In six generations, Jake Christian’s family had never seen a fire like the one that blazed toward his ranch near Buffalo, Wyoming, late in the summer of 2024. Its flames towered a dozen feet in the air, consuming grassland at a terrifying speed and jumping a four-lane highway on its race northward.

As the fire raged, Christian sped his truck to his house on the plains where his great-great-grandfather began homesteading in 1884. Earlier that day, he had been working to contain the blaze he was now scrambling to catch, and he hoped that his wife, Sara, had managed to evacuate herself, their children and some of their animals.

When he finally crested a hill overlooking his ranch, all Christian could remember seeing was scorched earth and fire.

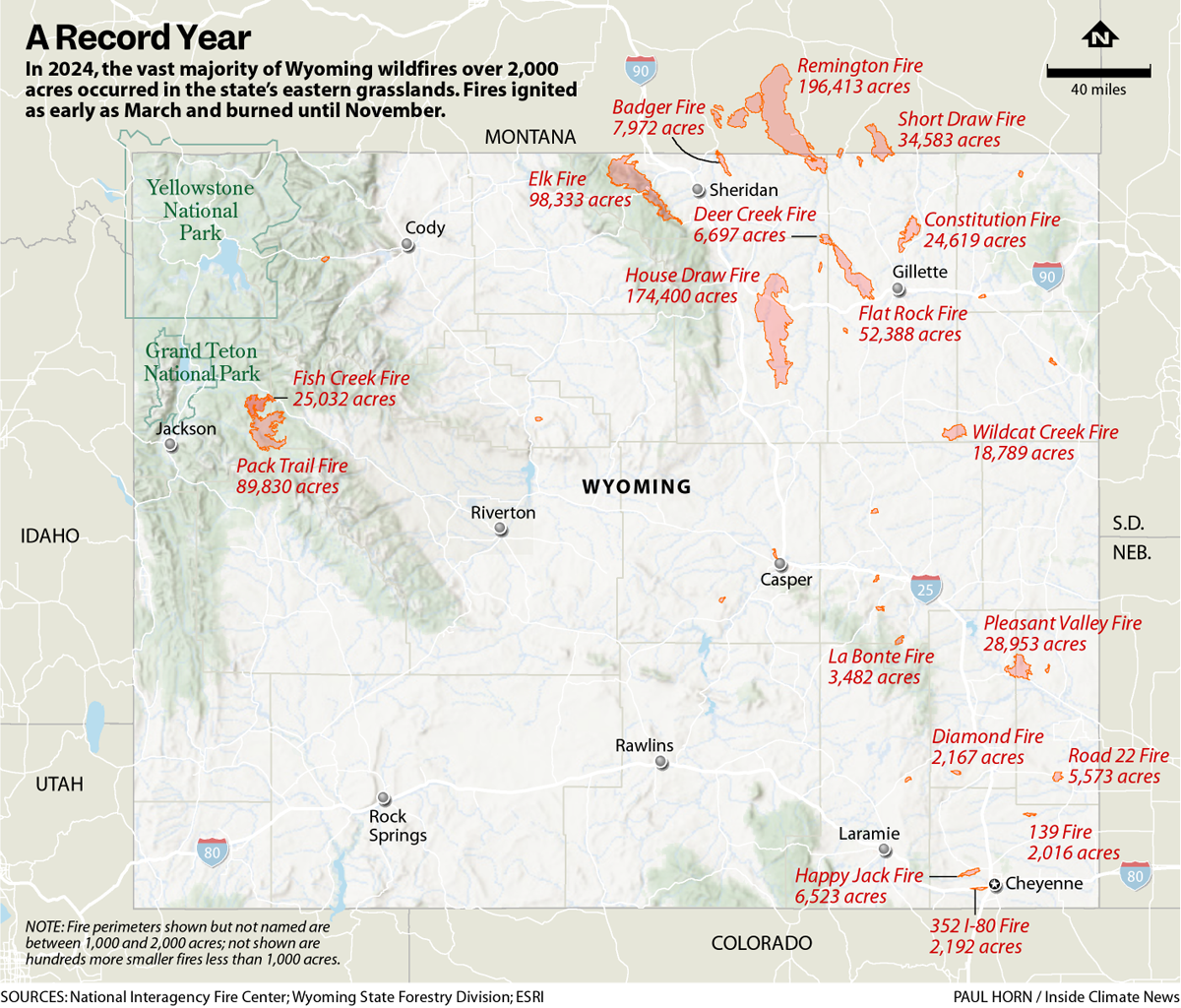

The fire threatening the Christian ranch would become known as the House Draw Fire, which grew into the largest blaze ever within Wyoming’s borders. In terms of acreage burned, 2024 was the second-largest wildfire season in Wyoming’s history, trailing only 1988, the year of the famous Yellowstone fires. By the end of 2024, Wyoming had amassed the fifth-most acres burned of any state, according to state data and estimates. Of the 32 fires that grew larger than 1,000 acres, almost half—including the three largest—burned in Wyoming’s northeast grasslands, predominantly on state and private land.

Miraculously, the blazes didn’t kill anybody, but hundreds of Wyomingites evacuated their homes.

Last year’s fire season was less intense, but still above average in terms of acres burned. As legislators prepare to convene in Cheyenne next month for a legislative session, the pall of the 2024 wildfire season has spurred many constituencies across the state to ask for more funding to combat or prevent enormous blazes.

And there are flickers of enthusiasm in the state legislature for changing how Wyoming fights fires, even as the ultra-conservative, climate change-denying Freedom Caucus wants to cut state spending. Gov. Mark Gordon and other lawmakers are taking calls from wildland firefighters for more resources seriously, but so far, state leaders’ proposed changes have not fully met counties’ proposals.

Wyoming’s recent fires are part of a West-wide trend of larger and more destructive wildfires that fire scientists warn is almost certain to continue increasing as humanity continues burning fossil fuels and warming the planet.

Wyoming has seen “this massive increase in the number of fires,” said Bryan Shuman, a paleoclimatology professor at the University of Wyoming, who studies the history of fire in the Rockies. “A big part of it is because the fire season is longer.”

