Lea este artículo en español.

Captured: Second in a series about how pesticide regulators place industry profits above public health.

WATSONVILLE, Calif.—Esperanza was washing off the dirt and sweat from another grueling day in the strawberry fields when she felt a bump on her right breast. It reminded the 44-year-old mother of eight of the milk clumps that formed after she’d weaned her youngest. Except it didn’t go away.

Esperanza, who is undocumented and asked not to use her last name to protect her identity, knew she should seek medical care after hearing PSAs on Spanish-language TV, she said through a translator.

She comes from an Indigenous community in southern Mexico and speaks Mixteco, like a growing number of California farmworkers, and picked up Spanish by watching telenovelas. The local community clinic in Watsonville, a major agricultural hub 90 miles south of San Francisco, couldn’t take new patients and referred her to the county health clinic.

She waited months for a mammogram appointment. When her results were ready, the clinic asked her to come in. Her heart sank. It must be bad if they couldn’t share the results over the phone, she thought.

Esperanza, a slight woman with her dark hair pulled back, looked pained as she recalled the shock of hearing the doctor tell her she had breast cancer.

She told the medical staff she worked in farm fields, but no one informed her that dozens of agricultural poisons increase the risk of cancer or that strawberry growers use copious quantities of particularly toxic, drift-prone pesticides on the soil before planting.

These fumigants are also used on other row crops and orchards, but strawberry growers apply them in the greatest quantities. One of their favorite fumigants—1,3-dichloropropene, also known as 1,3-D or Telone—causes tumors in multiple organs and glands in rodents, including mammary glands, studies show. California listed 1,3-D as a carcinogen in 1989, yet it remains the state’s third highest-volume pesticide.

And in Monterey County, the top-grossing strawberry growing region where Esperanza lives and works, farmers applied more and more 1,3-D even as statewide use declined. Between 2018 and 2022, applications of 1,3-D fell by more than 20 percent statewide, but rose by more than 80 percent in Monterey, according to an analysis by Inside Climate News.

The ICN analysis also suggests that the burden of this pollution falls disproportionately on immigrants with limited English proficiency—people who make up a large proportion of the agricultural workforce.

In the three Census tracts with the most intensive applications of 1,3-D from 2018 to 2022—all in strawberry-growing areas of Ventura and Monterey counties—there were more than twice as many people born in Mexico and other parts of Central America and with limited English skills than in the state as a whole, Inside Climate News found. These tracts also had around twice as many children aged 17 or younger, who are particularly vulnerable to toxic exposures.

Growers often apply 1,3-D in combination with another toxic fumigant called chloropicrin, which was originally deployed as a chemical weapon during World War I. Scientists can’t say whether it causes cancer because it’s so toxic it disables or kills test animals, compromising study results. Applications of this former military choking agent increased by almost 20 percent statewide from 2018 to 2022, with the same vulnerable groups being disproportionately exposed. Health experts worry that 1,3-D and chloropicrin may interact to do more harm to people exposed to both.

Immigrants and agricultural workers exposed to the chemicals come from underserved populations with multiple stressors that increase their susceptibility to toxic exposures, said environmental epidemiologist Paul English, an expert on tracking community health hazards and disparities.

“Lack of access to health care, poverty, poor housing, poor working conditions, all these things make them more vulnerable,” said English, who recently retired from the nonprofit Public Health Institute.

Volatile gases like 1,3-D and chloropicrin pose greater risks for young children, who inhale proportionally higher doses for their body weight than adults and can’t clear poisons as efficiently, research shows.

To gauge children’s potential exposures, Inside Climate News estimated quantities of 1,3-D and chloropicrin applied from 2018 to 2022, the most recent year of data available, within buffer zones extending two distances from the boundaries of school grounds: the quarter mile distance regulated by the state and a mile-wide buffer zone public health experts say is necessary to protect children, teachers and other workers at school sites.

The California Department of Pesticide Regulation, or DPR, prohibits applications of fumigants like 1,3-D within a quarter mile of a campus within 36 hours prior to the start of a school day. But 1,3-D can hang in the air for days and travel for miles on breezes. So health experts have urged pesticide regulators to require a 1-mile safety zone around schools 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

The Inside Climate News estimates are based on an analysis of fumigant applications at the level of “sections” in the Public Land Survey System, which typically measure about one square mile in area, and assumed the chemicals were used evenly across active cropland within each section.

