After spending the first 16 years of her federal government career focused on the impacts of climate change, Libby Jewett hoped to wrap up her time at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration working on solutions.

So in 2023, the marine ecologist gave up her post as the founding director of NOAA’s ocean acidification program, moved from Washington, D.C., to New England, and joined the agency team working on the permitting of offshore wind energy. Technically, it was a demotion, since she no longer was a manager, but Jewett was eager to help tackle the slew of projects proposed on the Atlantic Coast during President Joe Biden’s administration.

But that work, and Jewett’s career as a public servant, came to an abrupt halt soon after President Donald Trump took office. Amid the upheaval early last year as Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) slashed the federal workforce and Trump ordered a stop to U.S. offshore wind development, Jewett, 62, opted to retire.

DOGE was quietly disbanded in November after falling far short of its budget-cutting goals. Trump has escalated his war on offshore wind, citing unspecified secret national security risks, in an effort to maintain a halt on all projects in the face of a federal judge’s Dec. 8 ruling that such a ban was illegal. And the tumult of the first year of Trump’s second term lingers, destined to have a lasting impact on NOAA, in large part because of the exodus of experts like Jewett.

As Jewett looks ahead to continuing her work on climate change—including as an author on the next Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment—she also is reflecting on the work she and her colleagues did at NOAA. After a year of attacks on the federal workforce, Jewett hopes to help foster better public understanding of how government works and what agencies like NOAA do.

“I feel like the way that government functions well is that you have teams of people who are dedicated to the mission of the organization, and you listen to them, and you collectively come up with a better answer than if you tried to do it on your own,” Jewett said.

She had a chance to assemble such a team when evidence first emerged that greenhouse gases were transforming the chemistry of the oceans, putting at risk the nation’s $3 billion-a-year shellfish industry, the coral reefs that act as natural barriers against storms and support a quarter of all marine life and the millions of people who rely on healthy seas.

A Son’s Inspiring Field Trip

Jewett did not start out as a scientist, and instead had what she describes as a “meandering career” in public service. After growing up in the Washington, D.C., area—her father was general counsel for the Inter-American Development Bank—she majored in Latin American studies at Yale, then earned a master’s degree in public policy from the Harvard Kennedy School.

She worked on childcare issues for a nonprofit in Boston, then moved to an organization that assisted Central American refugees and later became a fundraiser for an environmental group focused on conservation initiatives in the Great Lakes. While working among environmentalists, she found herself longing for a better understanding of the science that informed their work.

At this point, Jewett and her husband, a doctor, had two children. Unexpectedly, she became even more drawn to science through her experiences as a parent. “I think it was on one of my son’s kindergarten field trips, and we were out doing something in streams,” Jewett said. “What I remember is thinking, ‘Oh my God, I love this.’”

In retrospect, she believes that exploring the water resonated with her because of her childhood summers spent in Maine. Her large family (she was one of six children) would pack provisions into a small boat and head to an uninhabited island to camp for two weeks in the outdoors, with activities and timing of their travel to the mainland dictated by the surrounding waters and weather. “When I started thinking about getting a Ph.D. in science, and about what kind of science that would be,” Jewett said, “there was never any doubt that it would be marine science.”

She enrolled in a graduate program at the University of Maryland, sometimes taking her children with her while she did her field work. They’d help her lift panels that she had lowered into the York River, near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, to see what type of organisms would attach themselves to the surfaces over time. Analysis of these so-called “fouling communities” of barnacles, algae and other organisms can tell much about the health of an ecosystem, including the impact of non-native species.

While commuting to the laboratory from her home each day, Jewett passed a large bronze work of art: an upturned hand releasing four gulls. It was the statue outside the Silver Spring, Maryland, headquarters of NOAA.

Jewett decided to apply to work at the agency, at first because it seemed like a convenient commute from home. Her academic colleagues warned her that joining a government agency would mean doing less science and attending more meetings. But in 2006, the year after earning her Ph.D., she became a contractor with NOAA’s National Ocean Service, working on the problems of harmful algal blooms. Jewett soon found that she had landed in precisely the work she had been seeking all along—applying science to benefit the public.

“The interface between policy and science was my dream, exactly,” Jewett said.