Already, 2024’s wildfire season appears destined to loom over Wyoming for generations, even as some of the grasslands that burned that year show few signs today of being scorched.

Surrounded by Flames

Christian likely saw the lightning bolt that sparked the House Draw fire. Looking south from his property that morning, he saw lightning strikes peppering the black horizon. Soon, his pager trilled, calling him to a fire.

“The minute the pager went off, I knew exactly where I was headed,” he said. Christian has volunteered for Johnson County Fire Control as a firefighter for 12 years, as many ranchers do across the rural West, and he’s responded to such calls since he was a kid.

On the fire, his crew heard over the radios that the inferno had hopscotched the interstate and was headed north (flaming grasshoppers may have aided its charge).

Christian had run out of water to fight the fire by the time he learned the fire was headed toward his property. The department chief gave Christian water and told him to fight the fire at his home. He was relieved by that act of kindness for only a few minutes.

“Shit. Everything’s on fire,” he thought as he approached his property, which includes his parents’ home.

Christian’s ranch sits at the base of a bowl of grass in the prairies that roll up east of the Big Horn Mountains. A creek curves around the back of his home and barn. His neighbors were there fighting the blaze after being called by his wife, who had evacuated with their three kids and some of their horses.

The fire had been devouring the land. Cottonwoods by the creek perished, as did a tree Christian’s grandfather tended as a young man; the propane tank on his father’s property caught fire; embers ignited firewood under a mobile trailer that melted into rivulets of aluminum; 300 bales of hay burned for a week, Christian said, leaving a scar still visible nearly a year later (his grass was insured). Somewhere on the ranch, 100 cattle yearlings were trying to escape with their lives.

The neighbors brought water and struggled to connect the creek and the road into a fire line that circled the Christians’ home, barn and garage, dousing flames that threatened to cross the perimeter. But after several hours, the flames were still threatening to jump the line and the fire front was advancing. Just when it appeared the blaze was poised to consume the house, a plane appeared overhead to shower it in a plume of bright-red fire retardant to hold back the flames long enough for the neighbors to regroup and secure the perimeter.