It’s not possible to calculate exactly where the pesticides are applied given the limitations of the available data. But English, who co-led a groundbreaking 2014 study of pesticide use near schools while he was with the California Department of Public Health, reviewed the methods and said the results are reasonable estimates.

The analysis indicated that more than 1,000 schools had 1,3-D applied within a mile of their grounds, almost 800 had chloropicrin applied within a mile and nearly 700 had both fumigants applied within this distance between 2018 and 2022. Looking at the quarter-mile buffer zones, the analysis suggested more than 400 schools had applications of 1,3-D, nearly 300 had applications of chloropicrin and more than 230 had both fumigants used within a quarter of a mile.

The totals varied widely, but for the most heavily exposed schools, estimates of applications within a mile-wide buffer zone exceeded 100,000 pounds for each fumigant. For Ohlone Elementary School, near Esperanza’s home south of Watsonville, estimated applications totaled about 10,000 pounds of 1,3-D within a quarter mile and more than 100,000 pounds within a mile; for chloropicrin, estimates were more than 35,000 pounds and 375,000 pounds respectively.

The findings provide “eerie echoes” of the 2014 report, which showed disproportionate impacts of pesticide use near schools on Latino schoolchildren, particularly in Monterey County, said Gregg Macey, director of the Center for Land, Environment and Natural Resources at the University of California, Irvine School of Law. In the report, Monterey County had the highest percentage of schools and students potentially exposed to the most dangerous pesticides, and Latino children were nearly twice as likely as white children to attend schools near the heaviest applications.

“California regulators are drowning in what they like to call ‘world class’ pesticide use data,” said Macey, who recently documented “ongoing and pervasive” civil rights violations from the adverse and disproportionate impacts of pesticides on Latino and Indigenous members of California agricultural communities. But even with properly analyzed data, he said, “little is done to protect children, students or workers.”

English said risks for schoolchildren appear to have increased since he and his team reviewed pesticide applications from 2010.

“Although the methods are not completely comparable, this new analysis suggests that several schools in vulnerable populations have had increased poundage of applications of 1,3-D and chloropicrin since the 2014 report,” he said, referring to the ICN findings. “This worrisome trend should send alarms about increased risks to schoolchildren.”

DPR officials know 1,3-D lingers around schools and neighborhoods from the air monitors they’ve deployed in several counties on campuses, including Ohlone Elementary. But the agency has set regulatory targets for bystanders that allow substantially higher exposures than the level state health scientists say is safe.

DPR takes its mission to protect human health and the environment by fostering sustainable pest management and regulating pesticides “very seriously,” said Leia Bailey, the agency’s deputy director of communications and outreach. “DPR and county agricultural commissioners, and their collective 500 staff across the state, enforce pesticide use laws and regulations, including enforcing pesticide restrictions around school sites.”

She also noted that the Inside Climate News analysis is based on pesticide applications that predate new restrictions enacted this year to protect people who live near treated fields.

The fact that the pesticide use records posted on the state’s website are two years old frustrates pesticide-reform groups, who have long requested real-time data to help protect students, workers and communities. On December 19, DPR finally approved a measure to make information about planned soil fumigations publicly available starting in March. But advocates say the rule doesn’t require specifying the exact location of the fields being treated, so it will do little to protect communities.

Down by Law

Use of 1,3-D and chloropicrin is prohibited in more than 30 countries, including the 27 in the European Union.

In the United States, by contrast, Dow Agrosciences, the chemical’s primary manufacturer, has managed to keep the pesticides’ use–and profits–humming.

At Dow’s insistence, the U.S. EPA recently agreed to use a novel approach to ignore cancer responses in lab animals that occurred at certain doses, as Inside Climate News reported. The company had less luck with the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, or OEHHA (pronounced oh-E-ha), which rejected Dow’s entreaties to ignore those cancer responses as well as tumors in animal studies caused by inhaling 1,3-D, a primary route of exposure—approaches Dow said justified setting a much higher target than OEHHA had determined to be safe.

California’s DPR, however, adopted Dow’s level as a regulatory target to mitigate cancer risks of 1,3-D to bystanders, including residents and schoolchildren.

Dow did not respond to requests for comment.

