CLARKE COUNTY, Ala.—In the Land Between the Rivers, even the poison ivy tries to grow vertically.

Locked in a constant race against time and tides, the vine sends its notorious three-leaf clusters stretching upward like cypress knees, desperate to gain enough of a foothold to survive when the floods come back.

“It’s almost like a race for the sun when you’re not in the flood cycle,” said Mitch Reid, state director for The Nature Conservancy in Alabama. “It’s always a reminder of how dynamic these systems can be.”

For the poison ivy, it probably won’t work. The older, thicker trees that make the canopy overhead have visible waterline marks 10 feet or more off the ground. By March, this area will likely only be navigable by boat, the ivy flooded out or at least beaten back to the permanently dry land, far away from the fickle shorelines.

Still standing will be hundreds of trees—cypresses, oaks, sycamores, tupelos, willows and more—that have survived decades if not centuries of floods and established roots deep enough to keep standing and to hold the soil in place, even when it’s underwater.

And now that cycle will continue uninterrupted for the foreseeable future.

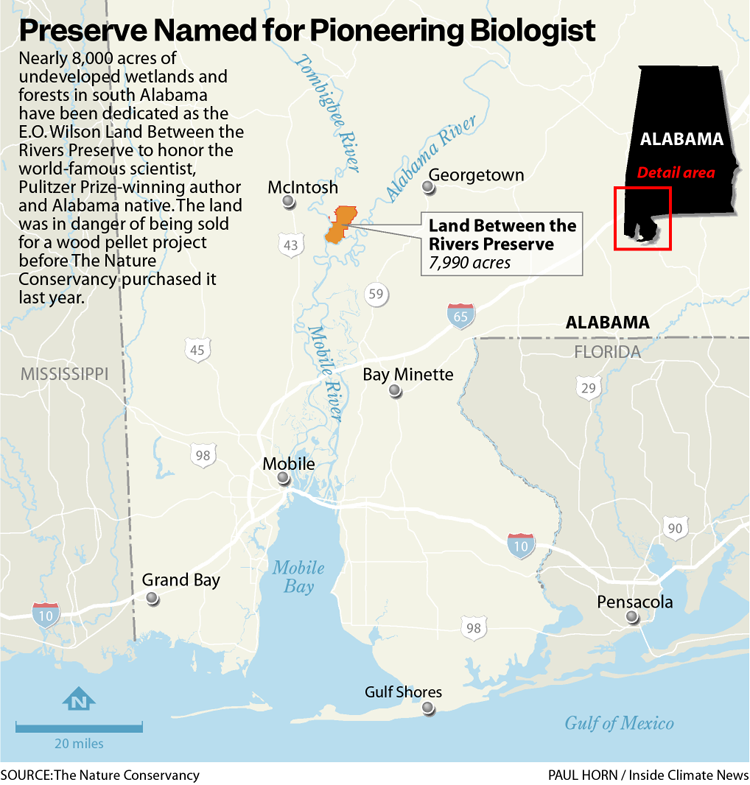

These deep mud soils, swamps and bogs are part of a new 8,000-acre tract now officially called the E.O. Wilson Land Between the Rivers Preserve, a sprawling expanse of undeveloped swamps, bogs, streams and forest in south Alabama.

The preserve includes the area in between the Tombigbee River, which carries the runoff from much of west Alabama and Mississippi, and the Alabama River, which takes its flow from central and east Alabama, Georgia and parts of Tennessee.

Those two massive rivers converge a few miles downstream, forming the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, one of the largest and wildest undeveloped areas east of the Mississippi.

Reid and colleagues from The Nature Conservancy took representatives of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and local donors to the preserve on a sunny Friday morning for a boat tour and hike around the new preserve.

“The birds are singing, we’re watching an osprey fly with us, fish are jumping out of the water,” Reid said after the trip. “You can hear the tree frogs over the boat engine. It just really felt like we were in old Alabama, a place that time forgot.”