Christian made it home just after the slurry drop that helped save the house, but the grasslands were still on fire. The flames were sneaking over the bridge spanning the creek, its slats slowly igniting one by one. He sprinted to the crossing and began flipping planks into the water before they could ignite. As it got darker, the light from the fires shone so brightly that Christian felt like he had suddenly been dropped into the middle of a city. Some of the most unwieldy 2024 fires in Wyoming ripped at night, which is typically when fire behavior calms.

When the conflagration had finally exhausted all its available fuel, Christian and his neighbors found themselves standing on an island in a sea of black. Without his neighbors’ efforts, Christian’s family almost certainly would have lost its home.

Ironically, the scorched earth is what made Christian feel like he could get a few hours of sleep that night. “Everything that could have burned was burned,” he said. In total, 9,000 acres of the Christians’ land had been scorched, accounting for about five percent of what burned in the 174,547-acre wildfire.

Muddy Past Hints at Smokey Future

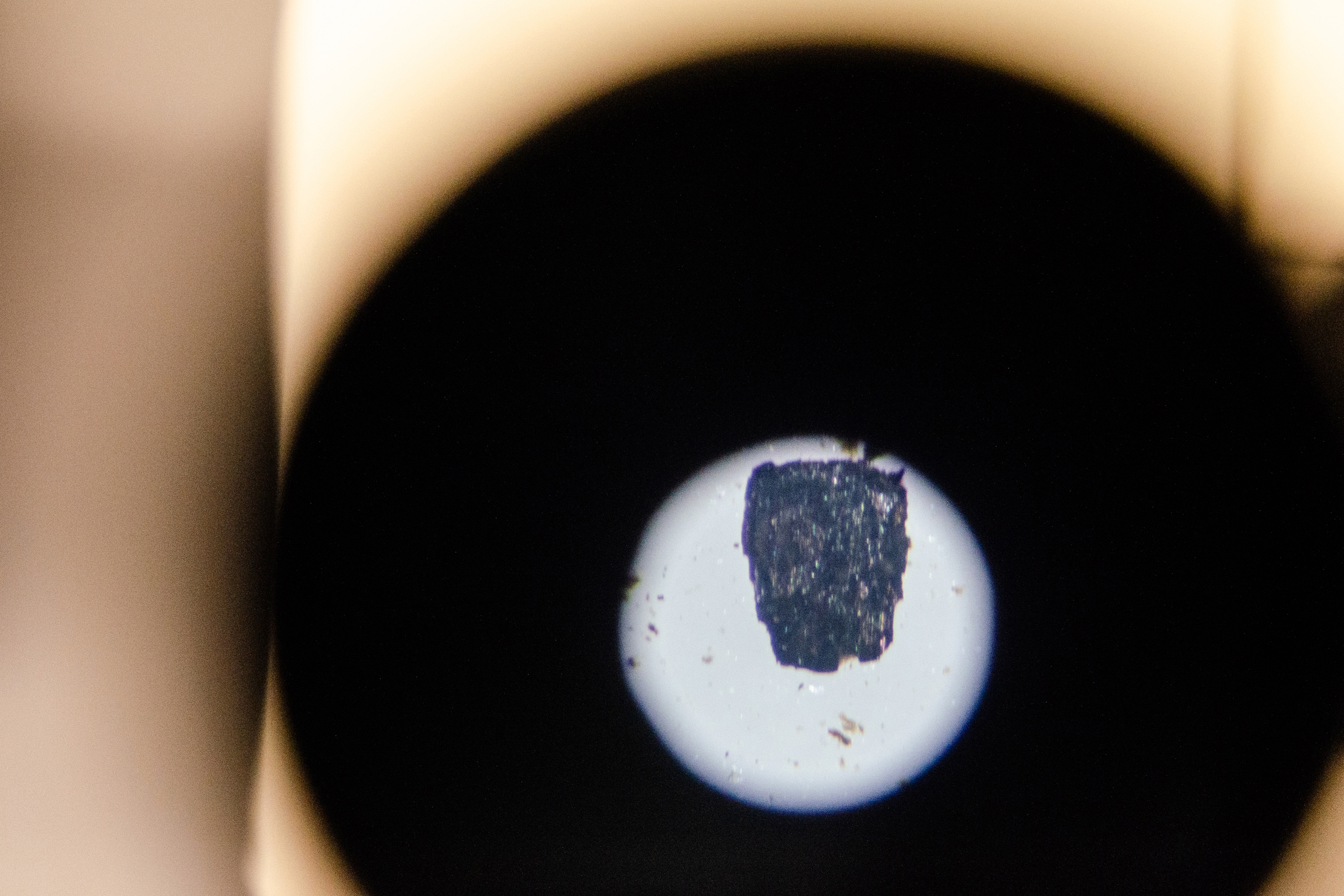

Nearly a year after the House Draw Fire, Bryan Shuman at the University of Wyoming was in his office delicately handling a three-foot-long plastic pipe filled with mud from the bottom of an alpine lake. “This is the history of the environment that we’re leaving behind,” Shuman said.

Over thousands of years, sediment layers in alpine lakes accumulated on top of one another, trapping charcoal from fires, which, when paired with tree ring records, microbial concentrations and trapped midgefly carcasses, creates a climate report from the ancient past. From this record, Shuman has concluded that large fires are burning more frequently in southern Wyoming and northern Colorado today than at any time in the last few thousand years.

“If you took a point on the landscape and said, ‘how often will this point get burned?’ on average, that point might, for most of the last 2,000 years, have only gotten burned once every 250 years,” Shuman said. “But now, we’re at the point where that one point might get burned every 60 years.”

