Laura Ferguson has a strict no-plastic-water-bottle rule when she bikes across Iowa.

She has managed to complete 19 RAGBRAIs—the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa—relying solely on hoses, taps and her reusable water bottles. But on a blisteringly hot Wednesday this July, with 72 miles of Iowa roadways to cover, Ferguson finally caved, accepting an icy-cold bottle.

Ferguson was among over 20,000 cyclists who braved heat advisories, massive storms and surging headwinds to make the 400-mile trek across Iowa this year.

“There are always hard days,” said Ferguson, reflecting on past RAGBRAIs. For over 50 years, RAGBRAI has routed amateur and seasoned cyclists alike from west to east across Iowa. But as the Midwest faces rising humidity and more volatile summer weather, those “hard days” are feeling more intense and more frequent.

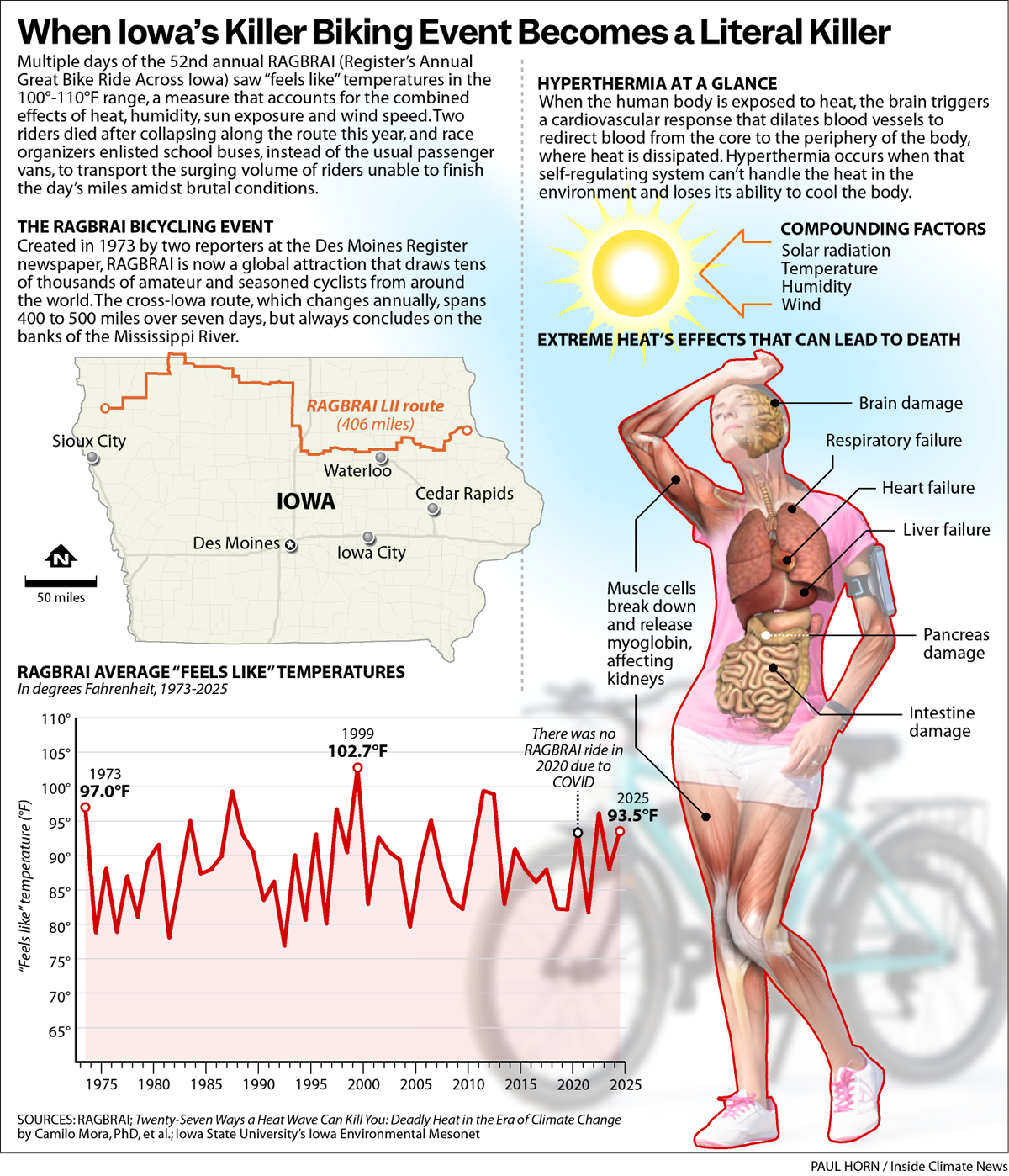

Created in 1973 by two reporters at The Des Moines Register newspaper, RAGBRAI has become a global event, attracting tens of thousands of cyclists from around the world.

The route varies each year, covering 400 to 500 miles over seven days, but always concludes on the banks of the Mississippi River, where riders dip their bike wheels to celebrate.

Participants emphasize that RAGBRAI is not a race, but a festival on wheels. Riders pitch tents in parks and front yards across designated “overnight towns,” while refueling with pork chops, pie, beer and live music.

At 406 miles, this year’s route was the second-shortest ever. It was also one of the toughest. Riders faced multiple days of heat indexes between 100 and 110 degrees Fahrenheit, while battling headwinds up to 20 miles per hour.

Two riders died after collapsing on the route this year, despite receiving immediate medical attention from fellow riders and paramedics.

