One of the most profound shifts in how the United States manages wildland fire is underway.

Federal wildland fire forces are spread across several agencies, closely collaborating but each tackling prevention and protection somewhat differently. Now, the Trump administration is creating an entirely new “U.S. Wildland Fire Service” to combine as much of that under one headquarters roof as it can.

A firefighter with decades of federal and local experience says he has been tapped to head that agency, news that heartened much of the wildfire community when it broke just over a week ago.

The country’s wildfire management system is strained by a steep, long-term rise in highly destructive blazes, and firefighters have spent decades pressing for reforms. Some believe this effort could provide the accelerant needed to see them through. But the muddled rollout of these plans—along with widespread layoffs at agencies that fight wildfires and a crackdown on efforts to combat the climate change that’s fueling the flames—have sowed concerns that this is not the right administration to carry out such a significant transformation. When it comes to wildfire, mistakes can be fatal.

In April, a leaked draft of an executive order from President Donald Trump outlined a plan to restructure the federal firefighting system and prioritize the “immediate suppressing of fires.” This triggered backlash from many fire experts, who feared a return to outdated fire management approaches that focused on putting out wildfires while neglecting practices that better protect fire-threatened communities in the long run.

Two months later, Trump issued a formal executive order, which noticeably avoided any language related to suppression. However, the directive kept its call for the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture to “consolidate their wildland fire programs to achieve the most efficient and effective use of wildland fire offices” within 90 days—a deadline that required that work to be done in the heart of the country’s most active time of year for wildfires.

While the full overhaul the order demanded hasn’t happened yet, the agencies shared their vision this fall. The USDA, home of the U.S. Forest Service, and the Interior Department, which has four other land-management agencies that fight wildfires, outlined a joint plan that aims to “modernize and strengthen America’s wildfire prevention and response system.” That includes developing a joint federal firefighting aircraft service, updating technology and, most notably, announcing plans to launch the new U.S. Wildland Fire Service at the Interior Department in January.

Brian Fennessy, chief of the Orange County Fire Authority in California, told his staff in a Dec. 5 letter that he was selected to lead it, though Interior has not yet made an official announcement and did not answer Inside Climate News’ questions about the matter. The new service doesn’t formally fold in the Forest Service’s fire operations, which are the largest in the country—that would likely require congressional approval. But the plans call for collaboration between the agencies.

“For too long, outdated and fragmented systems have slowed our ability to fight fires and protect lives. Under President Trump’s leadership, we are cutting through the bureaucracy and building a unified, modern wildfire response system that works as fast and as fearlessly as the men and women on the front lines,” Interior Secretary Doug Burgum said in a press release accompanying his order detailing the change.

But many experts worry that these changes are being done with too much speed and far too little planning or resources.

The Trump administration’s unilateral decision to make major cuts this year at land management agencies including the Forest Service and National Park Service drastically reduced the number of federal employees who can prevent and fight wildfires. The cuts have also triggered confusion as agencies rush to fill critical but suddenly vacant roles and have not been clear about how many firefighters the federal government needs or even has. A recent report says the U.S. has done far less this year to mitigate the risk of future wildfires by reducing hazardous fuels on federal lands, a claim the Forest Service disputes.

A number of fire experts, researchers and current and former staff at the Forest Service and National Park Service told Inside Climate News that these moves—as well as major changes to land management practices this year—could hobble the country’s ability to prepare for and respond to wildfires. And all of this is coming as rising temperatures and widespread drought feed the flames.

There is “a lot of fear and unknowns in a system that is highly necessary to run on all cylinders,” said Vicki Christiansen, who served as the chief of the Forest Service from 2018 to 2021, during the last Trump administration. “People’s lives and livelihoods and our critical natural resources of the nation are at stake.”

A New Vision

Under the Trump administration’s new plan, firefighters at the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, all part of the Interior Department, would be housed at the new wildfire agency.

Currently, federal wildland firefighting operations are shared by those agencies and USDA’s Forest Service. They manage wildfires across roughly 640 million acres of public lands, more than a quarter of the country.

Collaboration is necessary no matter how the federal forces are organized. They frequently work with tribes, states and county fire management offices to deal with blazes. The Federal Emergency Management Agency—which Trump has flirted with eliminating—also contributes to this system, providing grants for mitigation that can reduce the severity and destructiveness of wildfires, helping to coordinate evacuations, supplying equipment for firefighters and supporting recovery efforts after fires.

