SALEM, Mass.—Paul Wright leans over a 17th-century granite barrier and points at a faint watermark depicting Salem Harbor’s daily rise and fall.

“On a normal day, high tides reach just four feet from the top of the seawall,” he says. “When there’s a big storm or king tide, that’s when it gets close to spilling over.”

That seawall is the first line of defense for one of America’s most storied homes, protecting it from centuries of battering New England storms. The colonial manse, the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion, is now best known as the setting for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The House of the Seven Gables.”

Sixty years after the novel was published in 1851, the structure fell into disrepair until Caroline Emmerton, a philanthropist, restored it in the early 1900s as both a museum and immigrant settlement house.

By 1924, she had moved three colonial buildings onto the grounds, intent on preserving Salem’s past. Strolling the property perched just above the harbor, Emmerton might have wondered if her legacy would endure. Would future generations care for Salem’s past? Would the buildings she saved remain monuments, or fade into memory?

What she likely never could have foreseen was that the greatest threat to her legacy would not come from neglect, but a changing climate.

The encroachment of a warming sea and global warming-fueled storms are no longer distant threats—they are already reshaping Salem’s waterfront. At the House of the Seven Gables, rising tides and creeping groundwater threaten to undo centuries of preservation work. Now, the same museum staff who care for Hawthorne’s literary landmark and Emmerton’s legacy are facing a new test: how to save history from the sea.

Wright is the director of preservation and maintenance at the House of the Seven Gables Settlement Association, known as The Gables, the nonprofit behind the historic property. He joined the staff in 2022, eager to launch decarbonization projects: tightening insulation, boosting energy efficiency and adding on-site renewables. But as climate impacts grew harder to ignore, resilience overtook efficiency as the more urgent demand.

Today, six historic structures stand on the site. Three of them are classified as First Period homes, built between 1625 and 1725, a rare architectural feat since only 350 First Period houses remain intact across the country.

Each building, along with the property’s seawall, has endured generations of storms. Yet in a warming world, their limits are becoming painfully clear.

In 2019, a visitor suddenly sank knee-deep into the lawn. A small sinkhole had opened near the seawall. Only later did staff learn that salt water, seeping through during high tides, had been carrying away sediment, hollowing out the ground until it gave way.

“That was the first wake-up call,” said Susan Baker, Curator of Collections of The Gables.

The second came in the form of a mold bloom. After a heavy rain in 2023, water seeped into the basement of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1790 birthplace, relocated to the property in 1958. Unaware of the flooding, staff later discovered mold creeping across the basement, damaging furniture and books tied to Hawthorne’s life.

Soon after these events, The Gables staff began shoring up defenses. High-end dehumidifiers and sump pumps were added when funds allowed. Wright fitted larger gutters onto the steep medieval-style roofs and regraded slopes, hoping to chase water away from the foundations. But as emissions continue unabated, meaning that climate impacts in the Northeast are expected to worsen, it became clear these remedies were only buying time.

