This article was originally published by Capital B.

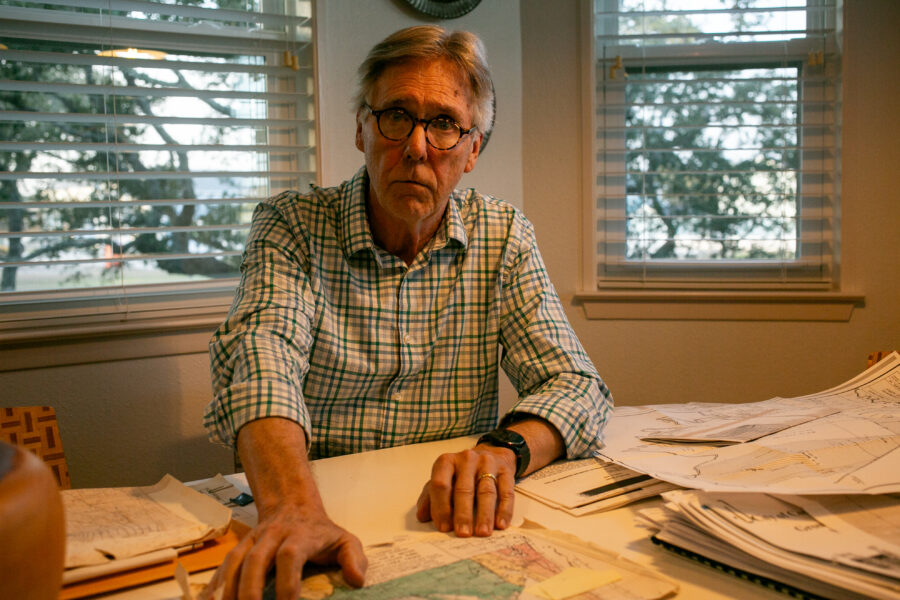

On Saturday morning, John Beard woke up to news that he’d been dreading, but preparing for: A global oil crisis could hit closer to home in Texas.

The southeastern part of the state is home to more than a dozen oil refineries, and he’d spent decades working at one of them. But after attending more funerals than he could count for loved ones who died from cancer, he began to feel differently about the job.

Beard has spent the past year doing “extensive work” in Europe, warning allies about the dangers of expanding fossil fuels and urging them to prepare to “stand up and push back” against U.S. and industry plans under the Trump administration. He has also been coordinating with local advocates to scrutinize new industrial proposals in Port Arthur, his hometown in southeast Texas, which is home to several oil refineries.

Nearly half of the people living in his neighborhood report living with “poor” health, according to federal data. And the risk for developing cancer caused by air pollution is essentially the highest in the country at 1 in every 53 residents.

Beard fears it may get worse.

For him, the recent U.S. airstrike on Venezuela, which killed at least 40 citizens and has been framed as a push to restore democracy, has landed as something far more familiar: a fight over oil.

Until 2010, Venezuela was one of the world’s largest oil producers, but over the past 15 years the country’s oil production fell sharply as U.S. sanctions crippled its exports and Venezuela’s government limited output to retain control over the resource. Today, Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, a critical resource only becoming more valuable as global supplies tighten and energy demands surge.

President Donald Trump has said the U.S. will be taking over the nation’s oil reserves—keeping some for the U.S. while selling millions of barrels to other countries.

For Beard’s home and dozens of other Black communities along the Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Texas, “that’s going to be more pollution and cancer,” the community advocate said. “This is an extenuation of the problem the industry has already created and a fight to make sure there is no way out.”

Texas—particularly Beard’s hometown and neighboring Beaumont—and Louisiana make up the densest regional cluster of large refineries on the planet. And those facilities were originally designed for processing dense, sulfur-rich crude from countries like Venezuela. Years of disruption forced them to rely on Canadian tar sands and Middle Eastern blends, which increased costs for American oil companies. This last push for Venezuelan oil, experts said, is an attempt to restore profitability and strengthen the U.S. supply chain.

