A breadfruit tree stands in the middle of Randon Jother’s property, its lanky trunks feeding a network of sinewy limbs. The remnants of this season’s harvest weigh heavy on its branches. Its vibrant leaves and football-sized fruit may appear enormous to the untrained eye, but Jother is concerned.

They used to be longer than his hand and forearm combined. He points to his bicep, to show how fat they once were. Now they’re small and malformed by most people’s standards here in the Marshall Islands. Mā, the Marshallese term for breadfruit, used to ripen in May. Now they come in June, sometimes July.

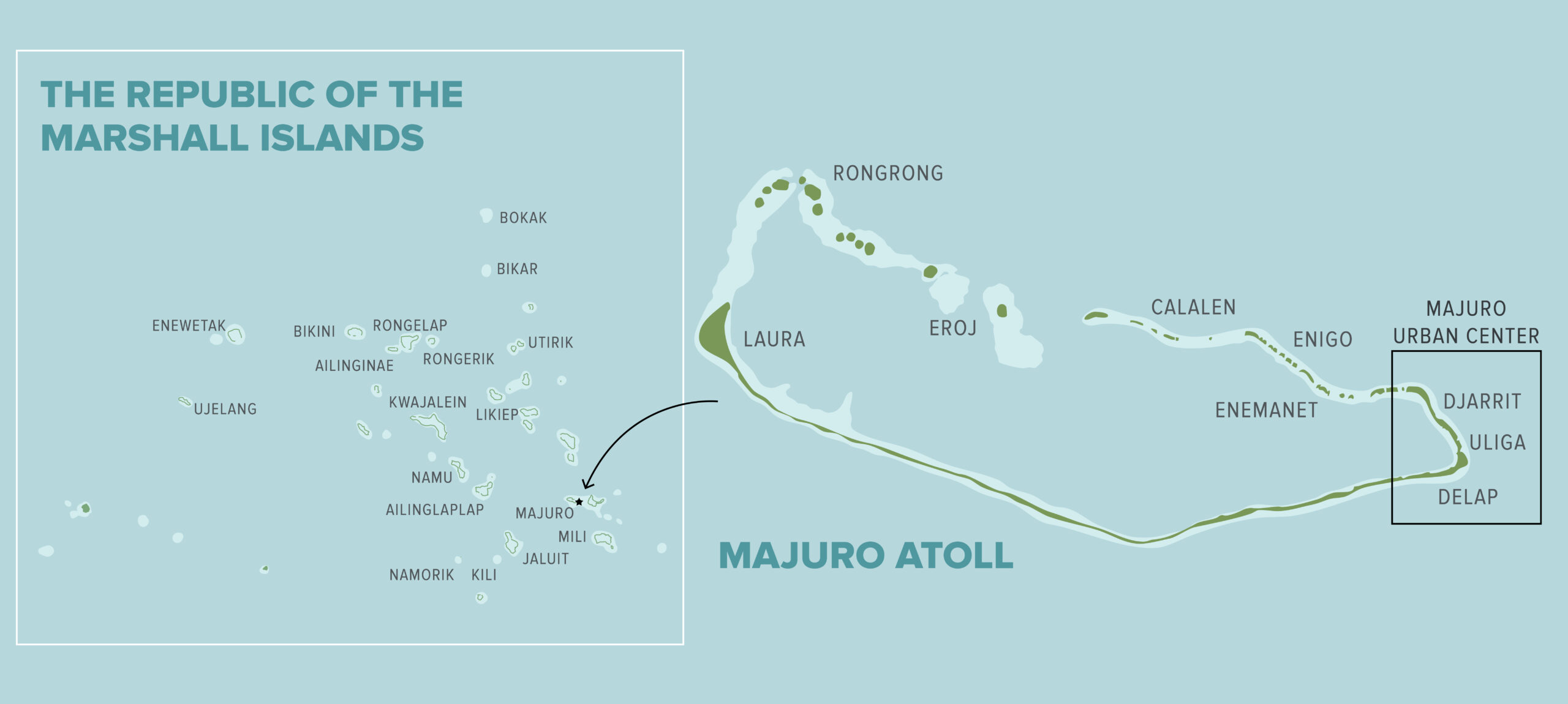

It’s been headed this way for the past seven years, Jother says as he toes the tree’s abundant leaf litter. It’s a concerning development on this uniquely agricultural and fertile part of Majuro Atoll, home to the country’s highest point: eight feet above sea level.

