Forever War, Part 2: This story is published in partnership with WHQR, a nonprofit radio station and NPR affiliate in Wilmington. It is the second in a series of stories about the PFAS crisis in North Carolina.

The shipment arrived by FedEx, packed in dry ice. Inside were 119 plastic vials, each containing three drops of blood that had been stored at minus 112 degrees Fahrenheit for as long as a decade.

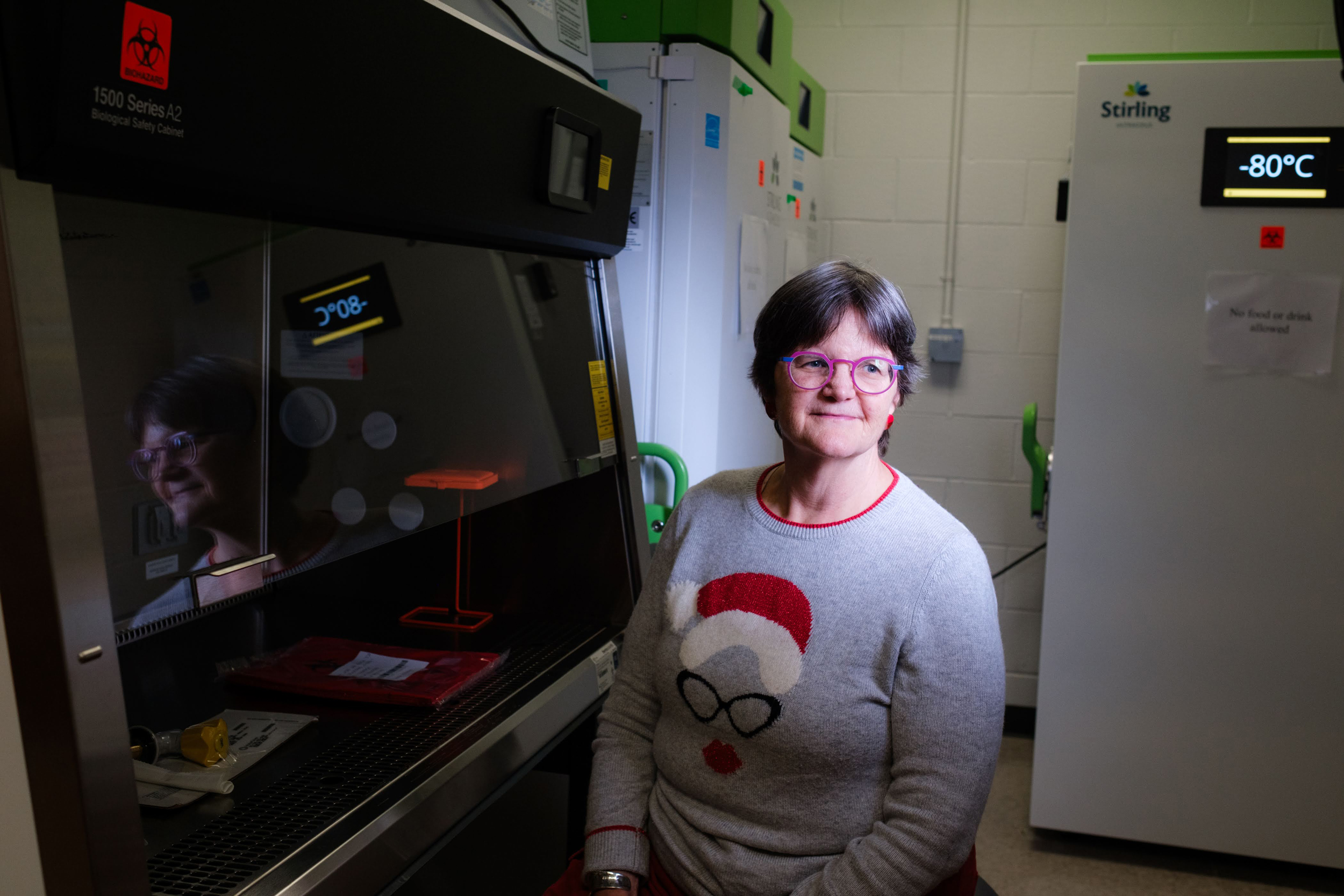

Jane Hoppin, an environmental epidemiologist at N.C. State University had ordered the blood. From 2010 to 2016, Wilmington residents had donated their serum to a biobank run by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to help scientists better understand how the body works. Now Hoppin wanted to learn if high concentrations of PFAS in the city’s drinking water were also present in the donors’ blood.