Driving from Laramie into the nearby Medicine Bow mountains to check some of his mud core sampling stations in late June, lush vegetation bordered the road, but the burn scars from past fire seasons stood out, particularly those from 2020. Megafires plagued southern Wyoming and northern Colorado that year, including the three largest wildfires on record in Colorado, and another that spanned the border between the two states, leading Shuman to wonder if the huge fires his research predicted were already at his doorstep.

“I used to think these big fires are somewhere off in the future, but it’s already happening here. I thought it would take decades” he said.

In 2021, he co-authored a paper showing how large fires in the southern Rockies were beginning to occur more frequently.

“And that’s only going to get worse,” he said.

Shuman’s research has also taken him to the Northern Rockies, home to some of the country’s most iconic landscapes.

Scientists used to think the forests around Yellowstone National Park wouldn’t see more frequent wildfires; the cooler temperatures and snowpack that came with their northerly latitude would keep them relatively moister than forests farther south. But in 2016, fires in Yellowstone reburned areas that had been scorched in 1988 and 2000, signaling a possible shortening of the fire-return interval.

“We’re seeing the signs,” said Monica Turner, an ecology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who has studied fire in Yellowstone for decades. “It can happen. We shouldn’t think it can’t.”

The West’s megadrought has left trees, other vegetation and soils drier. Every uptick in drying exponentially increases the risk of a large fire, Turner said. In 2011, she co-authored a paper that predicted the time that it takes for areas of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem to burn could shrink from between 100 and 300 years to less than 30 under an extremely dry, high-emissions future, and years without large fires could become increasingly rare.

“I used to think these big fires are somewhere off in the future, but it’s already happening here. I thought it would take decades.”

— Bryan Shuman, University of Wyoming

Climate change is “adding gasoline to the flames,” she said.

Trees are adaptive, but if they experience fire too frequently, they may not have enough time to adjust. Some of Turner’s research has shown that by 2100, if humanity does not curtail its emissions, up to 50 percent of some forest area around Yellowstone could fail to regenerate after being barraged by too many fires too quickly.

Instead of storing carbon, Yellowstone would become a net source of carbon emissions.