TNC purchased the land for conservation in 2023 using funds donated by Patagonia’s Holdfast Collective and others, and has now named the preserve for Wilson, the famed author and scientist who won two Pulitzer Prizes for nonfiction and popularized the term and concept of biodiversity.

Wilson first developed his love of nature and understanding of natural systems as a boy exploring the Delta, and now an expansive swath of that undeveloped natural space bears his name.

Paula Ehrlich, president and CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, worked with Wilson for 15 years before his death in 2021, and said that Wilson would have jumped at the chance to preserve this land.

“This place was extraordinarily close to his heart,” Ehrlich said after visiting the preserve. “It’s the sort of place as a boy that transformed his relationship with nature and allowed him to imagine that he could make a difference in the world.”

In late September, the ground near the river’s edge is a thick crusted mud with deep cracks, reflecting the recent lack of rainfall. It’s mostly stable enough to support a person’s body weight, though it has a spongy feel that pushes back against the bottom of your boots as you walk.

Thick layers of branches, sticks and other river debris pile up between some of the tree trunks, deposited from somewhere upstream. Songbirds sing from the trees and herons, egrets and ospreys patrol the waters for their next meal.

“I always remembered what an extraordinarily peaceful place this is, like going into a spa,” Ehrlich said. “And to revisit that feeling in the spirit of thinking about Ed and what he would be thinking about this one, it’s really moving for me.”

The smaller trees are fairly close together, with four-inch golden-silk orb weavers and other spiders spinning webs in between them. The old giants are spaced much farther apart, making it an easy walk through their dappled shade.

And there are some massive old-growth trees on the preserve, some of the largest in Alabama. A bald cypress within the preserve is officially listed as the largest cypress tree in Alabama, according to the Alabama Forestry Commission, which compiles a list of “champion trees” using a score that includes the height, circumference, and crown spread of various native species. The cypress tree on the preserve also has the highest point score of any species, so it could be considered the largest tree in Alabama.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowKeith Tassin, deputy state director for the Nature Conservancy in Alabama, said a massive Nuttall oak that we visited on the journey was larger than the one officially listed in the record book, and will likely become the new state champion once the Forestry Commission validates the score. The current champion Nuttall oak is in a different part of the preserve.

“We saw how gigantic that Nuttall oak was, and you realize, if we let this system, and systems like this, thrive, what good they can do for us, from a carbon standpoint to holding the mud in place,” Reid said. “We stepped off the boat, and you could see deposits of mud centuries thick.”

Developing the land, or harvesting the massive hardwood stands there, would be difficult but not impossible. The new Wilson preserve was previously owned by a timber company for potential harvesting. When TNC purchased the land, Reid said the previous owners had considered selling the land to a wood pellet mill operator.

The Delta, and the land just above it, is an expanse about 30 miles long and 12 miles wide of almost totally undeveloped land from the convergence of the rivers to the mouth of Mobile Bay, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico. It’s full of swamps, bayous, bogs and wetlands, most of which is only accessible by boat.

The area has been dubbed North America’s Amazon, or just America’s Amazon, for the incredible variety of wildlife species within. Ehrlich said the Delta is a prime example of land that should be preserved for the good of humanity.

In his 2016 book “Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life,” Wilson argued that to avoid the looming extinction crisis, half of the land and sea on Earth should be protected.

He called it a “moonshot” goal, since only around 15 percent of Earth’s habitat is currently protected. The foundation is now working to advance that goal by compiling a species protection index to help identify some of the most crucial and species-rich areas for conservation. That includes places like the Mobile-Tensaw Delta.

“It’s an extraordinary resource for us to have at our fingertips right now as we’re thinking about what we really need to do where,” Ehrlich said of the species index. “And this particular place is a model for what we would call places for a Half-Earth future, places that have extraordinary biodiversity that are not only important to the people there, but in the protection of those species’ habitats globally.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,