GRAND JUNCTION, Colo.—It can carry life-threatening diseases. It’s difficult to find and hard to kill. And it’s obsessed with human blood.

The Aedes aegypti is a species of mosquito that people like Tim Moore, district manager of a mosquito control district on the Western Slope of Colorado, really don’t want to see.

“Boy, they are locked into humans,” Moore said. “That’s their blood meal.”

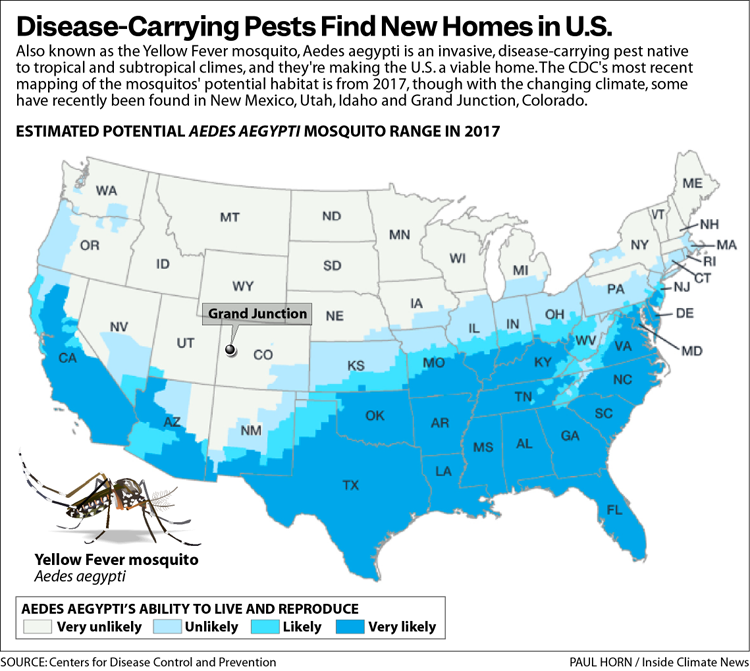

This mosquito species is native to tropical and subtropical climates, but as climate change pushes up temperatures and warps precipitation patterns, the Aedes aegypti—which can spread Zika, dengue, chikungunya and other potentially deadly viruses—is on the move.

It’s popping up all over the Mountain West, where conditions have historically been far too harsh for it to survive. In the last decade, towns in New Mexico and Utah have begun catching Aedes aegypti in their traps year after year, and just this summer, one was found for the first time in Idaho.

Now, an old residential neighborhood in Grand Junction, Colorado, has emerged as one of the latest frontiers for this troublesome mosquito.

The city, with a population of about 70,000, is the largest in Colorado west of the Continental Divide. In 2019, the local mosquito control district spotted one wayward Aedes aegypti in a trap. It was odd, but the mosquitoes had already been found in Moab, Utah, about 100 miles to the southwest. Moore, the district manager, figured they’d caught a hitchhiker and that the harsh Colorado climate would quickly eliminate the species.

“I concluded it was a one-off, and we don’t have to worry too much about this,” Moore said.

But then, a few years later, it happened again. They found two more of the invasive mosquito species in traps in 2023.

“Coincidence is not a word you use much in science,” said Hannah Livesay, biologist at the Grand River Mosquito Control District, which is based in Grand Junction.

The team bought different traps and adjusted their techniques to hunt for the mosquito. Scientific literature and mosquito researchers told them the effort was bound to be pointless. It was unlikely the mosquito would make it through the winter.

Then, the results started coming in. In 2024, the first year of the Aedes aegypti surveillance program, the district caught 796 adults and found 446 eggs.

These mosquitoes weren’t just surviving in Colorado—they were thriving.

Dengue Virus Driven by Mosquitoes’ Expansion

Mosquitoes are often called the most dangerous species on the planet for their ability to spread life-threatening diseases to humans. Of those, malaria, carried by female Anopheles mosquitoes, has long been one of the most devastating.

However, as climate change allows the Aedes aegypti to move northward, survive at higher elevations and stay active for longer into the fall, dengue virus is fast emerging as one of the most dangerous of the world’s diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks, researchers say.

Between 2000 and 2024, dengue cases reported to the World Health Organization increased more than twentyfold, as climate change, urbanization and global travel and trade pushed the mosquito vector for the disease into new areas. Climate change has also lengthened the season during which the insect can breed and thrive in areas where it’s endemic. About half the world’s population is now at risk of dengue, according to the WHO, and between 100 and 400 million infections occur each year.

The virus is often mild or asymptomatic, but for some people, it can become severe, so painful that it’s nicknamed “break-bone fever.” It can even be deadly. More than 2,500 dengue-related deaths have been reported globally in 2025, with outbreaks in Brazil, India, Australia and other countries. In the U.S., dengue is most common in Florida, where the Aedes aegypti mosquito has thrived for centuries in the subtropical and tropical climates.

In Colorado, state medical entomologist Chris Roundy said that while the mosquito is in Grand Junction, the state’s public health officials are not too worried about disease spread—yet.

“The presence of those mosquitoes does not mean that dengue is going to be there,” Roundy said.

For the mosquitoes to spread disease, they need to feed on a human who is already sick: Someone who traveled to Florida, contracted dengue and then returned to Grand Junction while they’re still infected, for example.

