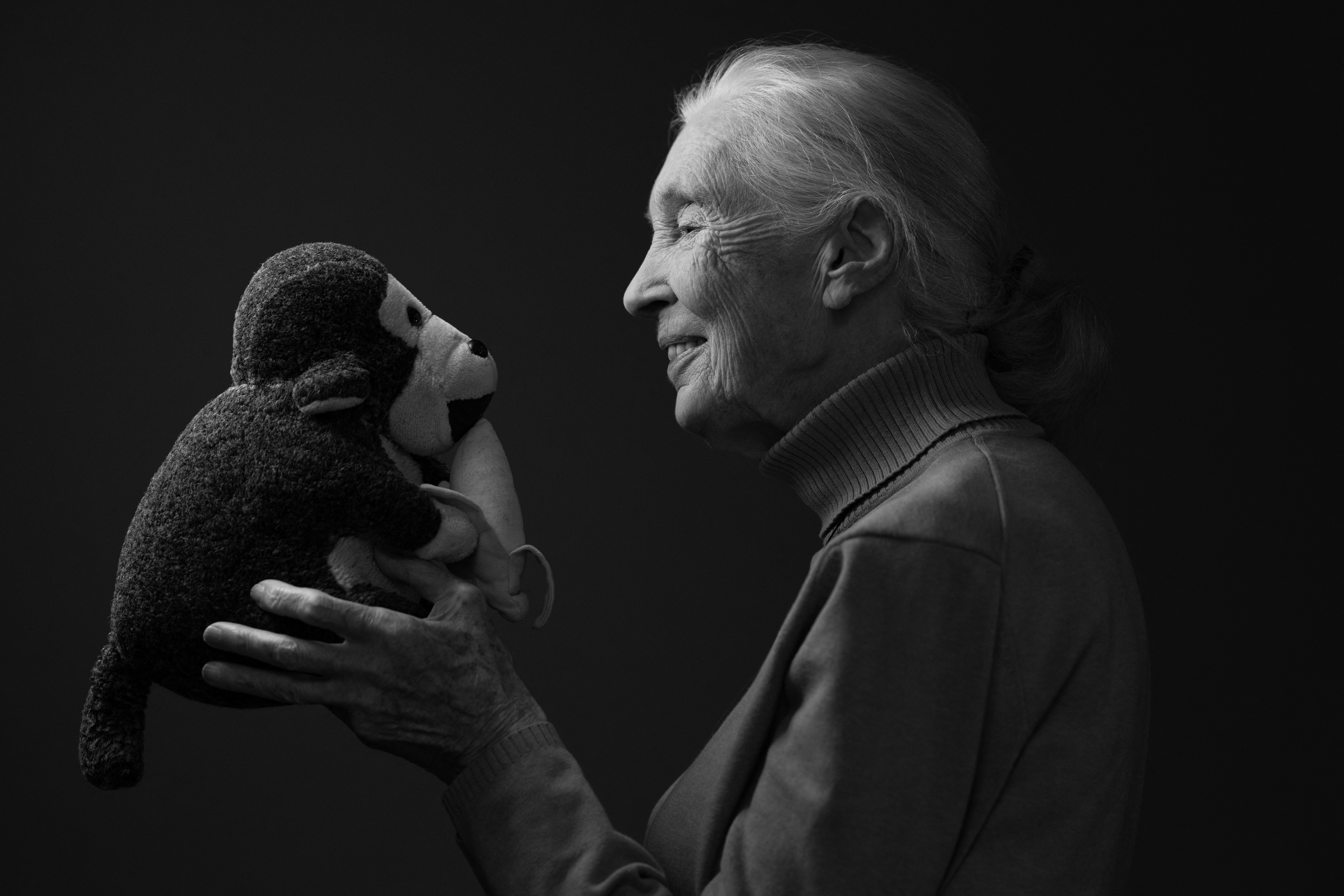

Last week, the world lost a conservation giant.

On Oct. 1, renowned primatologist and environmental advocate Jane Goodall died at the age of 91. The British scientist is most famous for her work with chimpanzees, which she embedded with for years in the forests of Tanzania to uncover more about their lives in the wild.

Goodall’s insatiable curiosity for the natural world grew into a fierce, decades-long global campaign to protect the environment from the intertwined threats of biodiversity loss and climate change. Though many mourn her passing and the loss of a major force in the fight for nature, they also stress the far-reaching and long-term impact of her work on the next generation of scientists and conservationists.

And Goodall herself left behind a message for the world in a unique interview with streaming platform Netflix, which was only to be released upon her death.

“There’s so much we have still to discover,” she said in the interview. “I know when I’m gone, there’ll be more and more discovered if we can save the planet in time.”

Redefining Humanity: In 1960, when Goodall was just 26, she accepted a research position that would not only change her life, but also the understanding of what it means to be a human or an ape.

