Thousands of gallons of oil and toxic wastewater poured out of a pipe running through a Monterey County oil field on Friday, Dec. 5, in the latest of several recent spills around the state. The pipe released 168 gallons of oil and nearly 4,000 gallons of toxic wastewater from drilling operations managed by Aera Energy at the San Ardo Oil Field, which sits near olive groves, row crops and ranches at the southern end of the county’s $5 billion agricultural region.

For environmental justice communities and their allies, it’s yet another sign that California is failing to live up to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s claims of being a global climate leader.

Over the past three months, California has averaged more than 70 oil spills per month, with petroleum polluting ports, harbors, streams and oil field soils, state data shows. In the past month alone, oil has poured out of malfunctioning pipes and tanks into ditches and dirt roads in Kern County, onto the shoulder of a highway in Tulare County, into a seasonally dry creek bed that feeds Los Angeles County’s Santa Clara River and into another creek that ultimately flows into the Santa Clara, known as the only wild river in Southern California.

The day before a pipe failed at the San Ardo oil field last week—the 95th spill in that oil field over the past 20 years, according to state data—a drilling rig off the coast of Santa Barbara County dumped crude oil into the Pacific Ocean.

The San Ardo incident is just the latest in a string of spills happening all around the state, said Hollin Kretzmann, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute. “California is supposed to be a leader in moving us towards a fossil fuel-free future, but these kinds of spills are a stark reminder that the state has a lot of work to do to live up to that,” he said.

The San Ardo Oil Field is one of the most climate-polluting, carbon-intensive fields in the world. Carbon intensity, a measure of total greenhouse gases emitted from exploration and drilling through transport to the refinery, increases with the amount of energy used to extract the oil.

The energy required to keep old oil fields in production can increase dramatically, along with climate pollution, even as petroleum yields drop, research shows. California’s oil production has plummeted since the mid-1980s, as it has relied more and more on energy-intensive methods like steam injection to wrest thick, tarry crude oil from depleted, hard-to-reach underground reservoirs.

San Ardo’s carbon intensity is about twice as high as the average for crude oil destined for California refineries.

The failed pipe in the aging oil field released toxic petroleum-tainted fluids about a mile away from the Salinas River, an irrigation source for farmers in Monterey County’s Salinas Valley, known as the “Salad Bowl of the World” for its year-round production of fruits, lettuce and other vegetables. The spill started a little after 7 a.m., when farmworkers around San Ardo are typically already out in the fields, planting carrots and wrapping up the cauliflower harvest.

Many oil fields operate near agricultural fields, compounding health risks for nearby communities. Around San Ardo, growers sprayed tens of thousands of pounds of pesticides classified as either possible, probable or likely human carcinogens and hundreds of pounds of chemicals linked to Parkinson’s, state records show.

“We need more long-term solutions to stop dangerous oil spills from happening in our communities,” said state Sen. Lena Gonzalez, a Long Beach Democrat who authored legislation to restrict neighborhood drilling.

“Over the years, we’ve made progress, but there’s a lot more to do,” Gonzalez said. “Today’s growing uncertainty under the current federal administration, on everything from climate to the economy, underscores just how urgent that work is.”

A spokesperson for California Resources Corp., which became the state’s largest oil producer after acquiring Aera last year, said employees immediately responded to the incident and that the cleanup was swift. “All contaminated soil was removed within about 72 hours,” the spokesperson said.

“A Non-Oil Future”

Last month, Gov. Gavin Newsom returned from COP30, the global climate talks in Brazil, after forging partnerships with several countries to reduce methane emissions and build climate resilience. The governor’s actions at the summit, his administration said, forged “new global partnerships and historic progress that cements California as a driving force for climate action worldwide.”

Yet the Newsom administration’s efforts on the global stage have left California climate and environmental justice activists perplexed by his recent actions at home.

“Last fall, it was hugely unfortunate that the governor rammed through Senate Bill 237, which fast-tracks oil and gas drilling in Kern County with no further environmental review,” said Kretzmann.

Oil and gas companies and their trade groups spent more than $26 million between January and September of this year to influence state lawmakers on numerous issues and bills, including S.B. 237, state records show.

