Lea este artículo en español.

Captured: Third in a series about how pesticide regulators place industry profits above public health.

SALINAS, Calif.—Residents of farmworker communities and their allies packed into a Monterey County meeting room about 100 miles south of San Francisco last Thursday night with a message for state pesticide regulators: protect us from the cancer-causing fumigant 1,3-D.

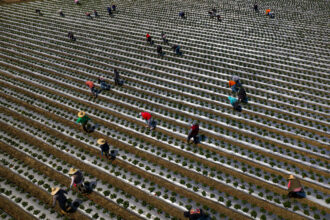

California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation, or DPR, held the third of four hearings in Salinas, a major berry-growing region, to seek public comment on its proposed regulation of 1,3-dichloropropene, or 1,3-D, a fumigant used most intensively by strawberry growers.

The agency says the draft rule is driven by science and will protect farmworkers from being exposed to 1,3-D applied in neighboring fields. But scores of commenters at this and earlier hearings said the rule is too weak and urged DPR to either ban or substantially restrict use of a chemical California classified as a carcinogen in 1989.

Many testified to having cancer or other chronic diseases from pesticide exposure or seeing loved ones, neighbors or coworkers grapple with similar ills. As the two-hour hearing went on, speakers’ voices rose with frustration and the crowd’s polite clapping after people spoke switched to rowdy whoops and shouts. With half an hour to go, dozens of protesters forced the hearing to stop, dropping to the floor to play dead while holding pictures of cancer victims, as others marched around the room carrying banners and chanting what has become their rallying cry: “DPR, you can’t hide, we can see your racist side!”

Before protesters took over the meeting, farmworkers, their children, community organizers, students, doctors, nurses, teachers, mothers and grandmothers, many speaking in Spanish, implored regulators to take their concerns seriously.

Speakers told regulators they were ignoring how pervasive pesticide exposure is for farmworkers and their families, even away from the farm fields, making regulators’ assumptions about 40-hour work weeks moot. How they are exposed to pesticides from the womb to the grave. How workers begin their shifts hours before the proposed rule assumes, when weather conditions can keep fumigants near the ground and increase exposure.

Many appealed to regulators’ sense of fairness with emotional stories illustrating how the department’s policies hurt mostly the people who feed the nation, primarily Latino and Indigenous workers, and their families.

“I am here on behalf of Future Leaders of Change, as a co-founder, and more importantly, as a member of my community, which for many years, like many other communities, in our Central Valley, in our Central Coast, have been ignored and have been allowed to suffer under the watch of the Department of Pesticide Regulation,” said Victor Torres, a freshman at Monterey Peninsula College whose grandparents left Mexico to work in the nearby fields.

Torres was just 10 years old when he was rushed to the hospital from class after pesticides applied near his middle school triggered a life-threatening asthma attack. He started advocating for pesticide reform as a student at Greenfield High School, south of Salinas.

Even though 1,3-D is now banned in 40 countries, it’s still the third-most used pesticide in California, Torres said. “This cannot be allowed to continue under your watch. DPR, do your job. I should not have to continue repeating this. It’s really sickening how we have to continue coming up here, pouring out our story, pouring out our hearts of our suffering, yet nothing is done. All we ask for is adequate regulation.”

The Department of Pesticide reform does not have a system in place to safeguard any farmworking community from the elevated levels of 1,3-D in the Salinas Valley, said Ana Barrera, a Salinas high school teacher.

Air-monitoring systems need to be in place at every local school to detect drift and allow for emergency procedures to protect students and staff, Barrera said. “We need the exact location of the use of any pesticides,” she said, adding that the agency’s proposed 100-foot buffer zones “are entirely inadequate for protection against fumigants that can drift for miles at harmful levels.”

Kari Aist, who worked as a substitute teacher for years in Ventura County, another major strawberry-growing region, charged DPR with “proposing a policy that disproportionately harms Latino and Indigenous farmworker communities and perpetuates environmental racism. That is an absolutely unacceptable situation,” she said, after submitting an Inside Climate News article for the public record.

The Inside Climate News analysis, published in December, found that even as applications of 1,3-D fell by more than 20 percent statewide between 2018 and 2022, they rose by more than 80 percent in Monterey County. The analysis showed that the disproportionate burden of this pollution falls on immigrants with limited English proficiency—as is the case with most of California’s farmworker population and many at the hearing.

