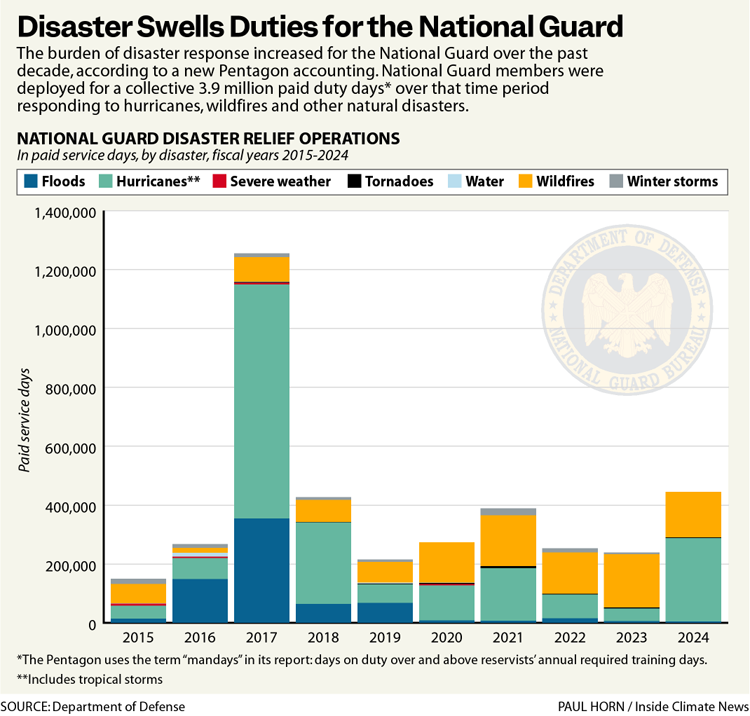

The National Guard logged more than 400,000 member service days per year over the past decade responding to hurricanes, wildfires and other natural disasters, the Pentagon has revealed in a report to Congress.

The numbers mean that on any given day, 1,100 National Guard troops on average have been deployed on disaster response in the United States.

Congressional investigators believe this is the first public accounting by the Pentagon of the cumulative burden of natural disaster response on the National Guard.

The data reflect greater strain on the National Guard and show the potential stakes of the escalating conflict between states and President Donald Trump over use of the troops. Trump’s drive to deploy the National Guard in cities as an auxiliary law enforcement force—an effort curbed by a federal judge over the weekend—is playing out at a time when governors increasingly rely on the Guard for disaster response.

In the legal battle over Trump’s efforts to deploy the National Guard in Portland, Oregon, that state’s attorney general, Dan Rayfield, argued in part that Democratic Gov. Tina Kotek needed to maintain control of the Guard in case they were needed to respond to wildfire—including a complex of fires now burning along the Rogue River in southwest Oregon.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, rejects the science showing that climate change is worsening natural disasters and has ceased Pentagon efforts to plan for such impacts or reduce its own carbon footprint.

The Department of Defense recently provided the natural disaster figures to four Democratic senators as part of a response to their query in March to Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth regarding planned cuts to the military’s climate programs. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who led the query on behalf of herself and three other members of the Senate Committee on Armed Services, shared the response with Inside Climate News.

“The effects of climate change are destroying the military’s infrastructure—Secretary Hegseth should take that threat seriously,” Warren told ICN in an email. “This data shows just how costly this threat already is for the National Guard to respond to natural disasters. Failing to act will only make these costs skyrocket.”

Neither the Department of Defense nor the White House immediately responded to a request for comment.

Last week, Hegseth doubled down on his vow to erase climate change from the military’s agenda. “No more climate change worship,” Hegseth exhorted, before an audience of senior officials he summoned to Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia on Oct. 1. “No more division, distraction, or gender delusions. No more debris,” he said. Departing from the prepared text released by the Pentagon, he added, “As I’ve said before, and will say again, we are done with that shit.”

But the data released by the Pentagon suggest that the impacts of climate change are shaping the military’s duties, even if the department ceases acknowledging the science or planning for a warming future. In 2024, National Guard paid duty days on disaster response—445,306—had nearly tripled compared to nine years earlier, with significant fluctuations in between. (The Pentagon provided the figures in terms of “mandays,” or paid duty days over and above Guard members’ required annual training days.)

Demand for National Guard deployment on disaster assistance over those years peaked at 1.25 million duty days in 2017, when Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria unleashed havoc in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico.

