Public Health Watch analysis of archival satellite imagery. Today, at least 600 crowd the narrow waterway.

For Houston’s refineries, chemical plants and pipeline terminals, the long, lumbering cargo ships are indispensable. They keep products moving on the adjoining Houston Ship Channel, one of the nation’s busiest shipping lanes and largest distribution centers for the chemicals used to make plastics and other everyday items.

But for the 54,000 residents of Channelview and Highlands—the two Harris County communities that border the San Jacinto River—the growing industry represents danger, not prosperity.

Air quality in their unincorporated neighborhoods ranks near or at the bottom of indexes nationwide. Although the problem is usually blamed on the hundreds of industrial facilities that line the Ship Channel, data from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, shows the barges contributed more pollution in 2023 than a major Exxon Mobil facility.

The TCEQ estimated that the loading and unloading of barges and other small vessels released 5.1 million pounds of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, into Harris County that year. That’s 28 percent more than Texas’ largest VOC emitter—Exxon’s 3,400-acre refining and petrochemical complex on the county’s eastern edge—released over the same time.

VOCs include benzene, toluene and other highly combustible substances that can cause blood, kidney and liver cancers. In parts of Highlands, the average cancer risk from toxic chemicals is almost double the national average. In parts of Channelview, the risk is more than triple, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s 2020 Air Toxics Screening Assessment.

A TCEQ spokesperson downplayed the barge emissions problem, saying that barges were responsible for just 2.6 percent of all the VOCs released into Harris County in 2023.

But Public Health Watch has found major gaps in the TCEQ’s triennial emissions inventory, from which the 2.6 percent figure is drawn.

Unlike facilities that release pollution on land, barges aren’t required to obtain air pollution permits or report their emissions. The TCEQ inventory relies on data that’s self-reported by the industrial sites where barges are loaded and unloaded, not from direct monitoring of the barges themselves.

Perhaps more important, the inventory doesn’t include the chemicals barges release when they’re travelling or moored on the water. No state or federal agency gathers that information, even though experts say those emissions can be substantial.

Fumes can escape from cracks in the barges’ vapor recovery systems and from open hatches and relief valves. If pressure builds up in the barges’ chemical storage tanks, fumes are purposely vented, so the tanks don’t rupture or, worst case, explode.

“Anytime you’re transferring these volatile chemicals or gases, you’re gonna have some leakage,” said Frank Parker, a retired barge industry consultant. “It’s impossible not to have something.”

Parker said the industry is well aware that it’s largely unregulated.

“Once they’re away from the dock, nobody’s looking over your shoulders,” he said. “The maritime industry is pretty much behind [in regulation] than everyone else.”

Tim Doty, a former TCEQ scientist who spent more than a decade monitoring emissions along the river and Ship Channel, said the TCEQ has known about the barge problem since at least 2005. That’s when the agency began doing helicopter flyover studies of emissions in the area.

“It wouldn’t shock me if that [the 2023 estimate] is underestimated by a magnitude or more,” he said. “There’s kind of a hole in the regulations, so to speak.”

Doty said his mobile monitoring team sometimes took boats onto the river to record barge emissions. They’d wear respirators to avoid breathing the fumes while they worked.

Although the team submitted dozens of technical reports detailing barge pollution, Doty said the TCEQ still hadn’t dealt with the issue when he retired in 2018.

“It’s still an emission source that is, you know, generally uncontrolled and that the TCEQ doesn’t have a good handle on,” he said.

Public Health Watch asked the TCEQ if its current policies do enough to protect residents from barge emissions.

A spokesperson said in an email that “TCEQ continues to use various tools and strategies to evaluate compliance in the area and address non-compliance when identified.”

A History of Disasters

The barges pose other, more tangible threats to people who live along the river.

Barges docked in the northern part of the San Jacinto must pass by an underwater Superfund site that’s laced with dioxin, a chemical linked to lung and blood cancers. They also have to squeeze between the pillars that support the low-slung Interstate 10 bridge.

With so many barges on the river, what happens, residents ask, if some of them break loose during one of the area’s many hurricanes and floods and cause the I-10 bridge to collapse? Or crash into the Superfund site and release dioxin, plus their own loads of toxic chemicals, into the river?

“It’s not safe, it’s not healthy,” said Channelview resident Jennie Ramsey, whose family has lived near the river for three generations. “Big money has taken over and they act like it’s not a residential area.”

The quiet spots where Ramsey’s family and friends once fished and water skied are now lined with industrial docks and chemical storage tanks. A barge facility sits down the street from her house. Foul odors often surround her when she looks out on the river from her front porch.

“We’re living with these terrible possibilities and we were never acknowledged,” she said. “They didn’t ask for our input; it just happened. We’re sitting ducks now. We have a fear of an explosion. We have the fear of, say, if a flood were to come … the barges drifting across our land for acres.”

Ramsey’s fears are based on experience.

In 1994, during flooding from Hurricane Rosa, residents saw a runaway barge slam into an underground pipeline. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of gasoline poured out and set the river on fire.

