Pathogens around the world just got a helping hand from the Trump administration.

Next year should have been a year of celebration for experts dedicated to ridding the world of disabling and deadly infectious diseases. It would have been the 20th anniversary of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Neglected Tropical Diseases Program, which has helped billions around the world recover from debilitating infections like hookworm, dengue fever and Chagas’ disease. Instead, the Trump administration eliminated the program in May.

The move came after President Trump withdrew the United States from the World Health Organization on his first day in office, and later canceled more than $530 million in grants for infectious disease research. Then in August, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. terminated nearly $500 million in grants to develop vaccines using messenger RNA, or mRNA, technology.

The Trump administration justified eliminating USAID neglected tropical disease (NTD) funding claiming that such programs “do not make Americans safer.” Yet many of these diseases already affect millions of Americans. Others are just a plane ride away.

The loss of U.S. funding for neglected tropical diseases, which followed the United Kingdom’s withdrawal of financing after Brexit, “will likely collapse global NTD control and elimination efforts,” infectious disease experts warned in Microbes and Infection in July.

“The same science and infrastructure that develops tools for global threats also strengthens U.S. preparedness,” said Kristie Mikus, executive director of the Global Health Technologies Coalition, which advances technologies for infectious diseases and poverty-related neglected tropical diseases.

The public understands this, she added. “Ninety percent of Americans say investing in research is important to preventing the next pandemic.”

The administration also released a report led by Kennedy on Tuesday focused on reversing “the childhood chronic disease crisis by confronting its root causes,” citing the American diet, absorption of toxic material and medical treatments among other potential drivers.

Yet the Make America Healthy Again report made no mention of climate change, even though the EPA warned in 2023 that climate-related stressors like extreme heat experienced during childhood can cause chronic disease and, as researchers found in a 2022 New England Journal of Medicine article, “nearly every child around the world is considered to be at risk from at least one climate hazard.” The MAHA report also ignored neglected tropical diseases, even though they disproportionately affect children, causing cognitive decline and disability.

Neither the White House nor HHS responded to questions about how they planned to keep Americans safe from diseases that already affect millions in pockets of poverty across the country without funding research or vaccine development.

NTDs include a diverse group of infections caused by various pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi, many transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, flies and other vectors. They infect more than a billion people around the world, according to WHO estimates.

The diseases, though common, persist in impoverished areas. They affect some of the world’s poorest people in communities that have historically lacked adequate infrastructure, sanitation, access to healthcare and, critically, the power to attract the attention and funding needed to treat and prevent the diseases.

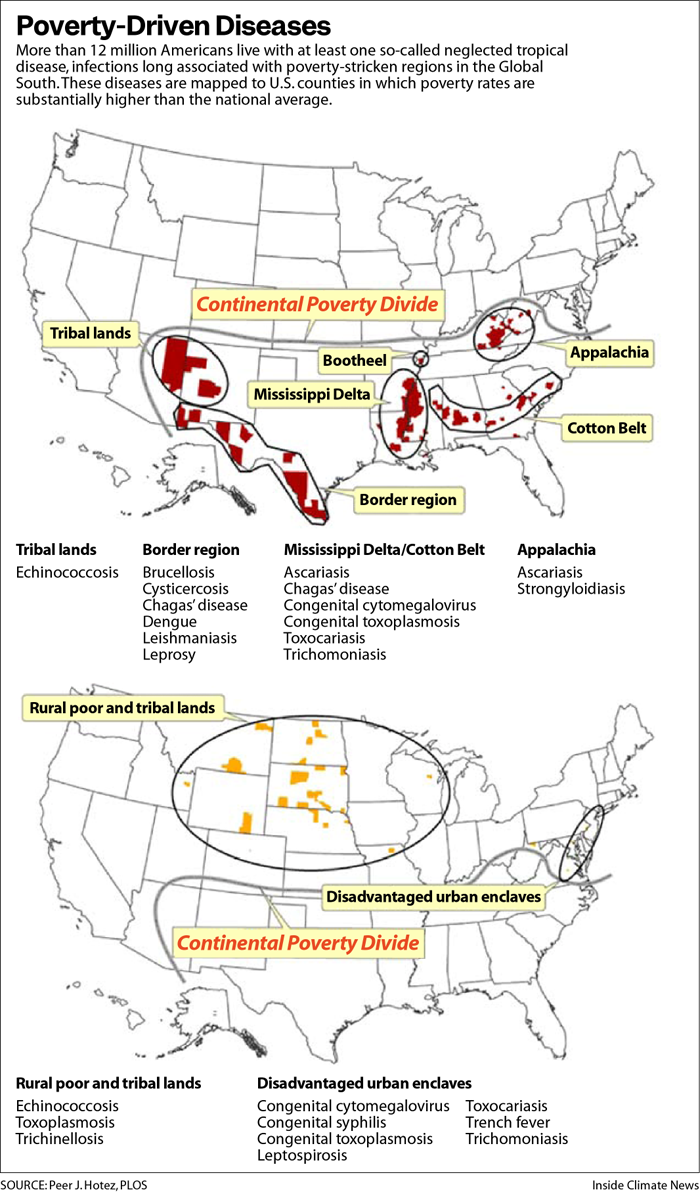

Yet, studies led by Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, found that most of these diseases affect people living in poverty in wealthy countries. At least 12 million Americans, which Hotez believes includes “a substantial percentage” of children, suffer from at least one neglected tropical disease.