“Fires faithfully track climate,” said Cathy Whitlock, a paleoecologist and researcher at Montana State. Whitlock, like Shuman, has used mud cores to study past behavior of fire in the Northern Rockies. She’s learned that the term “fire cycle” isn’t quite accurate, she said, because the climate is dynamic. “When it’s warmer, there are a lot more fires, and when it’s cooler, there are fewer fires.”

For humanity to avoid a future in which enormous, destructive fires occur multiple times in a generation, it must “reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels,” Whitlock said. “We need to flatten the temperature curve.”

Cheyenne’s Move

Fires were still making forests red in Wyoming when the U.S. elections made the nation’s most conservative state even redder politically. The “Freedom Caucus” of Wyoming Republicans gained control of key positions in the state legislature and further limited Wyoming’s already small-government approach to running the state by cutting property taxes 25 percent.

These taxes help fund Wyoming’s local fire districts.

In June, Shad Cooper and J.R. Fox, both county fire wardens, and Kelly Norris, head of Wyoming State Forestry, appeared in front of the Appropriations Committee to discuss the 2024 wildfire season. Four of the committee’s 11 lawmakers, all members of the Freedom Caucus, wore red blazers to highlight projections that Wyoming’s budget would be running a deficit within a few years.

It was the trio’s first opportunity to speak publicly with lawmakers about the fiscal commitments Wyoming needed to make to better manage fire in a warming world. Their testimony was sobering. Wyoming’s Emergency Fire Suppression Account, which helps counties cover the cost of fighting fire, had hovered around $100,000 after its inception in 1986, but has skyrocketed to over $52 million since 2003. The state’s limited human resources were also stretched thin: Despite managing over 32 million acres of land, the Wyoming State Forestry Division is among the lowest-staffed forestry agencies in the West, and the department routinely loses personnel to federal agencies with better pay and benefits, Norris said. Nearly 90 percent of fire departments in Wyoming are staffed with volunteers who are having to respond to more and longer-duration fires. The dangerous working conditions and long hours are increasingly having a negative impact on the firefighters’ families and social lives.

“This is not sustainable, and it is a major red flag,” said Norris, who has promised her family she would never again commit as much time to fighting fires as she did in 2024.

A third of volunteer firefighters in Wyoming are over 50, and Cooper noted fewer young people have been volunteering in the last five years. “That reduction scares me, and I think it should scare everyone in the state of Wyoming,” he said. Without younger personnel, he said Wyoming would “have more large wildland fires because they escape and we’re not able to keep them small.”

Wyoming has another source of low-cost firefighting in addition to its volunteer departments. The state relies extensively on an inmate crew to fight wildfires for “a couple bucks an hour,” Fox said, and lawmakers expressed enthusiasm for expanding that program. Norris wouldn’t disclose inmates’ salary when asked by Inside Climate News, but said Wyoming more than doubled their pay, and it is currently more than $2 an hour.

Even if that program were to grow, it can’t keep up with the forecasted increase in wildfire in the state.

Learn More

Click on the following link to access county wildfire protection plans in Wyoming, and learn how to make your home more fire-resilient.

Cooper and Fox requested the state appropriate funds to its forestry department to hire 14 full-time employees with competitive pay and benefits for wildfire suppression, and an additional 40 seasonal firefighters, at a total cost of about $5.5 million every other year.

The state’s Emergency Fire Suppression Account should be funded at a minimum of $40 million annually, Cooper and Fox told the committee, with at least $60 million available for a worst-case scenario year. The duo also suggested lawmakers create a $10 million “fire mitigation account” to help pay for reducing hazardous fuels on state and private lands, a more cost–effective way of preventing enormous blazes.

“We should look at some opportunities to be more proactive,” Fox said. “This meeting is an opportunity for change.”

Carli Kierstead, the founder and director of The Nature Conservancy’s Wyoming forest program, attended the June appropriations meetings and was glad to see forward-looking proposals, but anticipated that, with the Freedom Caucus intent on cutting spending, they would be subject to negotiations.

Fire season is getting “extremely expensive, and we can’t just go about with business as usual,” she said. “We have to make additional investments, even if we are a fiscally conservative state, because it’s worth it in the long run.”