However, Hoppin and her fellow scientists didn’t anticipate finding one type of PFAS compound: TFA. The chemical industry has touted its toxicity as being “of lower concern,” because it breaks down quickly in the body.

Yet there it was, TFA, in five-year-old water and blood.

“We were surprised,” Hoppin said. “No one expected this.”

Hoppin was born in northern California and grew up in Cincinnati, about 200 miles west of a DuPont factory that discharged PFOA, a chemical used in non-stick cookware, into the Ohio River.

Even as a very young child she was interested in chemicals and their effects on human health.

When Hoppin was 4, her mother took her to a school psychologist to determine whether she could enter kindergarten a year early. The psychologist asked Hoppin to draw a person. When she finished, the psychologist seemed alarmed and recommended she stay home another year.

The people in her drawings had no nose or mouth.

“My mom said, ‘Why didn’t you draw a nose or a mouth?’” Hoppin recalled.

It was 1968, two years before Congress established the Clean Air Act, and Hoppin had recently seen television footage of smoggy Los Angeles.

She remembers telling her mom, ‘Well, I didn’t want them to breathe the air.’”

Now Hoppin feels the same way about people drinking water from the Cape Fear River.

Because many labs were closed during the pandemic, the Wilmington study took five years, but in October Hoppin and her colleagues at N.C. State and UNC released the results. All of the blood samples contained at least one of 34 toxic chemicals known as PFAS, including some used in fluorochemical manufacturing at Chemours, 80 miles upstream in Fayetteville.

More than three-quarters of the Wilmington blood samples contained elevated levels of TFA, whose health and environmental effects aren’t fully understood.

The study included archived samples of the Cape Fear River and Wilmington’s drinking water. They also contained elevated levels of more than two dozen PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, including TFA.

There are no federal or state drinking water standards for TFA.

Hoppin knew that It would not be unusual to find certain types of PFAS in the water and blood samples. In particular, PFOA and PFOS, known as “long-chains” because of their molecular structure, are notoriously persistent and linger in the environment for hundreds of years. In the human body, it can take more than a decade to eliminate them.

But TFA is an ultra-short chain compound. That the blood still contained such high levels of TFA suggested that the donors were being exposed to the compound, not just from Chemours, but by a variety of sources that scientists are only becoming aware of.

The troubling results opened a new front in a decades-long battle North Carolina environmentalists have been waging against PFAS in the state’s drinking water and air, soil and food.

PFAS Are Everywhere

There are tens of thousands of types of PFAS, which are found in many consumer products,as well as water-resistant clothing, furniture and personal care products. The compounds are ubiquitous, contaminating air, drinking water, fish, soil, crops, eggs and milk worldwide. PFAS even contribute to climate change by disrupting the ocean cycle and increasing the emissions of greenhouse gases.

PFAS exposure can lead to myriad serious health conditions, including kidney and testicular cancer, thyroid disorders, reproductive problems, high cholesterol and a depressed immune system.

In 2024, they celebrated when the Environmental Protection Agency under former President Joe Biden finally enacted the first drinking water standards for PFOA, PFOS, GenX and three other related compounds.

But their victory was short-lived. During President Donald Trump’s second term, the EPA has weakened or gutted its few PFAS regulations. The agency has delayed implementation of drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS by two years, until 2031.

In September it also petitioned the U.S. Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia to rescind drinking water standards for several compounds, including GenX, which Chemours uses to produce non-stick cookware, food packaging and firefighting foam.

The government shutdown earlier this fall delayed the court case. Lawyers for the agency and opponents of the rollback are scheduled to file additional legal briefs this month.

As the chemical industry applauds the rollbacks, Chemours is planning to expand its Fayetteville Works plant, the source of GenX and dozens of similar compounds, including TFA.

The company doesn’t make TFA in Fayetteville, but its presence in the river and the air illustrates a stubborn aspect of the ubiquitous compounds: PFAS precursors.

There are thousands of such precursors, substances that, under certain conditions, transform and break down into a different PFAS compound. Like wood is a precursor to ash, and iron to rust, the compound PAF degrades and becomes TFA.