“You cannot look at one agency or one land ownership and say they are exclusively the ones involved in that wildland fire management,” said Christiansen. “It takes all of us, meaning state, local, federal, Tribal, NGOs, contractors, all the rest—no one organization can do the preventative work or the response work.”

In recent decades, fire prevention and mitigation has dominated the Forest Service’s mission. Last year, the agency asked for $2.6 billion for wildfire operations—more than seven times what it spent suppressing fires during an average year in the 1990s. In recent years, the Forest Service has allocated around half of its budget to fire-related activities that took up about 15 percent three decades ago.

It’s not yet clear how Forest Service wildfire operations will change under the new plan, but recent actions hold clues.

In May, the Trump administration released its 2026 budget proposal, which outlined a plan to move the Forest Service’s wildfire suppression operations to Interior to create a single, combined Wildland Fire Service there. Two months later, the House Appropriations Committee pumped the brakes on that move. Instead, the committee directed the Trump administration to first commission an in-depth study on the feasibility of combining operations under the Interior Department.

The plan released last month keeps the Forest Service’s firefighting operation separate from Interior. Asked if the Trump administration still plans to eventually move it, a USDA spokesperson sidestepped the question, saying in a statement that the agency’s “focus is on modernizing support across agencies, not transferring operations, and ensuring effective collaboration through 2026.”

The wildfire community has mixed feelings about the push to consolidate—and whether it is even necessary. Agencies under the USDA and Interior already coordinate through the Idaho-based National Interagency Fire Center, which was established in 1965.

While there are still differences between the agencies, “cooperation is pretty much seamless,” Stephen Pyne, a global fire expert and emeritus professor at Arizona State University, said in an email. “Improving fire management doesn’t seem an adequate justification for the overhaul. I suspect other agendas are at work.”

Former Forest Service firefighter Luke Mayfield is ready for the change—with some caveats. He’s the president of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, a nonprofit made up of active and retired federal wildland firefighters that, since its creation in 2019, has advocated for a unified wildfire agency.

“We need an administrative system that applies to all federal wildland firefighters and provides cohesion and standardization across all levels,” said Mayfield. Transformation will take time, resources and good planning, he added. “There will be growing pains.”

His group endorses the selection of Fennessy to head up the new wildland fire service, particularly noting his experience leading fire teams in California.

“I think it changes the game,” he said. “Fire leaders need to be in charge of firefighters.”

The choice stands in contrast with many of the nominees Trump appointed to head other agencies this year, a raft of people with much less subject-matter expertise than in prior administrations.

Fennessy’s recent experience in fire leadership is predominantly focused on urban conflagrations such as the fires that tore through Los Angeles County in January, which require very different strategies to combat than wildland fires.

However, he also has experience in the federal fire forces. Starting in 1978, he spent 13 years working on firefighting crews in the Forest Service and the BLM. In an interview in June with Inside Climate News, before the news of his pending job change, he said he left the federal government for the same reasons many firefighters cite: mental health and low pay.

In California, a lower-level employee working at In-N-Out Burger was “making more than a starting Forest Service firefighter,” Fennessy said, referring to the roughly $13 hourly salary.

“I loved my job. But, you know, I [had] a two-year-old kid. My marriage was a wreck, going [away] all the time. So the city of San Diego offered me a firefighter position, and I ended up taking it,” he added. “I didn’t want to. I loved the job I was doing … but that’s the reason I left—I couldn’t support a family.”

There have been some improvements since then. Salaries were boosted temporarily in 2021, then permanently in March. Three months later, the USDA and Interior expanded the mental health services firefighters can access.

Fennessy did not respond to requests for comment after announcing his pending job change, and his current employer said he is not giving interviews about the matter. But he told Inside Climate News in June that he supported the idea of a single wildfire agency.

“I believe there’s no going back once you do it,” Fennessy said in June. “This is major policy change at the highest level. … It’ll be ugly at times, like any change, as things are learned and they develop.”

The nonprofit advocacy group Megafire Action released a report in October saying the current consolidation plan “has clear potential to improve interagency coordination, achieve operational efficiency, and streamline technology adoption across the full spectrum of [wildfire management] operations.” Moving the Forest Service—or at least its fire operations—to the Interior Department would be worth continued discussions with Congress, the group added. A bill to see that move through was introduced in February but has not yet had a committee hearing.