Chiefs of other paid and volunteer firefighter departments are looking to Wyoming to figure out how to maintain or increase funding for wildfire mitigation and suppression, regardless of what happens with taxes in the state.

“We need to do a little more with financing,” said Lisa Evers, chief of the Casper Mountain Fire District. Evers, a Casper native, has run the volunteer department on Casper Mountain for the last six years. “[Legislators] cut the property taxes by 25 percent, which, yay, because that means less I have to pay,” she said. But less money also affects how her department covers fuel and equipment costs, which have “gone up astronomically,” she said.

“We’re no different than insurance,” said Brian Oliver, chief of the Natrona County Fire District, also based in Casper. “You might pay your premiums for 25 years and never use it, but the one time you need it, you gotta have that.”

The departments are neighbors, but Oliver’s 20-person team is paid through local property taxes, while Evers’ team is made up entirely of volunteers. While Oliver is appreciative of the support the state has provided in the past, like funding new aviation resources, Wyoming lawmakers “really decreased our annual budget quite a bit” by cutting property taxes, he said. “That hurts.”

Last summer, members of the joint appropriations committee mostly expressed awe and gratitude for firefighters during several presentations on the rising costs of wildfires. And at a committee meeting on Halloween, lawmakers appeared open to easing their budget-cutting zeal.

“I would consider myself a fiscal hawk, and yet we see this as a necessity that we begin to go in a different direction,” said Rep. John Bear, the Freedom Caucus’ chair, whose district lies just outside Gillette. “We may not all leave these meetings completely pleased with the outcome, but we will take the state in a direction that we think addresses the risk that we see.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowIn December, the joint appropriations committee published four bills that would allow State Forestry to hire more full-time and part-time firefighters and improve benefits and pay for fire personnel. The bills will be some of the few pieces of legislation that receive attention during next year’s compressed legislative session, where lawmakers devote most of their time to drafting the state’s budget.

“I don’t know where we’re going to land,” Norris said. “But I’m hopeful.”

In his budget proposal, Gov. Gordon acknowledged that fires in Wyoming were growing larger and more challenging, and praised the volunteers who fight them. Still, he did not create a fuels mitigation account, and proposed adding fewer new personnel to state forestry than the county wardens had requested. His budget would keep the state’s emergency fire suppression account at $30 million.

Cleaning House

Getting Wyomingites to invest in making their properties more flame resistant and accept the inconveniences that accompany reducing the fire risks around them may prove more difficult than convincing the state’s conservative government to fund fire fighting and fire mitigation.

“The hardest thing in our line of work is human free will,” said Oliver at the Natrona County Fire District. “You can show as many PowerPoints as you want, as many pictures as you want. You can talk about the goriest, nastiest stories that you want. But everybody has the mindset that ‘It’ll never happen to me’ … until it does. And then, once it does happen to them … they get very proactive afterwards. And I hate to see it, but it is very true.”

Evers, Oliver’s counterpart on Casper Mountain, put it a little more bluntly: “A catastrophic fire, it usually lights a little fire under people,” she said last summer outside her station on top of the mountain. Evers and Bryan Anderson, Wyoming State Forestry’s District 2 director, were discussing the difficulty of fostering a fire-adapted mindset in homeowners.

“Everybody has the mindset that ‘It’ll never happen to me’ … until it does.”

— Brian Oliver, Natrona County Fire District

After two fires six years apart consumed much of the forest on the east and west sides of Casper Mountain, but left the middle—where most of the structures are—virtually unburned, “more people [were] out doing mitigation, removing deadfall, calling about stuff and asking the questions,” Evers recalled.

“We’d hold a field day for landowners up here. They would show up,” Anderson agreed. Peak attendance for fire prevention and awareness workshops was between 30 and 40 people, Evers said, less than 10 percent of Casper Mountain’s population, but still a healthy showing. “Last time we tried to hold [a field day] here … I think 12 people showed up,” he said, lamenting the decline in interest.