After Newsom signed the bill in September, Western States Petroleum Assn., a powerful oil and gas lobbying group, credited the governor’s leadership for increasing crude production in Kern County “under the most stringent regulatory framework in the country” to ensure access to affordable fuels.

The law aimed to lower gas prices by codifying an ordinance to streamline oil and gas drilling permits adopted by Kern County, the state’s oil epicenter. The county had recently revised the ordinance after years of legal challenges and a court ruling that it failed to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, a foundational tool for communities to participate in the environmental review of new projects.

The law greenlights potentially thousands of wells in the county that has probably suffered the most from oil and gas production, Kretzmann said. “At exactly the moment when we need to be doubling down on our transition away from oil production and towards electrification and a healthier and sustainable future,” he said, “the governor is hell bent on doubling down on onshore production.”

A coalition of climate, environmental justice and public interest groups had urged the governor and legislative leaders in August to amend a draft version of S.B. 237, arguing in a letter that the proposed actions marked “the arrival of the Trump Administration’s ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda in California” without affecting oil supply or gas prices as intended.

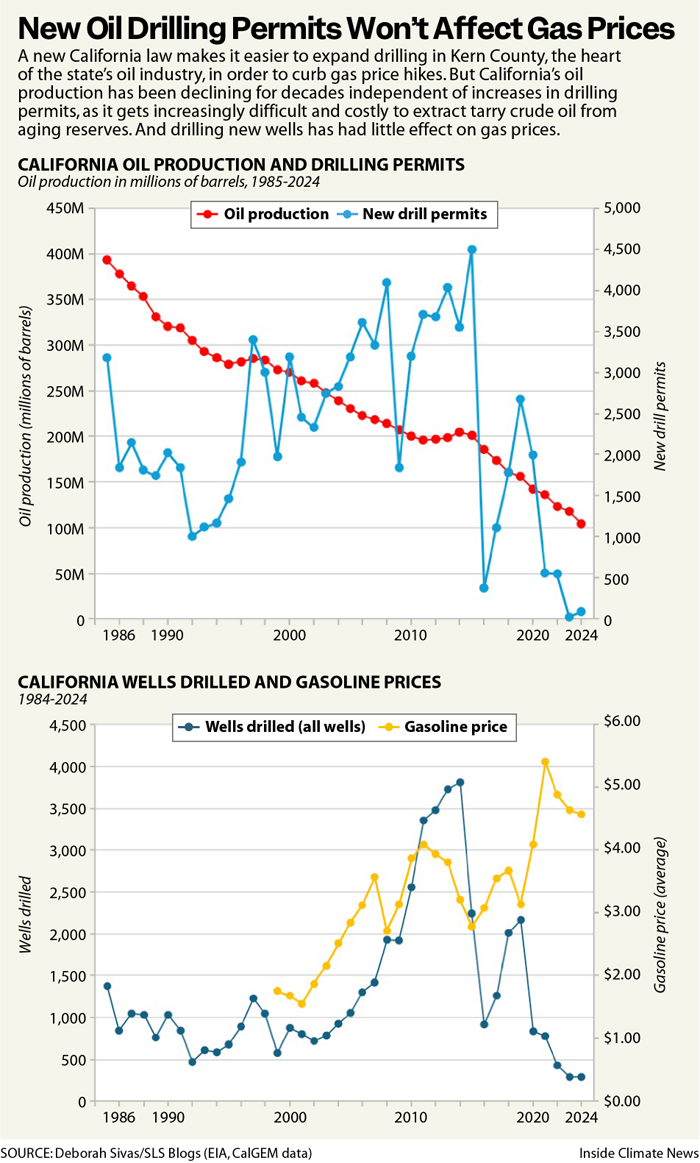

Gas prices are unrelated to what’s going on with oil and gas refining and production in California, which is a function of economics and geology, said Deborah Sivas, professor of environmental law and a co-director of Stanford University’s Environmental Law Clinic.

With increased adoption of EVs and progress on fuel efficiencies, “the long-term trajectory is less and less and less demand for gasoline,” Sivas said. Plus, California imports more than 70 percent of its crude, because it’s so expensive to get oil out of the ground in the state’s depleted oil fields.

