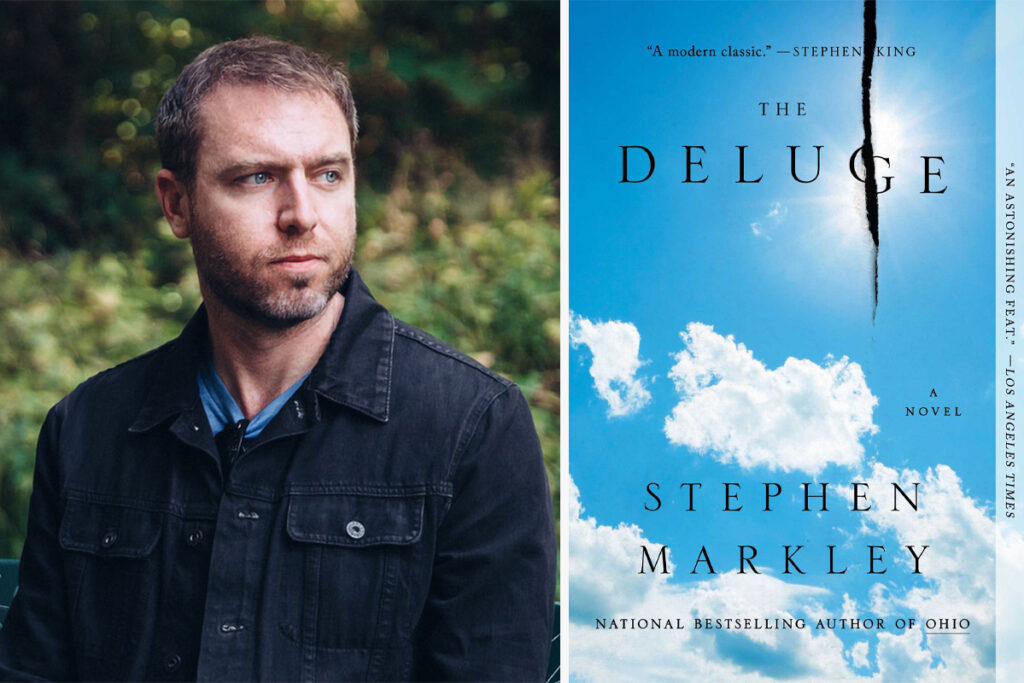

Bestselling novelist Stephen Markley’s 2023 epic, “The Deluge,” follows the climate crisis, extreme politics and societal decline in the United States from the years 2013 to 2039 through the eyes of everyone from a climate scientist to a drug addict, an advertising savant and a network of eco-terrorists. But its most cinematically dramatic chapter describes a wildfire destroying Los Angeles in 2031.

This month, Markley, who spent more than a year researching how wildfires could grow into an urban firestorm that overtakes Los Angeles, has watched the conflagrations burning into the city from his home there.

“I don’t think this is the worst fire I’m going to live through in my time living in Los Angeles,” he says. “The conditions that created this inferno, these two firestorms, they’re not going anywhere and in fact they’re going to get worse. And so treating this as like a one off, a random act of God, is really the wrong way to think of it. The city has to be preparing for when this happens again.”

Inside Climate News spoke to Markley about how the current fires compare to the disaster he imagined, and the parallels he sees between the climate-challenged world of his novel and the developments in the United States since his book was published. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MICHAEL KODAS: Does the current fire situation in LA feel like a bad dream you imagined coming true?

STEPHEN MARKLEY: What’s just so crazy about this is that there’s no clairvoyance on my part. I just looked at the science, looked at Los Angeles and sort of said to myself, “Well, if these conditions persist and get worse as the climate crisis progresses, it’ll happen eventually.” And then exactly that set of conditions that I wrote into the book was what caused these fires: two years of way above average, near record-breaking precipitation followed by a super dry year—you know, we haven’t had basically any rain in the rainy season—and then suddenly the Santa Ana winds. With all that dry vegetation, it’s just a powder keg.

KODAS: Your book forecasts climate change driving all kinds of environmental disasters, societal collapse, disintegrations of democracy. What struck you about the current fires in LA as most in keeping with the urban fire storm that you imagined?