In other words, the chances of an outbreak of dengue or another of the diseases the Aedes aegypti carries in western Colorado remain pretty slim. Still, he said, “we are keeping a very close eye on [the mosquitoes] to see if they expand their area in Grand Junction, or if we start seeing them in other counties.”

The Hunt for Aedes

On a warm and sunny October morning in Grand Junction, David Garrett, team lead for the Grand River Mosquito Control District’s Aedes aegypti program, parked his white truck on what the team calls their “epicenter street” in the old residential neighborhood of Orchard Mesa, where the Aedes aegypti found a foothold in Colorado.

It was collection day.

Across the rest of Colorado, mosquito control operations aimed at preventing the spread of West Nile virus are winding down. Populations of the native Culex tarsalis mosquitoes, the primary vector for the virus, were declining rapidly in the autumn chill.

But in Grand Junction, Garrett is still in the field looking for the invasive mosquito species that seems to get active in the fall.

David Garrett, team lead for the Grand River Mosquito Control District’s Aedes aegypti program, traps mosquitoes in the Orchard Mesa neighborhood of Grand Junction, Colo.

The traps need to be close to humans—the food source—and an inviting place for the mosquitoes to lay eggs. Unlike the mosquitoes that are native to the Western Slope, which breed in standing water like ditches and ponds, the Aedes aegypti mosquito prefers to breed in containers like potted plant saucers, watering cans and decorative yard fixtures. The traps for them look like unassuming black plastic buckets with an oddly shaped funnel attached to their tops. The district has snuck them into corners of front yards, between bushes and along fences throughout the neighborhood.

Garrett plucks out the sticky papers that have been inside the traps for the previous week, replaces them with clean sticky papers and adds a bit of fresh water. He’ll take the samples back to the lab to count how many Aedes aegypti they snagged.

But before doing that, he paused to peel one of the sticky papers apart and counted four invasive mosquitoes stuck to it. Their jet black bodies with reflective white markings are easy to differentiate from the dusty brown of the native desert mosquitoes.

As of mid-October, the district had caught 526 adult Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in 2025, all in the Orchard Mesa area.

The mosquitoes don’t lay all their eggs in one basket. They skip from container to container, laying a few eggs in each. “You don’t find one and find them all,” said Livesay, the district’s biologist. “So, it’s really difficult to track them down.”

Back in the car, control district staff wound through the neighborhood. From the passenger seat, Livesay pointed with a frustrated sigh at an old tire lying in a yard. “Tires are one of the most common places you find them,” she said.

The species’ preference for backyards and gardens makes it incredibly difficult to control, Livesay said. The district had to get permission from dozens of homeowners in the Orchard Mesa area to set up and maintain traps on private property, and only a handful of homeowners have allowed them to spray insecticides in their yards.

“You don’t find one and find them all. So, it’s really difficult to track them down.”

— Hannah Livesay, Grand River Mosquito Control District

Public awareness of the mosquito’s presence, and the potential health risk it could pose, has been gradual; the district has passed out fliers and chatted with residents, but the campaign doesn’t appear to have quite taken root. On the day the team checked its traps, several residents said that they weren’t aware that an invasive mosquito was present in their neighborhood.

The new species is also expensive to control: It has cost the district about $15,000 this year in new traps, additional staff who must stay later into the season and different insecticides after learning that the mosquitoes had a resistance to the one they use for the native mosquitoes—permethrin.

Given how costly it is to control them, further expansion of their range on the Western Slope is Moore’s biggest concern. Right now, the Aedes aegypti occupies about 100 acres of the Orchard Mesa neighborhood. He doesn’t want it to gain any more ground.

“If we can’t get rid of them, or at least confine them,” Moore says, “that’s a huge game-changer for us.”

“We Need a Cold Winter”

While it’s virtually impossible to know how the mosquitoes got into Colorado, experts said, the pathway could’ve been as benign as a Grand Junction resident bringing home a potted plant from out of state.

Robert Hancock, a mosquito researcher and biology professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver, said that, since the mosquito follows humans and is easily transported by the containers it breeds in, he’s not surprised when it pops up in Colorado and other high and cold locations. What does surprise him is when the mosquito can survive winters in those areas.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowHancock noted it’s recently been found to endure the winters in Utah, California and Oregon—and now in Colorado.

“That’s the scary part, because it made it to the next summer in Grand Junction,” Hancock said, speaking in his Denver lab while feeding his own colony of Aedes aegypti, reared for research. (He allows the mosquitoes, which are completely free of disease, to feed on his own arm.)

As the climate warms, Hancock said, “Aedes aegypti is performing at an extraordinarily high level.”

More than half of pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change, a 2022 article in the journal Nature Climate Change found.

Livesay, the biologist, suspects the newcomer mosquitoes are wiggling their way into basements and greenhouses to weather the Colorado winter, which doesn’t have as many freezing nights as it used to.

Grand Junction had only 17 days of below-freezing temperatures in 2024, the fewest on record, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Typically, the area gets more than two months’ worth of freezing weather. Winters there have, on average, warmed 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1970.

“We need a cold winter for the mosquitoes to not make it through,” Livesay said. “Things are hovering just above freezing, and they’re able to last.”

This story was produced with support from the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,