That DPR and OEHHA, sister agencies under California EPA, could arrive at such different conclusions about what level of a cancer-causing chemical is safe, pesticide-reform critics say, reflects the outsize influence of economic concerns and DPR’s interest in keeping pesticide manufacturers and growers happy.

DPR, however, insists that its regulations are designed to protect public health.

As a science advisory agency, OEHHA evaluates the health risks of chemicals and sets levels it determines pose no significant risk of cancer for regulatory agencies like DPR. At a public meeting last February, Mark Weller, the campaign director for the statewide coalition of public-interest groups Californians for Pesticide Reform, asked CalEPA Secretary Yana Garcia how the two agencies could better reconcile their conclusions about what people can be exposed to safely, to protect farmworkers and their communities. “We need to do more to align our efforts,” Garcia said, adding that regulatory targets should be set to the more health protective level.

Californians who live, work and attend school near fields enjoyed a brief reprieve from 1,3-D years ago, after regulators detected unusually high levels of the fumigant in the air.

In 1990, California banned 1,3-D after a monitor measured it at unacceptably high levels at a junior high school in Merced County, where it’s used mostly on sweet potato fields.

But four years later, DPR again allowed the use of 1,3-D with several restrictions, including a limit on how much could be applied within an area called a township, roughly 36 square miles in area. DPR also entered an agreement with Dow (then DowElanco) to manage the risks of 1,3-D exposure through a township emissions cap program.

In 2015, OEHHA scientists warned DPR that it was underestimating the cancer risk 1,3-D poses to nearby workers and residents, and failing to account for children’s increased sensitivity or for risks from co-exposure with chloropicrin.

Two years later, Californians for Pesticide Reform sued DPR on behalf of a Ventura County strawberry harvester named Juana Vasquez who lived with her family near 1,3-D treated fields and whose children attended schools near high-use areas. The agency “abused its discretion,” ignored OEHHA’s advice and flouted regulatory rules to allow a 22.5-fold increase in 1,3-D applications between 1999 and 2014, the complaint stated.

A California court agreed in 2018, calling the agency’s arrangement with Dow “a questionable outsourcing of a government regulatory function.”

Dow appealed the decision and DPR joined the appeal as an “interested party,” arguing that the agreement between the agency and the company to manage emissions was not a regulation. But the appeals court rejected their argument in 2021. When the agency finally released its draft regulation in 2023, it was for “non-occupational bystanders,” which skirted a legal requirement to collaborate with OEHHA on worker safety rules and enabled it to set a substantially higher regulatory target than state health scientists recommended.

“OEHHA set a level for all Californians, but it’s meaningless if the only people who are actually exposed to this chemical don’t have the benefit of that level,” said Jane Sellen, co-director of Californians for Pesticide Reform.

Sellen’s group sued DPR again last year, and the judge ordered the agency to comply with the original court order to draft regulations in keeping with the law.

