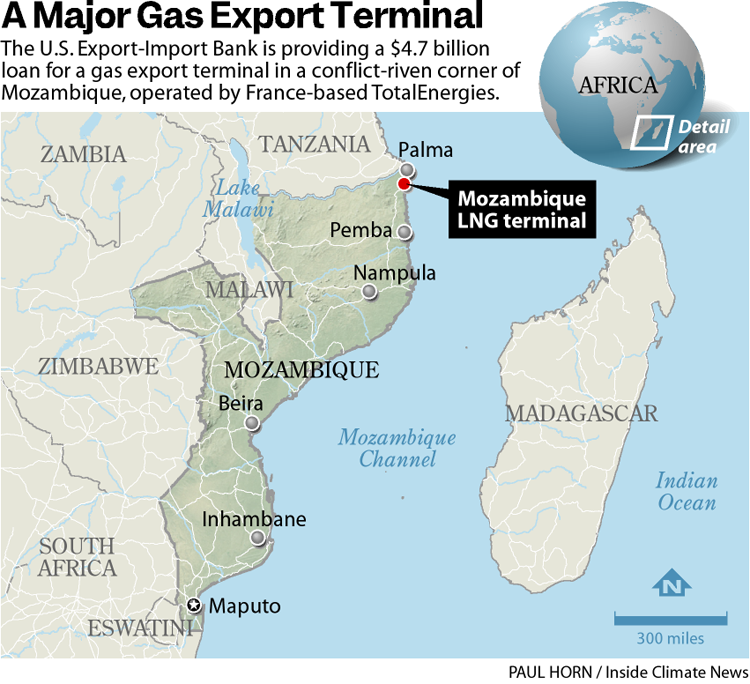

In the conflict-riven northern corner of Mozambique, a huge gas export terminal is moving ahead with the backing of the United States government.

Mozambique LNG would be one of the largest fossil fuel projects in Africa, with the capacity to export up to 43 million metric tons of liquefied natural gas per year at full capacity. The U.S. Export-Import Bank initially approved a $4.7 billion loan for the project in 2019, during the first Trump administration, when the development was led by Texas-based Anadarko Petroleum.

Since then, however, Anadarko sold its stake to France-based TotalEnergies, an Islamist insurgency forced a four-year halt to construction and security forces were accused of committing war crimes against civilians. The United States also became the world’s leading LNG exporter, setting up Mozambique LNG as a potential competitor to American projects.

Despite those changes, the Export-Import Bank last year approved an amendment to the loan allowing TotalEnergies to proceed without any new analysis on the impacts to jobs, the U.S. economy or human rights and the environment. The move drew sharp rebukes from human rights groups, environmentalists and even some conservatives, who argue the money would be better spent supporting domestic energy production.

“It doesn’t make any sense as to why the U.S. government, using U.S. taxpayer money, is funding a French company in Mozambique,” said Andrew Bogrand, a senior policy advisor for natural resource justice at Oxfam America, a nonprofit that fights inequality.

Bogrand traveled to the region last year and spoke with locals who reported continued insurgent attacks and kidnappings. He said the project would worsen climate change by unlocking a large gas field and is contributing to the region’s instability. The conflict has killed at least 6,400 people since 2017, including at least 20 over the last month, according to Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

“This is end-of-the-line extractivism,” Bogrand said.

In December, British and Dutch export credit agencies withdrew more than $2 billion in support for the project after a human rights group accused TotalEnergies of being complicit in the atrocities allegedly committed by government forces.

Despite the setback, TotalEnergies announced last month that construction was finally restarting, with the U.S. credit agency’s loan the largest single source of financing, according to data compiled by the Energy Policy Research Foundation.

The Export-Import Bank declined to comment and did not reply to questions for this article. In a press release announcing the loan amendment last year, it said the project would support 16,400 American jobs across 14 states at businesses that would supply equipment and services to Mozambique LNG. It said the project would not adversely affect U.S. LNG exporters, and that the loan would help counter the Chinese and Russian governments, which it said would have supported the project if the U.S. government did not.

Yet all those figures and assertions appear to rest on analysis done in 2019, when American LNG exports were one-third of what they were last year, an American oil company was leading the project and before rising insurgent attacks killed workers and forced TotalEnergies to halt work.