Hotez calls the chronic, debilitating conditions “the most important diseases you’ve never heard of.”

Many Americans suffering from NTDs live in five states along the Gulf Coast: Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis recently announced his intention to end childhood vaccine mandates.

“The NTDs we are seeing here in South Texas and Gulf Coast are Chagas’ disease, soil-transmitted helminth infections such as hookworm and toxocariasis, mosquito-transmitted virus infections like dengue, tick-borne illness and now malaria is coming back,” said Hotez, who has helped develop vaccines for several NTDs, including hookworm and Chagas’ disease. “Similar phenomena are occurring in Southern Europe,” he added, citing climate change and urbanization as drivers.

David Hamer, professor of global health and medicine at the Boston University School of Public Health, said there is also “a substantial risk” that the U.S. could see the introduction and spread of at least two other diseases, chikungunya and Oropouche virus, due to climate change, greater distribution of their vectors and international travel.

A new study found that cases of dengue fever, a typically nonfatal infection transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, increased with rising temperatures between 1995 and 2014. But other factors may be more important to the spread of these types of diseases than temperature and climate, experts say.

“Climate change may increase disease risk, but even the modeling studies show risk can decrease in some places, too,” said Andrew Read, an expert on infectious disease dynamics and senior vice president for research at Pennsylvania State University.

The risk of outbreaks and pandemics is increasing due to population growth, more human movement aided by air transportation and habitat destruction, Read said.

“The USAID and mRNA cuts are a disaster for that reason,” Read said. “Global disease security is national disease security.”

Diseases of Poverty

On September 4, HHS Secretary Kennedy, who has long spread false claims about vaccines’ harms, testified before the Senate Finance Committee about the administration’s health care agenda. In one particularly heated exchange, Sen. Michael Bennet, a Colorado Democrat, asked Kennedy if he was aware that one of the people he named to the nation’s immunization practices committee wrote, “Evidence is mounting and indisputable that mRNA vaccines cause serious harm, including death, especially among young people.”

Kennedy said he wasn’t aware that his committee pick had said that, then added, “But I think I agree with it.”

There is no evidence to support the claim.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowTraditional vaccines provide protection against a disease by introducing a weakened, inactive whole or partial pathogen into the body to trigger an immune response. The mRNA vaccines, by contrast, introduce a molecule, mRNA, that tells cells to produce a protein from a pathogen to stimulate an immune response.

When the mRNA COVID vaccine rolled out in 2020, researchers had been working on the technology for decades.

Most of the publications in the “research collection” Kennedy cited to justify canceling mRNA vaccine research don’t actually focus on vaccines but detail the harms of COVID infection, experts who reviewed them found. At least one of those involved in compiling the articles has a long history of misrepresenting vaccine safety.

Duane Gubler, who headed vector-borne disease divisions at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for 25 years and now chairs the Global Dengue and Aedes-Transmitted Diseases Consortium, called the decision to terminate mRNA vaccine research “the biggest mistake that Trump has made yet.”

All vaccines, including mRNA vaccines, can have rare adverse events. But the real problem with the mRNA vaccines was health agencies’ failure to communicate what the vaccines did and didn’t do, said Gubler, who is also emeritus professor at the Duke University NUS Emerging Infectious Disease Program in Singapore. Experts knew early on that they prevented severe illness, hospitalization and death in vulnerable populations but didn’t stop infection, Gubler said. “And that was never communicated properly.”

Good public health is not a democratic process, he said. “The progress that we made with diseases like smallpox, with yellow fever, with measles, with polio, that was done through mandates,” he added.

“The dumbest thing I’ve ever heard is to get rid of those mandates for children.”

Unless Florida goes back to vaccine mandates, Read of Penn State said, it’s just a matter of time before children in Florida will be crippled from polio viruses. All it takes to restart transmission is for someone to bring poliovirus in from abroad.

Diseases like yellow fever, dengue and malaria were widespread in the U.S. until the middle of last century. Outbreaks were largely eliminated through a combination of disease surveillance, concerted public health campaigns to control mosquitoes and their habitat and, in the case of yellow fever, vaccination.

But controlling outbreaks of infectious diseases requires constant vigilance, experts say.

Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands declared outbreaks of dengue fever last year and several states have reported local dengue transmission, according to the CDC. Cases of locally transmitted Chagas’ disease have been identified in eight states, including California. In 2023, the first “home grown” U.S. cases of malaria in 20 years were reported in Texas, Maryland and Florida.

And now, the resurgence of yellow fever in Africa and South America has researchers worried about the potential of a global pandemic. A yellow fever pandemic in today’s world, the international team of scientists led by Gubler warned in April, “would cause a devastating public health crisis that, because of the much higher lethality, would make the COVID-19 pandemic pale by comparison.”

A yellow fever vaccine is available. But without expanding the global supply and ensuring high vaccination rates, outbreaks are likely to continue and spread to new regions.

The Trump administration’s budget includes no provision to contribute to those efforts.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,