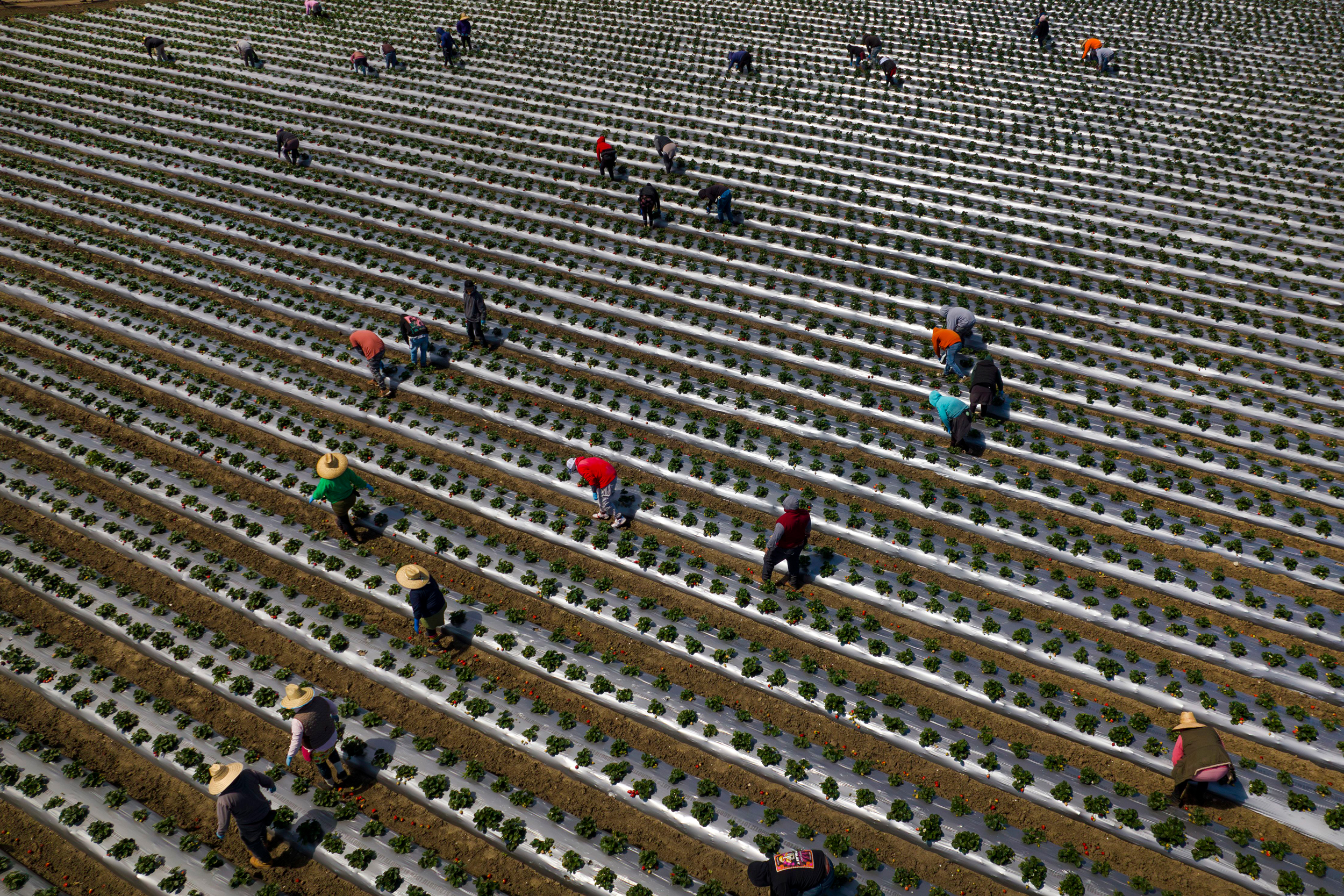

The highest applications of 1,3-D and chloropicrin occur in the strawberry fields that earned California growers nearly $3 billion last year and require back-breaking labor to harvest.

Last month, seven years after DPR was first sued for failing to comply with state rulemaking requirements, the agency released a draft standard for workers who labor near treated fields, setting a regulatory target five times higher than the level OEHHA said would reduce lifetime cancer risk.

“OEHHA set a level for all Californians, but it’s meaningless if the only people who are actually exposed to this chemical don’t have the benefit of that level.”

— Jane Sellen, Californians for Pesticide Reform

DPR’s target assumes workers could be safely exposed 40 hours a week over 40 years, Sellen said. But most farmworkers, like Esperanza and Vasquez, live with their families near their job site, so their combined exposures are much higher than what DPR assumed.

The agency also assumed workers’ shifts go from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., Sellen said. But most farmworkers start before 7 a.m., and will start even earlier as climate change brings more heat waves, putting them in the fields in the early morning and nighttime when there is less wind to dissipate fumigant emissions and atmospheric conditions tend to hold them close to the ground.

These assumptions allow DPR to say it’s using OEHHA’s safety target to protect workers near treated fields, Sellen said. “But it still doesn’t protect children. It still doesn’t protect residents. And it still doesn’t protect farmworkers because it doesn’t account for their background exposure when they go home.”

DPR’s Bailey said the proposed regulation will “work in concert” with the residential bystander rule to reduce potential exposure in the highest 1,3-D use areas. She also said the agency will review any new data regarding hours workers are present in areas near 1,3-D-treated fields and how it impacts potential occupational exposure.

A Long History of Discrimination

A quarter century ago, the U.S. EPA ruled that California farmers’ pesticide use disproportionately impacted people of color, primarily Latino children. At the time, methyl bromide, a potent neurotoxic chemical, was strawberry growers’ preferred fumigant. Growers cover fumigated fields with special plastic tarps intended to trap the gases in soil. But pesticide-reform groups say winds can loosen the tarps, which can also leak from wear and tear.

