Even as exposure to floods, fire and extreme heat increase in the face of climate change, a popular tool for evaluating risk has disappeared from the nation’s leading real estate website.

Zillow removed the feature displaying climate risk data to home buyers in November after the California Regional Multiple Listing Service, which provides a database of real estate listings to real estate agents and brokers in the state, questioned the accuracy of the flood risk models on the site.

Now, a climate policy expert in California is working to put data back in buyers’ hands.

Neil Matouka, who previously managed the development and launch of California’s Fifth Climate Change Assessment, is developing a proof of concept plugin that provides climate data to Californians in place of what Zillow has removed. When a user views a California Zillow listing, the plugin automatically displays data on wildfire and flood risk, sea level rise and extreme heat exposure.

“We don’t need perfect data,” Matouka said. “We need publicly available, consistent information that helps people understand risk.”

The removal of Zillow’s data, which came a little over year after it was first introduced, began when the California Regional Multiple Listing Service questioned the validity of flood modeling completed by First Street, a climate risk modeling company, which provides climate data to Zillow and other realty sites.

“Our goal is simply to ensure homebuyers are not being presented with information that could be misleading or unfair. We have no objection to the display of accurate climate data,” the multiple listing service said in a statement.

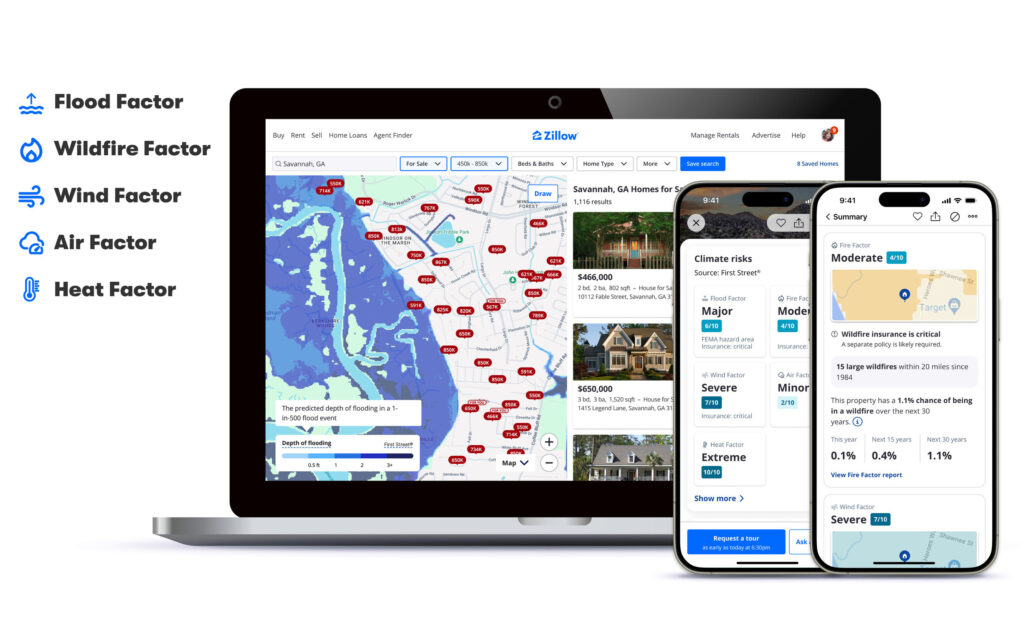

In response to pressure from the listing service, Zillow removed all of its climate risk data, including flood, fire, wind, heat and air quality factors. Zillow still hyperlinks to First Street data in its listings, though it is easy to miss.

“Zillow remains committed to providing consumers with information that helps them make informed real estate decisions. We updated our climate risk product experience to adhere to varying MLS requirements and maintain a consistent experience for all consumers,” Zillow said in a statement.

Other sites, like Homes.com, Redfin and Realtor.com, continue to show First Street climate data in their realty listings.

First Street’s flood map shows more properties at flood risk when compared to the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood maps, which have also been criticized for being outdated.

First Street defended its methodology. “We take accuracy very seriously, and the data speaks for itself. Our models are built on transparent, peer-reviewed science and are continuously validated against real-world outcomes,” First Street said in a statement.

Both independent academic research and research conducted by Zillow has found that disclosing flood risk can decrease the sale price of a home. “Climate risk data didn’t suddenly become inconvenient. It became harder to ignore in a stressed market,” First Street said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowHome by home climate risk predictions still remain notoriously difficult. A residence may, for example, fall right on a FEMA flood risk boundary. One home might be designated higher risk than its neighbor, either as an artifact of the mapping process or because of a real, geographic difference, such as one side of the street being higher than the other. Fire risk mapping, similarly, does not take into account home hardening measures, which can have a real impact on a home burning.

In this way, climate risk models today are better suited to characterize the “ broad environment of risk,” said Chris Field, director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “ The more detailed you get to be either in space or in time, the less precise your projections are.”

Matouka’s California climate risk plugin is designed for communicating what he said is the “standing potential risks in the area,” not specific property risk.

While climate risk models often differ in their results, achieving increased accuracy moving forward will be dependent on transparency, said Jesse Gourevitch, an economist at the Environmental Defense Fund. California is unique, since so much publicly available, state data is open to the public. Reproducing Matouka’s plugin for other states will likely be more difficult.

Private data companies present a specific challenge. They make money from their models and are reluctant to share their methods. “A lot of these private-sector models tend not to be very transparent and it can be difficult to understand what types of data or methodologies that they’re using,” said Gourevitch.

Matouka’s plugin includes publicly available data from the state of California and federal agencies, whose extensive methods are readily available online. Overall, experts tend to agree on the utility of both private and public data sources for climate risk data, even with needed improvements.

“People who are making decisions that involve risk benefit from exposure to as many credible estimates as possible, and exposure to independent credible estimates adds a lot of extra value,” Field said.

As for Matouka, his plugin is still undergoing beta testing. He said he welcomes feedback as he develops the tool and evaluates its readiness for widespread use. The beta version is available here.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,