Still, despite support for some of the ideas and for Fennessy’s nomination, a number of fire experts have serious concerns with the Trump administration’s ability to carry out a major change to wildfire management after cutting a vast swath of the employees who help fight the blazes.

“The wildland fire community is freaked out beyond alarm … by all the defunding and downsizing and disruption caused by the DOGE dudes,” said Tim Ingalsbee, a former federal firefighter who is now executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology (FUSEE). Over his career, he has worked in fire operations under both the USDA and the Interior Department.

In early June, Ingalsbee and other members of FUSEE traveled to Washington, D.C., to caution against rushing to combine federal wildland firefighting forces, particularly in the midst of fire season. A week later, the Trump administration dropped its executive order giving agencies just three months to make their overhaul plans, for which it had not allocated any additional funds or staff.

One of FUSEE’s primary concerns about consolidation is the mission impact. Each agency under the Interior Department brings different approaches to wildfire—for good reasons. The National Park Service, for example, seeks to protect communities by maintaining ecological health, while the BLM’s top priority is securing public safety; its website lists fire suppression first among the ways it does so.

“If you’re going to consolidate all these different programs with their different missions … whose fire philosophy is going to prevail?” Ingalsbee asked. His worry is that suppression will win out.

However, Ingalsbee is so frustrated with the current fire management system that he can’t help but see some advantages to a big change. “Trump is a wrecking ball,” he said, but he hopes the Wildland Fire Service can offer a new start that a later administration could improve.

Even so, he fears that consolidation plans could be a guise to fire yet more staff at the Forest Service and other fire-related agencies, which are in flux from the layoffs earlier this year.

“It’s a miracle we didn’t see … absolute disasters or tragedies because it was a lot of chaos and disruption,” he said. “I had a hard time sleeping knowing people that were out there.”

The Interior Department did not respond to numerous requests for comment about how the rollout of the new firefighting agency will be funded and organized.

Cutting Down the Forest Service

Liz Crandall had been hopping around seasonal jobs at different national forests for years before the Forest Service hired her full time in 2023 as a field ranger and forest technician at Deschutes National Forest, a nearly 1.6-million-acre reserve spanning the Central Oregon Cascades. She spent about a year and a half working at her dream job among the lush ponderosa pine and Douglas fir trees, keeping trails clear and helping teach the public about the importance of conservation.

“I love protecting the voiceless, so the trees, the animals—everything that comes with that,” she said. “I think that as somebody who is really a big advocate for environmental protection and education regarding that, it just made sense, and it came so natural to me.”

Crandall also holds a “red card”—the federal certification to fight wildfires—and was pulled off her various posts to help fight fires multiple times since finishing the training for the credential in 2018.

“I’ve been on, I don’t even know how many incidents. I put out so many abandoned fires, like campfires, and I’ve called in lightning strikes that I saw happen,” Crandall said. “I patrolled these really remote areas, I naturally came into contact with fire-related things, and that’s why my red card was really important.”

But when Trump entered office in January, “everything got really weird,” she said. Two months into the year, offices across the Forest Service were asked to compile lists of their probationary employees—those who had started their current jobs within roughly the previous year, and sometimes even before that, depending on the role.

On Feb. 14, Crandall got the call from her supervisor telling her she was fired.

“All of this was so sudden and unprecedented,” she said. “I didn’t have time to save [money]. I didn’t have time to look for another job. It was just sprung on me.”

Crandall was part of sweeping layoffs across the federal government that month. Most employees were told that they were fired based on performance. Crandall’s performance evaluations—which she quickly downloaded before the Forest Service shut down access to her employee portal—stated that she “has a great attitude and represents the best of those in public service.”

In March, Crandall was offered reinstatement after a federal board told the USDA it had to temporarily bring back employees that were part of the Trump cuts. She declined. She had already accepted a new job and said she “didn’t trust the uncertainty and instability of the federal government going forward.”

More than eight months after being fired, Crandall received an email from the USDA informing her that the probationary termination was “not based on your personal performance” and that the agency had updated her personnel file accordingly, but it didn’t provide any further details.

After she was fired, Crandall teamed up with Mikayla Moors, a former Forest Service forestry technician who was also terminated in February, to create a podcast called “Rangers of the Lost Park.” They highlight current and former employees who help manage public lands for federal agencies—and the recent actions that threaten their work.

“It’s the only thing, honestly, keeping me going right now,” Crandall said.