Prior to Venezuela’s push to keep control over its oil, the country’s oil made up about 15 percent of the oil refined in America. Since then, it is about 3 percent. But with U.S. control over the country’s oil industry, the amount of Venezuela oil in the U.S. is expected to increase exponentially.

“Trump now joins the history of U.S. presidents who have overthrown regimes of oil-rich countries. Bush with Iraq. Obama with Libya,” said Ed Hirs, an energy fellow at the University of Houston. “In those cases, the United States has received zero benefit from the oil. I’m afraid that history will repeat itself in Venezuela.”

Hirs argues that the physical control of reserves won’t translate to cheaper prices at American pumps, rather just increase the bottom lines of oil companies. Trump said he shared his plans to attack Venezuela with the leaders of U.S. oil companies before the bombings happened over the weekend.

Venezuelan crude oil is much worse for the environment than the typical lighter grades used in the U.S. today. “Burning any type of oil contributes to climate change, but Venezuela’s oil is among the dirtiest oils in the world to produce when it comes to global warming,” said Paasha Mahdavi, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

But for refinery operators, the economics are compelling because the heavy crude is $5 to $15 cheaper per barrel.

Every year, 91,000 people die prematurely in the U.S. due to pollution events from the country’s oil and gas industry, according to a landmark yearslong study of health outcomes in communities near oil and gas facilities.

Black and Asian people are most likely to experience these negative health outcomes from oil and gas, which include 10,350 preterm births, 216,000 childhood cases of asthma and 1,610 cancer cases every year. These communities in Texas and Louisiana are hit the hardest by far, the study concluded.

U.S. Rep. Jasmine Crockett from Texas said the bombing of Venezuela and the kidnapping of the nation’s president, Nicolás Maduro, is “not what the American people asked for.”

“People can’t afford groceries and millions are losing health care, but this is where his focus is,” she said.

Job Growth Unlikely

The Trump administration has suggested that American oil companies and workers will be sent to Venezuela to rebuild the oil infrastructure destroyed by years of economic collapse and sanctions. But Beard, who has spent decades watching industrial development promises fail to materialize in his own community, is deeply skeptical.

“What I thought was so funny was to hear the president say that the companies are going to go in there and they’re going to help them rebuild the infrastructure and do this and do that,” he said. “But they’re not doing it here; we have accidents weekly. So what does that tell us about what they think about us?”

Any job growth from increased Venezuelan oil refining is unlikely to reach Gulf Coast communities, despite the billions in industrial investment that flows through the region, experts said.

In the best case scenario, “it will take about a decade and about a hundred billion dollars of investment,” said Francisco Monaldi, who is the director of the Latin America Energy Program at Rice University in Houston.

Just three companies—Valero Energy, Chevron and PBF Energy—process 80 percent of all Venezuelan crude imported to the U.S., and are best positioned to reap the benefits of the U.S. occupation of Venezuela.

Despite southeast Texas and Louisiana seeing over $100 billion in industrial development, the majority-Black communities around these industries consistently rank among the highest in unemployment, a pattern Beard describes as “environmental racism.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowIn Lake Charles, Louisiana, there are three major oil refineries, including the Citgo refinery, which is the seventh-largest in the world and already a major refiner of Venezuelan oil.

For years, Debra Ramirez, who has spent her whole life in the area, has driven around with a laminated list of where the oil being refined in her backyard comes from.

She said she arrived at the realization that the Venezuelan oil crisis was coming long before Trump ever spoke about it.

Her community of Mossville, once a self-sufficient enclave with hunting grounds, gardens and tight-knit neighborhoods where families shared their harvests with one another, was systematically dismantled by the petrochemical plants that surround Lake Charles. Many residents died from cancer-related illnesses and documented toxic blood contamination.

“They destroyed our home, and they can never ever give back,” she said.

For Ramirez, Beard and others like them, increased Venezuelan crude refining doesn’t represent progress or “America first.”

“This is just the same old extraction and disposability that has already devastated our world,” Beard said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,