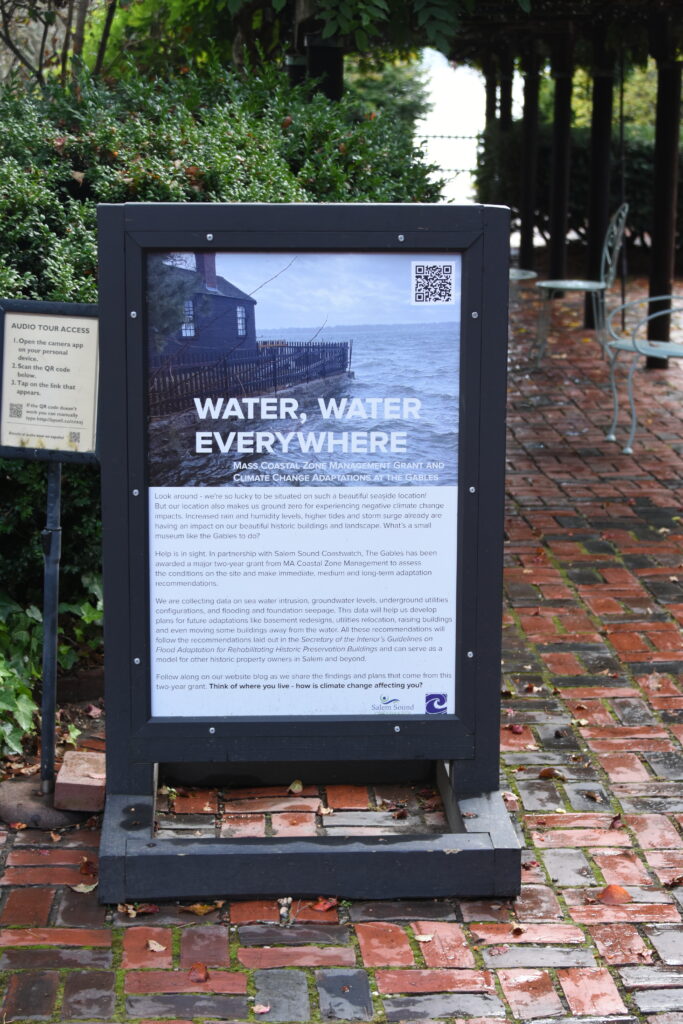

In 2022, the organization secured a grant from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs to study the property’s vulnerabilities and chart a long-term preservation plan.

With help from architects, engineers and Salem Sound experts, the team dug groundwater monitoring wells and conducted in-depth flood projections to better understand the properties’ current and future vulnerabilities.

“The belief before research began was, we raise the seawall and we’ll be fine,” said Wright. But as research unfolded, the evidence pointed to a harsher reality—one no historic property owner wants to face.

Flooding, Mold and Pests

The Counting House, a small 1830s shack once used by merchants for business and now serving as a children’s education center, sits at the harbor’s edge. It lies within the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s VE—velocity and elevation—flood zone, the designation reserved for the most vulnerable coastlines.

Wright watched as a Nor’easter barreled into Salem on a cold January day last year. It was his day off, but he came anyway—ready to move artifacts, shield equipment or throw up barriers if the sea broke through. Waves lapped over the stone wall outside the Counting House, and for a moment he feared this would be the storm that finally overwhelmed the property.

But the storm struck a few hours before high tide, pushing the worst of the surge north of Salem. The Gables was spared. A near miss, Wright thought.

“We’ve been really lucky that a once-in-a-hundred-year storm hasn’t hit yet,” Wright said, knocking on a 17th-century wood beam to ward off the specter of that happening. The staff is superstitious—an almost unavoidable trait in Salem. “A hurricane or Nor’easter that hits during high tide would be devastating.”

For now, most of the site sits outside FEMA floodplains. Projections show that reprieve won’t last. According to Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management, by 2050 three of the historic structures—the House of the Seven Gables, the Counting House and the Hooper-Hathaway House of 1682—are expected to flood once a year. By 2070, every structure except the Phippen House, a 1792 home now used as offices, will likely face annual or biannual flooding.

These models are based on probabilities and don’t account for the site’s hydrological defenses, according to Wright. Still, they indicate the entire southern half of the property could soon fall within FEMA’s highest-risk flood zone.

And water is rising from below as well as from the sea. On Salem’s coast, groundwater is tidal; as sea levels rise, so does the water table. Today, high groundwater sits about four feet above sea level—reaching the base of the visitor center basement and reaching within inches of the foundations of each First Period home. By 2070, high groundwater could climb to 10 feet.

“At that point water will start coming up in bulk, introducing more humidity and even filling up the basements,” said Wright.

Moisture from above and below is already exacting a quiet toll. Mold blooms are now largely contained by dehumidifying efforts, leaving only minor impacts, but the region’s warming, humid climate has opened the door to new threats.