“I think it’s the salt,” Jother says. His home is less than 100 yards from Majuro lagoon, a body of seawater that threatens to overflow onto the land during a storm or king tide, which over the past decade years has happened several times in Majuro and across the islands. The Pacific Ocean also threatens to salt the island’s ever precious groundwater, which Jother says is already happening. When he showers, he can feel it in his hair, on his skin.

The record heat waves, massive droughts and an increasing number of unpredicted and intense weather events don’t help his trees either.

Most assume the assailant is climate change, to which researchers and experts have said the Indigenous Pacific crop would be almost immune — a potential salve for the world’s imperiled food system. For places like Hawaiʻi, they have predicted breadfruit growing conditions may even get better.

But here, on Majuro and throughout the Marshall Islands, the future appears bleak for a crop that has helped sustain populations for more than 2,000 years.

Rice has overtaken the fruit’s status as the preferred staple over the past century, along with other ultraprocessed imports, a change that feeds myriad health complications, including outsized rates of diabetes, making non-communicable diseases the leading cause of death across these islands.

The diseases are a Pacific-wide issue, one Marshall Islands health and agriculture officials are eager to counter with a return to a traditional diet. Climate change is working against them.

Jother is one of few farmers on the atoll able to make his entire living off his land, which produces fruit from six other breadfruit trees, as well as bananas and mountain apples. But he’s fearful about the future of his land – his mountain apple tree is on the verge of death. He’s worried his other breadfruit will suffer, too, and it’s his most lucrative crop.

He’s tried diversifying with western farming techniques but his coral-based soils lack needed nutrients and his suspicion that his water is too salty has grown over the past seven years. That is despite Laura, where he lives, being considered the most fertile of the Pacific nation’s 29 coral atolls and more than 1,200 islands and islets.

As Jother’s niece roasts some of his dwindling stores of the dragonscaled fruit, he considers his options. He’s planning to buy more water catchment tanks, which means he’ll be relying for the first time on increasingly unreliable rainfall patterns to irrigate his trees.

“This is my livelihood,” Jother says. “Without it, there would be nothing.”

A Trinity Of Trees

Mā is part of an important trinity for the Marshall Islands, which also includes coconut (ni) and pandanus (bōb), that made their way to the islands’ shores on Micronesian seafarers’ boats somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 years ago.

Six varieties are most common in the Marshall Islands, though at least 20 are found throughout the islands. Hundreds more breadfruit types can be found in the Pacific, tracing back to the breadnut, a tree endemic to the southwestern Pacific island of New Guinea.

The tree provided security for island populations, requiring little upkeep to offer abundant harvests. Each tree produces anywhere from 350 to 1,100 pounds of breadfruit a year, with two harvest seasons. Every tree produces half a million calories in protein and carbohydrates.

Like many Pacific island countries, the mā tree’s historic uses were diverse. Its coarse leaves sanded and smoothed vessels made with the tree’s buoyant wood. Its roots were part of traditional medicine. The fruit was cooked underground and roasted black over coals. And it was preserved, to make bwiro, a tradition that survives through people like Angelina Mathusla.

For Mathusla, who lives just over a mile from farmer Jother, making bwiro is a process that comes with every harvest.

The process begins with a pile of petaaktak, a variety of breadfruit common around Majuro and valued for its size and lack of seeds. On this occasion, a relative rhythmically cleaves the football-sized mā in half with a machete, then into smaller pieces, before tossing them into a pile next to a group of women. Some wear gloves to avoid the sticky white latex that seeps from the fruit’s dense, white flesh, used by their forebears to seal canoes or catch birds.

Mā trees use that latex to help heal or protect themselves against diseases and insects. The tree’s adaptation to the atolls and their soils has traditionally been partly thanks to symbiotic relationships with other flora.

In those forest ecosystems, lanky coconut palms formed a perimeter and required little fresh water to thrive. The palms were planted to protect the islands’ interiors while pandanus — an edible relative of Hawaiʻi’s hala tree that bears a fruit that looks like Jurassic pinecones — grew below and between. That salt-adapted plant protected the understory and island interior from winds, while other plants like beach cabbage – or beach naupaka in Hawaiʻi – filled the gaps.