This month, Evers plans to meet with the National Fallen Firefighter Foundation to discuss hosting a two-day education program in Casper this June that would explain the virtues of home hardening and creating defensible spaces, and teach homeowners the risks firefighters face when communities that are not fire adapted burn.

She believes the foundation will tell residents “if you don’t do this, firefighters will die.”

“Time for the tough love,” she said.

When a homeowner does get the message, the results can be transformative.

“Nuked”

In 2012, Gary Berchenbriter lost his cabin on the east side of Casper Mountain to the Sheepherder Hill fire. Anderson and other firefighters had fought hard to save the home—because they felt safe; the Berchenbriters had what firefighters call “defensible space” around the structure and a nearby grove of aspens, a deciduous tree that retains more moisture and doesn’t ignite as easily as conifers.

But upon returning home, Berchenbriter described his land as “just nuked.”

The family decided they wanted to rebuild, and did so to be more resilient to wildfires. Their new home uses earthen plaster siding and has a metal roof, both of which are considered safer than wood and asphalt. The home’s centerpiece is a scorched ponderosa pine tree that used to sit in the front yard but now reaches from the floor to the ceiling inside the house, its black scars a reminder for the family.

While Berchenbriter’s immediate neighbor is an excellent land steward, many other Casper Mountain residents are second-home owners, and Berchenbriter said he was not sure how well the community is prepared for a fire that strikes the middle of the peak. “Generally, the farther away you are, the less interest you have in [fire protection],” he said. “The people that live on the mountain I think are very aware and take care of it.”

Homes up narrow canyons and in overgrown, drought-stressed forests accessible by only a single winding road are littered across Wyoming and the West. Often “dream homes,” they are increasingly a nightmare to insure. Requirements for home hardening, tree thinning and vegetation management are usually implemented at the county level, and consistency between how homeowners manage their fire risk is not guaranteed.

“At what point do you roll up the newspaper and spank the public?” said Jacob McCarthy, State Forestry’s District 5 forester covering Johnson, Sheridan and Campbell counties. “Are you going to comprehend what is being told to you? Or are you going to have the mentality of it’s not going to happen to me, or it doesn’t matter because I have insurance and they’ll pay for it?”

Jacob McCarthy, who spent weeks fighting fires in northeastern Wyoming during the summer of 2024, wants more people to understand that fire is a natural process Wyomingites must learn to live with. Credits: Jake Bolster/Inside Climate News and Jacob McCarthy

McCarthy delivered this tough love as he drove through Story, Wyoming, a small community on the rim of the Big Horn Mountains, to a patch of state land he hoped would one day be treated with a prescribed burn. Tribes across the U.S. have used intentionally set fires, known among Indigenous practitioners as cultural burns, for centuries, far longer than the state of Wyoming has existed. Only recently has federal and state fire management grown to include prescribed burns.

In 2024, a fire ripped through 98,000 acres on the east side of the mountain, and McCarthy hoped a burn intentionally set in the area could head off a similar conflagration.

“This landscape has seen fire for thousands of years,” he said. “What we’ve done is we’ve taken that fire off the landscape. Doing that, we’ve painted ourselves into a corner … We basically fired the maid, and we didn’t start cleaning our own house.”

Spark Plugs

Fighting fire with fire is risky. Even the slightest change in weather conditions can blow a prescribed fire burning slow and low on the ground into an inferno that escapes to threaten lives and property. Much more often, any one of a dozen conditions like wind, heat or fuel moisture fall outside the prescribed safe ranges, leading burns to be shut down. Permitting and staffing the burns requires coordination between federal, state and local governments, and buy-in from nearby communities that will be affected by the smoke, even if the burn goes well, and possibly flames if it does not.

Given all the liability, it is unlikely to ever become a tool Wyoming can wield without help, despite research showing low-intensity prescribed burns could prevent megafires in vast areas of forested land across the state.

As a state agency, “we don’t have the resources to prep and implement a prescribed fire,” McCarthy said.

Even a successful prescribed burn can generate a lot of controversy.

