Second in a series about rising electricity prices in Pennsylvania. Read the first story here.

PHILADELPHIA—In the steep hills above the Schuylkill River, across the street from a famous cheesesteak place and at the end of a quiet block, sits a typical Philadelphia rowhouse: narrow brick, front porch, fig trees growing in the yard. From the sidewalk, there’s nothing to distinguish this house from its neighbors. But there’s a tiny clue that something is a little different: a sticker on the electric meter with a Solarize Philly logo.

The owner, Liz Robinson, is the current executive director at the Philadelphia Solar Energy Association, a volunteer-based nonprofit that works to increase solar adoption in Pennsylvania. She’s been involved in renewable energy policy in the city and on the state level for decades. Almost 10 years ago, Robinson had solar panels installed on the roof of this house, which she bought as a rental property.

Wearing an “electrify your future” T-shirt, Robinson pointed at the digital readout on the meter. “This is telling me how much electricity is being produced, and even on a cloudy day like today, I’m getting a fair amount of electricity,” she said. Her small system covers the electricity bills for this property and 60 percent of the bill at her house down the street.

“I thought it would pay for itself in 10 years, but because electricity prices have been rising, it paid for itself in less than nine years,” she said. “It’s the best defense against a rising electric bill.”

Robinson remembers a time when the dream of widespread renewable energy for Pennsylvania, and not just for scattered individual households, felt within reach. In the early 2000s, the state was a renewable-energy pioneer, passing a law that required a certain percentage of the state’s electricity generation to come from alternative energy sources.

In 2010, then-Gov. Ed Rendell boasted about this Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard, calling it “one of the most ambitious of its kind in America” and praising Pennsylvania as “a national leader in the field of alternative energy.” Since 2006, Rendell said, the state had made “remarkable progress,” citing growth in wind and solar generation.

“The Rendell administration did a lot of work to bring manufacturing into the state,” said Laurie Mazer, co-founder of Formation Energy, a Philadelphia-based solar developer. “There really was this moment where Pennsylvania was well ahead of the curve.”

But even as Rendell touted the state’s investment in renewable energy, the landscape was changing. In 2004, the same year the state enacted the AEPS law, drilling began on the first gas well in Pennsylvania to use hydraulic fracturing.

The fracking boom birthed a new way of thinking about energy. By 2013, in a speech about climate change, President Barack Obama was hailing natural gas as a “transition fuel that can power our economy with less carbon pollution,” phrasing that was popular in messaging on natural gas at the time. It was a “bridge” from dirty coal to cleaner renewables, a temporary solution that would lower emissions and secure energy independence.

Fifteen years later, that bridge extends endlessly into Pennsylvania’s future, with no glimpse of the other side in sight.

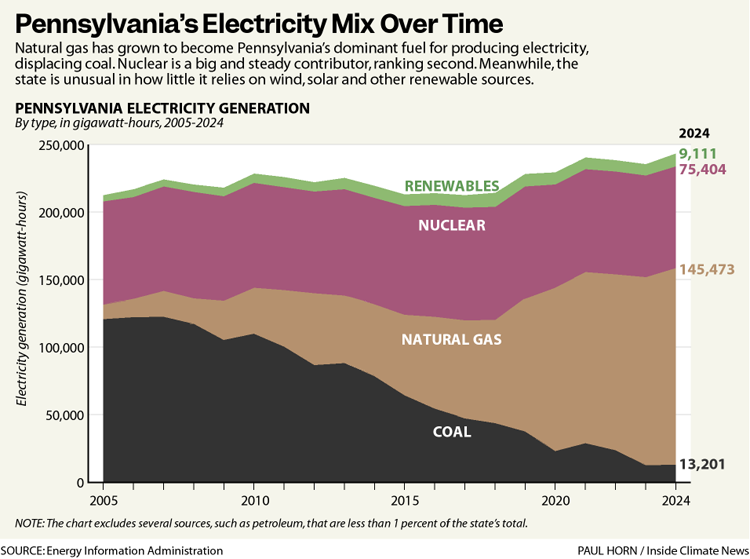

Natural gas production is still rising in the United States, and 60 percent of Pennsylvania’s electricity generation now comes from natural gas. It’s so tied to electricity in some Pennsylvanians’ minds that they can’t imagine how the state could run without it. State Sen. Camera Bartolotta, a Republican who represents a heavily fracked district in the southwest, appears on a billboard on the turnpike with this message: “No fossil fuels, no electricity. Wake up America!”

