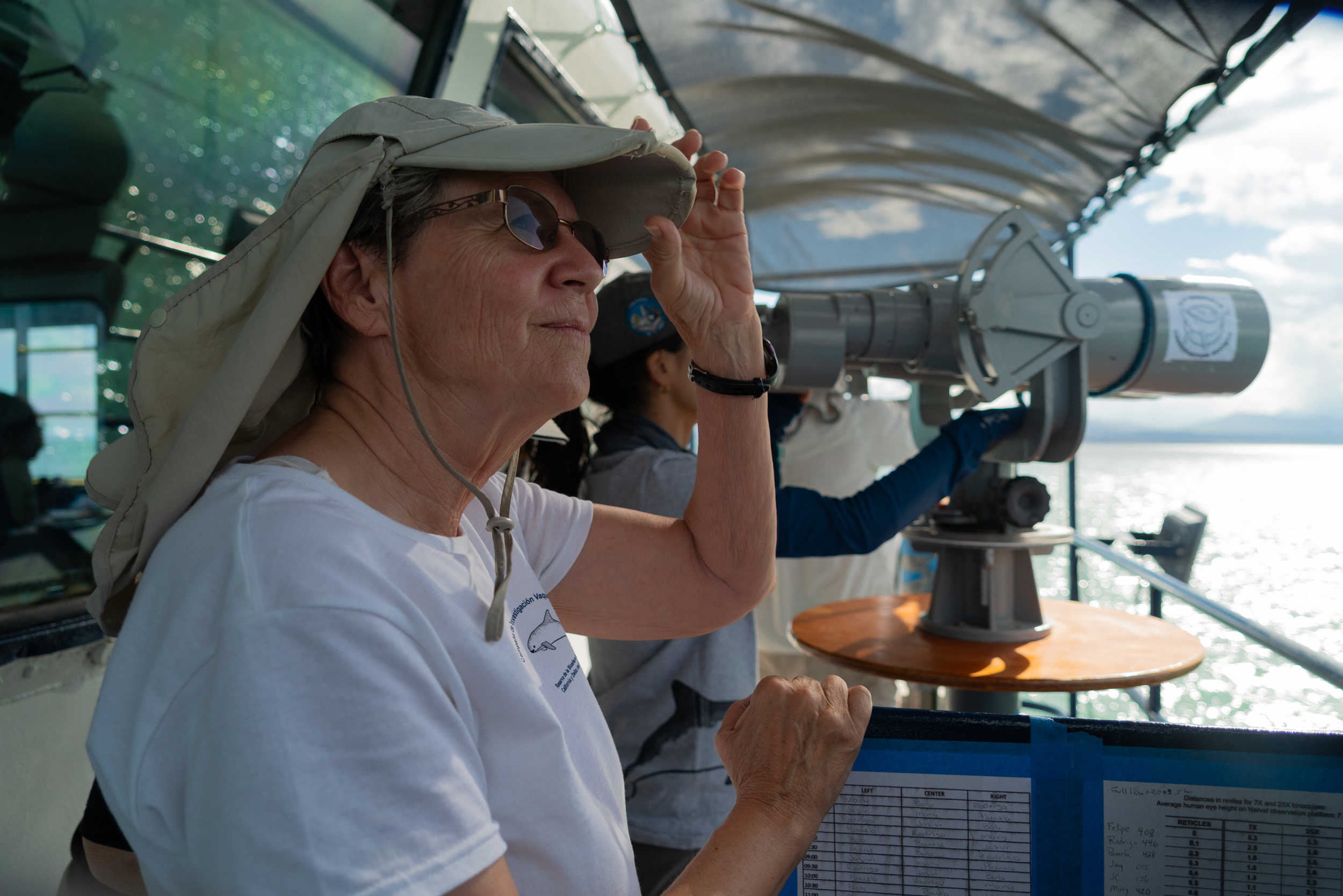

To spot a vaquita porpoise requires calm winds, clear skies and waters smooth as glass. But in September, those conditions were hard to come by off the coast of San Felipe, a small fishing town in Baja California, Mexico. It was hurricane season, and for most of the month strong winds churned up heavy swells as a group of veteran marine mammal researchers conducted an annual survey of the rare marine mammal—a challenging task, even in the best of conditions.

“There’s nothing harder than vaquita to find and to track,” said Barbara Taylor, a biologist from Montana who has been monitoring whales, dolphins and porpoises for more than 30 years. “They’re really, really difficult to see.”