Breadfruit populated the islands’ interiors, where the groundwater was deepest.

Today, while breadfruit trees remain common throughout Laura, its underground water supply — a shallow freshwater lens — is diminished by overdrawing and evaporation during record heatwaves and drought, and salinization from the rising seas.

Mathusla lives a stone’s throw from the sea, on the southwestern edge of the crescent-shaped atoll. She watches on as her relatives, sitting cross-legged, remove the remnants of scaly green skin and cores from her harvest, creating a new pile of the fruit. It’s an hourslong task in a weeklong preservation process.

“I do this every season,” she says, fanning herself with a breadfruit leaf the size of her torso. “I don’t like seeing it get wasted.”

A Shallow Body Of Research

Four framed photographs hang on a whitewashed wall of Diane Ragone’s Kauaʻi home. Two black-and-white photos, taken by her late videographer husband, show Jimi Hendrix and Jerry Garcia playing guitar on stage. The other two are of breadfruit.

Now in the throes of writing a memoir, of sorts, Ragone is revisiting almost 40 years of records — photos and videos, and journal entries, some of which leave her asking “Damn, why was I so cryptic?”

But Ragone’s research, since her arrival to Hawaiʻi from Virginia in 1979, forms the bedrock of most modern research into the tree’s history and its survival throughout the Pacific. The most obvious example spans 10 acres in Hāna, on Maui, where more than 150 cultivars of the fruit Ragone collected thrive at the National Tropical Botanical Garden’s Kahanu Garden.

Less obvious is how her work has helped researchers like Noa Kekuewa Lincoln track the plant’s place in global history and the environment. Lincoln, who says “Diane’s kind of considered the Queen of Breadfruit,” has been central to more recent research into how the plant will survive in the future.

Together with others, they act as breadfruit evangelists, promoting the crop as a poverty panacea and global warming warrior — a touchstone for Pacific islanders not only to their past but a more sustainable future.

Ragone, as the founding director of the 22-year-old Breadfruit Institute, helped distribute more than 100,000 trees around the world, to equatorial nations with poverty issues and suitable climes, like Liberia, Zambia and Haiti. But it all started in Hawaiʻi with just over 10,000 young breadfruit.

In some places, rising temperatures and changes in rainfall will actually help breadfruit, according to research from Lincoln and his Indigenous Cropping Systems Laboratory, which assessed the trees’ performance under different climate change projections through 2070.

Running climate change scenarios on 1,200 trees across 56 sites in Hawaiʻi, Lincoln’s lab found breadfruit production would largely remain the same for the next 45 years.

“Nowhere in Hawaiʻi gets too hot for it,” Lincoln says. “Pretty much as soon as you leave the coast, you start getting declining yields because it’s too cold.”

Compare breadfruit to other traditional staples — rice, wheat, soybeans, corn. The plant grows deep roots and lives for decades, requires little upkeep or annual planting, resists most environmental stressors and can withstand high temperatures.

Few nations know the urgency of climate change better than the Marshall Islands, its islands and atolls a bellwether for how heat, drought, intense and sporadic natural disasters and sea level rise can upend lives. More than half of Marshallese people have been affected by coastal erosion, while more than a third say their land is being salinized, according to the latest census.

Droughts have been severe enough for the government to declare a state of emergency, calling on the international community to help meet citizens’ most basic needs as their trees and crops withered and died.

Tidal overwash and inundation is becoming increasingly common, including in 2014, when 1,000 people had to be temporarily evacuated to shelters at schools and churches as waves crashed over seawalls and ran through people’s houses. Another 250 were evacuated to Arno, Majuro’s neighboring atoll.

In typical circumstances, breadfruit is a good choice for such extreme climates, a naturally resilient tree that can withstand heat and drought. Intense babying of the trees during and after dry periods — selective pruning, heavy mulching — has shown promise in Kiribati, another atoll-rich nation to the south of the Marshall Islands.

The trees can even survive some saltwater intrusion, according to Lincoln’s research. But a consistent presence of salt is another matter, attacking the roots and making trees unable to absorb freshwater and nutrients. As roots rot, leaves and fruit die.

“The salinity,” Ragone says, before letting out a sigh. “How do you even address the salinity issue?”.

