SHELBY, Wis.—If she closes her eyes, Danelle Larson can still remember how the stretch of Mississippi River in front of her looked as recent as a decade ago: nothing but open, muddy water.

Today, it’s covered with impressively tall and thick beds of wild rice.

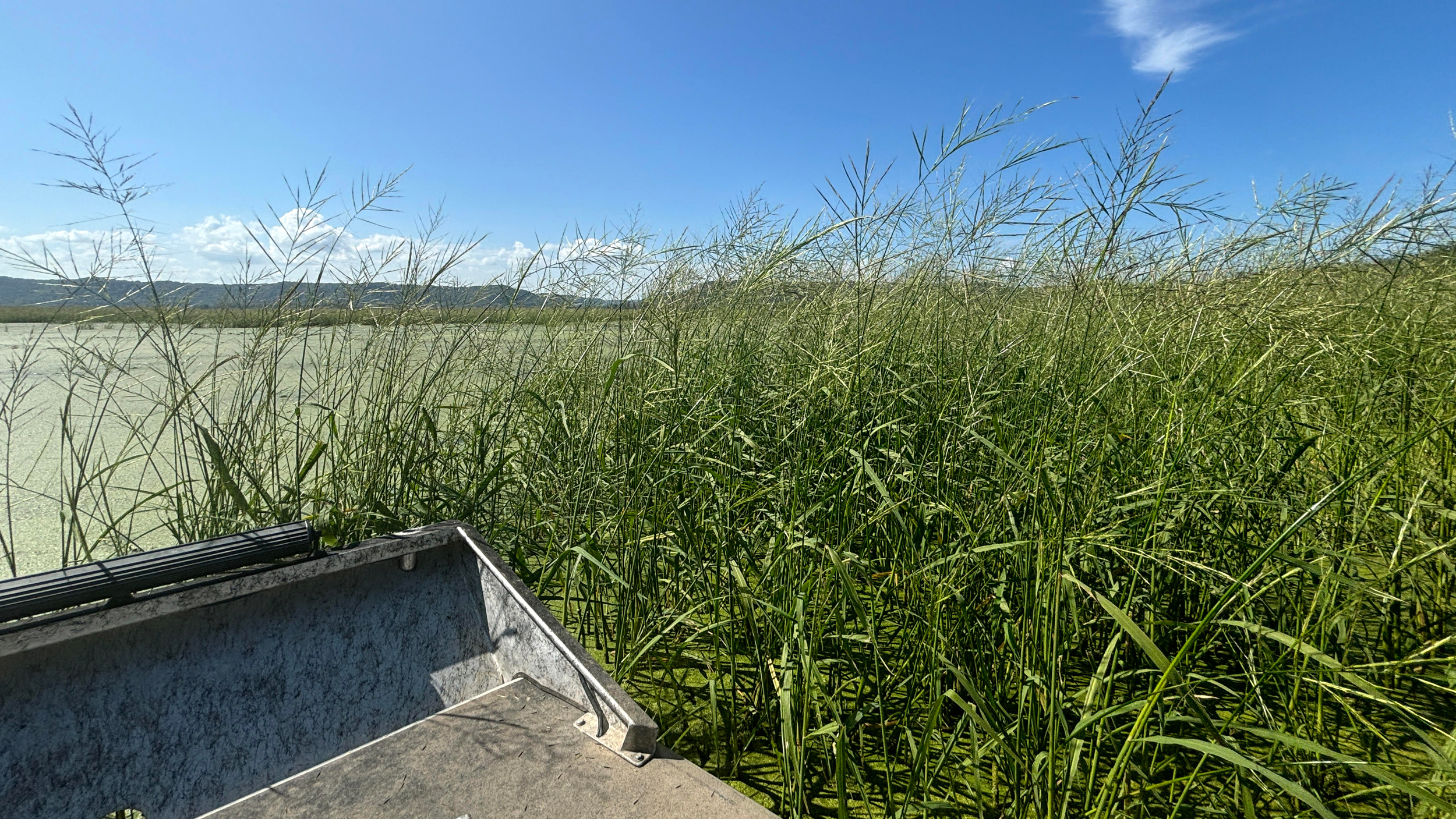

Larson, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, and Alicia Carhart, Mississippi River vegetation specialist for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, surveyed the plants by airboat in mid-September. Summer floods on the river delayed growth somewhat, but the tall green shoots still waved in the breeze in almost every direction off the shores of Goose Island County Park near La Crosse.

“It’s one of the most dramatic changes on the upper Mississippi,” Larson said. “It’s everywhere.”

In the past several years, wild rice has exploded on this part of the upper river, particularly on a section of it called Pool 4, near Alma, and Pool 8, near La Crosse. Historical records show it was common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but poor water quality and other problems caused widespread aquatic vegetation die-offs in the 1980s.