Only 4 percent of Pennsylvania’s electricity comes from renewable energy. Since 2015, that number has only increased by one percentage point, even as states such as Texas, Kansas, Iowa, South Dakota and Maine saw significant gains in renewables.

Pennsylvania now ranks second to last in the country when it comes to the percentage of its electricity generated by renewables, and in 2024, the state ranked 49th for renewable energy growth in the U.S. For utility-level solar, Pennsylvania ranked 41st, supplying just over 1 percent of the state’s electricity. For residential solar systems like Robinson’s, a separate metric from utility-level power generation, Pennsylvania is a middling 26th.

Pennsylvania’s reliance on gas is one of the problems at the root of the state’s soaring electric bills, experts say, because it means local consumers pay more whenever global gas prices go up.

In Texas, the only state that produces more gas than Pennsylvania, renewable energy’s share of the electric market has grown from 12 percent in 2015 to 34 percent in 2024. And residential electricity rates in Texas are about 20 percent lower than Pennsylvania’s, according to June federal figures.

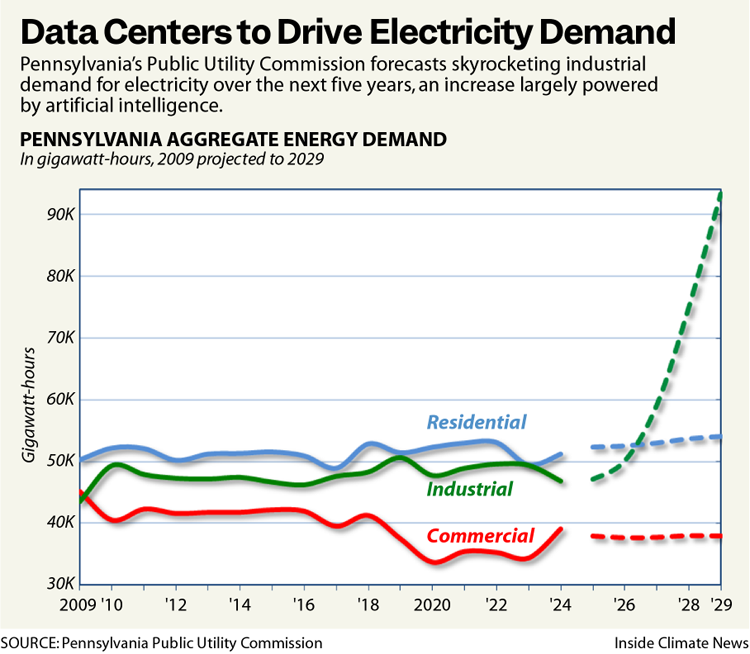

Electricity prices in Pennsylvania continued to rise in 2025, following a sharp increase over the last few years that has hit Pennsylvania households hard. One reason for the most recent surge: data centers and the stress they are likely to put on the grid. New data centers are expected to drive soaring increases in electricity demand over the next five years, according to forecasts from Pennsylvania’s Public Utility Commission. To power them, investors want to build even more natural gas power plants.

“We have become over-reliant on gas as a transitional fuel, and we continue to argue that it’s a transition, yet we are not transitioning,” said Elizabeth Marx, the executive director at the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project. “We continue to build out our delivery system for gas, and we are locking ratepayers in to pay for that system for 30 more years.”

“Clean Energy Now”

Robinson traces the origins of Pennsylvania’s failed promise as a leader in renewables to one big shift over the past 15 years.

“The change in the Republican Party is really the story here,” she said.

When she first started working in the field, moderate Republicans in Philadelphia’s collar counties were passionate advocates for conservation initiatives and open-minded about ideas like green energy. As Tea Party candidates and increasing polarization pushed this older generation of Republicans out of office, the legislature became more partisan, more contentious and less willing to compromise.

“It surprises me, in this day and age, how many climate deniers you have in the legislature. There’s this almost visceral disdain for solar and wind.”

