The rise of AI data centers has sparked panic about how to provide enough electricity to support new development without overheating the planet and saddling everyone with unaffordable utility costs.

My advice: Let’s take a deep breath.

While the concern is justified, much of it is based on proposals with a low likelihood of coming to fruition.

Several reports issued over the past week help provide context on the implications of the AI boom.

“The sky isn’t falling,” said Louisa Eberle, a Pennsylvania-based senior associate for the Regulatory Assistance Project, a nonprofit organization that provides advice to utility regulators and lawmakers.

She is co-author of a report, “Building Resilient Foundations for Large Loads,” which can serve as a guide for state officials wondering how to manage the surge of proposals to build large data centers.

My main takeaway is that states already have processes to manage requests for large developments, and this framework is well-positioned to handle data center growth.

But some gaps exist and the report outlines how to address them.

First, states should ensure their economic development offices consult their utility regulators to confirm there is enough electricity to serve data centers before offering state incentives to attract development.

Second, states need to invest in forecasting to better assess how much electricity, water and other resources they will need to accommodate development. Better forecasting can help states determine which projects are likely to get built and which are not.

“There’s a range of data center developers in the game,” Eberle said. “There are sophisticated ones that have been around a long time. There are also a lot of newer folks that are more like real estate developers, that are just trying to get things set up with a connection to plug into power, and then they plan to sell that off to a hyperscaler.”

Hyperscalers are companies such as Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft that operate some of the largest data centers to support cloud computing and artificial intelligence.

The underlying problem: “Nobody knows exactly which of these projects for sure will or won’t go forward,” Eberle said.

But it’s safe to say that many of the proposals are unlikely to be built.

“In this industry, and in many things, there is a hype cycle,” said Camille Kadoch, a Wisconsin-based principal and general counsel for the Regulatory Assistance Project, and a co-author of the report.

I’ve seen my share of hype cycles in U.S. energy, from the rush to build ethanol plants in the early 2000s, to talk of a coal power renaissance in the late 2000s, to the seemingly perpetual speculation that nuclear power is primed for a comeback.

In each case, some projects were completed, many weren’t, and it took a few years to determine what the market had in store.

With data centers, there is no doubt that a construction boom is happening. What we don’t know is how long it will continue.

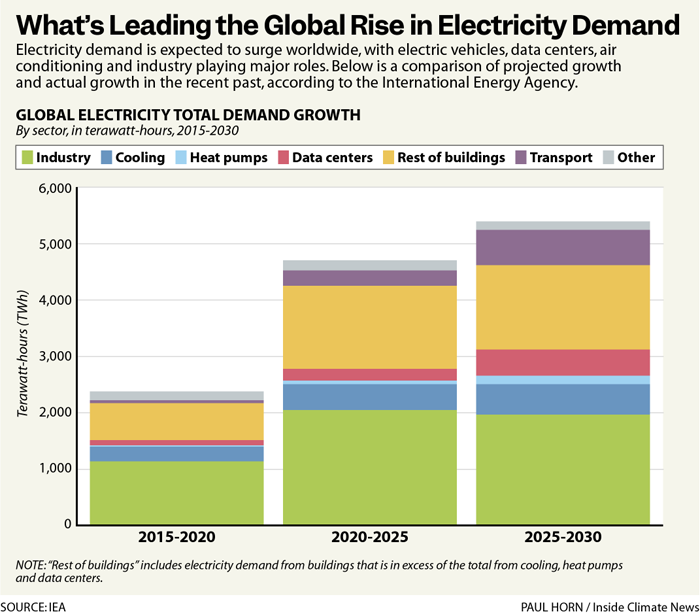

The International Energy Agency issued a report last week estimating that global electricity demand is poised to grow by an average of 3.6 percent per year for the rest of this decade. That may sound like a small number, but it’s a lot considering that much of the world had slow growth for the previous two decades.

The increase is due to the arrival of the “Age of Electricity,” according to IEA, with growing demand for power across sectors, including for data centers. Renewable energy is rapidly growing to meet this demand, and by 2030 about half of the world’s electricity will come from a combination of renewables and nuclear power, IEA said.

Factories are the leading source of global demand growth. IEA uses the term “industry” for this category, which the report says will account for 36.5 percent of the increase in electricity demand, as measured in terawatt-hours, between 2025 and 2030.