For some, the resurgence is a source of wonder. For others, it’s more of a nuisance, making it hard to maneuver boats through areas that were once easily passable.

But what’s driving the substantial increase in growth is still largely a mystery.

Mississippi River Wild Rice Is Tall, Resilient and Expanding Fast

Wild rice is an annual plant, meaning it completes its entire life cycle in one growing season and then dies. The seeds germinate in spring, then sprout to lie flat on the water like ribbons during their floating-leaf stage. During the summer months, the plants emerge from the water, and new seeds ripen and drop into the river in early fall to start the process over again.

The place now known as Wisconsin has a rich history of wild rice harvesting dating back thousands of years with the Menominee, the original people of the area who were named “People of the Wild Rice.” Wild rice, or manoomin, is also closely associated with Ojibwe tribes who arrived in Wisconsin hundreds of years ago in search of “food that grows on water.”

Today, it’s still a central part of tribal diets and identity, but it’s facing serious threats from climate change, fluctuating water levels and human interference. This year, storms and heavy rains in June negatively impacted wild rice production across northern Wisconsin.

The rice growing on the upper Mississippi is different. It can reach about 12 feet tall, while plants in northern Wisconsin lakes are typically waist-high—far easier to shake into a boat to harvest, Larson said.

And it appears to be more resilient to water fluctuations. Carhart said everything she’s read about wild rice would indicate it’s extremely sensitive, but much of it survived the high water earlier this summer—and last year, when the river was in drought, it was more prevalent than she’d ever seen.

“That’s what’s maybe most confusing,” she said. “The rice just seems to be doing well regardless.”

This year, wild rice was identified at 30% of the DNR’s 450 regular sampling sites on the river near La Crosse, Carhart said.

Data from a wide-ranging 2022 report on the upper river’s ecological status and trends backs this up—prevalence of wild rice in pools 4 and 8 increased by “an order of magnitude” in the past decade, the report’s authors wrote, covering thousands of hectares.

The greatest changes have occurred in places where rice has moved into deeper waters, Carhart said. Previously, wild rice was most commonly found in the still, shallow backwater areas of the river. Now, it’s thriving just as much in the river’s main channel, where the water moves quicker and is disturbed more regularly by boats and wind.

The rice appears to be “marching downstream,” Larson said, appearing sporadically on the river down to Wisconsin’s border with Illinois. It has not yet been identified farther south on the Iowa-Illinois border.

Better Water Quality Could Be Driving the Increase

The 2022 report noted that aquatic vegetation in general is thriving on the upper Mississippi between Wisconsin and Minnesota, and water clarity has improved.

Such an improvement may be making it easier for wild rice to establish, but the fact that it’s surging in some places and not others means there’s probably more to the story, Carhart said.

Others think it may be linked to sediment building up in the backwaters, making them shallower and more amenable to the wild rice plant.

Larson said she hopes to do more research about the rice’s habitat preferences to learn more about why it’s increasing in some areas and not others.

She also wants to know more about what kinds of animals use the wild rice and for what purpose. It’s an important food source for ducks, for example, and marsh birds like to hide in the dead stalks as the weather turns colder.

Wild Rice Is Just One Way the River Is Changing

Not everyone is thrilled with the rice’s expansion—particularly those who’ve watched the water they used for recreation turn into a giant rice bed. Lake Onalaska, a large reservoir of the river, is one such place.

In the 1980s, there were a few stands of wild rice on the lake, said Marc Schultz, chairman of the Lake Onalaska Protection and Rehabilitation District. It started expanding about a decade ago, “almost with a vengeance,” he described.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe rapid change even triggered now-dispelled rumors that people were intentionally planting wild rice in the lake.

The problem is that Lake Onalaska is a major draw in the region for fishing and boating. Despite having established “boat channels,” the rice just keeps growing, Schultz said, making it difficult for boaters to get from one side of the lake to the other—or even from their dock to the boat channel itself. And while the lake district can pay to clear it, that’s costly.

Schultz said he’s long viewed wild rice as a valuable resource. But he sympathizes with people who have seen changes to the river accelerate in recent years because of climate change and land use changes.

“They look at rice and say, ‘That’s just another one of those things that’s changing everything,'” he said. “You can understand why people have a lot of concerns.”

This summer’s flood cut back some wild rice growth on Lake Onalaska, but Carhart said she met with the group last year to hear out their worries.

She asked them to consider what the lake might look like if it was all gone—the water would be more turbid, for example, and fish that like clearer water could be driven away.

Larson recalled what the river used to look like when she was a kid: muddy and not safe to swim in.

“Now, it’s pretty crystal clear,” she said. “The plants seem to love it too.”

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri Support our independent reporting network with a donation.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,