This story by Public Health Watch is part of a collaboration with Univision 45 in Houston.

HIGHLANDS, Texas—Eight months ago, Texas health officials delivered alarming news to residents of a string of industrialized communities east of Houston: A new study had found that they may be at elevated risk of developing several types of cancer, especially leukemia.

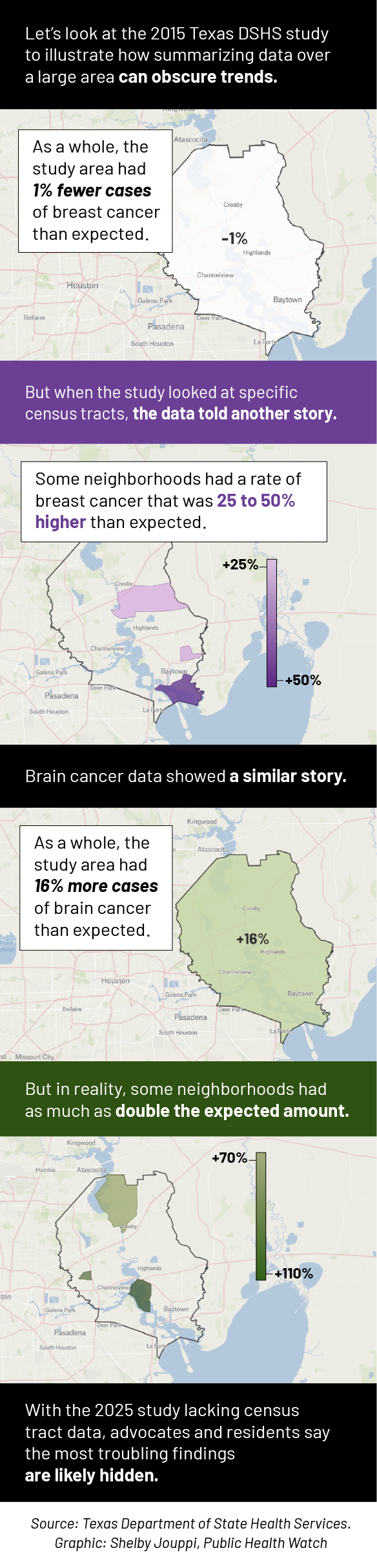

But few conclusions about the severity of the threat in specific locations can be drawn because state epidemiologists have refused to release the cancer data at the census-tract level—a move advocates and experts are calling into question. This granular data can pinpoint areas with high cancer burdens and help connect those discrepancies to risk factors like environmental exposures. It can also be used to identify cancer clusters.

Two independent epidemiologists told Public Health Watch the state’s decision not to release this data was illogical and indefensible. A Houston-area congresswoman and three Harris County commissioners sent letters to the state’s health commissioner, asking her to remedy the error. A local activist accused health officials of suppressing information that could reflect poorly on the state’s $68 billion oil-refining and petrochemical industries, centered in Houston.

Ketki Patel is the Texas Department of State Health Services, or DSHS, epidemiologist who led the study. In an interview, Patel defended the agency’s decision to publish cancer data for a 250-square-mile area—about a quarter of the size of Rhode Island—without providing details at the census-tract level. She said the agency can’t release such data because, for some cancer types, it didn’t find enough cases to guarantee statistical reliability.

“How am I going to drill down just to individual census tracts [if there aren’t enough instances of cancer]? It’s just mathematically not possible,” Patel said. “And we’re not going to be able to release those data because of patient privacy laws that we have to abide by.”

But the state released census-tract level data in a similar cancer study of the area in 2015, a decision Patel attributed to protocols in effect at the time. Two epidemiologists with whom Public Health Watch consulted said there was no reason to withhold such data this time.

“It doesn’t make any sense at all,” said Kyle Steenland, a professor in the departments of environmental health and epidemiology at Emory University. “This [new] study found a three-fold excess of leukemia [across all] 65 census tracts. It’s shocking—more than 300 cases of leukemia when the state was expecting 100. This is either a systematic error, or the entire state of Texas should be mobilized to find out why this is true.”

Asked about those leukemia cases, a DSHS spokesperson responded, “When I’ve looked at these [studies], there have been some that have been much, much higher over the years than that.”