Originally held the first week of August, RAGBRAI has taken place during the last full week of July since 1980. In that time, maximum summer temperatures in the state have not risen noticeably. Yet the discomfort, or “feels-like” temperature “has definitely been going up,” said Gene Takle, climatologist and director of the Iowa State University Climate Program.

As the rest of the globe warms, the Great Plains region forms what Takle and colleagues have coined a “warming hole.” The term refers to the region where increasing rainfall brought north on winds from a warming Gulf of Mexico has helped to cool off summer days, maintaining long-term averages, all while warming nights and worsening humidity.

Iowa has experienced 16 percent more rainfall over the last 30 years than the historical record, said Takle. A dome of evaporated moisture now travels north from the Gulf each summer, blanketing Iowa in rainfall.

Increased moisture has consequences for RAGBRAI riders. Humidity couples with temperature to create the “heat index,” which is a measure of how hot it feels. Even when daytime temperatures are similar to those of prior years, cyclists experience the heat as more extreme.

Elaine Marzluff, a chemistry professor and friend of Ferguson’s, rode in her eighteenth RAGBRAI this year. The brutal heat reminded her of 2023, when a heat wave made for dangerous riding conditions.

“There’d been the odd hot RAGBRAI before that, but certainly having two in the last few years starts to feel like it’s a lot,” said Marzluff.

Cycling in high heat indexes, especially over multiple days, poses serious health risks, said Glen Kenny, a University of Ottawa scientist studying heat stress.

When exercising in extreme heat, the body attempts to regulate its temperature both by sweating and by pumping blood to the skin, where heat is lost to the surrounding environment. This reallocation of blood flow ups the strain on the heart and diverts blood away from key organs, said Kenny, leading to a physiological “danger zone.”

Meanwhile, humidity can restrict the evaporation of sweat, rendering cyclists damp and still just as hot.

What is particularly dangerous about RAGBRAI and similar activities is the cumulative strain of heat stress over consecutive days, said Kenny. The body needs time to recover from heat, dehydration and muscle fatigue.

For the majority of RAGBRAI riders, who spend all day in the sun and then camp outside, Iowa’s rising nighttime temperatures and humidity affect recovery. “They don’t get that cool-off period,” said Takle, the Iowa climatologist.

Riders from cooler, drier climates are at greater risk of heat-related injuries during the event, said Kenny, the heat stress researcher.

Iowa’s climate can be a real issue for riders from out of state, agreed Ferguson.

“Last year, we met people on the route from some cool, flat, European country and they told us, you can kind of train for the hills, but there is no way to train for the heat,” she said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThere have been over 30 RAGBRAI deaths since the first ride in 1973. Crashes and automobile collisions are an ever-present threat along the route, but so are heat-related injuries, noted Kenny.

Mark Spoo, 62, of Colorado, died of a heart attack on Day 2 of this year’s ride, according to the obituary written by his family. “It was fitting that Mark’s last ride of his life would be RAGBRAI in 2025,” they wrote about the avid cyclist. Thomas McCarthy, 63, of Florida, died after collapsing the following day. His exact cause of death has not yet been released.

Bob Libby, owner of Iowa City-based Care Ambulance, LLC, has provided medical aid to riders during more than 30 RAGBRAIs. The medical transport company began as a RAGBRAI support service, and continues to travel alongside cyclists each year with a mobile fleet of nurses, paramedics and physicians.

As extreme heat persists, riders have gotten better at taking safety precautions, said Libby.

“When it’s hot, what do we do? We spread it all over the news, and everybody gets told to drink lots of water and electrolytes,” he said. “People are a little more prepared for it.”

The growing heat awareness is encouraging, as future RAGBRAIs are unlikely to be any cooler. Temperatures during June, July and August are projected to increase more in the Midwest than in any other region of the United States, according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, published in 2017.

And Iowa’s average heat wave will only get hotter, said Takle. Currently, five out of every 10 years, a five-day heat wave in central Iowa averages 90-95 degrees. By 2050, the average heat wave will be upwards of 97 degrees, he said.

Climate change has also manifested in Iowa as more severe summer storms, said Takle. Heavy winds, hail size and rainfall have all increased, he said.

Many of the communities along the RAGBRAI LII route were hit by damaging storms just one week after riders passed through their towns. Ninety-mile-per-hour winds downed trees and damaged buildings, leaving thousands without power.

Marzluff, the 18-time RAGBRAI-er, worries about what will happen when a catastrophic storm strikes during the ride itself. There are storm shelters and alert systems in each overnight town, but those emergency plans have never had to be tested at full scale, she said.

“I’m just thinking about the point at which the community really, truly just gets devastated, and then you’ve got 25,000 other people there who have to somehow get moved along and be safe,” she said.

RAGBRAI coordinators did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding the event’s response to heat and extreme weather. However, both Ferguson and Marzluff noted several changes to the ride in recent years.

Typically, passenger vans dubbed “sag wagons” sweep the route to pick up riders unable to finish the day’s miles. This year, school buses were used to collect heat-exhausted stragglers.

Free water sources were also more clearly marked, Marzluff observed. “They had more places to [get water] in every town than I remember in any RAGBRAI.”

Like many RAGBRAI riders, both Marzluff and Ferguson see the challenging conditions as part of the experience. The ride is often described as “Type 2 fun,” the sort of slightly miserable adventure that seems pleasant in retrospect. But punishing conditions bordering on unsafe may force future riders to make tough decisions about participating.

“You expect it’s going to be hot,” said Marzluff. “But the question is, at what point does it get hot and uncomfortable enough that it is not as safe to be out there as you would like?”

Correction: This story was updated Aug. 14, 2025, to note that RAGBRAI stands for the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa and travels from west to east across the state.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,