For the first time, global governments have agreed to widespread international trade bans and restrictions for sharks and rays being driven to extinction.

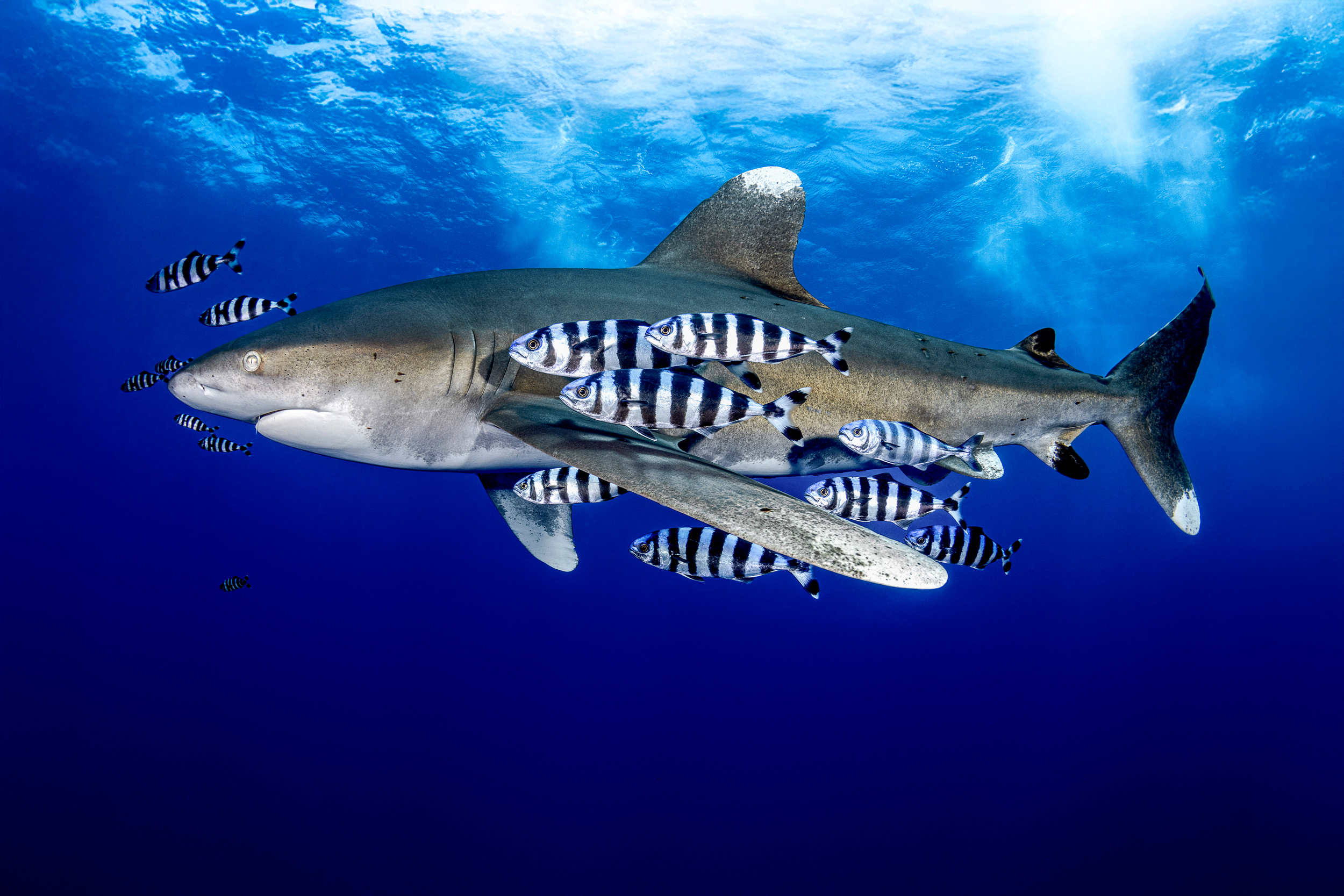

Last week, more than 70 shark and ray species, including oceanic whitetip sharks, whale sharks and manta rays, received new safeguards under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. The convention, known as CITES, is a United Nations treaty that requires countries to regulate or prohibit international trade in species whose survival is threatened.

Sharks and rays are closely related species that play similar roles as apex predators in the ocean, helping to maintain healthy marine ecosystems. They have been caught and traded for decades, contributing to a global market worth nearly $1 billion annually, according to Luke Warwick, director of shark and ray conservation at Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), an international nonprofit dedicated to preserving animals and their habitats.

The sweeping conservation measures were adopted as the treaty’s 20th Conference of the Parties (COP20) concluded in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, signaling a landmark global commitment to stop or regulate the demand for shark meat, fins, and other products derived from the animals.

“These new protections are a powerful step toward ensuring these species have a real chance at recovery,” said Diego Cardeñosa, an assistant professor at Florida International University and lead scientist at the school’s Predator Ecology and Conservation Lab, which is developing new technologies to combat the illegal trade of sharks.