Patel’s team spent most of 2024 studying cancer rates on the industrialized east side of Harris County. Among the places it surveyed were Highlands and Channelview, two unincorporated communities located along the San Jacinto River that were profiled in the first season of Public Health Watch’s investigative podcast, Fumed. Both areas are besieged by petrochemical companies fighting for waterfront property near the Houston Ship Channel. Both are uncomfortably close to an underwater Superfund site filled with dioxin-laced waste, which has been linked to cancer, reproductive problems and developmental disorders in children.

The DSHS investigation was requested by the Texas Health and Environment Alliance, or THEA, a nonprofit advocacy group led by former Highlands resident Jackie Medcalf. Medcalf, 39, suffered a litany of health problems during the decade she lived in the community of 7,000—problems she believes were tied to her home’s proximity to the Superfund site and the well water her family drank from and showered in.

Medcalf’s hair fell out. Bleeding sores broke out across her body. She started having seizures. She lost control of her extremities and became so weak that her mother had to accompany her to college classes and carry her to bed each night. Eventually, doctors discovered 19 heavy metals in Medcalf’s body, including chromium, mercury and arsenic—all found in the Superfund site. In 2014, she was also diagnosed with endometriosis, a chronic condition of the uterine lining that causes cysts, infertility and increases the chances of cervical cancer. Some studies have connected endometriosis to toxic exposures. Medcalf was told she’d never have children.

Environmental Hazards Concentrated in Southern Part of Study Area

The area DSHS scientists studied in East Harris County is home to several environmental hazards—including toxic Superfund sites, barges storing petrochemicals and facilities emitting volatile organic compounds, a class of chemicals that includes many carcinogens. But these hazards are largely concentrated in certain communities, worrying residents about concealed cancer clusters.

Hold command and scroll or use the -/+ in the bottom lefthand corner to zoom into the outlined study area. Click the arrows in the top right corner to view full-screen.

In 2015, DSHS scientists published the results of a cancer study conducted at Medcalf’s behest. The investigation found elevated rates of the disease across a sprawling area in the San Jacinto River’s floodplain. Elevated incidence of leukemia, myeloma, liver cancer, kidney cancer, and childhood brain cancer were among the most troubling findings. The study highlighted specific census tracts with the highest rates of those cancers.

In a letter to DSHS on January 24, 2024, Medcalf asked state scientists to redo that study. This, she thought, could validate her and other residents’ belief that toxic exposures were ruining people’s health in Highlands and nearby communities. Surely, Medcalf thought, timid federal and state regulators would then be forced to act.

“THEA has been working in collaboration with local community members since 2011 to develop a more complete understanding of public health in the area,” Medcalf, who now lives in Northwest Houston, wrote in the letter. “In doing so, it is essential to have up-to-date data on cancer rates… throughout the community.”

Medcalf exchanged dozens of emails and phone calls with DSHS scientists throughout the spring of 2024. The agency’s willingness to conduct the study surprised her, given the petrochemical industry’s influence on state government. Acquiring data from the Texas Cancer Registry, which DSHS runs, can be problematic because of the agency’s strict Institutional Review Board and rules related to patient confidentiality.

But the goodwill soured, Medcalf said. By January of this year, the study had been stuck in DSHS’s “executive review” stage for more than six months. Agency scientists gave tight-lipped responses. Medcalf was worried something had gone wrong. Residents were anxious for answers.

Then, on the morning of February 6, the state published the results of its new investigation online. DSHS didn’t notify Medcalf until five days later, on February 11.

At first glance, the only major difference between the 2015 and 2025 studies was their timeframes: 1995-2012 for the first study, 2013-2021 for the second. The new study bore the same name as its predecessor, “Assessment of the Occurrence of Cancer: East Harris County, Texas.” It spanned the same 250-square-mile region along the San Jacinto River. And it unveiled similarly high rates of several types of cancer.