— Rep. Greg Vitali, D-Delaware County

At the same time, fracking gained ground in Pennsylvania, and natural gas companies poured money into Harrisburg, both through campaign contributions and lobbying. One example: the American Petroleum Institute, an industry trade group, spent more on lobbying in Pennsylvania than in any other state in 2022, according to a Public Accountability Initiative analysis. “There’s a tremendous ownership of politicians that goes on in Pennsylvania by the gas industry,” Robinson said.

The resulting gridlock is particularly acute when it comes to energy issues. Anything that seems to threaten the dominance of natural gas is politically doomed. From the state’s contested membership in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative to updating the Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard to legalizing community solar, efforts to make real policy changes at the state level have met with resistance.

“It surprises me, in this day and age, how many climate deniers you have in the legislature. There’s this almost visceral disdain for solar and wind,” said Rep. Greg Vitali, a Democrat from suburban Delaware County who has served in the state legislature for more than 30 years and is considered an environmental leader at the capitol. “It goes beyond an intellectual disagreement.”

Vitali, the chair of the House Environmental & Natural Resource Protection Committee, said there was effective negotiation and “give and take” when the Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard passed in 2004. That isn’t happening now.

One component of Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro’s Lightning Plan for energy reform is a bill to allow community solar, where customers can buy shares in a solar project even if they can’t host panels on their own roofs. The bill passed the Democrat-controlled House in May, but it’s now stuck in the Senate, where Republicans maintain a narrow majority. Republicans have controlled the Pennsylvania Senate since 1994.

Elowyn Corby, the mid-Atlantic regional director at Vote Solar, an affordable-solar advocacy group, said this state of affairs on renewables doesn’t reflect the feelings of the public. “It’s less about what Pennsylvanians want, because we’ve seen time and time again that when asked, Pennsylvanians like renewable energy. Pennsylvanians love solar,” she said.

The state legislature’s paralysis has effectively ceded leadership of energy policy to other forces, said Mazer, the solar developer. “We haven’t played as much of a role as we could have in deciding what our energy future looks like,” she said.

There’s another kind of energy gridlock at PJM Interconnection, the company that manages the electricity grid in all or parts of 13 states and Washington, D.C. When it comes to Pennsylvania’s emphasis on natural gas generation, PJM is a significant part of the problem, said David Masur, the executive director at PennEnvironment, an environmental organization in Pennsylvania that has closely tracked the state’s lagging investment in renewable energy.

“There’s just hundreds of projects in the queue, and something like 98 percent of them are renewables,” he said.

PennEnvironment estimated that PJM’s backlog of unapproved electricity projects could cost Pennsylvanians $12.5 billion in just one year. In January, after filing a complaint against PJM, Shapiro settled with the operator to stop a rate hike that could have tripled energy prices for Pennsylvanians.

If the system were working the way it’s supposed to, more solar and wind projects would have been coming online as their costs drop compared to gas. Instead, PJM’s delays have created a bottleneck.

“New competition is being blocked by this outmoded, vastly delayed interconnection system,” Corby said. “New energy is not able to come online quickly enough to keep our bills down. PJM needs to move a lot more things through the queue a lot more quickly.”

In a statement to Inside Climate News, a spokesperson for PJM, Jeffrey Shields, said the company has reformed its interconnection process, processing 140 gigawatts of capacity since 2023, with 63 more due to be processed in 2025 and 2026. PJM blames the slowdown on permitting and supply chain backlogs, “none of which are related to PJM,” and nationwide trends that are beyond the company’s control.

“Electricity supply is decreasing while demand is increasing, primarily from data centers, not only in PJM but across the country,” Shields said.

On a rainy day in May, protestors stood in front of PJM’s headquarters outside Philadelphia. Dressed in rain slickers and clutching umbrellas, the protestors held hand-painted signs reading, “Clean Energy Now” and “PJM, lower our electric bills. Connect clean energy.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowAs cars zoomed behind him, state Rep. Chris Rabb spoke to the protesters and members of the press about his bill to increase transparency in PJM’s decision-making. Rabb, a Democrat, said he believed his bill could attract bipartisan support, a rare feat in Pennsylvania’s split legislature.

“The reason I think this might have some legs is because so many of our constituents—rural, urban, suburban—are struggling to pay their utility bills. And it’s only going to get worse if PJM continues to operate in this fashion,” he said. “I think it can garner some Republican votes, because they have ratepayers, too, who are not happy about the coming hikes. People are going to be mad as hell, right? They’re going to wonder who to blame.”

