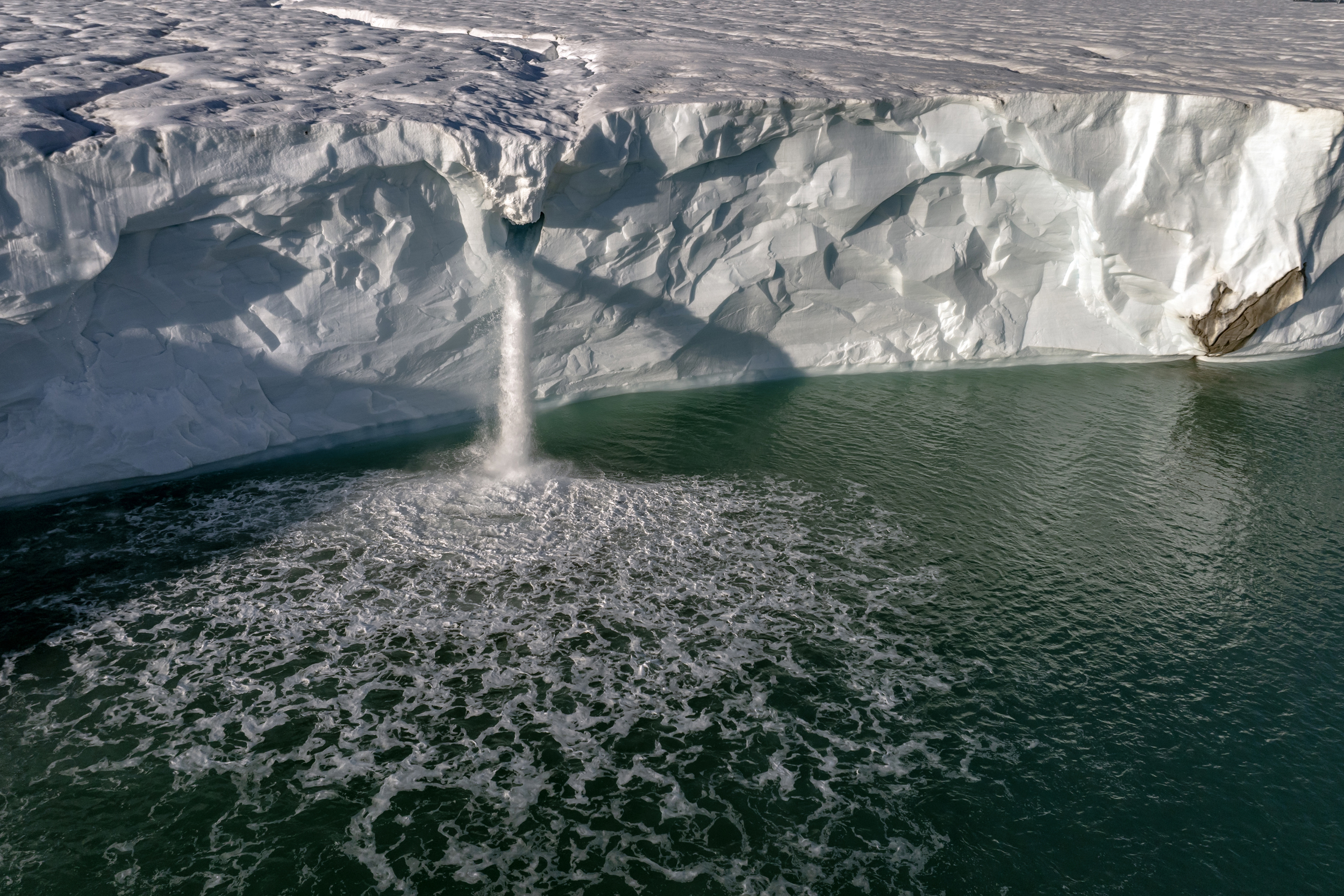

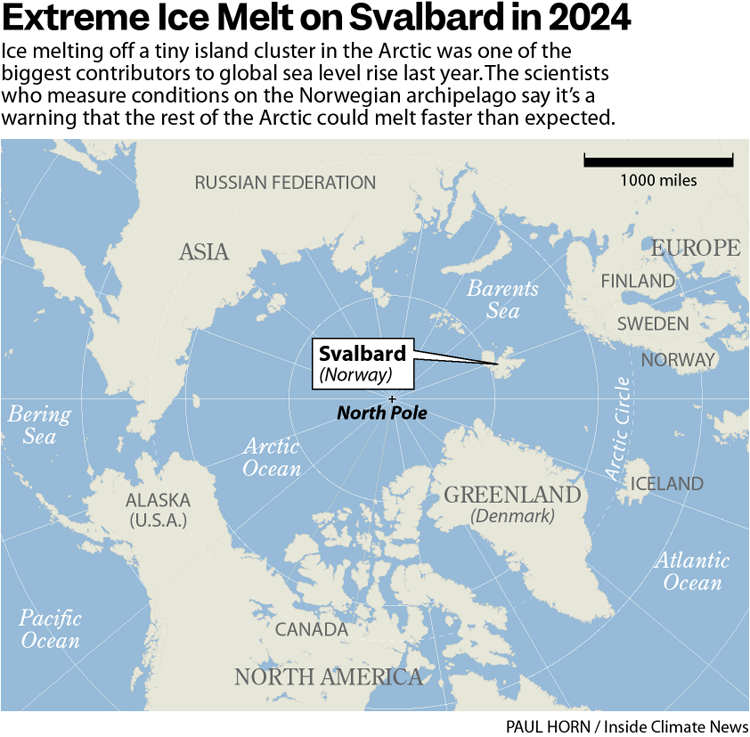

A new study released this week presents the record ice melt on the Svalbard islands in summer 2024 as a glimpse into a future where other Arctic ice masses, including those on Greenland, could melt faster than currently anticipated.

The amount of ice that melted on Svalbard, the archipelago north of Norway in the Barents Sea, made the region one of the most significant contributors to global sea level rise last year.

Ice melt records set in 2020 and 2022 were just marginally greater than previous years, but an extreme and long Arctic heat wave last summer, intensified by weather patterns disrupted by climate change, opened a new page in the record books. The melting was “in a different league,” said Thomas Vikhamar Schuler, professor of geosciences at the University of Oslo and lead author of the research published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Schuler said the study shows how what seems like a once-in-1,000 year event “will become normal in the future,” he said. “Usually, we say, ’Oh, let’s talk about the world that our grandkids will experience.’ But this is something within our lifetime.”

The new data measuring the loss of ice confirmed some of scientists’ worst fears about global warming, said James Kirkham, an ice researcher with the British Antarctic Survey who did not contribute to the new study.

“I think all glaciologists felt a sense of trepidation when we saw the images coming out of Svalbard last summer,” he said. “But the official numbers are truly appalling.”

The scale and speed of ice loss on Svalbard “underlines a sobering reality for the broader climate system,” Kirkham said.

Most of the 2024 glacier melt occurred during six weeks of record-high temperatures driven by a persistent pattern of winds and pressure systems in the atmosphere. The pattern is conducive to summer extremes like heatwaves and droughts, and has been happening more often in recent decades in the human-warmed climate, according to recent research by Michael Mann, a University of Pennsylvania climate researcher, and others.