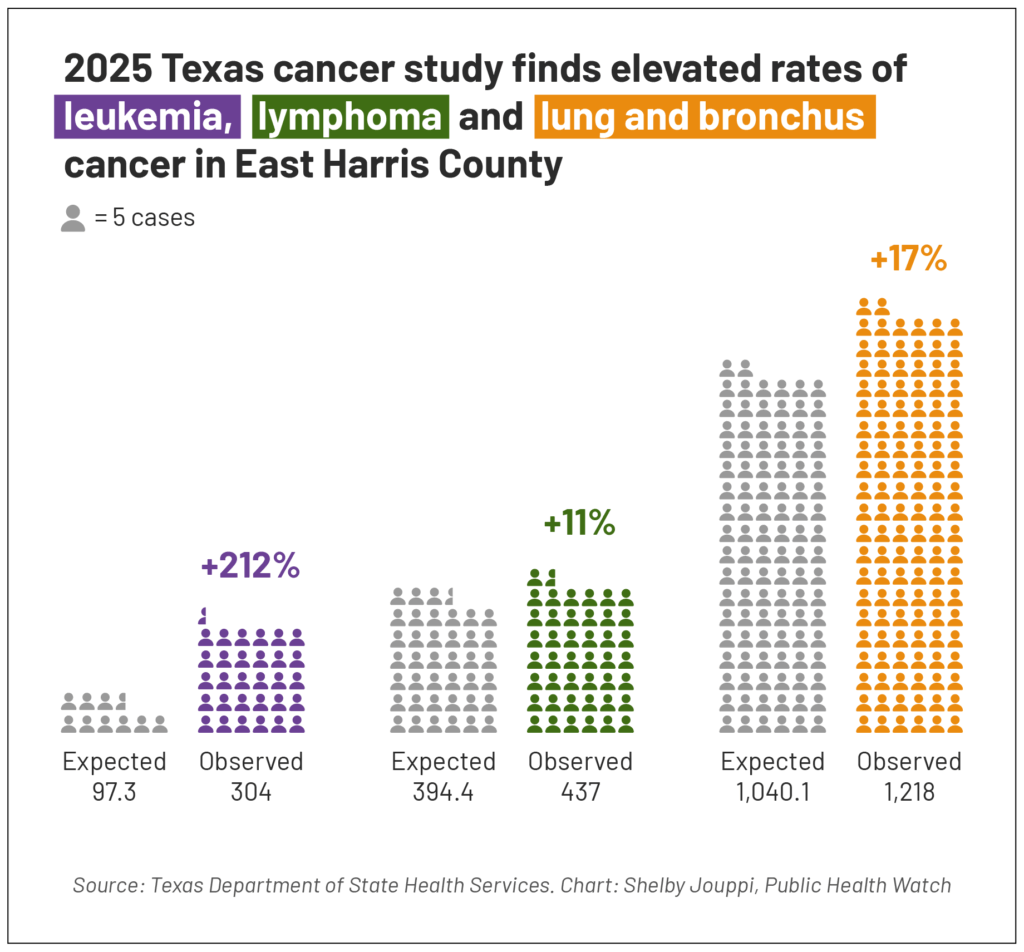

The new investigation examined 22 types of all-age cancers and three childhood cancers. It found that rates of leukemia in the study area were triple the Texas average. Rates of cervical cancer were 18 percent above the state average. Rates of lung and bronchus cancer were 17 percent above the state average. And rates of lymphoma were 10 percent above the state average.

Medcalf said she felt a mix of emotions when she saw these figures.

“At first, I almost felt excited. Finally, some confirmation of the devastating issues that have plagued my family and so many other families. But then reality set in,” she told Public Health Watch. “I was being tested at the time to see if I had leukemia or lymphoma. And there, right in front of me, was a study showing high levels of those exact diseases in the area I lived in for years. I just started crying to my husband, ‘Am I stupid to think I actually made it out of Highlands okay?’”

The studies’ top-level findings were similar. But their nuances differed significantly.

The last paragraph of the 2015 study’s executive summary promised that “DSHS will review these results with a group of subject matter experts to assess the feasibility of follow-up epidemiologic study.” The 2025 study’s executive summary ended by stating that “results should be interpreted with caution, because some of the numbers of observed cancer cases were small.”

The 2015 study also contained a section labeled “recommendations and next steps,” in which DSHS laid out its plans to consult “internal and external experts in epidemiology, oncology, and toxicology, as well as a citizen to represent the community’s interests.” The 2025 study had no such section and made no reference to further research.

One difference stood out: Unlike the 2015 investigation, the 2025 study did not provide any census-tract level information. Patel, the DSHS epidemiologist, said that choice stemmed from a combination of privacy protections and statistical rigor. A DSHS spokesperson said the agency’s scientists didn’t even look at cancer cases by individual tracts.

“If you don’t have more than five cases in a given census tract or area, then you are at risk of producing highly unreliable estimates for cancer incidence rates and ratios,” Patel said. “We are also at the risk of jeopardizing patient confidentiality…. Some of the cancer types are relatively rare cancer types.”

Public Health Watch shared Patel’s assertions with a trio of epidemiologists.