Data centers are way down on the list, accounting for 8.6 percent of the increase. I don’t want to minimize this. For a highly specialized type of business to account for nearly 9 percent of global growth in electricity demand is significant. But it’s less than the increases in other sectors, including from the global shift to electrified transportation, which is 11.5 percent.

The picture is different if we focus on the United States. Here, electricity demand is projected to grow at an annual average rate of about 2 percent between now and 2030, with about half of the increase attributable to data centers, the report said.

This indicates that the United States is moving faster than the rest of the world to build data centers and is slower to electrify other sectors.

I realize I advised you to take a deep breath and not panic over data centers, but it’s important that I also share some of the most troubling indicators.

Cleanview, a market intelligence firm that tracks renewable energy and data centers, issued a report analyzing plans for 46 U.S. data centers that have said they will generate their own electricity by building power plants on-site or nearby, rather than obtaining power from the grid.

Of the projects that specified their power plant technology, about three-quarters of the capacity is set to be met by natural gas power plants. This is despite many of the largest data center companies having corporate commitments to power their operations with renewable or carbon-free electricity.

“Nearly every project we reviewed mentions renewables, hydrogen, or nuclear in its public announcements,” said Michael Thomas, who leads Cleanview, in the report’s introduction. “But the equipment actually being installed in 2025 and 2026 is almost entirely gas-fired.”

Thomas writes that the 46 data centers have a combined power demand of 56 gigawatts, and represent about 30 percent of all planned data centers that he is tracking. (For perspective, the country had 292 gigawatts of combined-cycle natural gas plants operating as of November, which is the most common type of natural gas plant based on capacity.)

This heavy reliance on natural gas is likely to outpace any idea of a carbon budget and contribute to environmental pollution.

The report also delves into how the new gas plants are obtaining turbines to operate them despite a global shortage and years-long waiting lists for the most popular and efficient models. Companies are buying turbines from unconventional sources, including a business that manufactures them for use in cruise ships, the report said.

The larger point is that developers are doing just about anything to get data centers operational as quickly as possible.

I asked the Regulatory Assistance Project co-authors what they think of this growth in companies building their own gas plants to support data centers.

They said the scale of the planned construction raises questions about whether the turbines will be available on time and will operate as envisioned, and whether there is sufficient natural gas supply to meet such a large increase in demand.

Also, they said, regulators will need to closely monitor whether these data centers plan to use grid power as a backup when their on-site power plants are undergoing maintenance.

My recommendation, looking broadly at all data centers being proposed, is to be prepared for the likelihood that many or even most of these projects will not get built. It’s also clear that states need to get much better at assessing how much of this prospective demand is likely to materialize.

Other stories about the energy transition to take note of this week:

EPA Revokes the Endangerment Finding. So What Does This Mean? The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is expected to formally revoke a rule that is the legal basis for federal regulation of greenhouse gas pollution. ICN’s Marianne Lavelle explains the landmark rule and the potential implications of its cancellation.

Ford Reports a Big Loss, Says EVs Won’t Be Profitable for Three Years: Ford Motor reported a fourth quarter loss of $11.1 billion and an overall loss for 2025 of $8.2 billion, with much of the red ink attributable to electric vehicles, as Neal E. Boudette reports for The New York Times. The company said it expects EV losses to continue in the near term and hopes to reach a break-even point in 2029. Ford was a leader in developing EVs, but has struggled to turn a profit on these models, as consumer adoption has fallen short of expectations and recent U.S. policies have hurt demand.

Geothermal Heating Saves a Colorado College Money and Water: Colorado Mesa University has recently doubled in size but its energy usage is close to flat in part because the leaders decided to install an advanced geothermal heating and cooling system, as my colleague Phil McKenna reports.

Virginia Considers Bill to Make It Easier to Site Solar Projects: The Virginia House passed a measure last week that would prohibit local bans on building solar projects and also spell out requirements designed to address the concerns of local governments, as my colleague Charles Paullin reports. The bill responds to an increase in local rules that have made it difficult to build solar in much of the state.

Inside Clean Energy is ICN’s weekly bulletin of news and analysis about the energy transition. Send news tips and questions to [email protected].

Clarification: This story has been modified to clarify the author’s view that many or most proposed data centers will not get built, a statement in general about all data centers and not specifically about the ones in the Cleanview report.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,