MOSS LANDING, Calif.—A snarl of steel and debris still sits front and center at the Moss Landing Power Plant, after one of the largest battery fires in the world burned here a year ago.

The damage, cloistered behind guarded gates, is one of the few visible remnants of the historic inferno. Surrounding the plant, life appears relatively mundane. Birds wade in a nearby estuary and visitors mill about at the local marina.

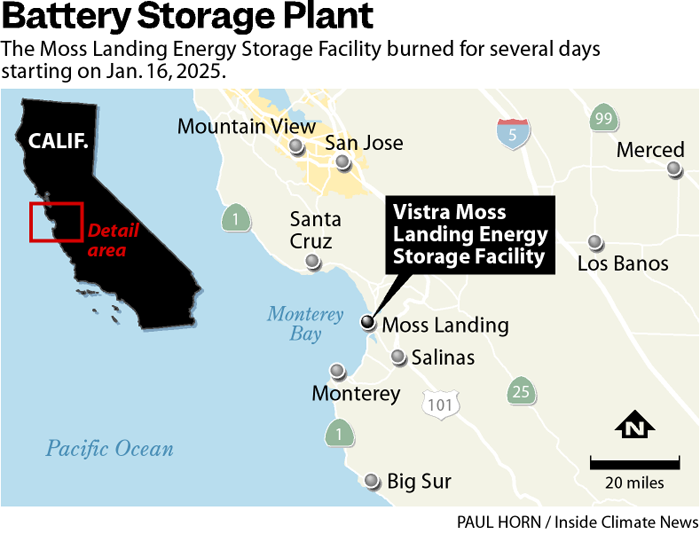

On Jan. 16, 2025, the Vistra Moss Landing Energy Storage Facility, about 20 miles south of Monterey, burned for several days and distributed a fine layer of heavy metals across the landscape. Today, a cleanup of the facility is ongoing as long-term health and ecological impacts remain uncertain.

“It’s been a long year. There’s a lot of unanswered questions,” said Glenn Church, District 2 supervisor of Monterey County. The cause of the Vistra fire is still unknown. The blaze—which burned anywhere from 55 percent to 80 percent of the site’s 100,00 lithium-ion batteries—was one of the largest fires at a battery storage facility to date, if not the largest.

Lithium-ion batteries, which also contain toxic chemicals and metals, are essential for the green energy transition, serving as the dominant technology in electric vehicles and storing excess electricity for wind and solar facilities for use when the sun isn’t shining or the wind drops.

A spokesperson for the California Public Utilities Commission, which has been investigating the fire, told Inside Climate News that the agency does not have a timeline for when the cause of the fire might be determined, and that its investigation is ongoing.

Delays by the state of California in its investigation worry Church. “If we continue to have fires, we continue to have incidents like this … you’re going to have the public lose faith,” he said.

Brad Masek, Vistra’s renewable operations director, wrote in a letter to the community published on Thursday that “air, water, and soil testing by multiple agencies over many months have found no risks to public health or agriculture related to the fire.

“Additional monitoring and testing continues under the supervision of the U.S. EPA on site and the Monterey County Environmental Health Bureau in the community,

and the results gathered to date have been reassuring and consistent with previous findings,” Masek wrote.

The cleanup of the facility began in September. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, more than 15,200 battery modules have been de-energized for recycling. So far, there have been no flareups during battery removal work. Stabilization and demolition of the facility began in December. The EPA estimates that further demolition, which will remove the severely burned section of the building, will begin in mid-2026. The building will be demolished to its foundation.

In his letter to the community, Masek said that cleanup efforts will shift later this year to the portion of the Moss 300 building that burned. “Accessing this area of the building will help advance the investigation into the fire’s origin, as the damaged portion of Moss 300 may hold information that our investigators need to complete their work,” he wrote. “We are all eager to have answers as soon as possible, but we must conduct this investigation thoroughly. That takes time. Battery energy storage is vital to the future of California’s electric grid, and a thorough investigation will help the entire industry enhance its safety practices.”

