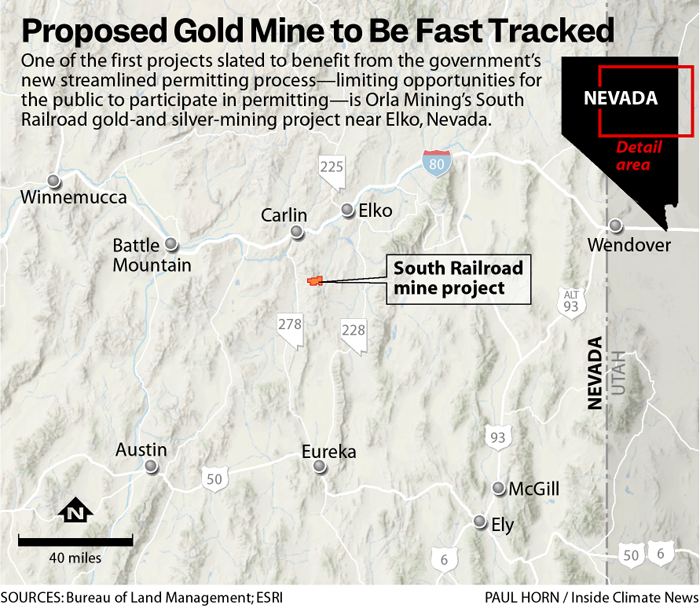

A proposed gold and silver mine in northern Nevada is slated to be the first open-pit mine to go through accelerated permitting from the Bureau of Land Management, which provides far less opportunity for the public to engage with the process and help avert later problems.

The move follows the Trump administration’s actions this summer to roll back procedures in a foundational U.S. environmental law.

Under new guidance from the Department of the Interior about implementing the 55-year-old National Environmental Policy Act, opportunities for the public to participate in permitting will be severely limited. Now, public comment periods are only required when the initial notice of intent is published for a project, which skips the requirement for a draft environmental analysis. The streamlined process does not allow for public comment on a project’s environmental review before an agency approves the project.

One of the first projects slated to be permitted under the new NEPA guidance is Orla Mining’s South Railroad mining project near Elko, Nevada.

The mine may be the test case for other projects under the new accelerated permitting process. Experts and environmentalists fear the revised NEPA policies will gut the public’s ability to provide input on projects in their communities and have their concerns addressed before construction begins.

“When we cut out public review, we’re missing that ability for mines to be less damaging and more protective,” said Roger Flynn, director of a nonprofit law center called Western Mining Action Project and an adjunct professor at the University of Colorado School of Law. “It’s hard to do that with a massive open-pit mine with cyanide heap-leaching and large waste dumps, but you’re missing the opportunity for the public to say, ‘You can do this better.’”

Feedback from the public isn’t the only thing that would be lost, Flynn noted.

”Obviously, when you weaken the substantive environmental controls, you’re just putting public resources on the chopping block, whether it’s wildlife, our cultural and historical heritage, water quality—you name it, they’re going to be shortchanged,” he said.

Other projects have been fast-tracked this year, such as a uranium mine in southern Utah, but by using executive orders and emergency clauses to speed the process.

Under the new NEPA guidelines for the Bureau of Land Management, the South Railroad mine will only have public comment during the project’s public scoping period, the first initial step for any project needing federal approval, which comes before any in-depth environmental assessments occur.

There will be no draft environmental impact statement for the public to review and ask to be revised. And when the final EIS is published, the record of decision for the project will also be issued. So the public will have no chance to comment on the findings of that key review—which notes how a project is expected to affect the environment, including people nearby—before the BLM issues its decision.

Permitting reform has been a major talking point for both Democrats and Republicans for years. Project delays have been blamed on the requirements of laws like NEPA, but researchers have found a lack of staffing at permitting agencies, projects’ financing issues and community opposition and litigation—often in response to a lack of project transparency—are far more often the cause.

“What’s really interfered with the permitting and mining projects is a lack of transparency,” said John Hadder, director of Great Basin Resource Watch, who attended a public meeting in Elko for the South Railroad project. “Over the years, the ones that have really gotten delayed, largely because of litigation, is because they weren’t transparent. They weren’t clear. And so the public had no recourse but to file litigation. So that’s why, I think, this is not really addressing the core problem with the permitting process.”

Donald Dwyer, Orla Mining’s general manager, said in an email that “Nevada’s [BLM] process was designed to aide in a more efficient Notice of Intent to Record of Decision timeline through more rigorous frontloading of environmental baseline collection and analyses.”

“The new process is intended to bring transparency and efficiency without compromising the integrity of the environmental analyses,” he said. The new process “allows for better business planning,” he added, and he said the mine will benefit the local economy via new jobs, spending and taxes for local government.

“Many of our current team members have lived in northern Nevada for a number of years, so we want to ensure this project brings pride to our community,” he said. “Orla continues to keep the community engaged and updated through multiple avenues—email distribution lists, community meetings, and updates to local community groups.”

The BLM did not respond to requests for comment.