When refineries in California announced impending closures this year, Sivas said, industry interests used the threat of $8 a gallon gasoline to “panic the politicians” into approving S.B. 237’s permit exemptions.

Fast-tracking oil drilling won’t affect pump prices, though, she said. In an analysis of decades of data on permit approvals compared to new wells drilled, Sivas found that new permits failed to increase gas production and that drilling new wells had no effect on gas prices.

“We absolutely should not be doing any new oil and gas infrastructure,” Sivas said. “We should be thinking about a non-oil future, and that means no more drilling and starting to really repurpose those refinery sites.”

The governor’s office did not respond to questions about why it promoted legislation that would allow more drilling, despite the lack of evidence that increased drilling will lower gas prices and while claiming to drive global action on climate.

Egregious Exemptions

Emma Silber was disappointed to see California pass S.B. 237. “Increasing drilling is not the answer here, and increasing drilling in already overburdened communities is very much not the solution,” said Silber, who signed the August letter as the climate justice program coordinator for Physicians for Social Responsibility LA.

“Once again frontline BIPOC communities, whether in neighborhoods or folks working in agriculture, are being sacrificed for the profits of the industry and political expediency,” she said.

Recent research found that air pollution from fossil fuels causes tens of thousands of premature deaths per year across the country, Silber said. “And if you’re looking specifically in California, there are over 10,000 early deaths due to the fine particles from oil and gas emissions.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowTexas and California bear the greatest burden for nearly all pollution-related health risks, including premature death, cancer and asthma, across the oil and gas life cycle, scientists reported in the study Silber referenced, published in Science Advances. But the study just looked at adult health outcomes, she said, and didn’t account for known reproductive harms, including increased risks of preterm births, miscarriages, early infant death and childhood cancer.

“We’re really concerned that as these drilling permits start to come out of Kern County, they’ll just be rubber-stamped and move forward really quickly,” Silber said. “And the impacts to Kern County are potentially really harmful.”

Cesar Aguirre has been documenting the health harms of Kern County oil and gas production for several years. In late September, Aguirre, who directs Central California Environmental Justice Network’s air and climate justice team, inspected a site around Lost Hills, a small, predominantly Latino farmworker community in western Kern County.

He saw two steam-injection wells with “a lot of fluid coming out” creating large puddles. The next month, operators in Kern County reported about half a dozen petroleum spills to California regulators. “That only happens whenever folks are actually out there and looking at these wells that are allowed to fall into this condition because of the egregious and gigantic exemptions that exist within California law when it comes to regulating oil and gas wells,” Aguirre said.

California exempts “heavy oil” development infrastructure and small producers from critical emissions control and leak detection and repair requirements, Aguirre said. “Sixty-eight percent of the oil that’s produced in California is heavy oil and 84 percent of the infrastructure associated with oil production is associated with heavy oil production.”

California likes to position itself as an environmental leader, Aguirre said, but where he lives in Kern County the state is a leader when it comes to leaks.

“I live in a California that has vast exemptions that allow leaks to happen legally in places like parks and places like parking lots next to apartment buildings and behind houses,” he said. “I live in a California that’s been corrupted by oil and gas politics, and the consequence of that is that I live in the dirtiest air basin in the entire United States.”

The fact that California politicians are allowing oil companies to drill thousands and thousands of new wells, Aguirre said, left him wondering if they’re aware of what’s happening and don’t care or if they need to be educated on what the reality of the on-the-ground conditions in California are really like.

Kern County is a beautiful place with a lot worth protecting, Aguirre said, adding that while it leads the state in oil production, it’s also a clean energy leader.

“It’s in the best interest of California for Kern County to diversify its economy as much as possible and step into being the energy leader that the next generation needs,” Aguirre said. “And I think that’s with renewable energy.”

County planners recently credited the region’s “vast solar and wind potential” as supporting an emerging energy hub.

“I would love for us to take that baton,” Aguirre said, “instead of trying to prop up an industry that cannot be properly regulated without completely undoing and redoing the system.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,