Chemours told state regulators in February that “based on risk assessment modelling and available toxicological data for similar compounds, TFA is not believed to be harmful to human health or the environment.”

The N.C. State study and other research calls into question Chemours’ assertions that TFA is benign. The compound is widespread in the environment, and even though it breaks down relatively quickly in the body, people rapidly absorb it from their food, drinking water and air.

Hoppin and Duke University scientists found in a separate study released earlier this year that the compound was present in house dust.

When TFA and other ultra-shortchain compounds accumulate in the body, according to the N.C. State study, they “can reach very high levels,” potentially harming human health.

Earlier this year the German government proposed classifying TFA as toxic to reproduction, including impaired fertility and harm to the fetus.

“We’re piecing together the past,” Hoppin said. “But the real concern is that we continue to measure exposure in people today.”

High Levels of TFA

N.C. State scientist Detlef Knappe was failing at taking his sabbatical. This fall, between globetrotting trips to Australia, Singapore and beyond, he was proofreading and finalizing the Wilmington blood and drinking water study.

Knappe had played an outsized role in the protests that led to the EPA’s drinking water standards for several types of PFAS. He was among the scientists who, in 2015, discovered GenX in the Cape Fear River and Wilmington’s drinking water. Those findings launched an environmental movement, with thousands of North Carolinians urging the EPA to regulate GenX and other PFAS in drinking water.

As part of that research, Knappe had stored samples of river water and drinking water in case he wanted to reanalyze them in the future.

In 2024, that time came.

The collection date of the water and blood samples was critical. To fully understand the extent of residents’ PFAS exposure, Hoppin and Knappe needed samples taken before June 2017, when state regulators forced Chemours to stop discharging the compounds into the river.

Knappe retrieved samples from one day in late May 2017, when he and his colleagues had collected water from 10 spots in the river: upstream and downstream of Chemours, in Wilmington and at the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, which provides drinking water for nearly 200,000 people.

The study found that concentrations of TFA in the Cape Fear River immediately downstream of Chemours reached 6 million parts per trillion, “orders of magnitude” higher than in upstream samples. This suggested Chemours was a significant source of the compound at these locations.

By the time the TFA reached Wilmington and passed through the utility’s water treatment plant, the levels were still extremely high: 108,000 parts per trillion.

That’s equal to 50 times the health guidance level of 2,200 ppt set by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. It is also above the German Federal Health Agency’s advisory of 60,000 ppt; Germany considers TFA to be toxic to reproduction.

“The overwhelming evidence is that these compounds are of concern,” Knappe said. “I’m very concerned that we’re not going to get TFA under control in the time that is needed to prevent adverse health outcomes.”

A “Regrettable Substitute”

TFA is what scientists refer to as a “regrettable substitute,” because in trying to solve one environmental problem, it creates another.

In 1985, the problem was an enormous hole that researchers had discovered in the Earth’s ozone layer, which shields the planet from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. The culprits were chlorofluorocarbons, also known as CFCs, used in refrigerants in common appliances, such as air conditioners.

Not only were CFCs exfoliating the Earth’s protective skin, they were also contributing to climate change. Two years later, companies began phasing out CFCs under an international treaty, the Montreal Protocol, and replaced them with other substances that in the atmosphere can transform into TFA.

Since then, TFA has become baked into modern life. When Prozac, the antidepressant taken by 5.7 million people in the U.S., breaks down in water, it forms TFA.

At data centers, the AI that drafts emails, mines cryptocurrency and analyzes medical scans requires enormous computing power. To prevent the computers from overheating, data centers use cooling fluids, some of which emit chemicals that become TFA. Chemours makes such a product at its plant in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Dozens of pesticides also contain TFA, including one recently approved by the EPA to kill insects on corn, soybeans, wheat and citrus. The pesticide, called isocycloseram, is also approved for home lawns and to kill cockroaches, termites and bedbugs.

The planet is so bombarded with TFA that, since 2010, global levels have increased as much as 17 times compared with previous decades, according to Scandinavian scientists. They warned that TFA could cause “potential irreversible, disruptive impacts on vital earth system processes.”

“We went from compounds that destroyed the ozone layer,” Knappe said, “to compounds that break down and pollute the earth with TFA.”