After a report by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group showed that growers were applying tens of thousands of pounds of the fumigant near schools attended mostly by Latino kids, a group of parents from Monterey and Ventura counties filed a civil rights complaint with the EPA.

In 2011, nearly 12 years later, the EPA announced it found “an unintentional adverse and disparate impact” on Latino children from methyl bromide. During that time, growers reduced reliance on methyl bromide, which depletes the ozone layer, and increasingly turned to 1,3-D and chloropicrin.

But the agency did not limit use of methyl bromide or require safer alternatives. Instead, it required DPR to carry out air monitoring in Monterey and Ventura counties and install an additional air monitor at Ohlone Elementary School, south of Watsonville, one of the most affected areas.

That monitor, like others around the state, has routinely detected 1,3-D levels above the amount OEHHA determined would not pose a significant cancer risk in 2022.

California’s strawberry industry maintains that the state’s strict regulations minimize risks from fumigants. Strawberry farmers have invested more resources than any other commodity group in the world to control soil-borne diseases, leading to new technologies that reduce fumigant emissions and boost strawberry plants’ ability to resist diseases, said Jeff Cardinale, California Strawberry Commission communications director.

Yet many people who live and work in strawberry-growing regions do not understand how the industry can continue to rely so heavily on such toxic chemicals.

When Melissa Dennis started teaching third-grade at Ohlone Elementary in 2010, she was enchanted by the storybook quality of a country school nestled amongst strawberry fields. She imagined getting to know the farmer across the street and taking her students to frolic through his fields picking strawberries.

Then she learned how farmers grow strawberries and realized that idyllic jaunt she’d daydreamed about was “totally out of the question.”

“Getting anywhere near a productive strawberry field is just completely insane if you care about your health at all,” Dennis said. “Strawberries are the most toxic agricultural product in existence.”

Third-grade teacher Melissa Dennis (left) stands in the courtyard of Ohlone Elementary School in Watsonville, where a monitor (right) near the school playground has long detected unsafe levels of 1,3-D. Credit: Liza Gross/Inside Climate News

Dennis was livid when she learned that DPR had set a safety level for residential bystanders this year so much higher than state health scientists say is safe.

“That was a slap in the face,” she said. “Basically, we were exposed to a dangerous level of 1,3-D, and the only help we got from the Department of Pesticide Regulation was to change the definition of what’s dangerous, not change the amount of chemicals we’re being exposed to.”

When she started teaching at Ohlone, Dennis noticed how many kids had serious learning problems and needed special education. Then she saw how many had “really bad” asthma. And cancer.

“I had a student with leukemia,” Dennis said. “Then, a few years later, I had a student with a brain tumor, who had that brain tumor removed but then she was left legally blind and had to have an aide.”

Another student had cancer in first grade. The hair she lost to chemotherapy grew back and she’s cancer-free but is now in special ed because she fell so far behind while spending so much time in the hospital.

Childhood cancer is so rare that many teachers may never see a cancer patient in one of their classes, experts say. Seeing three students in her classes battle cancer, and knowing most of their parents work in the strawberry fields, Dennis is convinced there’s a connection. So is her colleague, kindergarten teacher George Feldman.

For many years, Feldman would close his classroom door when he smelled a strange odor coming from the field across the street. He’s seen students grapple with cancer and one lose a parent to the disease.

Then, last year, he was diagnosed with colon cancer and spent the first three and a half weeks of school recovering from surgery. He decided on a course of preventive chemotherapy to forestall a recurrence.

“We need to minimize pesticide use,” he said. “I cost the school thousands of dollars when I had to be out of school for months. Surely we could decrease the number of cancer-causing materials in my life rather than pay for that.”

On a breezy spring afternoon, Dennis walked to the air monitor next to the Ohlone playground as kids squealed and shouted a few yards away.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“DPR tells us they try to take random samples,” she said, clearly frustrated. She wants the monitor timed to fumigations, especially when growers treat soil with the highest amounts before planting in the fall, which locals call “Telone season.”

If monitor readings and application notices were shared in real time, she said, teachers could try to minimize exposure for students and themselves.

“When we won that lawsuit, the only thing we got was a monitor to show that we are being exposed,” Dennis said, referring to the 1999 civil rights complaint. “But nothing has been done to reduce the amount of exposure that our students are living with.”