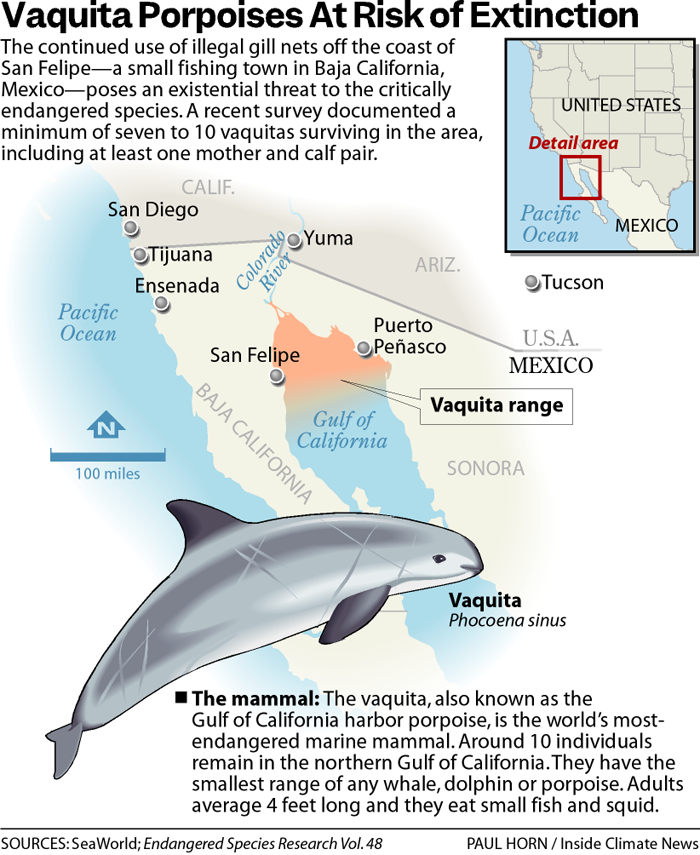

They are only about 4-5 feet long and surface only briefly to breathe. Their small gray bodies blend in easily with the turbid sea. “If there’s any swell they just disappear,” said Taylor, who helped lead the survey. Plus, there’s only a few of them left. The vaquita is the most endangered marine mammal on Earth.

Found only in the Upper Gulf of California, the vaquita has been pushed to the brink of extinction by the widespread use of deadly fishing gear called gillnets. These walls of mesh hang like invisible curtains in the sea and are used by fishermen to trap shrimp and fish that become entangled in their webs. But the nets are “non-selective,” Taylor said. “They just kill everything.” From sharks and rays to whales, sea lions, dolphins and vaquitas, few animals that cross paths with the gear escape its grip. Most suffocate and drown as they struggle to break free.

“The greatest risk factor, not only for vaquita, but for all marine mammals, probably seabirds and sea turtles, are gillnets,” said Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, a biologist from Mexico, who also helped conduct the survey. He works for Mexico’s National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP), a federal agency responsible for conserving and managing the country’s natural protected areas.

Although Mexico permanently banned gillnets nearly 10 years ago, both Rojas-Bracho and Taylor said weak enforcement and a lack of alternative fishing gear have allowed their illegal use to persist, even inside the federally protected vaquita refuge, a 500-square-mile area of water where fishing is supposed to be prohibited.

The Annual Vaquita Survey

Annual surveys of the endangered vaquita have become a cornerstone of international efforts to save the species. Since 2018, a team of leading cetacean experts has gathered each year in San Felipe—pausing only during the Covid-19 pandemic—to search for the remaining porpoises. The surveys are designed to track the animals’ health, movements and exposure to illegal fishing activity. Assessing population trends, reproductive success and where the animals face the greatest risk of entanglement within the refuge helps shape conservation strategies, Taylor said.

This year, to better their chances of finding the elusive animals, they planned one of their longest and most robust surveys yet in collaboration with the Mexican government and the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, an international nonprofit that runs a year-round campaign to protect the porpoises called Operation Vaquita Defense.

Sea Shepherd is the only organization that maintains a 24/7 physical presence inside the vaquita refuge, where its crew pulls up gillnets and patrols the area with onboard radar, sonar and drones to detect illegal fishing, which they report to the Mexican Navy so it can intervene.

“We are like the eyes of the vaquita refuge,” said Andrea Bonilla, the organization’s lead scientist, who helped coordinate logistics for September’s survey.

For most of the month, the crew lived and worked on board two Sea Shepherd vessels, the Seahorse and the Bob Barker, named after the late animal rights activist. They used high powered binoculars called “big eyes” to scan the horizon for glimpses of the porpoises’ dorsal fins slicing through the silty Gulf waters framed by desert mountains.

Some of the team focused on listening for the animals using special acoustic devices that detect and record underwater sound. Like many cetaceans, vaquitas use echolocation to navigate, communicate and hunt. By emitting high-frequency clicks and listening for the returning echoes, they are able to get a sense of their environment and locate prey, including small fish, crabs and shrimp, even in murky shallows.

By noting where in the refuge these sounds were detected, the researchers were able to focus their visual search. This process, Taylor said, allowed them “to be in the right place and not have to just sort of search a big blank ocean.” As a result, she said, despite not having optimal conditions, “We had quite a number of sightings.”

Most of the survey activities took place inside the Zero Tolerance Area (ZTA), a 100-square-mile, octagon-shaped zone within the larger vaquita refuge off San Felipe. The area, established in 2020, was meant to serve as a strict no-fishing zone, protecting the small patch of sea where research has shown most vaquitas still remain. But, for several years, rampant gillnet fishing continued inside its boundaries.“There was so much gillnet fishing that it was really hard for us to operate our surveys, because we had to navigate around all the gillnets, and we could see the Vaquitas right in there with gill nets,” Taylor said.