What’s Coming Out of Chemours Now?

One day in late September, Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette paddled his aluminum rowboat toward the Chemours Fayetteville Works plant. The N.C. State scientists were finalizing their study, but their findings would show only a snapshot of Chemours’ past discharges. Burdette wanted to know how much TFA and other ultra-short chain compounds Chemours was currently sending into the river.

He dipped a sampler into the water near Outfall 2, where the company discharges treated wastewater unrelated to its manufacturing. He continued downstream to the boat ramp below the Huske Dam. There, he collected water entering the Cape Fear via a seep, then rowed to Outfall 3, to grab more water leaving the southern edge of the plant.

Burdette returned to Wilmington, where he collected drinking water from a tap, and then a second one in nearby Brunswick County.

The results were disturbing: Water leaving Outfall 2 had concentrations of 14,950 ppt of TFA; discharge from Outfall 3 contained 21,900 ppt.

Near the dam, TFA concentrations reached 148,513 ppt. There were high levels of other ultra-short chain compounds, as well.

Downstream, TFA was penetrating the $80 million advanced filtration system the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority had installed to remove GenX. The drinking water Burdette collected at a Wilmington tap contained TFA at concentrations of 1,900 ppt; levels at the Brunswick County tap were 1,400.

Both results are below the Dutch health guidance level of 2,200 ppt in drinking water.

“It is unfortunate, though unsurprising, that we continue to see the impacts from Chemours’ decades of PFAS releases from their chemical manufacturing plant on the Cape Fear River,” said utility spokesman Vaughn Hagerty. “Chemours continues to shift the ever-growing, multimillion-dollar burden for addressing its PFAS contamination to downstream water users.”

Burdette’s findings bolstered concerns raised by Southern Environmental Law Center about the plant’s TFA discharges, especially in light of the planned expansion.

SELC is urging the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to require Chemours, as part of its pending wastewater discharge permit, to sample for TFA and other ultra-short chains in Outfall 3. DEQ should then limit the amount of TFA that enters the river, SELC wrote.

Legally, if the DEQ doesn’t implement limits for TFA and other ultra-short chains, then Chemours could try to argue that those pollutants are permitted, SELC attorney Jean Zhuang told Inside Climate News. “That risks shielding them from liability for releasing them. It is really important that the state acts on these pollutants.”

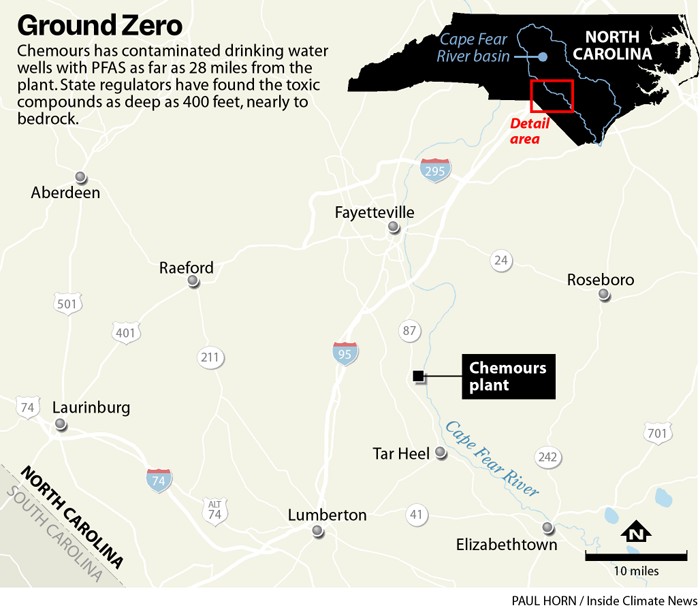

The recent findings also raise questions about whether TFA is in private drinking water wells. A 2019 consent order among Chemours, Cape Fear River Watch and DEQ requires the company to test wells near the site for more than a dozen types of PFAS. However, TFA is not on the list.

“We don’t know if it’s in wells,” Hoppin said. “They need to be re-analyzed the samples for TFA.”

The program is voluntary. So far, 22,000 private wells have been sampled, and of those nearly 7,500 households have qualified for alternate water supplies as stipulated in the consent order.

A DEQ spokesperson said that the agency is weighing options to add TFA to its environmental monitoring. That would require a separate laboratory method outside those established by the EPA.