In 1997, a barge company accidentally dug into a portion of the Superfund site as it was dredging the river. According to court documents, dioxin leaked into the water for years, unbeknownst to residents and regulators.

In 2019, 11 barges broke loose during Tropical Storm Imelda. One landed on top of the Superfund site, also known as the San Jacinto Waste Pits. Several crashed into the I-10 bridge, damaging its support columns so badly that the bridge was shut down for days, causing hours-long traffic jams into Houston.

The Texas Department of Transportation tacitly acknowledged the growing risk in 2023, when it announced plans to rebuild the I-10 bridge. The barge clearing is going to be raised and widened, the agency said, “due to repeated barge traffic collisions with the bridge structures.”

Construction is scheduled to begin in 2027.

The Multi-Billion-Dollar Shipping Lane

Most Texas politicians are reluctant to criticize—or even discuss—the dangers the influx of barges poses to residents. The Houston Ship Channel, which is owned and run by the Port of Houston, helps the port generate $439 billion per year, or 20 percent of the state’s gross domestic product.

Barges are the Ship Channel’s silent workhorses. Parker, the retired consultant, calls them “the 18-wheelers of the water.”

“They’re an integral part of the industry,” he said. “If you took them away, it would cripple the system, at least for some time.”

According to Parker and other experts Public Health Watch interviewed, a single barge can make half a dozen, or more, trips each day. According to a Port of Houston memo released in 2020, barges account for roughly 90 percent of all vessel traffic on the Ship Channel.

Those numbers will likely grow, because the Ship Channel keeps expanding. The port is in the process of deepening and widening the 52-mile-long waterway to accommodate bigger ships, and 17 petrochemical plants are poised to be built or expanded near its banks, according to the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project’s Oil & Gas Watch.

Harris County Commissioner Adrian Garcia, a Democrat who represents parts of Channelview and Highlands, sees the barge industry’s growth as a sign of progress.

“Let me just give a shout-out to the barge companies,” Garcia told Public Health Watch. “When I see barge activity and the growth of barges in the area, it just says our industry is still strong and it’s growing and they’re needed there.”

Garcia said he’d like barges to use cleaner technology, but “in the meantime, you know, I can’t regulate industry.”

County Commissioner Tom Ramsey, who also represents the area, is more cautious in his support.

Ramsey, a Republican who is not related to Jennie Ramsey, worked for decades as an engineer for companies along the Ship Channel. He knows how valuable Houston’s industry is to Texas and the U.S. economy. But he also knows a looming disaster when he sees one.

“I like economic development … but it ought to be done with an understanding of what the impacts are,” Ramsey said. “When you put barge traffic north of I-10, knowing you’ve got a Superfund site, knowing that the bridge is probably lower than you would feel comfortable with … well, you just have created a catastrophe.”

The Powerful Port of Houston

Residents have little say in the push of barges into their neighborhoods.

Channelview and Highlands are unincorporated, so they don’t have mayors or city councils to advocate on their behalf. And the state and federal agencies that have varying degrees of authority over the river don’t make it easy for residents to be heard.

“Time after time, we have agency after agency pointing their fingers at another agency, and it’s like, does anybody actually understand this?” said Jackie Medcalf, who grew up in Highlands and founded the Houston-based advocacy group Texas Health and Environment Alliance, or THEA. “It’s just crazy. … People who live along the San Jacinto River simply want to know what agency to call if there’s a barge loose north of Interstate 10. … If they have a complaint, who cares?”

It took Public Health Watch months to figure out which agency is responsible for what.

The most powerful agency, by far, is the Port of Houston, which owns the submerged land beneath the waterway. The port decides which companies will be allowed to rent space on the river to park, or “fleet,” their barges. It also has the power to create “barge fleeting exclusion zones” that keep barges out of sensitive areas.

Most of the port’s work is done outside the public eye and then finalized by its seven-member Board of Commissioners.

Barge lease applications don’t become public until they appear on a list of items scheduled for approval at a commissioners’ meeting. The agendas for those meetings aren’t usually posted until two to six days beforehand, so community members must keep scanning the port’s website to see if a barge lease is up for a vote. If residents miss the decisive meeting, they’ve missed their only opportunity to comment.

When Public Health Watch asked the port about its barge approval process, a spokesperson said the agency promotes transparency and openness.

“Community feedback is welcome,” the spokesperson said in an email. “The public’s input truly matters to us.”

A Missed Opportunity

In May, the port did something residents have long asked for: The commissioners voted to exclude barges from seven areas.

Five are in the Ship Channel, along swaths of residential land in the city of Baytown, where Port Commissioner Stephen DonCarlos once served as mayor. Two are in the last section of the San Jacinto River that’s still free of barges.

No restrictions were added near the I-10 bridge or the Superfund site, where barges pose the greatest threat.

