CHAUNCEY, Ohio—This village sits between the Hocking River and a tributary, Sunday Creek. When they flood, they can completely submerge the two roads connecting the village to the highway.

The evacuation route for such occasions ends in another floodplain. With enough rainfall, residents could conceivably find themselves stuck. Many don’t even know about the evacuation route in the first place, according to Chauncey code inspector Drew Daniels. He said he’s heard of people risking a $2,000 fine—and their personal safety—trying to drive through floodwaters to reach the highway instead.

In the spring, Daniels met with the Athens County planner and emergency management agency about mapping out new flood routes for Chauncey (pronounced CHAN-see) and sharing them with the public. However, they quickly realized the Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps the county has traditionally relied on didn’t provide enough information.

“Once we actually sat down and talked about it, we realized, well, flooding happens in different places. This flood route might work if there’s riverine flooding, like if the Hocking River level has just gone up a lot, but if there’s flash flooding, parts of West Bailey Road [the evacuation route] could get washed out with a surge of water,” Daniels said. The FEMA map doesn’t show that kind of water movement.

The challenge of doing something as basic as updating flood routes reflects growing uncertainty about where flooding can actually occur and who is at risk—concerns worsening as climate change fuels stronger precipitation and catastrophic floods more often make the news.

FEMA flood maps, while still useful, have significant limitations: They only use historical rainfall data, which may not reflect the changing climate. And they only map incorporated communities in detail—95 percent of Athens County is unincorporated, according to county planner Connor LaVelle. There is a pressing need to fill the gaps.

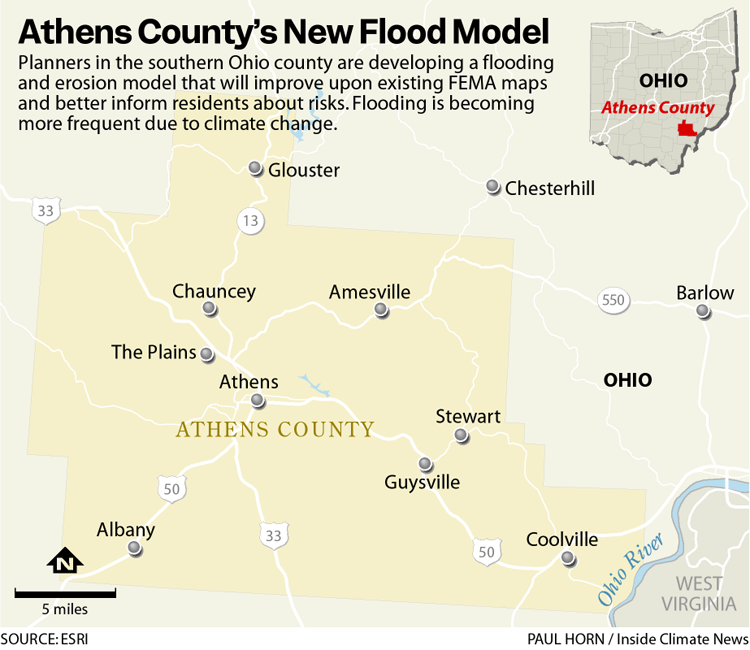

That’s why Athens County is now taking the unusual step of creating a county-wide flooding and erosion model. Unlike the FEMA maps, the new model will calculate possible future rainfall scenarios, and it will map every part of the county in detail, not just incorporated areas.

The aim is to identify better flood routes, ensure residents know the real risk of their properties flooding and locate sites for effective mitigation projects—for example, the creation of a new wetland that captures floodwater upstream.

Right now, there are residents living outside FEMA-mapped areas who have no idea their homes may be susceptible to flooding, said County Commissioner Chris Chmiel.

“The current FEMA flood maps, they don’t really touch the little tributaries,” Chmiel said. “People build their houses and put their trailers in those areas, and those places flood, and then those people, they lose their housing.”

Chmiel said several properties in the county have been left uninhabitable by flooding. The county land bank has been buying those properties and tearing them down.

LaVelle said residents who don’t realize they live in a floodplain face real risks.

“If they were unaware … when they’re building, they could even go so far as to build a basement for this home, which you obviously wouldn’t be allowed to do if it was a regulated floodplain area. And they could have their utilities down there,” LaVelle said. “[The water] could get into their home. It could also damage their appliances and their utility connections, and it could, they could potentially be”—he paused—“trapped until the water goes down.”

Poorly planned construction can also push water off one property and onto another located downstream, thereby increasing the risk for others. For these reasons, anyone building in a floodplain is supposed to follow certain guidelines. For example, they may have to elevate the building above where the water is likely to rise.

LaVelle said he can only enforce those guidelines if he has evidence that the property is in a floodplain. If FEMA hasn’t mapped it, then legally, there is no such evidence—unless he has a model like the one now being developed.

The county is working with a local sustainable development nonprofit, Rural Action, and the engineering consulting firm BSC Group to create the model. It is an expensive undertaking for a rural area and relies on a $117,000 grant from the national Climate Smart Communities Initiative. Getting it done will require assembling and analyzing reams of data about factors like topography, soil type and existing development, as well as information from community members about where they have experienced flooding themselves.

A BSC engineer will then use that data to simulate what happens with varying levels of rainfall.

“The model will think about, how quickly is that water running over the land? How does that interplay with the water in the river rising? How much can the soil and the land absorb?” said BSC’s director of climate resilience services, Katie Kemen.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe end result will be a two-dimensional digital model showing the extent and depth of flooding at different precipitation levels throughout the county. Kemen said exactly what precipitation levels the model includes will be determined with input from the community.

That information can then inform decisions about how to prepare the county for floods. Those preparations could include more accurate flood routes, as well as sites for “green infrastructure” that captures water and reduces flood levels.

“So, planting more trees … their roots will absorb water. More vegetation, having rain gardens and bioswales, which are depressions in the terrain that water can get pulled into,” Kemen said.

The model could also identify sites for wetlands restoration, which can play a significant role in redirecting floodwater.

“Historically, rivers were very meandering, and then they had their floodplains, and when there was a flood, they would kind of spill out and the land around the river would absorb the water,” Kemen said. “When we developed, we developed in a lot of straight lines, and so we channelized water, we put it into culverts, we put it underground, and the water still wants to go where it went.”

In theory, the model could even show what would happen in a rainfall event like those seen recently in Texas, Kentucky and North Carolina. However, LaVelle, the county planner, said modeling alone won’t make the county prepared for such a disastrous flood. Instead, it will create an important reference point for the people who are trying to prepare for such an event.

“What we are looking for is solid data to make sure that development projects are being done in a way that are aligned with our floodplain regulations,” LaVelle said. “The regulations that you have for your floodplain are a community’s first line of defense against that kind of problem.”

Kemen said the model will be publicly available by next summer.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,