Since there is no regulatory drinking water standard for TFA, the spokesperson said, DEQ “does not have an alternative water recommendation to offer at this time.“

Chemours’ Expansion

The Chemours plant fans out over 2,100 acres flanked by N.C. Highway 87 and the Cape Fear River in northern Bladen County, about 15 miles from Fayetteville. A dozen straight roads and a railroad spur run through the property and impose order on the cacophony of tanks and pipes and smokestacks.

Those smokestacks emitted 267 pounds of TFA in 2021, according to documents accompanying the company’s air permit application. Once released, TFA floats through the air, falls to the ground and contaminates all that it touches.

A Chemours spokesperson told Inside Climate News even though the company would increase production of PFAS after the expansion, fluorinated organic compound emissions, which include TFA, to the air are still “projected to decrease by an average of 9 percent compared to the 2021 baseline.”

In its 2024 permit application, Chemours says indoor, outdoor and process emissions—those released directly from manufacturing and waste management—would decrease by 1,765 pounds per year.

But Zhuang of SELC said that claim is misleading. Accounting for maximum potential PFAS emissions from different product lines, the 2024 permit application shows a potential increase of 20 percent, or 2,500 pounds per year.

However, Chemours’ 2025 application shows significant decreases in PFAS air emissions, although those don’t account for the maximum possible.

The company has based some of its air emissions estimates on the demand for Chemours products. State records show DEQ, in reviewing the air permit application, recently asked Chemours for additional information over concerns about the use of “market conditions” as a basis for calculating potential emissions, as well as other inconsistencies.

“That’s not a reliable estimate of their actual potential emissions,” Zhuang said.

The Chemours spokesperson said that due to the “operational limitations of Vinyl Ether manufacturing units, the emissions potential hinges on how much of each product the company manufactures, which can vary.”

Chemours has also set a goal of reducing PFAS emissions and discharges by 99 percent globally by 2030, according to the company’s sustainability report released last year. Since 2018, Chemours says it has cut global PFAS emissions and discharges by three-quarters.

Ralph Mead, a professor of Earth and Ocean Sciences at UNC Wilmington, is an affable man who dresses casually, like a lot of people who live in beach towns. He specializes in understanding how contaminants travel through the air and where they land, a phenomenon known as atmospheric deposition.

On a humid and breezy September day, outside Mead’s lab between a parking lot and a marsh, he and a graduate student, Justin Parker, peered into a white bucket to see if it had collected rain overnight.

Similar to other PFAS compounds, when TFA is emitted into the air—from a refrigerator, a heat pump, a smokestack—it can travel hundreds of miles in different directions before it falls to the ground—or into a bucket.

If it had rained, Parker would inject the water through a labyrinth of instrumentation to analyze it for dozens of types of PFAS. The bucket was empty. But previous rainwater sampling had found very high levels of TFA, its origins likely varied, but unknown.

In Mead’s view, that’s the issue with Chemours’ air permit application: It doesn’t fully account for the long-range dispersion of the compounds, including TFA.

DEQ required Chemours as part of its application to show that increased PFAS production at Fayetteville Works would not increase the atmospheric deposition of the compounds coming from the facility.

State regulators wanted to avoid a repeat of what had happened with GenX: For more than a decade, Chemours emitted tons of the contaminant from its smokestacks. It fell to the ground and contaminated the soil, river and drinking water wells at least 28 miles away.

Chemours hired a contractor to study how PFAS would behave in the air. The analysis separated the compounds into “depositable”—meaning they can chemically transform and land nearby—and “non-depositable”—which would linger in the atmosphere for years and float far away.

The contractor’s report concluded that depositable emissions, including TFA, would total 1,700 pounds, an 11 percent reduction from 2021 estimates.

Non-depositable emissions would decrease by 15 percent, to 9,300 pounds.

Mead read the contractor’s study and said he still has questions about the fate of the non-depositable compounds. “We need to account for those,” he said. “It’s important for human exposure aspects, as well as contamination of the surface of the Earth away from the facility.”

Mead and scientists from four other public universities in North Carolina will soon launch a three-year study on the behavior of PFAS in air leaving the Chemours plant. The research, paid for by the N.C. Collaboratory, which funds academic research in the state, will include analysis of how the compounds transform in the atmosphere and their deposition patterns when they fall to the Earth’s surface.

