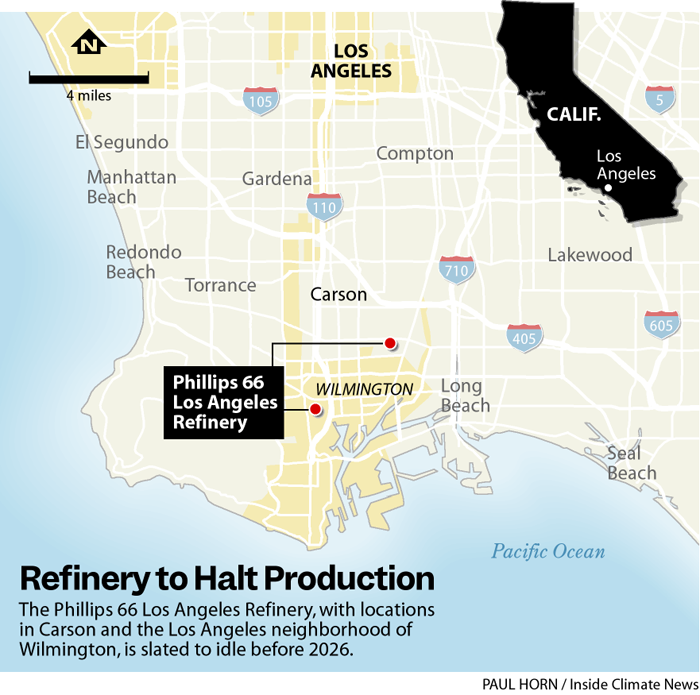

When Morgan Gonzalez first learned, in October 2024, that the Phillips 66 refinery in Wilmington, California, would close at the end of this year, he felt a mix of emotions. For almost 100 years, Gonzalez’s family has lived in the Wilmington community near the Port of Long Beach, suffering from asthma and other respiratory issues that they attribute to truck traffic and the five refineries that surround the small neighborhood.

“I don’t want to understate the impact that this refinery closure will have for our health,” said Gonzalez, an advocate with the environmental justice group Communities for a Better Environment (CBE). “It’s a big change for the community.”

But his excitement has been largely overshadowed by concerns about how the cleanup will proceed.

The refinery sits atop a subterranean “lake of hydrocarbons,” buried hazardous waste and groundwater contaminated with toxic chemicals like benzene, tertiary butyl alcohol and PFAS that have seeped into nearby aquifers. Phillips 66 has yet to disclose the full costs for water and soil remediation and whether it has set aside the funds to cover them.

That worries Gonzalez, especially because of plans already underway to develop the 444-acre Wilmington refinery site into a complex that would include warehouse storage, a shopping center with dining options and sports facilities.

“Once we break ground, what are we going to find, and how will that impact our health?” he asked. “As of right now, the refinery doesn’t have a clear plan for how it’s going to remediate that land.”

Owners of other energy infrastructure, like nuclear reactors, oil wells and wind farms, are required by their regulators to formulate decommissioning plans in order to operate, said Ann Alexander, an environmental consultant who released a new report Tuesday on the risks posed by Phillips 66 and other California refineries as they shut down. In many cases, they’re required to provide financial assurances up front to cover cleanups.

“Refinery closures are badly regulated compared to other industries,” said Alexander, who was previously a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council for 17 years. “The extent of the contamination, the magnitude of the cost of cleanup and the source of funds to pay for it are pretty black boxed right now.”

Alexander talked to dozens of state and local agency staff, community members and experts in refinery operations for the new report commissioned by CBE and the Asian Pacific Environmental Network. She reviewed publicly available documents as well as those acquired through Public Records Act requests.

While Phillips 66 estimated $205 million in refinery closure expenditures in its Securities and Exchange Commission filings this year, Alexander found those only appear to cover the removal of infrastructure and asbestos. The company’s filings didn’t mention the long-term costs of soil and groundwater remediation.

There’s a lot of remediation to be done. In 1994, the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board (LARWQCB) overseeing most of the Phillips site’s remediation ordered the company to remove the pollution at the site, which at the time included pools of hydrocarbons sitting on the surface of the aquifer, the largest of which was up to 13 feet thick covering an area of 6 million square feet. The contamination also included sludge containing lead and acid that had been buried on-site from 1940 to 1977, and extensive pollution of groundwater and soil with toxic and carcinogenic chemicals. More recent investigations have found high levels of PFAS in the groundwater at the refinery’s Wilmington and Carson sites.

The work to pump out the pollution has been going on since the 1980s, but the water board said it could take years more to complete. In September, Phillips 66 submitted a “framework for ongoing remediation efforts” at the Wilmington site to the board, where it noted that it would not begin demolishing the refinery until its redevelopment plan was approved and that shallow and deep soils remediation would be assessed at later dates.