The new paper warns that “Svalbard’s summer of 2024 serves as a forecast for future glacier meltdown in the Arctic, offering a glimpse into conditions 70 years ahead,” the authors wrote.

The potential consequences of the rapid glacial melt around the world include more mountain flash floods, and the potential for severe water shortages as glacier-fed rivers dwindle.

The sudden influx of fresh water from the islands to the surrounding sea likely also had an impact on marine ecosystems, starting at the base of the food chain with plankton, which is very sensitive to water temperature and salinity. Up the food chain, migration and breeding patterns for marine mammals and seabirds are closely linked with plankton cycles, and a disruption can starve an entire generation of breeding birds.

Research has also linked surges of fresh water into the North Atlantic with extreme weather in Europe, and potentially North America. And in a worst-case climate scenario, cold, fresh water from Svalbard and other parts of the Arctic is probably also contributing to the weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, a key ocean current that carries warm water toward northwestern Europe. A breakdown of the current would cause extreme climate impacts in Europe.

The outlook for Svalbard’s ice is grim even in the rosiest climate scenario outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Schuler said. The IPCC is a global scientific body that issues regular comprehensive climate reports, including the best available projections for future human-caused warming and its impacts.

Even if the world’s countries reach their medium-term goal of cutting emissions to zero by 2050, many Svalbard summers toward the end of the century will be like last year’s, he said.

Correction: The graphic in this story was updated Aug. 23, 2025, to correct a reference to Greenland.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,