Marshall Islands government officials have turned to the International Atomic Energy Association for help, asking its experts about using nuclear radiation to create mutant hybrids of the nation’s most important crops — giant swamp taro, sweet potatoes and, of course, breadfruit.

The technique has been used for almost a century by the atomic association and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, predominantly on rice and barley, never on breadfruit or for a Pacific nation.

They have their work cut out for them. To find a viable candidate, immune to salty soils and heat, about 2,000 plants would need to be irradiated, according to Cinthya Zorrilla of the atomic energy association’s Centre of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture. One of those plants, once mutated, might exhibit the desired traits.

Without a government tissue culture facility, let alone a greenhouse, the Marshall Islands’ Ministry of Natural Resource and Commerce is already at a disadvantage. The country’s chief of forestry, Randon Jack, says building the tissue culture lab is his main priority as plants continue to become endangered and extinct.

The process also requires specific expertise and heavy training, which will be needed on Majuro. The Division of Forestry, for example, doesn’t yet have any certified arborists let alone tissue culture experts.

Even if those obstacles were overcome, it wouldn’t be a quick fix. Hybridizing plants through radiation can take about 10 years, Zorrilla says, with a need to compare, contrast and correlate results from labs and field plots and laboratories. For breadfruit, the timeframe may be even longer.

“It’s really complicated,” Zorilla says. “All this is a huge investment, in monetary terms and also in time.”

Land Health Is Human Health

In a whitewalled room, under the buzz of fluorescent light, Jo Dean puts the finishing touches on her garden rainbow soup. “Purple for eggplant, red bell pepper, orange for pumpkin, yellow corn, leafy greens,” Dean says before she begins chopping a pile of amaranth, Asiatic pennywort and other commonly found leaves.

Her audience is a handful of Marshallese, watching as the Australian volunteer discusses the ingredients’ nutritional value. The greens might be familiar to the farmers only as weeds around their plots, but they’re central to Dean and her husband Geoff’s presentation on easy-to-grow, climate-friendly crops found throughout Majuro.

Greens are not naturally part of the Marshallese diet, nor are any of the soup’s other ingredients. They’re mostly foreign foods for a population whose traditional, cultural diets have been usurped by many ultra-processed, carbohydrate, fat and protein rich imports from other countries. The nation currently relies on imports for more than 90% of its food supply, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Breadfruit and taro take a backseat to rice, American chicken and pork have replaced fish-rich meals. Powdered drinks like Tang and Kool-Aid are Marshall Islanders’ greatest source of Vitamin-C.

At stores like K&K Island Pride Super Market in Majuro, canned goods dominate the shelves. American chili, tuna from the Solomon Islands, Australian corned beef along with SPAM, are stacked high. The freezers are filled with turkey tails, pork ribs and chicken. Cabbage and carrots and lettuce sit in the produce section, along with Ecuadorian bananas, American apples and oranges — all rotting. At the back of the store, bags of Filipino and American rice are stacked high.

Rice is central to every meal, accounting for one in four calories consumed by Marshallese. Its convenience, consistency and cost is hard to beat, just over a century since rice was first imported to the islands by the Japanese, who — like the Germans, Spanish and Americans — temporarily colonized the islands. It makes up 41% of the average Marshallese daily calorie intake.

Substituting rice for breadfruit has created a nutritional vacuum in Marshallese diets since it is devoid of the Pacific staple’s complex carbohydrates. Breadfruit also contains 18-fold the fiber of rice, 12 times more potassium and five times more calcium. It provides protein and antioxidants, which rice doesn’t.

It may not be a surprise then that the Marshall Islands has among the world’s highest rates of diabetes, heart disease and obesity, and that one in three children is obese, has stunted growth or is emaciated. The average life expectancy is 66, more than a decade younger than in the U.S.

Agriculture and health authorities have looked to the country’s history to resolve the nation’s chronic health issues, advocating for their traditional nutrient rich starches to retake their place as the belly-filling commodity of the islands.

The national government has been working alongside international development agencies to spread the word, through public messaging about the health benefits of consuming more fruits and vegetables, as well as promoting their cultivation.