Under the guidance of paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, Goodall set out for a long-term project closely studying the lives of chimpanzee troops in Tanzania. There, she observed the wild apes more closely than any scientist had before, watching chimpanzees hug and kiss each other, fight over resources and even use tools to gather food, which experts had previously thought was a capability only humans had.

“Now we must redefine ‘tool,’ redefine ‘man,’ or accept chimpanzees as human,” Leakey said of Goodall’s groundbreaking discovery. While unraveling the lives of chimpanzees, Goodall also saw firsthand how human activities were contributing to an uptick in the animals’ deaths, from rampant hunting to fuel the bush meat trade to habitat loss from deforestation. With this in mind, she launched the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977 to help support further research in the region and protect chimpanzee habitat.

The institute and Goodall’s conservation work only grew from there. In recent decades, she worked tirelessly to help reduce the plight of chimpanzees used in laboratory testing in the U.S., protect other endangered species and slow climate change. In 2002, Goodall was deemed a United Nations Messenger of Peace for her work. A prolific primatologist, global icon and one of the most outspoken advocates for nature, she wrote more than 30 books and appeared regularly in National Geographic magazine and on television programs.

She said on several occasions this communications push was a big part of her main mission: to inspire hope and spark action in others.

“Hope is often misunderstood,” Goodall wrote in her 2021 work, “The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times,” which was co-written by author Douglas Abrams. “People tend to think that it is simply passive wishful thinking. … This is indeed the opposite of real hope, which requires action and engagement.”

Lasting Legacy: Goodall was hands-on in her support of young conservationists. She launched a program through her institute called Roots & Shoots, which teaches young people in more than 60 countries about nature conservation and how to make a difference in their communities.

From the start of her career, Goodall was breaking glass ceilings for women, especially those in science who were not given many opportunities to research in the field during the 20th century. Many researchers have attributed her work as a motivator in their own careers.

“It was after reading her books that I put on my boots and binoculars and went out in the jungle,” Catherine Crockford, an expert on chimpanzees at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, told The New York Times.

I can personally attest to the impact Goodall has had on my own career as a research student turned environmental journalist, whether in moments of fear or wonder in nature. But it’s not just those studying or writing about nature who Goodall reached. Recently, she appeared on pop culture shows like the “Late Show With Stephen Colbert” and podcast “Call Her Daddy” to chat about conservation (and how politicians are much like chimpanzees).

Last Friday, Netflix released what is perhaps Goodall’s final interview on the company’s new show “Famous Last Words,” which are only released posthumously. Though often praised for her calm demeanor, Goodall voiced her frustration and fear about recent actions to speed up the destruction of nature and climate change that governments, political leaders and business owners around the world have taken. She mentioned President Donald Trump, billionaire Elon Musk, President Vladimir Putin of Russia, President Xi Jinping of China and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel specifically.

But in her final message to the world, she stresses the power of individual action to protect instead of destroy.

“We have to do everything in our power to make the world a better place for the children alive today and for those that will follow,” she said. “You have it in your power to make a difference. Don’t give up. There is a future for you. Do your best while you’re still on this beautiful planet Earth that I look down upon from where I am now.”

More Top Climate News

At least 170 hospitals in the U.S. face significant risk of flooding, which could threaten patient care, according to an investigation from KFF Health News. Incorporating data from flood simulation provider Fathom, the report found that much of this issue is not captured by publicly available flood maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Experts say cuts to federal agencies that help respond to disasters, such as FEMA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, could make the situation worse.

From extreme heat to wildfire smoke and ash, the impacts of climate change are hurting our skin, Olivia Ferrari reports for National Geographic. A growing number of studies find that global warming is aggravating eczema and skin dryness, while air pollution from wildfires is invading pores, which can cause irritation. Experts recommend staying hydrated and using moisturizers and sunscreens, which can provide a shield against pollution.

Science teachers who rely on federal data and tools to teach their students about climate change are struggling to fill gaps as the Trump administration removes or restricts access to online databases like climate.gov, Gaea Cabico reports for Science. An academic consortium created guidelines known as the Next Generation Science Standards that recommends teachers introduce human-caused climate change to students in science classes starting in fifth grade. Science teachers depend on vetted visualizations or language from federal databases and collections to help with this, but are now forced to find many of these resources elsewhere.

“Science is always expanding,” Jeffrey Grant, who works at Downers Grove North High School in Illinois, told Science. “So, it is important that I always provide them with the latest research.”

Postcard from … North Carolina

For this installment of “Postcards From,” Today’s Climate reader Wendy Carlton sent in a photo she took during some backyard birding in Cashiers, North Carolina. These red-mohawked critters are known as pileated woodpeckers.

Today’s Climate readers, please keep sending in your photos for our “Postcards From” feature to [email protected]. We love seeing how you all interact with nature, whether birding in your backyard or hiking on vacation.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,