Powering the Future

Data centers built to power electricity-hungry artificial intelligence technology are projected to consume enormous quantities of power, and in Pennsylvania, gas producers see an opportunity to keep extending the “bridge.”

At Republican U.S. Sen. Dave McCormick’s Energy and Innovation Summit in Pittsburgh in July, $90 billion in data center deals between tech companies and natural gas and pipeline companies were announced. These investments could lock in gas as the state’s primary electricity generator for another generation.

“There’s a slowing of production growth happening here in the United States, and the so-called shale revolution is in the later innings.”

— Trey Cowan, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

EQT, a natural gas company headquartered in Pittsburgh, said it would become a partner in a plan to convert the old coal-fired Homer City Generating Station into a 3,200-acre artificial intelligence campus with the country’s largest gas-fired power plant.

“This agreement ensures long-term energy security for the data center campus, while demonstrating our commitment to powering the future with Pennsylvania gas,” Corey Hessen, one of the leaders of the Homer City project, said in a statement.

Meanwhile, the costs of drilling for gas are going up. “There’s a slowing of production growth happening here in the United States, and the so-called shale revolution is in the later innings,” said Trey Cowan, an oil and gas energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “It’s getting more and more expensive to drill.”

It’s also getting more expensive to build natural gas power plants, said Sean O’Leary, senior researcher in energy and petrochemicals at the Ohio River Valley Institute: “The cost of building a gas-fired power plant has gone up by about two-and-a-half times.”

That could pose problems if all of the gas power plants that PJM thinks it will need to meet growing demand over the next decade are built. Trump’s massive tariffs on steel are likely to further inflate costs, said Christopher Doleman, an LNG and gas specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

And the premise that the bridge was originally built on—that natural gas made sense as a transition to renewables because it emitted fewer greenhouse gases than other fossil fuels—turns out to be far more complicated than the politicians of the 2010s claimed.

Although it’s true that burning natural gas emits fewer greenhouse gases than coal, evidence is growing that its production and transport damages the earth’s atmosphere more than previously thought. Methane is a far more potent driver of global warming than carbon dioxide.

Despite all that, both Corby and Robinson see reasons for hope. One of them is residential solar systems like Robinson’s, which are small enough to bypass the clogged PJM queue.

“It can come online incredibly quickly. It also takes much less time to build,” Corby said. “That’s a really intuitive and easy place to look, where we would see the results quickly.”

“It’s important that we remember Pennsylvania’s ability to do good things on energy has not been exclusively on the side of fossil fuels.”

— Elowyn Corby, Vote Solar

More Pennsylvanians are clamoring to install solar panels of their own, especially as electricity prices go up. Residential solar installations increased in Pennsylvania in 2022 and 2023, according to the most recent data from the Solar Energy Industries Association. George Otto, a retiree in State College, said he decided to do so after years of watching Pennsylvania politicians fail to make progress on environmental or climate issues.

“It’s like pushing a rope to get those guys to move on any of this stuff. And so I figured, if we’re not going to be able to do it through them, then each of us can do what we can within our sphere of influence,” he said. “Now I’m happy to provide an example for others to look at and say, ‘Hey, this can work here.’” In addition to reducing his carbon footprint, Otto now pays nothing for electricity.

Pennsylvania has the potential to catch up on renewables, but it needs the political will. Even incremental shifts in power could do that, Robinson said. “Having the House be led by Democrats, even a one-seat majority, has made a world of difference,” she said. “If we can win the Senate, I think that changes everything.”

Corby is heartened by the state’s not-so-distant successes with renewable energy. “It’s important that we remember Pennsylvania’s ability to do good things on energy has not been exclusively on the side of fossil fuels,” she said.

“The question now is, as energy affordability and supply issues become increasingly pressing, will we let ourselves be bogged down by that history or enabled by it to lead again?”

For his part, Vitali has continued to introduce bills that could change the state’s trajectory, even if they have little chance of becoming law.

“There’s a quote I used to have [on] my desk. It said, ‘A leader should be a dealer in hope.’ I don’t feel very hopeful now,” he said. “But we try every day.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,