“The big issue really is—besides escape—smoke, especially for long-duration burns,” said Andy Norman, a retired fuels specialist with the Forest Service based in Jackson, Wyoming, who estimated he has participated in more than 100 prescribed burns. “The Forest Service definitely had to do some outreach, making sure that people understood that this is a short-term impact, that long-term, there will be less chance of a wildfire in this area.”

In 2022, Liz Davy, a former Forest Service district ranger disillusioned by the lack of public acceptance for proactive fire management in the Yellowstone ecosystem, co-founded the Greater Yellowstone Fire Action Network, one of many nonprofits dedicated to helping communities live with fire in the region.

The network distributes air filters during smoke events, hosts webinars on home hardening and defensible spaces and has also helped counties around Yellowstone, including Lincoln and Sublette, create “smoke-ready” communities, where residents are trained to keep each other safe from the emissions of wildfires or prescribed burns.

One aspect of their model relies on finding a neighborhood ambassador, a community member who can serve as an example of how to live with fire. “We call them ‘spark plugs,’ those people who are really passionate about [fire],” Davy explained on an August trip to the Caribou-Targhee National Forest, where she was a ranger. She was on her way to observe work being done by a fuels crew—professionals trained to reduce a landscape’s fire risks by thinning forests and, when appropriate, conducting prescribed burns—which her organization had helped plan.

A group of mostly young women clad in thick chaps and carrying chainsaws waited for Davy on the side of the road. She seemed eager to throw on fire-resistant Nomex pants and join the team.

The Nature Conservancy crew is certified to thin vegetation and conduct prescribed burns anywhere in the country. Their work supplements federal and state fuels treatments, and this job would help the Forest Service to improve its fire breaks and promote aspen regeneration.

Despite mostly camping on the job for a couple weeks of, on average, 10-hour workdays, few of them showed fatigue. Several said they were grateful they got to do work they feel helps communities get ahead of disasters.

“I just wanted to do prescribed fire as a job,” said Christian Craft, the group’s leader and a former Forest Service firefighter. “I just think it’s a lot more important to be proactive than reactive when it comes to this.”

Craft is pursuing his burn boss certification to plan and execute prescribed fires, and thinks he’ll earn that more quickly through The Nature Conservancy than the Forest Service.

The crew got their chainsaws humming, and soon, trees were crashing across the forest. Davy left with a smile on her face. After years of working in a male-dominated profession, she was heartened to see so many young women working in fire.

“How are we going to change the culture of people who live in a fire-dependent ecosystem? One person at a time,” she said. “Eventually … it snowballs. You’ll get states involved, you’ll get lawmakers involved, you’ll get county commissioners involved … it’s really one person at a time.”

Is climate change leaving enough time for that? “Not always, no,” she admitted. “It’s taking a long time.”

A Cold Day in Hell

Last July, nearly a year after the House Draw Fire, Jake Christian, the Buffalo-area rancher, left his home, still speckled orange from the slurry that saved it, and drove around his property. Yellow grass had sprouted so densely that it was hard to see anything had burned.

Christian and his father spent the year after the fire rebuilding $1 million of burned fencing using fire-resistant metal. “It’ll be a cold day in hell when I put another piece of wood in the ground,” he said. He’s also considering adopting virtual fencing—GPS collars that make noise then shock a cow if it strays into electronically cordoned-off areas. He plans to attend a symposium on virtual fencing this winter, and if he decides that the technology could work for him, it may one day allow him to dismantle much, if not all, of his fenceline.

Though all their yearlings survived, the Christians had to sell about 80 after so much of the grazing land surrounding their home burned. Selling so many cattle was devastating, particularly for his wife, Sara.

“Right now I think of my life as before the fire and then after the fire,” she said.

Cottonwoods along the stream behind the Christians’ home showed no signs of new growth, and Christian was devastated to lose other trees, like the one his grandfather tended.

“It was so beautiful before,” he said as his truck rumbled past black tree trunk. “Seeing them all gone, I mean, there are so many of them … how do you replace a 100- or 200-year-old tree?”

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Bryan Shuman’s title.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,