Steenland, the Emory professor, was flummoxed by Patel’s claim, given the overall case numbers in the 2025 study. DSHS expected 1,040 cases of lung and bronchus cancer but found 1,218. DSHS expected 394 cases of lymphoma but found 437. DSHS expected 97 cases of leukemia but found 304. Raw numbers that large are what you want as an epidemiologist, Steenland said.

“Oftentimes when you have far more cases of cancer than expected, it’s because you anticipated finding two but observed 10 instead. Percentage-wise, it’s a huge difference. But the confidence interval is very wide because your sample size is so small,” he said. “Here, the confidence interval is reasonably narrow because the sample size is big.” (According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “confidence intervals are one way to represent how ‘good’ an estimate is.”)

Another expert who reviewed the state data was Philip Landrigan, a pediatrician, public health physician and professor at Boston College who studies the human-health effects of hazardous exposures. He agreed with Steenland.

“You don’t want to release [census-tract] information for a study like this if there’s fewer than five cases,” Landrigan said. “But if you’re talking about lung cancer or leukemia, which is common in the population, then I see no issue whatsoever. You’re obviously not going to release names and addresses, but there’s no reason in the world why you could not release de-identified data.”

Steenland and Landrigan pointed out that the 2015 study didn’t release census-tract level data for every cancer type and every tract. Instead, it only did so when an elevation in the rate of a specific cancer was statistically significant—meaning the result was unlikely to be explained by chance—and exceeded five cases. “For observed case counts less than five, numbers have been suppressed to protect confidentiality,” the study’s authors explained.

Both experts said that breaking down the new study’s data by census tract would have been a simple task. Despite Patel’s claims, they said, the state could have—and should have—released as much census-tract level data as possible. The high rates of lung and bronchus cancer and lymphoma and leukemia suggest a potential link to environmental exposures.

“If I saw those numbers, I’d immediately dig down further and make maps to look for hot spots. Then I’d go out to those hot spots and take measurements for chemicals in the air like benzene, butadiene and other volatile organic compounds,” Landrigan said. “This is a situation where the public needs the information, especially since it was a public agency who did the study. This deserves serious investigation and some kind of remediation.”

Jonathan Samet, the third expert consulted by Public Health Watch, was not as critical of DSHS as the other scientists were, saying Patel “is adhering to her interpretation” of current epidemiological policies. Still, Samet—a pulmonary physician, an epidemiologist and the past dean of the University of Colorado’s School of Public Health—acknowledged that industrial pollution could help explain the three-to-one ratio of observed versus expected leukemia cases.

“Three is high. I mean, period. If you told me that number was higher in proximity to refineries and then went down, that makes sense,” Samet said. “This is an area, by what we know about the industries there, that could have higher exposure to leukemogens. Benzene is something that would be released by a refinery or other chemical plants, so there might be a reasonable basis for concern.”

Confronted with the experts’ opinions, Patel insisted her team’s investigation followed standard practices maintained by DSHS and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including a new “CDC protocol” enacted in 2022. Yes, she said, leukemia cases were three times higher than the Texas average, but that isn’t an “exceptionally high” rate that would warrant “an in-depth epidemiological investigation.” Instead, the best thing to do is to “keep an eye on those types of cancers” in the coming years.

Public Health Watch asked DSHS several times to provide the “protocol” to which Patel referred. In an emailed statement Tuesday, an agency spokesperson wrote, “The 2022 CDC guidelines are not a protocol, they are evidence-based recommendations that state, tribal, local and territorial health departments may consider when responding to inquiries and requests around the unusual incidence of cancer. … The guidelines do not have any specific statement or language requiring or excluding individual census-tract analyses.”

Landrigan, the Boston College professor, had already told Public Health Watch there were no CDC protocols prohibiting the release of census-tract level data. “They’re snowing you,” he said in an email. “It’s BS.”

The person most upset about the state’s decision was Medcalf. Following the study’s release, she went through the nearly 100 emails she’d exchanged with Patel and other agency officials. At no point did Medcalf ask for census-tract level data in writing, she said, but she did ask for it during a phone call with Patel.

Patel never warned her that providing such information was out of the question, Medcalf said. The whole point of her request, she said, was for DSHS to redo the 2015 investigation that provided census-tract data.

In April, Medcalf’s nonprofit, THEA, held a pair of community meetings in East Harris County to inform residents about the study’s findings and shortcomings. Patel and her colleagues were invited to both events but declined to attend—which a DSHS spokesperson attributed to a lack of advance notice and the agency’s busy schedule during the Texas legislative session. THEA set up an empty table with balloons at both meetings to note the agency’s absence.