Some produce in grocery stores is locally grown, though the lion’s share is imported. Everything from green beans and romaine lettuce from the U.S. or other importing countries rots on the shelves, both undesirable and cost-prohibitive for locals. The same produce, grown on Majuro, has an even higher price tag in part because of low supplies.

“Our people are not green leaf eaters,” says the country’s natural resources secretary, Iva Roberta. “If you go to a home, it’s just rice and the meat. Rice, meat, rice, meat, maybe some breadfruit but no vegetables.”

Foster Manwe, a farmer watching the Australian’s presentation about climate-friendly crops, encourages his family to eat well and consume little rice. He grows everything from breadfruit and giant swamp taro to eggplants and cucumbers, along with pigs, chickens and their eggs. Manwe’s farm is the most productive in Laura, which means it’s likely the most productive in the country.

Most of Majuro’s population does not have access to such abundance. Nor do they worry about the prospect of losing breadfruit or other traditional crops, Manwe says, because they believe the supply chain for rice and other imports won’t break. That has historically been true: They still had imports after occasional missed harvests on Majuro or Kwajalein atolls, where food arrives with just about every inbound flight.

But in 1999, the atoll ran out of rice for two months. And with climate change forecasts predicting not just global rice shortages but disasters debilitating airports and seaports, imports are not infallible.

So while local crops or imported food could theoretically act as a backstop for each other during shortages, neither are the perfect fail-safe.

Manwe hails from Majuro’s northerly neighbor, Aur Atoll, so he understands the other Marshall Islands’ ongoing reliance on tree crops and how climate change can be particularly devastating in places that lack power and running water.

Manwe recounts his time surveying all the nation’s inhabited islands in 2019, during a particularly devastating drought. The islands’ groundwater became undrinkable, rain catchment dried up, trees suffered, their leaves browned and fruit dropped early.

National and island governments distributed or loaned desalination technology to those islands — close to 25 machines, including two for Aur Atoll — but a few years later the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies found many had broken down due to a lack of maintenance.

Again, in 2024, an additional 15,000 Marshallese were struck by drought, this time including Majuro, although it didn’t reach the same extreme levels.

Could it get to a point where local food stops growing?

“Maybe,” Manwe says. But it won’t really affect Majuro, “because we have access to food. But up (north), not so much.”

Marshallese tend to have a degree of pragmatism about the signs of climate change. Some are counting down the years until they have to desert their home islands. That’s the case for Kirenwut Anjain of Mejatto in Kwajalein Atoll, who was visiting Majuro for a church conference.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowWhile spending the past week at the conference, she has been preserving breadfruit in her downtime to feed the congregants.

Bwiro, once a necessary staple, is now primarily reserved for special occasions on Majuro. Anjain has been making it at the home of her extended family in Laura, improvising with trash bags filled with saltwater instead of marinating the fruit in the ocean.

She lifts the fruit from the bag, then punches it down into a cooler. It looks like mashed potatoes and smells like fresh sourdough bread. Traditionally, the mash is buried in a hole lined with breadfruit leaves but the cooler will do the same job.

It’s ready to cook, Anjain says. It doesn’t matter when, she says. Today, tomorrow, next week, next month, or even longer. It will keep.

Where Anjain lives, on Mejatto, bwiro remains more of a necessity. The island is home to refugees from the island of Rongelap, evacuated 40 years ago because of American nuclear testing and the subsequent fallout.

Rongelap has known plentiful harvests but even it is becoming less hospitable. The heat is too much, Anjain says, the coastal erosion and sea level rise is creeping in, and even the resilient plants are acting fishy.

Anjain leads efforts to maintain hydroponic tower systems donated to her island in 2023 by the United Nations Development Programme. The 30 towers were to be used to grow tomatoes, cucumbers and other less familiar foods, like melons and bok choy.

Like the trees and ground crops, the 18 still-functional systems need water — 24 gallons every week. Anjain draws the water from wells around the island, which she says is becoming brackish.

But Anjain will deal with whatever obstacles come her way, including the prospect that catchment water might be needed for the hydroponic system. What they will be, “Only God knows,’ she says. “We’re relying on God’s plan. We don’t know what’s going to happen.”

‘It’s Only Here’

Droplets of rain wet Malo B-Lakien’s Hawaiʻi-branded T-shirt, worn over her typical Marshallese dress, navy and adorned with flowers. She would be soaked if she weren’t standing under her family’s sprawling breadfruit tree.