She helped develop a harmful algal bloom forecast for the coast of Texas, which informs coastal communities and industries about the location, size and movement of fast-growing cyanobacteria. These blooms, often caused by warm water, sunlight and excess nutrients from fertilizer runoff and other pollutants, release toxins that can harm people, pets and wildlife. Soon, Jewett became a full-time government employee and program manager for NOAA’s work on hypoxia, or low-oxygen episodes, a problem also tied to runoff pollution.

In addition to the work itself, Jewett enjoyed getting together with colleagues at NOAA to talk about new science. So she organized a “journal club.” It was kind of like a book club, but instead of books, members identified interesting scientific research papers to read and talk about over lunch. “It was something we did for fun on the side,” Jewett said, laughing.

For one lunch session, Jewett picked out new research that was being spearheaded by one of NOAA’s own scientists, Richard Feely, at the agency’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle. It was about a threat to shelled creatures like the ones that would attach themselves to the panels Jewett had studied near the Chesapeake Bay. In a series of studies beginning in 2004, Feely and his team had documented how carbon dioxide was changing not only the atmosphere, but the chemistry of the oceans, posing great risk to a wide variety of sea life.

An Industry “Scared to Death”

That journal club meeting, and a fortuitous meeting between Jewett and Feely, would begin a collaboration that, over time, launched NOAA’s work on ocean acidification. Feely got word that a group at NOAA headquarters was discussing his research and he reached out to Jewett. He and his team of scientists were convinced that ocean acidification already was a problem that required more than the research they were doing. It was a problem they believed that NOAA needed to act on.

In the Pacific Northwest beginning in 2005, oyster larvae in hatcheries had begun dying and production was plummeting due to what the farmers suspected was a bacterial disease. The industry, which supports 3,200 jobs in coastal Washington, had invested in sanitizing tanks to kill bacteria, but the problems persisted.

Feely suspected that Pacific oysters were the earliest known victims of ocean acidification. He met with farmers to explain how the seas were absorbing one quarter to one third of the carbon pollution generated each year by humanity’s burning of fossil fuels. The resulting chemical reaction causes the water to become more acidic and reduces the available calcium carbonate that is essential for the formation of shells and skeletons in marine life.