“For all the months leading up to the study’s release, the state told us they would do community engagement with us. And then they completely reversed course,” Medcalf said. “It’s our community’s health information. Come and talk to us about it. We were all pissed off. We’re all still pissed off.”

Six weeks earlier, Medcalf held a joint press conference with Precinct 3 Harris County Commissioner Tom Ramsey, a Republican who represents Highlands and other communities located in the study area. Before taking office, Ramsey worked as an engineer for companies along the Houston Ship Channel. Cleaning up the Superfund site near Highlands—the dioxin-loaded waste pits buried beneath the San Jacinto River—is one of his top priorities.

On September 8, Ramsey sent a letter to DSHS Commissioner Jennifer Shuford. In it, he urged Shuford to hold meetings with residents about the current study, release an addendum with census-tract level data and commit to follow-up meetings with advocates and local elected officials once that information is released. Three Houston-area Democrats—U.S. Rep. Sylvia Garcia and Harris County Commissioners Adrian Garcia and Rodney Ellis—also sent letters.

Ramsey told Public Health Watch the state’s intransigence is hurting public trust in government.

“I’ve worked directly for 50 cities, 20 counties, and every state agency you can’t name,” he said. “You’re better off getting everything out on the table. Nothing was ever gained by keeping data under wraps. There’s no good reason to withhold it. Buried in that data is probably some severely impacted ZIP codes. I think there’s a relationship between those waste pits and the health issues people have experienced in the region.”

Longtime residents of East Harris County share Ramsey’s sentiment.

Brenda Farmer grew up in a wooded riverside neighborhood in Highlands. She has childhood memories of exploring the area with her now-husband, Joe, and her sister, Sharon Graves. The three of them used to swim in the San Jacinto River, splash around in nearby swimming holes and play on top of strange-smelling trenches of sand. They didn’t know it at the time, but their home was just a few thousand feet from several sources of industrial contamination, including the since-discovered Superfund site.

“Every once in a while, you could see smoke coming up out of the sand. It was sulfur burning. We’d dig it up with a shovel and bring it home and set it on fire, play with it. It felt like a chemistry test,” Joe Farmer said. “We were just kids. We didn’t realize someone had dumped all kinds of chemicals and shit and just covered it with sand.”

In the decades since, Graves and the Farmers have seen dozens of family members, friends and neighbors die of cancer. As an adult, Brenda Farmer was diagnosed with mammary hypoplasia—a condition in which a woman’s breasts have insufficient glandular tissue, often leading to inadequate milk supply for breastfeeding. Her daughter was diagnosed with the same condition. Mammary hypoplasia has been linked to exposure to dioxins.

Graves admitted that no study will remedy the health issues that have broken so many people in her life. But getting location-specific data would force the state to recognize their predicament, she said.

“By only releasing the data from a birds-eye level, you have diluted the information. Two hundred fifty square miles is a giant area,” Graves said. “If you zoom in on that map and show the areas that are actually affected, you will see some cancer clusters, buddy. It’ll be like a map of AT&T’s coverage.”

Michael Bleacher and his wife, Kristen Buster, are just as worried. When the couple decided to move to Highlands in April of 2024, they bought a riverfront home—sight unseen—with a pool, hot tub and big yard. They thought the property would be a retirement paradise where they could boat, fish and watch the sun set. Instead, they’ve spent the last 18 months attending THEA events and meeting with elected officials.

The couple told Public Health Watch their health has deteriorated since they arrived in Highlands. Doctors have tested Bleacher’s blood and warned him about potential signs of leukemia. He’s experienced inexplicable bouts of dizziness. Buster’s hair has started falling out.

If the state releases census-tract level data from its 2025 study, Bleacher’s and Buster’s property could plummet in value. But the couple feels stuck. They believe they were duped into buying a place 1.5 miles from a Superfund site. They say they don’t want to do the same thing to someone else.

“God has put me in every place that I’ve been in my life and has prepared me throughout my life for this exact moment, all the time.” Bleacher said. “We’re really close to our neighbors. We love our church. We love this community. I just want to make things better.”

Buster fixates on her husband’s health.

“I’m a widow,” she said. “I lost my previous husband. I don’t ever want to go through that again. I don’t like being in that club. He handles all our finances, but I’ve asked him to show me every little thing in case something happens.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,