Limiting Public Participation to Speed Permitting

The proposed gold and silver mine has also been added to the federal government’s FAST-41 program as a transparency project, which are selected by the executive director of the federal Permitting Council to allow more public visibility into permit status, which in turn is supposed to lead to quicker and more predictable project approvals.

Opponents of the mine and the new NEPA guidelines don’t believe the reforms will increase transparency, let alone maintain the integrity of analysis, as Orla Mining contends.

“NEPA seems so arcane and bureaucratic and ‘oh, it’s red tape,’ but in reality, that red tape is the only thing standing between us and having our water poisoned and our air unbreathable and our wildlife all dead,” said Patrick Donnelly, the Great Basin director for the Center for Biological Diversity. He’s concerned about the South Railroad project’s potential to degrade water and habitat for the declining sage grouse and threatened Lahontan cutthroat trout found in the mine area.

“The mandated disclosure and analysis of the impacts to the environment of federal actions is how we ensure we have a clean environment,” he said. “So that’s about wildlife, but it’s also just about human health and the water we drink and the air we breathe. Public participation is an essential part of that. NEPA is about democracy and about bringing people into that process for accountability. These agencies need accountability, and if they are left to their own devices, they will do whatever the industry tells them to do.”

Tribal advocates expressed concern as well.

“This lack of review ignores critical impacts on water, animal life, cultural sites, and traditional gathering areas, including medicinal plants essential to community health,” said Fermina Stevens, executive director of the Western Shoshone Defense Project, in a statement. “The Department of the Interior and BLM continue to ignore the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discriminations’ 2006 decision, ‘to freeze, desist, and stop’ actions being taken against the Western Shoshone Peoples. The damage caused by this project and others will be irreversible, affecting not only current communities but also future generations who depend on these resources. Full NEPA compliance and active cultural monitoring are legally and ethically required before any mining activity occurs.”

“These agencies need accountability, and if they are left to their own devices, they will do whatever the industry tells them to do.”

— Patrick Donnelly, Center for Biological Diversity

The Trump administration’s revised NEPA policies come after recent Supreme Court decisions, like its Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County ruling earlier this year, which have limited the scope of environmental reviews, said Lindsay Dofelmier, counsel at Colorado law firm Davis Graham & Stubbs, who focuses on mining issues.

She said the revised NEPA regulations “wiped out” the guidelines from the Council on Environmental Quality, an office in the White House that consults and coordinates with federal agencies regarding NEPA permitting, that were the foundation for permitting management.

The previous CEQ regulations required public comment on both the Notice of Intent and draft Environmental Impact Statement, and mandated publication of a final EIS before an agency made a final decision on a project. The updated handbook just requires public comment during the initial Notice of Intent.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowBut it’s important to keep in mind that the handbook is not the rule of law, Dofelmier said, and until courts rule on lawsuits over fastracked permits, it’s unclear how the regulations will play out.

“It kind of condenses that public participation timeline, if you will, or it tries to,” she said. “Whether that’ll stand up to scrutiny is yet to be determined.”

New Jobs and New Threats to Species and Water

Orla’s proposed mine would extract gold and silver from a 8,548-acre project area, digging up more than 200 million tons of material, about 75 percent of which will be waste stored in three facilities, according to federal documents about the project’s plan. To access the metals, Orla plans to dig four open pits hundreds of feet deep, at least two of which will require dewatering, the process of removing water from the aquifer to reach the minerals.

The company estimates it will pump a maximum of 300 gallons per minute from at least nine wells into the aquifer. Water from the pits will be used for mine operations, which are expected to consume 390 to 450 gallons per minute.

The dewatering is expected to draw down the aquifer’s water levels by 10 feet in the area, according to BLM documents. Once the mining is complete, lakes will form at the bottom of the pits that will need to be monitored for water quality: They are expected to be acidic and have unsafe levels of arsenic, and will discharge into the local hydrographic basin.

Excess water will also be treated and then sent into Dixie Creek, which is a habitat for the endangered Lahontan cutthroat trout. The area is also home to multiple sage grouse leks, the mating grounds for the rapidly declining bird species.

Over the 16.5-year life of South Railroad, Orla Mining expects to recover 918,000 ounces of gold and just over 1 million ounces of silver. It plans to employ 300 to 600 people to construct the project and around 300 employees once mining commences.

The BLM, according to its Notice of Intent, expects to issue a record of decision in “winter 2025-2026.” Dwyer, with Orla Mining, said once the company receives its final permits, it anticipates a year and a half for construction before mining commences.

Donnely, with the Center for Biological Diversity, said that having less time to review the project and far less detailed information makes it harder for groups like his to submit informed comments. For example, the center would typically have a third-party hydrologist review the project’s water impacts using the data published.

“But if we’re not given any information, how are we going to verify that?” he asked.

And if a project is approved on what a watchdog group thinks is flawed science, but that criticism can’t be put on the record due to the limited opportunities to provide feedback on the project, then that feedback can’t be brought up in litigation later, he added.

Correction: A previous version of the caption that accompanied the photo in this story misidentified the area in the photo. The photo does not show the area where water from the mine would be discharged, but where one of the mine’s pits would be dug.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,