In a statement to ICN, Phillips 66 said it has made “significant progress” removing contaminants and that “future redevelopment of the properties and removal of refinery equipment will allow additional investigation and cleanup activities, including cleanup of impacted soils.”

The water board said that as of the end of 2024, about 800 thousand gallons of refinery products like diesel fuel and oil, and 17 million gallons of impacted groundwater had been removed, but that it did not have an estimate of the cost of full remediation or the timeline.

“Idling of the facility provides an opportunity to expedite the assessment and remediation of areas that were not accessible during refinery operation,” said spokesperson Ailene Voisin in a statement. “Additional assessment is ongoing to identify what additional contamination remains.”

The board’s process to determine the right level of remediation after a closure may work in some situations, said Alexander, but it creates a problem for communities and agencies that must plan ahead for large-scale cleanups. Further complicating matters is the fact that refineries, which when they shut down are technically on the hook to pay to remediate the land and water they’ve contaminated, aren’t required to set aside money in advance to cover the cost of their closure.

“What do you do if they declare bankruptcy and go away?,” asked Alexander, noting the case of a refinery in Philadelphia that went bankrupt after a major explosion in 2019, shut down and left decades-worth of toxic leaks and spills unaddressed. “This isn’t an imaginary concern.”

Gonzalez raised the case of the Carousel neighborhood in Carson, where residents who moved in in the early 2000s experienced cancers, asthma and blood disorders after being exposed to benzene and other chemicals left behind from Shell oil storage tanks. Shell claimed it was the developer’s responsibility to clean them up.

Phillips 66 sits on land with high development value near the port and it’s likely that the two real estate developers the company has engaged, Catellus Development Corporation and Deca Companies, will play a role in the site’s remediation.

The developers have already proposed a project for the site that would include an industrial logistics center on the southern portion of the site and a retail and restaurant development in the north, along with playgrounds and playing fields.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe refinery’s September work plan, yet to be approved by the water board, said that shallow soil remediation would be addressed “by the prospective purchasers” and would be evaluated through the project’s environmental impact report. It noted the developers would be seeking voluntary cleanup agreements with the state, which developers commonly pursue in exchange for immunity from future liability. The developers did not respond to a request for comment and Phillips 66 did not share details about any potential arrangement to share cleanup responsibilities.

“Phillips 66 will remain responsible for any contamination stemming from operations of the refinery under state and federal law,” said spokesperson Al Ortiz in a statement.

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) review of the project, called Five Points Union, is already underway and will require a full environmental impact report and zoning changes. The City of Los Angeles held public scoping meetings in August and Phillips 66 said the review process will take several years and include many additional opportunities for public input.

But Gonzalez says the proposal, put together and submitted before a state-led public input process, could limit other developments the community may have wished to see.

“It’s really full steam ahead, and they have their plans laid out,” said Gonzalez.

That’s why Alexander recommends that going forward, local governments in communities with refineries seek public input ahead of any closure and proactively re-zone the property to reflect their desired future uses.

Also among the Alexander report’s recommendations: mandating decommissioning plans and full disclosure of refinery remediation costs prior to closure announcements, developing default standards for refinery clean up and creating taxes and independently managed funds that refiners would pay into to cover their costs of closure.

As Phillips 66 moves toward idling at the end of the month, worker safety has increasingly become an issue. The refinery closure announcement spurred many workers to seek other jobs, and as of August, about a quarter of union employees had already left, leaving the remaining staff to work 12-hour shifts in 13 days on and one day off rotations, increasing their risks of exhaustion and accidents.

To that end, the report recommends that the state create new safety provisions specific to refinery wind downs that take into account employee loss and prioritize worker retention through things like extended severance periods and job training. Even if Phillips 66 goes idle at the end of the month without any major incident, workers at refineries closing in the future will likely face similar pressures.

Last fall, Valero’s announcement that it would close its refinery in Benicia next year sent lawmakers and regulators into a panic. The Phillips 66 refinery and Valero’s Benicia facility together represent nearly 20 percent of state refining capacity. Facing potential gasoline shortfalls that could drive up fuel prices, California leaders pivoted from railing against the oil industry to taking emergency measures to support refineries and stabilize their operations. They put off a decision on a potential profit cap, streamlined the permitting of new oil wells in Kern County and at one point discussed bailing out the refineries by covering the cost of expensive turnaround procedures in which refineries shut down to perform essential maintenance.

Despite the change in tone and policy on refineries and the federal support for oil, Alexander is certain more closures are coming.

“In the medium to long term, [oil] demand is declining nationwide,” said Alexander. “It’s not plausible that all of the refineries that are open now are going to remain open. So we have an opportunity now to plan for this in advance.”

This story has been updated to include comments from Phillips 66 and the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,