Asked why those areas weren’t protected, the port spokesperson said the exclusion zones were “created primarily to safeguard sight lines for nearby residential communities and navigation on the Houston Ship Channel. There are no residential areas in the vicinity of the San Jacinto Waste Pits.”

Medcalf, the former Highlands resident, called the port’s assessment of her old neighborhood “nonsense.”

“It’s the same old narrative that we have had to fight for so long,” she said. “Get off the freeway, look around. … You have residential properties on both sides of the river at I-10. I mean, sure, it’s not what it once was. … The community has certainly broken down over the years, but there are still people who call that place home.”

Longtime Channelview resident Carolyn Stone lives about two and a half miles from the Superfund site and just yards from the river. She fears that with so many barges now crowded onto the San Jacinto, an accident like the 1994 river fire or the barge pile-up beneath the I-10 bridge in 2019 will devastate what’s left of her neighborhood.

“Until we have something that, you know, blows up and destroys all the surrounding area, they’re going to continue embedding [barges] in there,” she said. “We’re in a major flood zone, yet this is a safe area to put floating chemical storage facilities?”

In 2019, Stone founded the Channelview Health and Improvement Coalition, or CHIC, to advocate for cleaner air and water. She believes people in unincorporated communities like hers are “totally disregarded,” even though they, like all Harris County landowners, pay property taxes to the port. They’re taxed at the same rate as industrial facilities: $0.0059 per $100 valuation. The revenue—roughly $38 million countywide in 2024—is used to fund docks, wharves, container facilities and dredging projects along the Ship Channel.

“You’re decreasing home values and raising our medical costs. And we’re paying you to do that?” Stone said. “I don’t care if it’s a penny. It’s too much. We should not be paying someone to make us sick.”

In a written statement to Public Health Watch, the port spokesperson said the taxes “contribute to job creation and economic development for the region, state and nation.”

“The Everyday Person … Is Ignored”

The federal Army Corps of Engineers is also a powerful player on the river. It gives companies the permits they need to dredge and build docks, piers and other structures.

The Corps notifies the public when a company applies for a “standard” permit. It must also conduct a formal environmental analysis and give residents an opportunity to comment.

But another permit, known as a “letter of permission,” bypasses these requirements. According to the agency’s website, these fast-tracked permits are reserved for projects where the “proposed work would be minor,” “encounter no appreciable opposition” and “would not have significant individual or cumulative impacts on environmental values.”

But those parameters seem to be flexible.

In 2016, Holtmar Land LLC began trying to get a permit to build the infrastructure it needed to install a new fleet of barges about a mile from the Superfund site.

It withdrew its first application after the Corps questioned the project’s design. Two years later Holtmar reduced the project’s size – from a little over four acres to three and a half – and applied for a letter of permission. The Corps flagged that application, too, so three days later Holtmar applied for a standard permit.

This time the Corps had to notify the public about Holtmar’s plans, and residents and advocacy groups pushed back hard. The company withdrew its application just 20 days into a 30-day public comment period.

In 2021, Holtmar reduced the size of the project to two and a half acres and applied again for a letter of permission. Although the Corps wasn’t required to notify the general public, word of the application spread quickly. Residents sent more than 500 letters of opposition, and Holtmar withdrew that application, too.

In 2023, Holtmar tried again. This time Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee was among those who wrote to the Corps. He warned that installing more barges in the vulnerable northern half of the river could cause a “catastrophic release of dioxin waste” from the Superfund site and “increase the risk of damage to the I-10 bridge.” It could also “magnify negative health effects associated with emissions.” Menefee has since resigned to run for Congress.

Despite Menefee’s objections, and residents’ calls for a public hearing, the Corps gave Holtmar a letter of permission in April 2024.

An agency spokesperson told Public Health Watch it didn’t hold a public hearing because the concerns residents raised were for “activities outside of the USACE’s federal control and responsibility.”

Medcalf’s nonprofit, THEA, fought back.

In November 2024, THEA sued the Corps. The agency had violated federal permitting laws, the lawsuit said, by approving the project despite “appreciable opposition” from the public and despite the likelihood of “significant environmental impacts.”

Four months later, the Corps rescinded Holtmar’s letter of permission. Medcalf said the experience affirmed her belief that the maze of regulations governing the river is designed to keep the public out.

“The local community and THEA have sent … hundreds of letters opposing this permit, and it was ignored,” Medcalf said. “To then file suit and pretty quickly get the Corps to act, you know, it really said a lot. … The everyday person who is simply trying to have a voice of reason in the process that impacts their community is ignored.”

Holtmar did not respond when Public Health Watch asked if it will try again to install a barge terminal in the northern half of the river.

But more barges will almost certainly be coming to the crowded south end, where Jennie Ramsey and Carolyn Stone live.

In October, the Port of Houston opened 12 additional acres of the river to barges, less than two miles from their homes. According to a port spokesperson, the new leases will allow at least 20 more barges to enter the already beleaguered waterway.

Public Health Watch reporters David Leffler, Shelby Jouppi and Savanna Strott contributed to this article.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,