Baker remembers one moment vividly. While re-designing the House of the Seven Gables’ master bedroom in 2016, she and a colleague began peeling back the bed set. To their dismay, small holes appeared in the fabric: webbing clothes moths had slowly chewed through the 18th-century-style hangings draped around the bed—the most expensive item in the home at the time.

New England museums have largely escaped the insect infestations that plague collections in hotter, more humid parts of the country, according to Susan Pranger, adjunct professor at Boston Architectural College and author of a book on historic materials in a changing climate.

But beginning in the early 2000s, curators started finding webbing clothes moths, carpet beetles and other pests that devour animal-based fibers like wool, silk and leather, she said. Left unchecked, they can hollow out textiles or reduce rare artifacts to dust.

Each historic home on The Gables site is now deep-cleaned every two weeks to make sure not even a hair fallen from the head of an unsuspecting tourist is left for pests to feed on. “It’s a constant battle,” said Baker.

For years, The Gables stewards hoped a higher, sturdier seawall would solve their hydrological challenges. But the defenses along the harbor are a patchwork of public and private seawalls—each built at different times, with different materials, and stand at uneven heights.

“If we were to raise our wall it would affect our neighbors,” Wright said. “Some of their seawalls are shorter, so water would be pushed onto their property and in all likelihood find its way back to ours.”

Without a coordinated citywide effort, any seawall upgrade would do little to protect the pieces of Salem’s history found on the property.

Confronted with dire projections and dwindling faith in municipal action, The Gables staff reached a sobering conclusion: the historic structures would have to retreat from the coast.