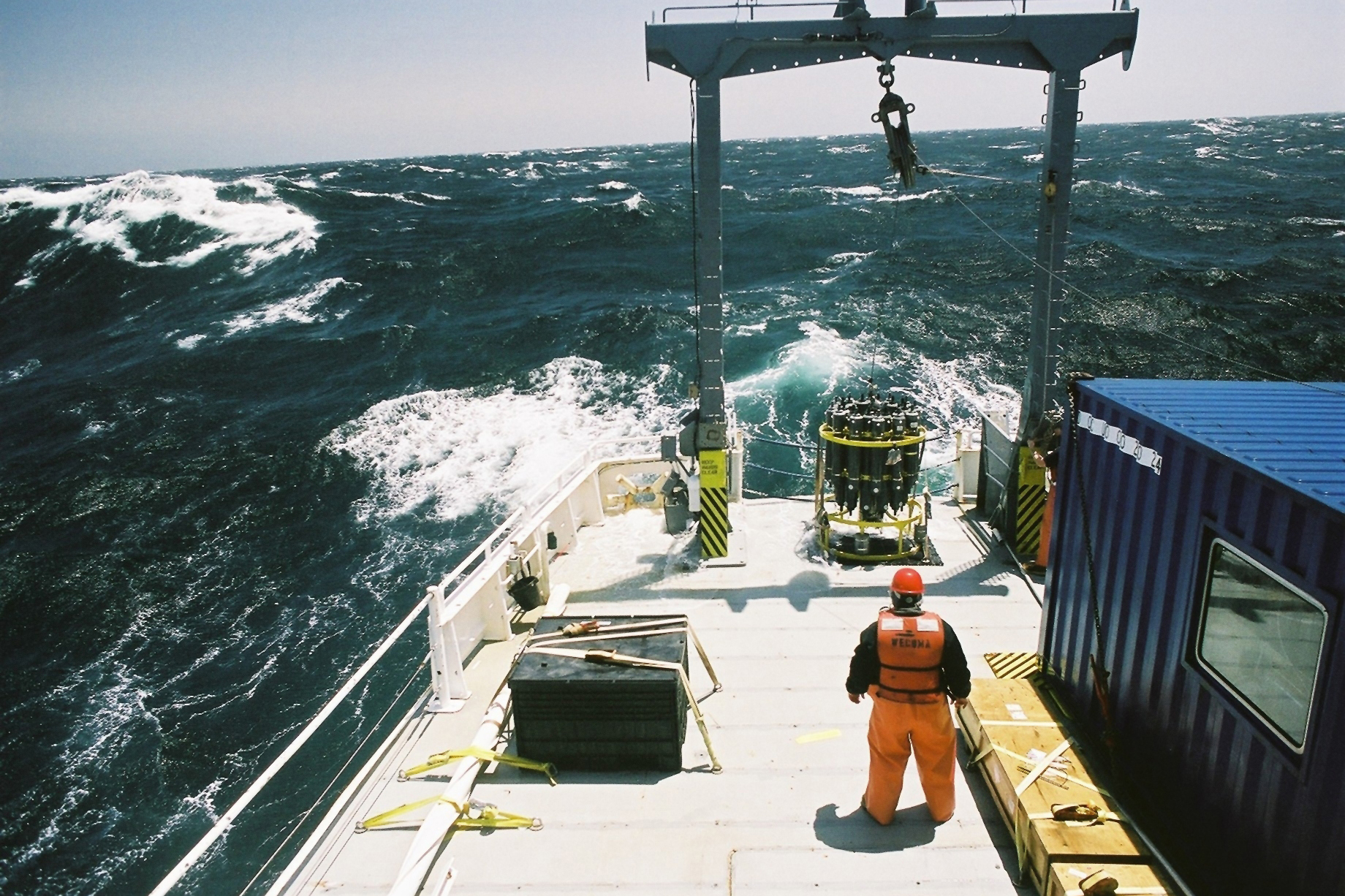

The problem was exacerbated on the West Coast because of upwelling patterns in the Pacific Ocean. Even though the oceans are vast enough to take in massive amounts of carbon, Feely led a research cruise survey of the western continental shelf in 2007 that confirmed that the most acidic waters from the deep were welling up regularly near the Pacific coast of North America. Previously, scientists had projected that carbon dioxide would cause problematic acidity in oceans “over the next several hundred years.” But Feely told the farmers his research indicated that levels were corrosive enough to interfere with oyster development now.

“They were flabbergasted,” Feely recalled recently. “And they were scared to death.”

But NOAA did more than deliver the bad news. The agency would provide help. Today, oyster growers—as well as fisheries and communities on all U.S. coasts, continental and island—rely on NOAA’s Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS), a network of buoys and sensors, to provide real-time data on ocean acidity. The Pacific Northwest oyster industry has been able to dramatically improve survival rates by taking steps such as chemical buffering or avoiding filling tanks with seawater at times when acidity levels are too high.

Feely credits Jewett with leading what he describes as “the visionary work” to make it happen. She helped assemble a NOAA team to develop the strategic research plan that became the blueprint for the agency’s ocean acidification work.

“She was the coordinating person who brought everybody together, kept expanding and kept making sure that everybody was well organized and well structured,” Feely said. “Just an amazing leader. She had a great way of making people feel comfortable working together. She was so encouraging, always very positive and always seeing where the future could lie.”

Darcy Dugan, who led the development and launch of Alaska’s ocean acidification network and is now its director, agrees. “When I think of Libby, I just think of this ray of light, and her warmth and her curiosity and her commitment to collaboration,” Dugan said. “She was super-committed to science and was very pioneering. She also cared about relationships and had a way of always making you feel valued.”

Part of NOAA’s job was communicating to Congress the national economic implications of the threats to premium species in U.S. fisheries, like lobsters, crabs and sea scallops. Even though shellfish accounted for just 17 percent of U.S. commercial fishery landings in 2022, the most recent year for which data is available, they provided 51 percent of the $5.9 billion value of the industry’s catch.

Feely testified repeatedly before Congress as Jewett and her team worked behind the scenes. With urging from the shellfish industry and state officials, Congress passed the first law in the world to address the problem, the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring Act (FOARAM), in 2009. Jewett would become NOAA’s first ocean acidification program director, and the first female director in the agency’s Oceanic and Atmospheric Research division. Under her leadership, NOAA chaired an interagency working group of 14 federal agencies engaged on the issue. And the work extended beyond the U.S. borders. The United States was instrumental in the launching of the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON) in 2012, now involving 114 countries.