It’s unclear how many workers have been lost from the agencies that contribute to the nation’s wildfire response. But the Forest Service axed about 3,400 workers during that round of layoffs. Many more employees have taken early retirement and deferred resignation offers in recent months, including those in high-level positions that lead responses to wildfire emergencies and require years of training and expertise.

The agency said no full-time wildland firefighters were removed from their jobs as part of the work reduction. But that doesn’t include the red-carded employees such as Crandall in what’s dubbed as the “militia,” a firefighting reserve of biologists, rangers and others who can be pulled from their usual posts to join the wildfire response when the blazes become too complex, large or numerous for the full-time force to handle alone.

High Country News reported in August that the Forest Service lost at least 1,800 fire-qualified workers from cuts, retirements and the voluntary resignations many staff were pressed to take earlier this year. In February alone, the Forest Service pushed about 700 people with red cards out the door, ProPublica reported, citing an agency spokesperson.

The Forest Service told Inside Climate News that all but 28 of those 700 accepted the invite to return. Asked how many of those who returned are still at the agency, the Forest Service did not respond.

In April, all six Forest Service chiefs who served between 1997 and 2025 published an op-ed in the Denver Post denouncing the layoffs and other recent moves that threaten to degrade public lands.

“We believe that the current administration’s abusive description of career federal employees is an unforced and, frankly, unforgettable error. These fired employees, we know from experience, represent the best of America,” they wrote. “To see them treated the way they have been over the past few months is incompetence at best and mean-spirited at worst.”

It’s also made a difficult task harder. Just a few months after the layoffs, Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz put out an open call to former red-carded employees who took the deferred resignation to return in an effort to fill gaps on the frontlines.

Some never want to come back.

Gregg Bafundo was a red-carded lead wilderness ranger with the Forest Service when he was fired, then rehired, then decided to voluntarily resign in exchange for paid leave in April. Since then, he said, he’s received emails about dozens of openings at the Forest Service as the agency stared down forecasts of a volatile fire season.

Bafundo has ignored every opportunity. He stopped receiving emails about jobs in September, which is when his deferred resignation period ended.

“I’m also an immigrant,” he said. “I came to this country from the Netherlands. I became a U.S. citizen and I spent my entire adult life risking my life for people who don’t give two shits.”

People in support of the Trump administration’s firing of Forest Service employees are “screwing themselves over because they’re putting their own property and life at risk from the next big wildfire,” he said.

Holes in the System

At the start of the summer, forecasts of heightened fire risk in California and the Pacific Northwest left politicians there particularly concerned about Forest Service understaffing. On June 11, U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., questioned Schultz at a hearing about the presidential budget request.

“The administration claimed that no firefighters have been fired, but the reality is, on the ground, we have lost workers whose jobs are absolutely essential,” Murray said at the hearing. “The stakes are life and death here, and this really raises serious alarms about this agency being ready for this critical fire season.”

When asked if the Forest Service was ready for wildfire season despite staff shortages, Schultz said yes. But conflicting reports of exact staffing numbers in recent months have not eased concerns.

As of Aug. 25, the Forest Service had approximately 11,400 wildland firefighters onboard nationwide, slightly exceeding the agency’s goal of 11,300, according to a statement from the Forest Service sent to Inside Climate News. A spokesperson said by email that the recruitment target is “designed to ensure we can meet the demands of a typical fire season while maintaining readiness across regions.”

But experts familiar with the target-setting process say this goal is mostly based on historical data, rather than reflecting current needs in an increasingly severe fire landscape.

“There’s no rationale,” said Mayfield, with Grassroots Wildland Firefighters. “It’s not justified anywhere.”

This target also does not reflect the support staff needed for fire prevention, mitigation and suppression.

“Firefighters don’t get in the engines and staff the Hotshot crews and jump out of the airplanes and all the other things that they do without a system behind them,” Christiansen said. “That’s what is not talked about when all these [deferred resignation program announcements] came through.”

On its website, the agency acknowledges that even though the goal was met, there isn’t “enough capacity to meet the needs of the continuing wildfire crisis.” As of mid-August, the agency was still seeking to fill fire-related roles around the country, according to emails obtained by Inside Climate News. Those unfilled positions included hotshot superintendents, fuels technicians or officers and fire engine operators. With so many agency workers laid off or taking deferred resignations, Mayfield questions whether the support staff can still ensure firefighters are getting paid or that enough equipment and water is supplied during active fire suppression.