“This information may allow for better enforcement and regulation of these compounds from the facility,” Mead said.

Environmental advocates say the air permit application is yet another example of the company’s lack of transparency about its operations, transgressions documented in state and federal records.

In 2023, with EPA approval, the company imported GenX from its plant in Dordrecht, the Netherlands, but never informed state regulators.

Three years earlier, DEQ cited the company for dumping soil and tree roots likely contaminated with PFAS into an unlined landfill. In 2017, Chemours failed to report a chemical spill at the plant.

And in the early 2000s, state records show when Chemours’ parent company, DuPont, told DEQ it was manufacturing GenX, it didn’t disclose that it was discharging the compound into the river.

Since Chemours has failed to clean up its existing and widespread contamination from Fayetteville Works, Zhuang told Inside Climate News, the facility “is absolutely not a place where the company should even be contemplating expanding its manufacturing operations.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowMore recently, Chemours has kept under seal thousands of pages of information about the compounds, including health effects, as part of a federal lawsuit filed against the company by the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, Brunswick County and the Town of Wrightsville Beach.

Lawyers with SELC filed a motion with the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District in North Carolina, to intervene in the case, arguing the public has a First Amendment right to the information.

“After contaminating the drinking water, air, soil, and food for more than half-a-million North Carolinians for decades,” SELC’S motion reads, “the companies have no right to conceal essential documents related to their own pollution, including information on sampling data, air and wastewater treatment options, toxicology, and the public’s exposure to their toxic chemicals.”

The Southern Coalition for Social Justice filed a similar motion as well.

The company previously argued in court documents that the sealed material contains confidential, proprietary information. On Dec. 3, U.S. District Court Judge James Dever, who was appointed by President George W. Bush, ruled against Chemours. Dever wrote that the company’s “move to seal a broad class of documents they deem commercially sensitive or confidential do not provide specific evidence to support their motion.”

Warnings in an Empty Room

On the evening of Nov. 5, nearly every metal chair was empty at the Wilmington City Council meeting. Burdette, dressed in a slate gray button-up shirt and olive pants, his eyeglasses perched on his head, urged the council to pass a resolution opposing Chemours’ expansion.

Burdette noted that his two children drank the water for years before they knew it was contaminated, and that his father died of kidney cancer, which is linked to PFAS exposure, especially GenX.

“This resolution is our City Council saying it won’t tolerate the continued contamination of our air and water,” Burdette told the six-member council and mayor. “It tells DEQ that our leadership expects the state to do its job and protect the people and the environment. The expansion is a slap in the face to Wilmingtonians.”

The City Council unanimously passed the resolution. The next week, on Nov. 12, the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority board did the same, followed by the New Hanover County and Brunswick County Commissioners.

A Chemours spokesperson said the company “respects Wilmington City Council’s and Cape Fear Public Utility Authority’s right to express their opinions, though it seems counterintuitive to oppose a permit application that would ultimately reduce Fayetteville Works’ site-wide PFAS air emissions even further beyond the significant reductions already achieved in recent years, despite an increase in production.”

The company’s significant reductions in air emissions were required by DEQ as part of the consent order.

As Hoppin reflected on the study results, she sounded dismayed. PFAS contamination in the Cape Fear River Basin appears to be worse than scientists had surmised in 2017, when the public became aware of GenX in the drinking water. “It’s unfortunate that eight years later we’re getting a broad picture of what’s been happening.”

Chemours has not announced a timeline for its expansion. DEQ is reviewing the company’s permit applications, and after the agency releases the draft permits, it will hold public hearings and a public comment period.

Two weeks after the study was published, on Nov. 6, Chemours announced its latest financial results to investors and the public. The company’s net sales of $1.5 billion were flat compared with the third quarter of the previous year. But one product showed an 80 percent year-over-year growth: Opteon, a refrigerant used at data centers. It emits TFA.

Upcoming in Forever War: Residents of the Lower Cape Fear River Basin are opposing a plan by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plans to deepen and widen parts of the Lower Cape Fear River at the Wilmington Port. The $1 billion project would stir up PFAS in sediment in the shipping channel—sediment that the Corps would need to dispose of—potentially harming the health of people and wildlife. PFAS and GenX are found in the Robeson County landfill, which accepts waste from Chemours.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,