Ocean climate scientist Sarah Cooley first worked with Jewett when she was a NOAA outside research partner, based at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. Cooley remembers being impressed at how Jewett made sure NOAA’s ocean acidification program was not just academic but rooted in the needs of communities reliant on the sea.

“I would say one of the things that Libby really did that was very unique was she saw how to bring together the natural systems piece of the research and the social systems piece of the research,” Cooley said. “And I think that’s very unusual in a program in NOAA’s OAR. A lot of those research programs are very natural-systems focused. But Libby really led bringing in that community-needs focus.”

Jewett credits her team with bringing that emphasis to the human dimensions of the ocean acidification problem. They realized it was lacking in early versions of the plan, she said. “At some point, pretty early on, my staff came to me and said, ‘We need to rethink this,’” she recalled. Instead of starting out trying to figure out all the marine organisms that were vulnerable, they urged that NOAA’s program first consider the people. “We need to consider how humans are vulnerable to ocean acidification either through the food they eat, cultural practices or places they visit,” Jewett recalled. From there, NOAA could work backward to assess the marine species, considering them as part of a socio-ecological system.

“This was a turning point for the program,” Jewett said. “Being challenged by my staff was good for the program and something any good leader should receive humbly and consider seriously.”

NOAA’s ocean acidification plan therefore emphasized the need for local and regional studies, recognizing, for instance, that some Indigenous communities rely on vulnerable species for subsistence, and that a coastal community relying exclusively on tourism related to a coral reef ecosystem might be more culturally and economically vulnerable than a community with a highly diversified economic base.

NOAA’s work has helped the industry and coastal communities better cope with ocean acidification, but the problem is far from solved. A NOAA-funded University of Washington study published last year showed that owners and operators of Pacific Northwest shellfish aquaculture facilities now view ocean acidification as a lower-priority concern than marine heat waves, disease and harmful algal blooms. The researchers said more effort was needed to communicate how all of these stressors are interconnected, and how solutions such as diversification of species could help with all these challenges.

One of the final things that Jewett worked on as program manager was a review of all the federal government had accomplished on ocean acidification and all that was left to do. The U.S. Ocean Acidification Action Plan, released by the Biden administration in 2023, called for further advances in research and monitoring, including through the use of artificial intelligence, and researching promising strategies for mitigating acidification—for example, through seagrasses and other plant life that can take up excess carbon dioxide from seawater. The plan also called for accelerating research into nascent ideas for marine carbon removal technology—both their promise and their potential risks.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe idea of focusing more on climate solutions appealed to Jewett, especially the most important solution—reducing the carbon pollution from fossil fuels. NOAA had new and important work in this area—the environmental analysis on offshore wind. After working on a temporary detail with NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, she decided to join that team on a permanent basis.

Finding a successor for Jewett as director of the ocean acidification program was a lengthy process, not that unusual for a government leadership position. After a nationwide search, the post went to Cooley, who by then had spent a decade at the Ocean Conservancy, including as director of its ocean acidification program and more recently as its senior director for climate science. Cooley took the helm of the program in August 2024.

But Jewett’s work in NOAA’s offshore wind program, Cooley’s leadership of the agency’s ocean acidification program and indeed, the future of all the federal government’s climate work, were thrown into chaos soon after Trump took office in January 2025.

“A Psychological Push to Get Us Out”

For Jewett, the new administration brought an abrupt stop to 18 months of running full speed to keep up with the burgeoning offshore wind business. “It was really crazy, fast-paced work, because there was a big push on the part of the Biden administration,” she said. There were no commercial wind energy projects in U.S. waters when Biden took office; his administration had approved 11 by the end of 2024 and proposals for more were under consideration.

NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center was tasked with providing the scientific data and environmental reviews to ensure that marine ecosystems, fisheries and coastal communities were protected amid the drive to deploy offshore wind. Working with that team, Jewett was drawing on her experience launching the agency’s ocean acidification research portfolio, “trying to be thoughtful about how we were investing the money we had,” she said.

But on his first day in office, Trump signed two executive orders that were “the first blow and the second blow” that knocked Jewett out of her career at NOAA. He withdrew all federal offshore areas from leasing for wind energy, and began a review of all the offshore wind decisions that had already been made, signaling his plan to terminate them.