“I’ve been told that the largest affected support mechanisms that we lost were people in the finance realm and resource advisors,” he said. The Forest Service says it has “11,300 firefighters, but there’s a lot of administrative staff above that makes sure that 11,300 firefighters get paid, have food, get taken care of. So it’s just another ripple effect.”

Some remaining personnel at the Forest Service and National Park Service, who asked not to be named out of concern for their jobs, said staffing cuts have undermined their teams’ abilities to respond to wildfires. Hiring was blocked at national parks for more than half the year.

The Forest Service was hemorrhaging staff long before Trump started his second term. During the past four years, according to a letter sent to Trump administration officials by Democratic senators in February, the attrition rate for Forest Service firefighters was 45 percent. Some crews reported that their staffing had been reduced by 30 percent even before the Trump administration cut the federal workforce.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThat means recent layoffs and early retirements have compounded the stress on an already stretched system. Because there’s so much collaboration across agencies on wildfire, shortages on one team can stress others.

Christiansen compares the response system to the game of Jenga, in which each wooden block represents a component that keeps the whole thing running—from staff to funding to logistics. With so much strain this year, Christiansen wonders: Which removed block will topple the whole thing?

Earlier this year, Forest Service numbers showed it lagging on critical efforts to prevent future fires by thinning overgrown forests, clearing dry brush and conducting prescribed burns, according to a report published by Grassroots Wildland Firefighters at the end of October.

Analyzing publicly available data, the group found that these hazardous-fuel projects are down 38 percent as of September compared with the same period in the previous four years.

“Funding cuts have already led to a steep drop-off in forest mitigation projects across the West,” Bobbie Scopa, a retired firefighter with 45 years of experience who is executive secretary of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, said in a statement. “Without the prescribed burns, fuel break and fireline construction, and brush clearing that the firefighters rely on, wildfires will be harder to contain, and our firefighters and communities will be at greater risk.”

On Dec. 2, a group of nine senators, led by Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), wrote a letter to the Forest Service’s chief demanding an explanation for this lag.

“The steep decline in hazardous fuels reduction efforts on Forest Service lands poses a serious risk to public safety, public health, and the economy,” the letter reads. “It is imperative that the Forest Service works closely with Congress to address shortfalls in wildfire mitigation and ensure staffing and budgetary resources are sufficient to fulfill the agency’s mission.”

The Forest Service told Inside Climate News that Grassroots Wildland Firefighters’ report “did not reflect final accomplishment numbers, which were delayed by the government shutdown.” A spokesperson said the agency ultimately doubled the fuels reduction reflected in the report, covering more than 3.25 million acres in the fiscal year 2025, which the Forest Service said is close to its target.

“Looking at a single metric overlooks broader outcomes: In 2025, proactive forest management and aggressive initial attack kept acres burned to nearly half the 10‑year average, while post‑fire restoration reached its highest level in 25 years,” a Forest Service spokesperson said in an email. “Timber production also exceeded targets, contributing to healthier, more fire resilient forests. There is no question, the Forest Service delivered one of its strongest performances in nearly a decade.”

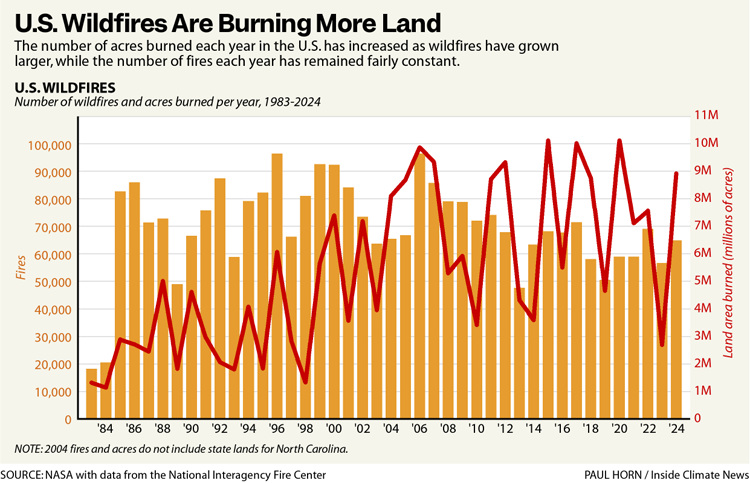

After the devastating Los Angeles fires in January, the fire season that followed has been calmer in many areas than early forecasts predicted. As of Dec. 12, this year’s wildfires have burned through more than 4.9 million acres across the country—far fewer than the nearly 8.5 million acres scorched by the same date last year.