Pushing Back

When the tarps meant to trap fumigant emissions tear, they can not only expose bystanders but also create serious hazards for workers.

Several years ago, Esperanza was hustling through a field hoisting a heavy box of strawberries above her head when her foot got caught in a ripped tarp. She lost her balance, twisted her ankle and landed on her back. The supervisor told her to walk it off, but her back pain didn’t go away. In the emergency room she learned she broke a disc.

It’s possible she also got a dose of 1,3-D or chloropicrin. Fumigants can leak from soil for weeks if exposed to air. DPR logged nearly 375 incidents of “definite” or “probable” illness related to the chemicals for workers in or near treated fields between 2010 and 2020, the most recent available data shows.

Rocio Ortiz was a Watsonville High School student when she started taking summer shifts in the strawberry fields to save for college. She knew a little about what to expect because her parents, Mixtec immigrants from Oaxaca, had picked California strawberries for more than 20 years.

Now an 18-year-old freshman at Cal State Monterey Bay, Ortiz didn’t realize how dangerous field work could be until last summer, when she and her older sister caught wind of a “strong, nasty” odor. Their eyes started burning and their skin itched. Ortiz saw someone in protective gear on a tractor applying pesticides in the next field over. Her supervisor told her to not worry about it and wear a bandana.

Employers are required to keep workers out of fields where pesticides are being applied, an exclusion zone that extends 100 feet from application equipment. They also must alert workers about recent applications or post warning signs in treated fields. Neither happened on that day, Ortiz said.

“If I knew I could have reported that someone was using pesticides near us, I would have filed a complaint,” said Ortiz, who co-founded the youth environmental justice group Future Leaders of Change.

Over the course of just three weeks in the fields where she picked strawberries last summer, growers applied thousands of pounds of chloropicrin and 1,3-D-based products, data obtained through a public records request shows.

Now Ortiz wonders whether all the years her family worked in the strawberries contributed to their health problems. Ortiz’s mom had a miscarriage about 20 years ago, and then her younger sister was born with asthma. Just four years ago, they had to rush her dad to the hospital after he struggled to breathe, developed severe headaches and started vomiting following a day in the fields.

It’s not possible to say for sure whether pesticides were to blame. But mounting evidence links pesticides to increased risk of miscarriage, asthma and headaches, nausea and shortness of breath, among other health ills.

“DPR is supposedly there to protect the public,” said Yanely Martinez, an organizer with Californians for Pesticide Reform who served eight years on the city council of Greenfield, south of Watsonville. “But they’re not doing that.”

“The biggest thing that upsets all of us, especially the organizers working in these communities that are affected, is that this shouldn’t even be happening,” said Martinez, a daughter of farmworkers who migrated decades ago from Mexico.

Last month, pesticide-reform advocates staged a protest in Watsonville outside a movie theater showing student-made films about living with pesticides. Teachers, students, farmworkers and community members called on regulators to end “separate and unequal” regulation of 1,3-D while holding signs saying “Our kids deserve better” and “If it’s dangerous, find something safer.”

“This is a racist attack on our farmworking communities, and it’s coming not from Trump,” Martinez said to the crowd, referring to the president-elect’s promise of mass deportations, “but from our own state institution.”

1,3-D is a painful reminder that the American Dream is an illusion for migrant farmworkers, Martinez told Inside Climate News.

“A lot of our immigrant folks don’t have health insurance,” she said. “They get horrible treatment at work, like Esperanza. The pay is horrible. And then to top it off, you’re being poisoned.”

Dennis, the Ohlone Elementary School teacher, is thankful that at least one farmer is cutting back on poisons. The farmer across the street switched to growing organic strawberries a few years back.

“We have been doing field trips with him,” she said, her dream of frolicking in the fields with her students a reality at last.

“That’s the one whose hair grew back,” she said, beaming as she showed photos on her phone. “She’s so cute.”

“We’re pushing back,” Dennis said. “But it’s like pushing back droplets with a tsunami of toxic chemicals that are being used around us.”

An earlier version of this story misstated the hours in which the California Department of Pesticide Regulation prohibits applications of fumigants like 1,3-D within a quarter mile of a school campus. The department prohibits application within 36 hours prior to the start of a school day, not from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. on school days.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,