Most days, researcher Stefan Tucker, with trawls, trammel nets, trot lines and even electrofishing gear, is on his boat looking for sturgeon in the Rock River. The nearly 300-mile waterway winds through Illinois’ northwest corner, at depths between 15 to 50 feet, flowing and gurgling from Wisconsin down to the Iowa border, where it joins the Mississippi River.

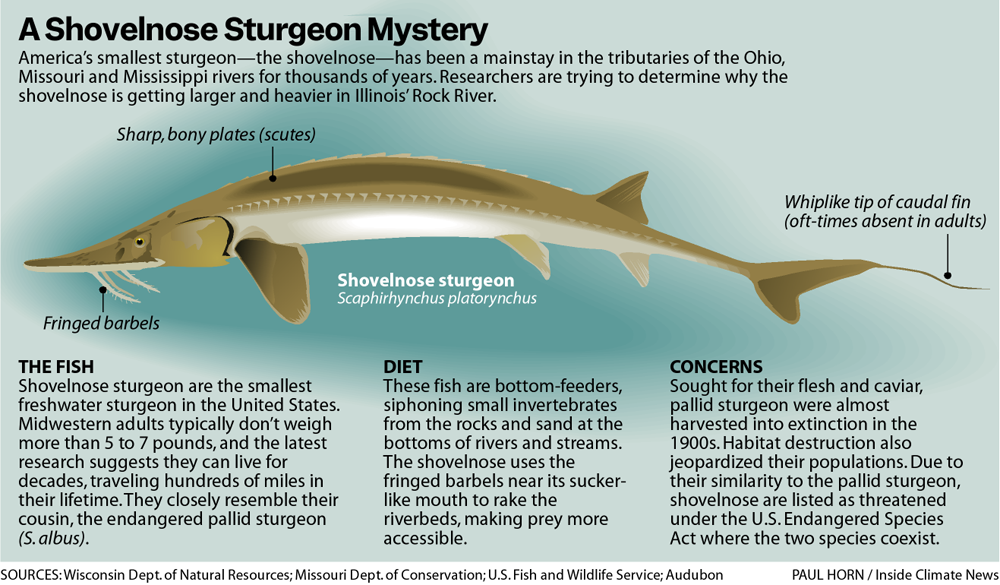

Tucker is a fisheries ecologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey, and the sturgeon he seeks are the most abundant, and the smallest, in the country: the shovelnose. A species that lived with dinosaurs, the fish has a large nose, bony scoops instead of scales that can destroy fishing gear and fringed whisker-like structures near its mouth.

Shovelnose typically tip the scale at about seven pounds, but the Rock River fish are surprisingly sturdy, hauled in at record weights year after year. That’s what drew Tucker and the Illinois research institute to spend years gauging the fish’s unusual vitality.

“The population here is pretty novel,” Tucker said. “And it’s understudied.”

When anglers began regularly pulling hefty-sized shovelnoses from Rock River—catching fish weighing up to 10 pounds—the Illinois Department of Natural Resources made sturgeon throughout the river a research priority. In 2022, the agency tapped Tucker, a sturgeon specialist, to investigate the shovelnose in the Mississippi River tributary.

Tucker co-published his first results this summer, revealing that of the 1,324 shovelnoses caught and included in the research effort from 2022 to 2024, a whopping 22 percent were 31.8 inches or longer. Usually, just 1 percent of shovelnose sturgeon populations hit that size. Over the next three years, Tucker will be fishing for more shovelnose as well as reasons why the population is so robust.

“If we can study a healthy sturgeon population and really understand these population dynamics,” Tucker said, “we can then look at other river systems, and identify differences and potential problems, then propose solutions on how to mitigate those problems and enhance that specific population.”

Sturgeon across the globe are the most endangered group of fish, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Fishing, manmade dams and pollution have contributed to falling populations across all 27 sturgeon species. Warming waters from climate change also threaten some species, research shows.

And sturgeon species are among the most prized of catches. Fishermen harvest shovelnoses for their roe, one of the top three species of wild-sourced caviar. The global market was valued at $97 million in 2022 and is expected to grow to $160 million by 2032, according to Allied Market Research.

As sturgeon populations fell drastically over the last few decades in global waters, particularly in the Caspian Sea, pressure shifted to other sturgeon species like the shovelnose.

Fishing industry concerns about shovelnose sustainability in the Midwest in the early 2000s prompted state agencies in Minnesota, Iowa and Indiana to embark on studies. Researchers found that fishermen could harvest shovelnose sustainably, but commercial operations meant that the shovelnose sturgeon in those areas would likely grow more slowly.

Research now focuses on the ecology and environmental conditions that affect shovelnose populations and how to protect the fish, said Jeff Koch, assistant director of fisheries research at the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks, who participated in the 2000s studies.

“Of the 20-some sturgeon species worldwide, the majority of them have decreased to a level where they’re listed at some level of conservation status,” Koch said. “We didn’t want to see that happen with the shovelnose.”

What Tucker has found so far in the Rock hints to some factors that keep their populations going strong. The fish in his study area seem to thrive despite the physical barriers like dams. Notably, commercial fishing is not permitted in the Rock, which may allow the fish to mature, reproduce more often and build bulk, scientists say.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowBut figuring out how long it takes for a population to mature poses a challenge because it’s difficult, generally, to determine growth rates and ages for sturgeon. Recapture is one fishing method to measure growth. But when researchers catch, tag, release and then recatch fish, recapture rates in some places are only about 10 percent.

Otoliths, or inner ear bones, grow each year in fish and are marked by rings, much like a tree trunk. Scientists studying samples collected from captured shovelnose believed the bone rings showed the fish live for about 15 years. But the aging estimates are tricky because shovelnose ear bones are made of different material than most other fish. Then, three years ago, Ryan Hupfeld of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources used evidence from atomic bomb testing to produce a more accurate estimate.

Nuclear bomb testing conducted all over the world in the 1950s and 1960s caused a steep rise in carbon-14, a radioactive isotope in Earth’s atmosphere that slowly declines over time. It turns out that fish absorb carbon-14 into their ear bones, which researchers can compare to the atmospheric carbon-14 levels in the atmosphere over the same period.

Scientists have calculated the age of other fish, such as Greenland sharks and bigmouth buffalo, using the radioactive signature. Hupfeld experimented in 2022 with shovelnoses caught in Iowa’s Cedar River and saw a surprising result: Some of the fish were as old as 40.

“We’re underestimating the age by potentially double, especially on the older fish,” said Hupfeld, who is now the Mississippi River habitat coordinator for the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. The method is accurate within a few years, he said.

Hupfeld’s aging research and Tucker’s population and gender ratio information could help conservation efforts across several states—or at least help fisheries biologists determine the best way to manage the populations in the upper Mississippi. State agencies across the region are working to harmonize harvest regulations, which could affect other shovelnose populations.

In Iowa, for example, the minimum size limit for commercial fishermen fishing for shovelnose is 27 inches. In some Illinois rivers, it’s 24. Scientists estimate that shovelnoses grow 0.12 inches a year, so a difference of three inches could mean that fish in one state could live 25 years longer than in another—making for a mature population that could readily and repeatedly spawn.

Tucker said the work, over the years, should offer insight into population dynamics and the environment needed for the highly valued fish. All of these small variables, and how they work together, he said, play into the larger story of population stability and persistence in the Rock River. “We’re letting the science guide the next steps of our research.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,