MARKLEY: I think that the scariest one is the fact that in the book, this enormous fire happens and wipes out LA and yet life goes on as normal and people write it off as another catastrophe. It’s a human interest story more than it is a climate story, and I hate to say this, but I feel like, outside of outlets like yours, that’s exactly what’s happening. People somehow managed to talk about this without mentioning the climate crisis, the underlying basis for all of our catastrophic weather events.

You can already feel this having happened to Hurricane Helene. This record-setting, staggering storm that wipes a whole city in North Carolina basically to rubble, and it might as well be the war of 1812 in terms of press coverage and general public interest now. We’re anesthetizing ourselves, or maybe narcotizing ourselves, to what’s going on by again focusing on, “What an act of God … How did the mayor let us down?” All these little prescribed news stories distract us from the larger story of, this is what greenhouse gas emissions are doing to our planet and it’s only going to get worse.

KODAS: Are there other details that you included in your descriptions of the LA firestorm that you have seen turn out to be significant drivers of the current fires?

MARKLEY: I forget how much building into the [wildland urban interface] is a big problem all over California, and across the West, really. Housing is so tight here, people are continuing to build into more and more dangerous areas. Certainly, that’s the story of the Paradise fire a few years back.

You have a situation where, when housing prices in major cities are so high, people are going to keep spreading out into areas that are prone to wildfires. We remove some 5,000 structures from Los Angeles, and the housing problem here is already a nightmare, and that’s just going to get even more intense.

KODAS: What has surprised you the most about the current fires, given that a lot of this was predictable?

MARKLEY: Here’s the weird part: None of it has surprised me, and yet it’s still so shocking. Texting with a friend who has lost his home. His mom lost her home. His brother lost his home. They were all in the same neighborhood. I didn’t know what to say to this person, except “I’m so sorry.” That sensation of, “Oh, this is all real.” This is now in my hometown. It’s affecting people I know. It’s so difficult to wrap one’s mind around it. Unlike a lot of people who are seeing this as a once in a lifetime, a 9/11, I see it like we’re just getting started, like this is a warm-up act to all the climate catastrophes that are building in the system.

KODAS: In your book, the fire brings together a famous climate scientist with the homeless, the addicted, a wealthy entrepreneur and inmate firefighters, all of whom must change their own plans and relationships and cooperate to save lives and try to survive in the burning city. How do you see society and relationships changing now in the city and the nation?

MARKLEY: You see that in the immediate reaction. These donation centers here are just overflowing with stuff, with clothes and toiletries and bottled water and food, and all the restaurants serving people, all the drivers doing rides for people out of evacuation zones. You see the surge of people wanting to help and you see their better natures rise to the surface. The number of people who are doing that work, all that sort of camaraderie, the volunteer effort, it’s incredible to see.

That’s a short-term phenomenon. What I think a lot of us in the climate movement are searching for is, “OK, let’s think about the next level up. Let’s think about the long-term.” Can we get some of this housing stock zoned so you can build multi-family units so these regions aren’t just big mansions sitting alone by themselves? Can we actually improve the housing stock out of this crisis?

A new administration is coming in. We must defend the Inflation Reduction Act. We have to make the one-plus-one-equals-two connection of the most important climate bill ever passed and what just happened in Los Angeles. Will California, itself already a mover on decarbonization, put its foot to the pedal? Will Los Angeles put its foot to the pedal in figuring out how to decarbonize quicker? We have to make those connections and think about this catastrophe in the context of the wider crisis.

“I see it like we’re just getting started, like this is a warm-up act to all the climate catastrophes that are building in the system.”

KODAS: For decades, the media has focused on LA-area wildfires’ impacts on celebrities and the arts. Your book briefly describes a rapper saving his wardrobe. How does the fire burning into a community where the wealthiest and the celebrities are intermixed with a large unhoused population and people living below the poverty line affect the disaster’s impacts?

MARKLEY: This is a little too Pollyannaish, but seeing how the fire has impacted millionaires, basically, like TV stars [and] musicians, but also the historically Black community Altadena and everyone in between, it’s sort of like this touched everyone in the city, one way or another, even if you didn’t live there in these [directly impacted] neighborhoods. Everyone is staring at the same thundercloud of smoke.