More than a third of shark and ray species are now threatened with extinction. Pelagic shark populations that live in the open ocean have declined by more than 70 percent over the last 50 years. Reef sharks have all but vanished from one in five coral reefs worldwide. “We’re in the middle of an extinction crisis for the species and it’s kind of a silent crisis,” said Warwick. “It’s only in the last decade or so we’ve really, really started to notice that this is happening, and the major driver of it is actually overfishing.”

Unlike tuna and other commercially valuable fish that have been tightly regulated for decades, sharks have long lacked comparable controls on their trade and have often been treated as if they were another fast-reproducing seafood commodity.

“People treat sharks and rays, or have done over the last 50 years, as if they’re like other fish,” Warwick said. But unlike many fish that produce millions of eggs a year, sharks and rays take much longer to mature and produce significantly fewer young. Manta rays, for instance, may only give birth to seven live pups in their lifetime. “But we’ve been catching and killing them, just like other fish, and that, sadly, has led to these catastrophic declines.”

Manta rays are targeted primarily for their large gill plates, which are used in some traditional medicines in Asia aimed at detoxifying the body and boosting immunity, though there is no scientific evidence to support these claims. Their meat is sometimes turned into animal feed or consumed locally.

Shark fins remain a delicacy in luxury Chinese cuisine, prized in expensive dishes like shark fin soup. Shark meat is increasingly sold as a low-cost source of protein. It’s also a common ingredient in cat and dog food.

The livers of deep-water species like gulper sharks are also harvested for their oil, which is used to produce squalene, a staple component of topical skincare products and makeup. Years of unregulated trade of the species have driven population declines of more than 80 percent in some regions.

“The cosmetic industry, really, in a way, is driving the trade of the sharks,” said Gabriel Vianna, a shark researcher from the Charles Darwin Foundation, an international nonprofit dedicated to conserving the Galapagos Islands. In recent years, squalene has also been increasingly used in pharmaceuticals and even Covid-19 vaccines. “We should be using synthetic options and not exploiting these species,” Vianna said.

But until last week, there were no international controls in place to regulate trade in these species despite growing demand for their livers.

That has now changed through the latest decisions adopted at CITES, which Warwick said mark a turning point in marine conservation.

For much of its 50-year history, the convention focused on protecting iconic land species like elephants, rhinos, primates and parrots, or charismatic marine species like sea turtles, Warwick said. By 1981, CITES had imposed an international ban on all international trade of sea turtles, which Warwick credited for helping some species make remarkable comebacks in the last few decades. Only in the last 10 years, Warwick said, has the convention slowly begun recognizing sharks and rays with similar urgency.

This year at COP20, all proposed protections for sharks and rays were adopted, largely with unanimous support from CITES’ 185 member countries and the European Union, which Warwick said had never happened before.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe European Union is one of the top suppliers of shark meat to Southeast and East Asian markets, with its imports and exports adding up to more than 20 percent of global shark meat trade, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

Gulper sharks, targeted for their livers, as well as smoothhound and tope sharks, which are primarily fished for their meat, were listed under CITES’ Appendix II. Each listing covers multiple species—20 species of gulper sharks and 30 species of smoothhounds—grouped together because their products cannot be reliably distinguished in trade.

The listing requires all CITES parties to strictly regulate international trade of the species and demonstrate if it is traceable and biologically sustainable. Some species, including wedgefish and giant guitarfish—large shark-like rays targeted for their highly valuable fins—are now protected by a temporary suspension of trade.

Others, such as oceanic whitetips, whale sharks, manta and devil rays, can no longer be traded internationally at all. Under the new protections, CITES now lists them as Appendix I species, meaning they face a real extinction risk due to trade and are afforded the treaty’s highest level of protection.

“If you find an oceanic whitetip fin being traded, 90 days from here onwards, that’s an illegal product,” he said.

For many shark advocates, the new listings are bittersweet.

“We are very happy but we are very sad at the same time,” said Vianna. “We shouldn’t be happy about this species being listed. We should actually be really worried that there’s such a problem with them.” Meaningful implementation of the new protections will be critical to the survival of many of these species, he said.

Research published in November by Cardeñosa and Warwick found that fins from several shark and ray species, such as oceanic white tip sharks, which were previously listed under Appendix II, were frequently found in Hong Kong—the world’s largest shark fin market—between 2015 and 2021. Appendix II allows for regulated trade, but little to no legal trade in species like the oceanic white tip has been reported since CITES began regulating it in 2014, revealing a significant gap in the amount of sharks being traded and what is being legally documented. For example, genetic analysis of shark fins in Hong Kong detected more than 70 times the number of oceanic whitetip shark fins reported in official CITES records, indicating that more than 90 percent of the trade is illegal.

“This tells us that enforcement gaps remain, especially in large, complex supply chains,” Cardeñosa said in an email.

Now that the oceanic whitetip shark has been uplisted to Appendix I, which prohibits any international trade, Cardeñosa hopes loopholes that previously allowed the protected species and others to slip through will be closed.

“The new listings will not eliminate illegal trade overnight, but they will significantly strengthen the ability of countries to inspect, detect and prosecute illegal shipments,” Cardeñosa said. “Parties must invest in identification tools, capacity building and routine monitoring if these protections are to translate into real reductions in illegal trade.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,