That changed in 2022, when the Mexican Navy installed hundreds of concrete blocks fitted with metal hooks designed to snag and deter gillnets around the perimeter of the ZTA. Since then, officials have reported more than a 90 percent drop in illegal net use within the zone. “All of a sudden you go from something that’s a Zero Tolerance Area on paper to a real sanctuary for Vaquitas,” Taylor said.

But, based on the most recent visual sightings and acoustic detections of vaquitas, Taylor said it’s clear that some of the animals are moving just outside the Zero Tolerance Area. These findings suggest protections like the cement blocks and hooks may need to extend beyond its current boundaries.

In addition to looking for the animals, the team also tried to identify each of the individuals they saw. That way they could determine if they had been seen in previous years, or if they were new ones that had yet to be identified. It was a way to track their survival over time.

To do this, the team tried to photograph each of the animals with long telephoto lenses or drones. They could later analyze the photos and distinguish individuals by their distinctive fin shapes and scars or notches etched into them. “We thought that we could use photo identification to estimate the numbers of vaquitas and be able to really follow individual fates, which I think is really not only important for science and conservation, but also, I think it makes them much more understandable to the public and to the local community,” Taylor said. One way to make them even more relatable, she said, was to give them names.

Signs of Hope

Towards the end of the month on a rare clear day, the team experienced one of their most memorable encounters.

“We had a mother and calf that were close enough to see with the naked eye, which doesn’t happen with vaquitas very often,” Taylor said. Unlike most of their previous sightings, which typically lasted less than a minute, this pair lingered near the surface long enough for researchers to capture clear drone footage of them swimming together. The adult female was one they recognized by her distinct bent dorsal fin. “We named her Frida after Frida Kahlo, because Frida was also wounded, but had a very important life as a leader of Mexican culture,” Taylor said.

This was the third year in a row they had spotted Frida, and the second time she was with a calf, which the group estimated was about a year old—a hopeful sign, Taylor said, being that many young die in the first year or two of their lives. From the drone footage, she added, it looks like Frida may even be pregnant again.

“What we’re seeing is so encouraging that we have these females that are reproducing as fast as they can and their young are surviving,” Taylor said during a press conference about the survey results in late October. “I think their recovery could be on the optimistic end, but still, right now it’s the time to work on the human dimension of the problem.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowBy the end of the expedition, the team estimated they had seen between seven and ten individual vaquitas, including one or two calves. Because it’s not always possible to distinguish between individuals, the scientists report a range of estimated sightings rather than an exact count.

It’s important to note, Rojas-Bracho said, that these numbers do not reflect the total population. They should be interpreted as a “minimum number of surviving vaquitas.” Though, he added, it’s likely there aren’t many more. Last year’s survey recorded between six and eight individuals—a reminder of how fragile the vaquita population remains.

Vaquita Defense

When Rojas-Bracho first began studying the species in the late 1990s, there were roughly 600 vaquitas. Since then, their numbers have fallen by more than 90 percent, in large part due to illegal fishing of totoaba, an endangered fish, endemic to the Gulf, that can grow bigger than the vaquita. The nets fishermen use to catch these fish are some of the largest and deadliest.

The fish’s swim bladder—believed in traditional Chinese medicine to have healing properties—can sell for thousands of dollars on the illicit market, fueling lucrative international trade, despite global bans on its sale and trade. According to NOAA Fisheries, fishermen can earn up to $8,500 for just two pounds of the dried bladders—roughly half a year’s income from legal fishing.

“If we want to save the vaquita, we have to eliminate the traditional fishing nets, and in particular these, which are the most lethal, the totoaba nets,” said Rojas-Bracho. “As long as we don’t do that, the population will continue to be at risk of extinction.”

But the only way to eliminate them, he said, is to develop alternative fishing gear that not only poses less risk to marine life like the vaquita, but is favorable to the fishermen, too. It needs to be affordable, effective and available. And so far, he said, that type of gear just doesn’t exist, making it nearly impossible to enforce Mexico’s ban on gillnets.

In announcing the survey results, Marina Robles García, undersecretary of biodiversity and environmental restoration at Mexico’s Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), said the government is now developing and testing alternative gear designs. But this is not a fast process.

“These cultural changes ultimately take a lot of time,” she said. “One thing I think is in our favor is that the conversation with the fishing communities is ongoing and has been very positive. We’re not in a confrontational situation, but rather one of coordination.”

Meanwhile, the Mexican Navy confirmed it’s stepping up enforcement efforts, requiring more than 800 small fiberglass fishing boats, known as pangas, to be fitted with satellite trackers that will show their movements inside the vaquita refuge. The system began rolling out earlier this summer.

But for the immediate future, said Rojas-Bracho, the Mexican biologist, the core challenge for the vaquita’s survival remains unchanged. “There will be no alternative fishing gear this year or next year,” he said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,