“New Territory”

Residents of Moss Landing remember watching a plume of ash and smoke grow as the fire burned into the weekend. The fire lasted for roughly three days and reignited briefly again in mid-February. Flames shot up the side of the facility’s decommissioned smoke stacks. Battery debris and ash settled on the surrounding wetlands. Businesses and locals have sued for damages.

Eventually, more than a thousand residents were temporarily evacuated. Shortly after the fire, the EPA said that there was no risk to public health, though many would report rashes, sore throats and headaches following the blaze. Some with pre-existing conditions noticed that their symptoms worsened and new ones appeared.

“My life and the life of my family is measured by before Jan. 16, 2025, and after,” said Brian Roeder, co-founder of Never Again Moss Landing, a local advocacy group that formed after the fire burned.

Roeder said he and his family began to notice health impacts following the blaze. Roeder was struggling to breathe, his wife’s pre-existing conditions flared up and his son started to cough. “We abandoned our house twelve days after the fire,” he said.

The family bounced between Airbnbs and eventually sold their house at a financial loss, worried about the health effects that they had endured. “ We don’t know the long-term impacts of what we inhaled. We know that what we inhaled was incredibly toxic,” Roeder said.

Recent peer-reviewed research shows that after the fire, a thin layer of dust containing heavy metal particulates settled in Elkhorn Slough, the protected estuary adjacent to the battery storage facility.

Ivano Aiello, a professor in marine geology at San Jose State University’s Moss Landing Marine Labs, was evacuated from his lab when the fire started. As soon as the evacuation notice lifted, he headed to Elkhorn Slough to test the soils for particulates. He remembers burned ash and battery remnants littering the field site. To date, his research is the only study that has examined the impacts of a large-scale battery fire.

“The silver lining of all this is that we are charting new territory on something that’s going to be so dominant in our life, which is energy storage,” said Aiello.

Aiello notes that his study only scratches the surface of potential impacts from the fire. He estimates that the metals detected only account for 2 percent of potential particulates. “ What we found [in Elkhorn Slough] was a fraction of what potentially could have been released,” he said.

Recent testing, conducted by Vistra’s consultant, Terraphase Engineering Inc. and released by Monterey County’s Environmental Health Bureau, shows no widespread contamination, though elevated cobalt, lead and/or manganese were detected in a select number of samples. The Central Coast Water Board has requested further water and soil testing from Terraphase. The board cites issues with water filtering methods and the depth of soil testing, which may have diluted samples.

Aiello and a team of researchers continue to study the long-term impacts of the fire to see how and if the metals are moving or concentrating in the ecosystem. “We are gaining important information that can be beneficial for other accidents,” he said.

Uniquely Catastrophic

The Vistra fire was uniquely catastrophic. In the years leading up to it, there had been several high-temperature incidents at the Vistra Moss Landing facility that did not result in a fire. In 2022, a small fire occurred on site at the PG&E Elkhorn Battery Facility, which is not operated by Vistra and located in an outdoor array. The Vistra Moss Landing fire was the largest incident by far.

Many battery storage facilities are located outdoors, where groups of batteries are siloed away from each other. This arrangement generally helps to create a stopgap against catastrophic events. Moss Landing 300—the Vistra building that caught fire—contained an array of tightly packed batteries located in a decommissioned and converted gas-fired power plant. Experts say that storing batteries in large indoor installations, like Moss Landing 300, can make fire safety difficult.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowVistra Moss Landing also used nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, which are less stable than their newer—and industry favored—counterpart, lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries. The facility’s outdated indoor arrangement and dated battery chemistries, industry experts have said, made the Moss Landing configuration uniquely dangerous compared to newer installations. Regardless, the Vistra Moss Landing fire has left many around the county fearful of new battery installations.

To date, indoor battery installations are still permitted in California. The state has established a battery storage safety collaborative to examine battery safety and risk. State representatives have also introduced legislation to further regulate battery storage facilities, including limiting their proximity to environmentally sensitive sites. The legislation did not pass in the 2025 session.

Overall, constituents feel left behind and ignored. “What we want is for the state to walk and chew gum at the same time,” said Roeder. “To both be committed to carbon neutrality, but also come back to this community and learn from what happened to us.”

This article has been updated to include portions of a letter to the community published by Vistra on Thursday.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,