The greatest deployment of National Guard members in response to wildfire over the past decade came in 2023, when wind-driven wildfires tore across Maui, leaving more than 100 people dead. Called into action by Gov. Josh Green, the Hawaii National Guard performed aerial water drops in CH-47 Chinook helicopters. On the ground, they helped escort fleeing residents, aided in search and recovery, distributed potable water and performed other tasks.

Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois joined Warren in seeking numbers on National Guard natural disaster deployment from the Pentagon.

It was not immediately possible to compare National Guard disaster deployment over the last decade to prior decades, since the Pentagon has not published a similar accounting for years prior to 2015.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowBut last year, a study by the Rand Corporation, a research firm, on stressors for the National Guard said that service leaders believed that natural disaster response missions were growing in scale and intensity.

“Seasons for these events are lasting longer, the extent of areas that are seeing these events is bigger, and the storms that occur are seemingly more intense and therefore more destructive,” noted the Rand study, produced for the Pentagon. “Because of the population density changes that have occurred, the devastation that can result and the population that can be affected are bigger as well.”

A history of the National Guard published by the Pentagon in 2001 describes the 1990s as a turning point for the service, marked by increasing domestic missions in part to “a nearly continuous string” of natural disasters.

One of those disasters was Hurricane Andrew, which ripped across southern Florida on Aug. 23, 1992, causing more property damage than any storm in U.S. history to that point. The crisis led to conflict between President George H.W. Bush’s administration and Florida’s Democratic governor, Lawton Chiles, over control of the National Guard and who should bear the blame for a lackluster initial response.

The National Guard, with 430,000 civilian soldiers, is a unique military branch that serves under both state and federal command. In Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, the president called on the National Guard to serve alongside the active-duty military. But state governors typically are commanders-in-chief for Guard units, calling on them in domestic crises, including natural disasters. The president only has limited legal authority to deploy the National Guard domestically, and such powers nearly always have been used in coordination with state governors.

But Trump has broken that norm and tested the boundaries of the law. In June, he deployed the National Guard for law and immigration enforcement in Los Angeles in defiance of Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom. (Trump also deployed the Guard in Washington, D.C., where members already are under the president’s command.) Over the weekend, Trump’s plans to deploy the Guard in Portland, Oregon, were put on hold by U.S. District Judge Karin J. Immergut, a Trump appointee. She issued a second, broader stay on Sunday to block Trump from an attempt to deploy California National Guard members to Oregon. Nevertheless, the White House moved forward with an effort to deploy the Guard to Chicago in defiance of Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker, a Democrat. In that case, Trump is calling on Guard members from a politically friendly state, Texas, and a federal judge has rejected a bid by both the city of Chicago and the state of Illinois to block the move.

The conflicts could escalate should a natural disaster occur in a state where Trump has called the Guard into service on law enforcement, one expert noted.

“At the end of the day, it’s a political problem,” said Mark Nevitt, a professor at Emory University School of Law and a Navy veteran who specializes in the national security implications of climate change. “If, God forbid, there’s a massive wildfire in Oregon and there’s 2,000 National Guard men and women who are federalized, the governor would have to go hat-in-hand to President Trump” to get permission to re-deploy the service members for disaster response, he said.

“The state and the federal government, most times it works—they are aligned,” Nevitt said. “But you can imagine a world where the president essentially refuses to give up the National Guard because he feels as though the crime-fighting mission has primacy over whatever other mission the governor wants.”

That scenario may already be unfolding in Oregon. On Sept. 27, the same day that Trump announced his intent to send the National Guard into Portland, Kotek was mobilizing state resources to fight the Moon Complex Fire on the Rogue River, which had tripled in size due to dry winds. That fire is now 20,000 acres and only 10 percent contained. Pointing to that fire, Oregon Attorney General Rayfield told the court the Guard should remain ready to respond if needed, noting the role reservists played in responding to major Oregon fires in 2017 and 2020.

“Wildfire response is one of the most significant functions the Oregon National Guard performs in the State,” Rayfield argued in a court filing Sunday.

Although Oregon won a temporary stay, the Trump administration is appealing that order. And given the increasing role of the National Guard in natural disaster response, according to the Pentagon’s figures, the legal battle will have implications far beyond Portland. It will determine whether governors like Kotek will be forced to negotiate with Trump for control of the National Guard amid a crisis that his administration is seeking to downplay.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,