The jobs figure appears to include an undisclosed number of positions at Anadarko, which is now part of Occidental Petroleum and no longer involved, according to an agency document obtained through a public records request and shared with Inside Climate News. By the time the loan was finalized in 2019, Anadarko’s sale was already expected and the Export-Import Bank, also known as EXIM, said, “the U.S. content requirement of the contract supported by EXIM will continue to apply, and the related EXIM-supported goods and services to the project will be provided by the United States.”

Still, it is unclear whether the jobs attributed to Anadarko are now expected to go to another U.S. company.

The lack of any new analysis means the bank no longer knows what the project’s impact on the U.S. economy would be, said Lindsay Bailey, a staff attorney at EarthRights International, a nonprofit law firm representing Friends of the Earth in a lawsuit challenging the loan’s approval. The failure to conduct a new analysis, Bailey said, “violated EXIM’s governing statute and is inconsistent with EXIM’s mission to support American jobs.”

U.S. Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska) and The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board both criticized the loan for subsidizing a foreign project that would compete with domestic energy companies.

U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) said the bank did not alert Congress in advance of its 2025 decision to finalize the loan, depriving lawmakers of the opportunity to review and comment ahead of the approval.

“In its haste, EXIM has failed to notify Congress of its intent to sell out public health and our environment to line the pockets of ultra-wealthy corporate polluters,” Merkley said in a statement to Inside Climate News. “By approving billions of dollars for this dirty energy LNG project in Mozambique, EXIM is making sure we fail to address climate chaos, the biggest challenge humanity faces.”

Government officials in Mozambique say the project will generate revenue and promote economic development in the country. TotalEnergies says it will provide 7,000 jobs to Mozambicans and billions of dollars in contracts to domestic companies.

Some critics of the project say few benefits have materialized.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowRomão Xavier, an international development consultant in Mozambique and former country head for Oxfam, said some locals are hopeful the development could provide jobs, but that many fisherfolk were displaced to make way for the gas project. While TotalEnergies has provided them with new housing and transit to fishing grounds, Xavier said, the schedule of that transportation hasn’t necessarily coincided with when people need to be on the water.

“The project has little benefit as of today,” Xavier said.

In 2024, a Politico investigation detailed how a Mozambican military unit had detained, tortured and killed dozens of villagers who had been fleeing the fighting near the LNG project. Subsequent research by others has supported that report, and in November, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights filed a criminal complaint with French prosecutors against TotalEnergies, accusing it of complicity in war crimes by financing and supporting the military unit. The complaint cited internal company documents that it said showed TotalEnergies was aware of violence committed by the military against civilians.

TotalEnergies did not respond to questions for this article but issued a statement after the complaint was filed, saying it “firmly rejects” all the accusations against the company. It added that it “strongly and categorically rejects Politico’s allegation that Mozambique LNG or the Company had, or could have had, any knowledge of the acts of violence reported in the Politico article and underpinning the complaint.”

In addition to TotalEnergies, the project is minority-owned by private and state-controlled companies from India, Japan, Mozambique and Thailand.

The Export-Import Bank’s 2025 approval of the loan came two months after Donald Trump was inaugurated for a second time, and after a sustained lobbying campaign by TotalEnergies. The French company had spent no money lobbying the federal government since 2019 but then reported spending $500,000 in 2024 and $1.9 million last year, hiring a separate firm to represent its Mozambique subsidiary.

Supporters of the loan say that in addition to benefiting U.S. exporters, the federal government’s involvement will promote national interests.

“It offers a foil to China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” said Max Pyziur, senior research director at the Energy Policy Research Foundation, referring to China’s trillion-dollar program to fund and build infrastructure around the world. The foundation’s financial backers include government agencies and the energy industry. “It’s a projection of soft power.”

Among more than a dozen financiers of Mozambique LNG is a partially state-owned Chinese bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, according to AidData. Data compiled by Pyziur shows that the Chinese bank contributed $300 million.

Kate DeAngelis, economic policy deputy director at Friends of the Earth U.S., said the Export-Import Bank’s loan is critical to the project’s success, given its size. Her group wants a judge to force the bank to conduct a new analysis before it disburses the full loan to TotalEnergies. Oral arguments are scheduled for later this month.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,