The Final Move

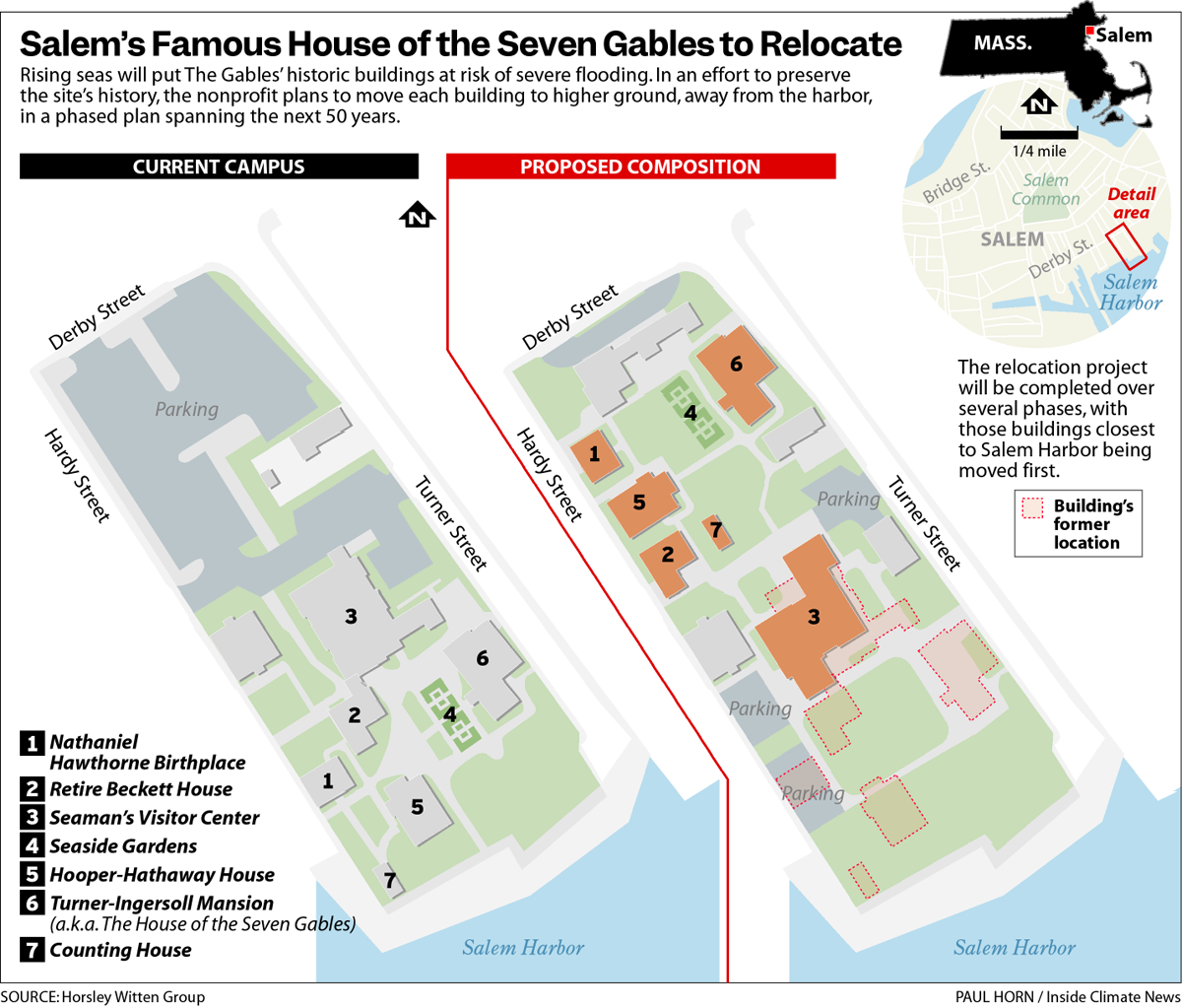

In May, The Gables released a 50-year adaptation plan with funds from its Massachusetts state grant.

“The only way this is going to work is with state or federal funding,” Baker said. The estimated 45-year project will cost millions of dollars.

At its core, the plan details the relocation of five historic structures about 100 yards inland, onto what is now the property’s parking lot. Had that space not been available, the process would have been far more complicated—requiring the purchase of new land and the possibility of moving the homes miles away, Wright said.

“A structure being in its original location and form is vital for authenticity, but we are going to have to rethink how we value that, ” said Pranger. “If we don’t move pieces of history now, then we’re just going to lose them forever.”

For Wright, retreat isn’t merely a compromise between accuracy and survival—it’s an opportunity. “We didn’t want to just raise the buildings because then they would just look like a bunch of old coastal shacks rather than a colonial revival property,” Wright said. Instead, by shifting the homes inland toward the street, the plan will help restore the historic feel of a neighborhood that draws millions of visitors each year to experience its maritime lore and the legacy of its witch trials.

The adaptation extends beyond relocation to historical reconstruction. Along the seawall, staff envision a dual-purpose garden where native plants will anchor the soil and soak up seawater seeping through the wall. Threaded through the landscape will be a walkway honoring the Naumkeag people, who fished along Salem’s shores for centuries before colonization.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe timeline is daunting. The first building to move will be the Counting House, by 2030, followed by the Hooper-Hathaway House, Retire Beckett House and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s birthplace. Each step will be expensive and painstaking.

And then there is the House of the Seven Gables, a house that has passed from wealthy colonial merchants to immigrant families, entered the pages of a classic American tale and today opens its doors to hundreds of thousands of curious visitors each year. Of all the historic buildings on site, it is the only one still resting on its original foundation.

“It’s a one of a kind First-Period mansion foundation,” Wright said, descending worn wooden stairs. The air in the fieldstone basement is cool and dry, scrubbed of its usual dampness by two industrial dehumidifiers that fill the cellar with a low hum. The dehumidifiers protect an architectural jewel: a brick-arched chimney base from the 1670s—possibly the oldest of its kind in the country, Wright said with a trace of pride.

For now, the staff hopes that waterproofing measures will keep flooding at bay long enough for the house to remain in place until 2070, but its connection to the original foundation makes it both irreplaceable and invaluable.

When rising tides and creeping groundwater finally overtake the home, the staff plans to leave the foundation where it lies. Exposed for visitors to see, it will remain in the earth: a fragment of colonial history, an echo of Emmerton’s legacy and a solemn marker of the moment when climate change forced a home that withstood three centuries of life to retreat.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,