For this season, some “regions may have had cooler and wetter conditions, while others didn’t have as many extreme wind events (and/or ignitions to coincide with them),” Max Moritz, a wildfire expert at University of California, Santa Barbara, said over email. “It’s possible that initial attack also contributed in some regions, but I don’t know if there are studies to substantiate that. The idea that [commercial] timber production would lead to less area burned is not generally accepted.”

Indeed, experts see this relatively calm fire season as a lucky break rather than a sea change. Wildfire seasons can be highly variable. Case in point: Acres burned by wildfires dropped dramatically in 2023 to 2.7 million before skyrocketing the following year.

That’s why it’s so important for federal officials to keep the long run in mind. Affecting that long run are the ways past decisions are making present fires so much worse.

Playing With Fire

Wildfires are a natural part of most ecosystems, burning through grasslands and forests to pave the way for new life. Many Indigenous peoples have understood this for millennia, igniting what have come to be called “cultural burns” to improve the lands where they live, farm and hunt.

But modern society’s relationship with wildfire is centered around one concept: control.

“We don’t like fire because it’s messy, it’s unruly, it’s unpredictable, it’s potentially dangerous,” ASU’s Pyne said. “At any point, you want to control it. Rather than defining it as a companion or best friend—it’s our worst enemy.”

After a fire in 1910 burned more than 3 million acres across Montana, Idaho and Washington—the single largest wildfire in American history—the nation and the nascent Forest Service pursued a strategy of total suppression of wildfires. The agency eventually implemented the “10 a.m. rule,” in which all wildfires were to be extinguished by the morning after they were sighted.

The zero-tolerance policy meant the nation put out the vast majority of blazes on first response. But it also eliminated nature’s gardening crew, and decades later, many forests held 10, 20 or 40 times more trees and other vegetation than they had a century ago.

Those overgrown forests are now fueling many of the nation’s most catastrophic blazes. Over recent decades, agencies have worked with local communities and Indigenous groups to reintroduce fire to ecosystems by letting certain wildfires burn or intentionally setting prescribed or cultural burns to reduce hazardous fuels and improve the health of the landscape. However, land management agencies still put out 98 percent of wildfires before they grow larger than 100 acres, according to the Forest Service.

The country’s troubled history with fire suppression is why so many land managers and firefighters are worried about the Trump administration’s approach and reacted so strongly to the president’s leaked April executive order referencing “the immediate suppressing of fires.”

The October report from Megafire Action that praised the potential of a U.S. Wildland Fire Service also stressed that it must strengthen capacity for good land management, “ensuring suppression does not crowd out long-term risk reduction work.”

The lesson the country should learn from the past century is that eliminating fire from the landscape is an “illusion,” Ingalsbee said. If the U.S. is “framing it as a war on wildfire, well, we’re losing.”

Another big way that human actions are fueling fire is the impact of climate change. Over the past two decades, as mounting greenhouse gas pollution distorts natural systems, extreme wildfires have become more severe and twice as common around the world, research published in 2024 shows. High temperatures—especially at night—and longer droughts are drying vegetation into easily ignited tinder, NASA warns.

Rather than combating climate change, the Trump administration is fighting efforts to address it: dismantling rules to reduce greenhouse gas pollution, incentivizing more fossil-fuel production, undermining renewable energy, yanking grants for disaster resilience work, suing states to block their climate superfund laws.

Recent executive orders dealing with wildfire ignore climate change, and the administration is wiping references to it from federal policies, websites and research.

All of that will affect firefighting efforts now and for years to come, experts say. The snuffing of climate science, for instance, means the new national wildland firefighting agency will effectively be blind to the impacts of global warming on the infernos its people confront.

Researchers, both in the government and at universities, are key to learning how fire behavior is changing and the best strategies to combat it. But multiple scientists told Inside Climate News that they have had to spend hours reworking grant proposals to remove language related to climate change, as well as mentions of diversity, equity or inclusion. This has taken time and resources away from doing the actual research, they said.

The Interior Department’s draft budget calls climate change research a “social agenda” and said the agency would eliminate funding to certain related programs to “focus on higher priority energy and minerals activities.”

What’s not in the agency’s control is how climate threats will shape the future of fire. If it launches as planned, the U.S. Wildland Fire Service will face that future, ready or not.

Inside Climate News reporter Wyatt Myskow contributed to this article.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,