“No Justice, No Peace”

Pesticide-reform advocates and the workers and communities they represent have repeatedly asked state pesticide regulators to adopt the cancer risk level set in 2022 by the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, or OEHHA, which oversees the state’s right-to-know law.

“You ignored OEHHA’s legal lifetime cancerous thresholds when implementing the regulation for residential bystanders,” said Mark Weller, campaign director for Californians for Pesticide Reform, a statewide coalition of public-interest groups, referring to a rule adopted last year.

As for the occupational bystander draft rule, Weller said, “If there is a farmworker in fields near where 1,3-D is applied who only works 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. five days a week for 40 years and is never exposed to 1,3-D before or after work, including childhood and retirement, then that farmworker might be protected. But we all know that farmworker doesn’t exist.”

DPR developed the proposed occupational bystander regulations “jointly and mutually” with OEHHA and adopted its recommended air concentration target as the basis for the regulations, said DPR spokesperson Leia Bailey.

Bailey said that the residential and occupational bystander regulations work together to address risks to both people working in the fields and those living near them from the use of 1,3-D. “In addition,” she said, “the proposed regulation builds in triggers for additional restrictions and regulatory actions if the target air concentrations are exceeded.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowDPR environmental program manager Ann Schaffner explained at the hearing that the agency will evaluate 1,3-D air concentrations at existing monitoring stations to ensure that the requirements for both residents and workers are protective. But the state doesn’t have air monitors at most locations where 1,3-D is applied, including around Salinas. And the agency has not proposed providing real-time notifications to communities if concentrations exceed its regulatory targets.

Authoritative scientific bodies like the Center for Disease and Prevention warn there is no safe level of exposure to a carcinogen. Pesticide-reform groups and the farmworker communities they represent have appealed to DPR for years to tighten restrictions on 1,3-D. They maintain that California still allows heavy use of such dangerous compounds like 1,3-D because of pressure from economic interests.

Agricultural and chemical manufacturing interests spent more than $3.4 million between 2015 and 2024 to influence California legislators and agencies, including DPR and OEHHA, about 1,3-D and other issues, a review of state lobbying disclosure records shows. Only one public-interest group, the nonpartisan Friends Committee on Legislation of California, lobbied state officials about 1,3-D, records show. Their filing shows that they spent around $17,700 and asked DPR to adopt a single health-protective standard of 1,3-D for all Californians, “ensuring equal protection from this carcinogenic pesticide.”

Filings by industry groups, including Dow, 1,3-D’s manufacturer, and growers’ trade groups, did not detail what they asked the agencies to do about 1,3-D.

At the hearing, Renee Pinel spoke on behalf of the Western Plant Health Association, which represents crop protection companies and was among the groups that hired lobbyists to influence state officials. “California already has the most conservative regulatory safeguards in the country for the use of 1,3-D to protect workers in the community,” Pinel said. “We ask that DPR continue to work with agriculture on including flexible application systems and techniques to make sure that these products are available.”

Californians for Pesticide Reform, though it represents more than 90 organizations to reduce pesticide use in the state, did not hire lobbyists to influence regulators. They resorted to other means to capture regulators’ attention.

A clearly frustrated Weller told DPR officials at the hearing that if they won’t ban 1,3-D, they should at least rewrite their regulations to ensure that no Californian is exposed to more than the most health-protective level. Then he said, “No justice? No peace!” and dropped to the floor to play dead.

For the next half hour, protesters continued chanting, drowning out the last speakers, even those who called on regulators to ban 1,3-D, in a hearing community members called “rigged.”

“DPR and OEHHA appreciate the engagement from the public in the regulatory process,” DPR’s Bailey said, referring to the crowd’s comments and angry protest. “This engagement will inform protections for occupational bystanders against potential 1,3-D exposure.”

The overwhelming majority of people at the hearing have little faith that their participation will change anything.

Before the hearing devolved into chaos, an organizer for Greenpeace chided regulators for treating farmworkers as disposable populations. “You should want to provide sanctuary from harm to the people who feed you,” said Ana Rosa Rizo-Centino, who previously worked for years with the United Farm Workers.

“I have come to so many of these hearings, and it’s always the same. We have to beg for the validity, for the dignity of our lives,” she said. “That is not OK.”

Note: Friday, Jan. 24 is the last day to submit comments to the Department of Pesticide Regulation about its proposed occupational bystander rule for 1,3-D. Comments can be emailed to the agency at [email protected].

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,