I don’t know if this is just my immediate experience of it, of people saying, “Yeah, we know the focus is on celebrities’ houses burning down—but look at these working-class people, Teamsters, people in the film industry who do the dirty work, they also lost everything and it’s not as simple for them.” I hope it’s been a little flattening in terms of how we think of who can be affected by these big destructive events.

KODAS: What questions do the current fires raise for you that you hadn’t considered before?

MARKLEY: It’s not that I haven’t considered this before, it’s that I didn’t consider it would happen this fast, which is the effect of not just the fires but all these disasters on the insurance market and what’s happening to home insurance across the country. This is how my novel ends, with a major financial crisis being sparked by a collapse of the insurance market, basically.

Insurers are already fleeing California in droves. It’s getting so difficult to insure houses in wildfire zones. Who is going to insure these rebuilt homes in the Palisades and Altadena and really anywhere in the [wildland urban interface] where a fire is possible?

Then you look at all the storms coming. These storms that start as hurricanes in the Gulf, but then become these super rain events in the interior of the country. A lot of people who died in North Carolina were in regions that had never seen flooding before. Then you look at the Midwest, where it’s hail damage and storm damage. Increasingly, there aren’t many regions of the country where property is clearly insurable because climate change, the climate crisis, basically destroys the models for risk. I think this is a burgeoning crisis that is not getting enough attention and I’m really nervous to see what happens with insurance in California after this.

KODAS: AI and tech play roles in your book, as do changes to the U.S. government, the functioning of democracy and all kinds of economic fallout and trickle downs. What are you seeing now around the interplay of technology, democracy and disasters?

MARKLEY: That element of “The Deluge” is a primary part of it, but the reality is actually so much worse, particularly with the prevalence of AI and what it’s able to produce, and what people are able to produce so easily. This is just a total mess and it’s so hard to figure out how society will extricate itself from basically a post-truth world where no facts matter.

Some of the stuff being said, you’re like, “Dude, I’m living here. There are no tanks on the street.” How do you contest this stuff? It’s so frustrating and certainly I have a long-standing critique of Silicon Valley and surveillance capitalism, what it’s done to the discourse and what it’s done to democracy, and none of it’s good.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowKODAS: It is interesting to me that a fiction writer who has written about a post-apocalyptic hellscape in Los Angeles as it burns in a wildfire is having to stand up to fictions presented about a post-apocalyptic hellscape in Los Angeles during wildfires.

MARKLEY: I’m not going to say that there aren’t incredibly useful ways to put AI to work, including material science and medicine. There’s a lot of potentially revolutionary stuff coming out of that. But also it’s going to make our misinformation hellscape exponentially worse without some serious thought and regulation.

The floodgates are opening right now and we’re driving straight into this with no thoughtfulness whatsoever. The self-anointed tech gods of the neoliberal order are just like, “Yeah, we’ll just build data centers hoovering up energy as fast as possible to write emails for people, and we’ll scrape novelists’ books and we’ll feed in screenplays and … create content for people without a human being ever actually touching it.” It’s hard for even the most imaginative novelists to wrap their heads around what the potential downsides could be.

KODAS: Until the last few years, any book that included a climate disaster seemed to be relegated to the genre of science fiction. Do you see things happening now, disasters that might be seen in a Hollywood blockbuster, as pushing works of fiction like your book away being labeled dystopian fantasies and more toward a recognition that these are all possible results of the situation that we find ourselves in?

MARKLEY: I did not make this up, but heard it somewhere—“The only science fiction coming out right now are all these shows, movies, books [and] novels that don’t include the climate crisis—that’s the science fiction.” Because it is impacting our world and our day-to-day lives so routinely and so aggressively, you really have to … close your eyes, cover your ears and speak no evil, as well, to ignore it.

I started to become very irritated when people would refer to “The Deluge” as dystopian or apocalyptic, because it puts it in the same genre as “The Hunger Games” or some other sort of fantasy novel, and “The Deluge” is a realist novel. It was about what we are going to live through, and now it’s just about what we are living through.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,