At the same time, Trump ordered a termination of all remote work arrangements. Jewett and her husband had settled in Vermont and she had been working remotely from her home, coming into the NOAA office in Rhode Island as was needed—essentially, every two weeks. To stay with the federal government would mean both personal upheaval and professional uncertainty.

NOAA also quickly became a particular target of Musk and the DOGE team, and soon hundreds of agency workers were being laid off.

“There was kind of this psychological push to get us out,” Jewett said. “They wanted as many people as possible to retire and, in fact, they kind of dangled this idea that if enough people left then earlier career scientists might not have to leave. And I felt like I’m OK with that trade-off, because I’ve gotten to know these incredible scientists who are early in their career, and they’re doing great science. They should stay and be the future of the agency.”

Jewett retired on April 30, but the future of the agency looked even more uncertain when the Trump administration’s fiscal year 2026 budget proposal came out the following month. NOAA’s fisheries and ecosystem science programs would get a 25 percent cut, with the offshore wind work phased out altogether, even though the agency’s job was to help minimize marine life impacts—at times, Trump’s stated issue with the industry.

Jewett’s old program, ocean acidification, also was going through turmoil. Cooley, in her position as program leader for less than a year, was one of thousands of probationary employees across the federal government who were laid off in February. “I just couldn’t believe this was happening,” Jewett said.

Cooley, who will take over as executive director of the nonprofit Earth Science Information Partners in January, said she realized she was vulnerable at the start of Trump’s second term. Even though her deputy told her she was being “morbid,” she said she made sure she had another colleague with her at every meeting so there would be continuity.

“I started building redundancy into our program so that the work could continue,” Cooley said.

On paper, NOAA’s ocean acidification program is, indeed, continuing. But in reality, it is hobbled by cutbacks, according to those familiar with its work. Fewer research grants are being issued than in previous years. And there are local impacts. For instance, instruments at NOAA’s remote Kodiak, Alaska, site that were designed to provide continuous monitoring of ocean acidity conditions couldn’t be used last year because the technician position was eliminated, said Dugan of Alaska’s Ocean Observing System.

Although the Trump administration’s Fiscal Year 2026 budget proposal would continue the Congressionally mandated ocean acidification program, it would zero out the funding that flows to the regional ocean observing systems like Alaska’s that do the monitoring that are a linchpin of the program. There’s bipartisan opposition to deep cuts at NOAA, but no final decisions have been made, and the agency is operating with stopgap funding through January.

“We’ve had a lot of conversations about, ‘How do we navigate this?’,” Dugan said. “And some of the scenarios were pretty bleak. We’ve felt a sense of relief for this [fiscal] year’s funding, but it’s hard to be in this space of uncertainty.”

Another linchpin of the ocean acidification program, pioneering scientist Richard Feely, also is gone. He retired in September after 51 years at the agency. Eligible to retire much earlier—Jewett said Feely was talking about retirement from the day she met him—Feely, 78, stayed long enough to see his science make a positive difference in people’s lives, he told the representatives of the Pacific Northwest fisheries industry and coastal community who attended his retirement party.

“I said the reason I stayed so long is because you guys responded to the research that we provided you,” Feely said. “I saw how our community changed because of the research, and I couldn’t walk away from it.”

He is especially proud of the U.S. leadership that led to the growth of ocean acidification research and monitoring around the world. “Most people say that the fisheries management in the United States is the best there is,” Feely said. “And I think that is because such good coordination occurs, because of the impact of NOAA science and the fisheries research efforts that have occurred in this country.”

Although Jewett is at peace with her own departure from NOAA, she is worried about the long-term impact of the past year’s mass exodus from NOAA. “It’s like the institutional memory of the organization,” she said. “All these leaders of things who’ve been around for a long time and know how it operates, we’re kind of moving on.”

In August, Jewett got word that she has been selected to serve as one of about 50 U.S. authors who will be working on the next assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. She’ll be working on the so-called “Working Group II” report—back to assessing the impacts of climate change, rather than helping deploy the solutions, as she hoped to be doing now. “I am proud to carry the torch for all the NOAA scientists who cannot serve on this round of the assessment,” Jewett said in a post announcing the news on LinkedIn.

NOAA has lost close to 2,000 of its 11,800 employees through layoffs and retirements since Trump took office, according to members of Congress. If these numbers are true, agency staffing is at its lowest level since the agency’s creation in 1970.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,