She has known the tree for most of its life, since moving in with her husband three decades ago. His grandmother planted the tree, which was barely up to B-Lakien’s shoulders at the time. The tree has since fed her family and the neighborhood with a twice-annual harvest. Lately the fruit has featured less in meals.

The community is worried about her tree, she says, as they are about the many other breadfruit trees dotting Djarrit, an urban neighborhood about 30 miles west of Laura, in Majuro’s urban heart, known as Delap-Uliga-Djarrit. Named for three islands once separated by tidal seas, the now connected islands are home to the government, the national hospital and the country’s largest population, including migrants from other Marshallese islands.

Many move to Majuro from the outer islands in search of work opportunities, though a growing contingent are coming because the climate on other islands is becoming unlivable. Driven by drought and its downstream effects, as well as flooding and food insecurity, researchers predict thousands of Marshallese islands will meet that fate — or disappear into the sea entirely — over the coming century.

With migration comes a change of lifestyle, as the outer islands’ population largely subsists on the fruit of trees, along with occasional imports of rice and other global commodities.

More than 65% of rural households subsist on wild foods or grow their own, and fish, according to the Marshall Islands’ 2021 national census. On Majuro less than 20% of people fish, grow food or forage.

Trees have given way to buildings, paved over by development and changing priorities. That leaves the remaining trees more vulnerable than ever. With fewer coconut palms and pandanus, the breadfruit are exposed to the whipping, salty winds blowing in from the Pacific.

Looking up from beneath B-Lakien’s sprawling tree, it appears healthy. Its canopy stretches 30 feet, shading her single-story home and hanging over the road. But from a distance, the tree’s upper reaches look like many in the urban area: Sea winds have shaved the leaves from branches and stems. Last year’s heavy drought only hastened the tree’s steady decline.

Many of the urban trees are completely naked, like deciduous trees in winter even though they are evergreens. Finding a source for the traditional foods in is becoming harder.

“If you travel to Tonga, you travel to Samoa, Vanuatu or the Solomon Islands, you go to the farmers markets and they’re huge,” natural resources secretary Roberta says. In contrast, on Majuro, there are few sources for locally-grown foods.

In rural Laura, on a daily basis, an island-government truck picks up women from around the neighborhood to bring them into town for a small market. They load the truck with breadfruit, bananas, foraged clams, taro and cooked variations of what grows on their properties.

For the women, it’s an important additional source of income in a male-dominated job market; for city dwellers, it’s a rare source of Marshallese comfort food.

“They don’t get this at the grocery store,” vendor Elizabeth Marques says. “It’s only here.”

On Sunday, the women stay in Laura and the customers come to them. They open for business as soon as church services end, stocking government-built blue huts scattered throughout the area.

A recent returnee from California, where she lived and worked for decades, Marques now drives taxis and sells produce from her family plot to help make ends meet.

As a repatriated citizen, she is a rare case in the Marshall Islands. The number of Marshallese moving to the U.S. is consistently rising, having increased by 20,000 in the past decade, while in the islands the population has dropped by almost 20%.

“Every Marshallese coming home from the U.S., they all come — from the airport to here,” Marques says. “They miss the food.”

Marques moved back in 2021, after her brother was murdered, to take care of her family’s land. They grow eggplants, tomatoes, cucumbers and the traditional crops. By mid-July, Marques doesn’t have any breadfruit left from the most recent harvest, though she recalls that what she picked showed signs of stress.

By about 3 p.m. on one recent Sunday, the stalls are almost sold out. Bellenina Bokna had started out with 11 roasted breadfruit and 40 coconuts and now is left with some young coconuts, two hands of bananas, a bottle of clams, a few bags of chips and a cooler filled with a drink made with the marshmallow-like center of sprouted coconuts.

When money’s short, Bokna knows she can forage clams in the ocean or pick fruit from her trees, two of them breadfruit. She feels lucky to be able to rely on the land to feed herself but, like many of her vendor colleagues, is hoping her misshapen and small breadfruit starts to recover.

“I’m worried,” Bokna says, looking into the distance.”But what can I do? We have no power to change it.”

“Hawai‘i Grown” is funded in part by grants from the Stupski Foundation, Ulupono Fund at the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,