Farmland is everywhere in tiny Unity Township, from neat fields of corn to open cattle pastures. And so are layers of wet organic sludge, a onetime fertilizer that has triggered a crisis over “forever chemicals” in central Maine and how best to rid the land of the poisons.

Farmers relied on sludge from local wastewater treatment plants for years to support their crops and improve yields. Unity Township, a farming community home to less than 50 people, now has some of the highest concentrations of PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, on agricultural land anywhere in Maine.

Three years ago, Maine was the first state in the nation to recognize the risks of PFAS—manmade chemicals linked to cancer, birth defects and other dire health problems—by outlawing the use of sewage sludge on farmland. But PFAS, testing showed, had already seeped into drinking-water wells and crop roots, tainting vegetables, beef and milk.

Research about PFAS is sobering and so are the concerns of people in this northern state who have worked and lived with them—and testified to state legislators about the high rates of contamination at their farming businesses and in their bodies.

“We have farmers in Maine who have more PFAS in their blood than the factory workers in the 3M plants [that produce PFAS], because we eat it, we drink it, we live it,” said Bill Pluecker, the public policy organizer at the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA).

The demand to ban sludge as a fertilizer has been hailed as an environmental corrective, but there are no easy fixes to the PFAS dilemma. Lawmakers and state regulators have yet to figure out, in two years of consultations, a long-term solution for truckloads of sludge still being produced at wastewater treatment facilities and sent to landfills.

The problem? There isn’t enough landfill space for all the sludge that Maine now has to dump.

PFAS are a dilemma across the United States. They have been used since the 1940s in all sorts of household products–including nonstick cookware and waterproof fabrics–and they do not break down easily in the environment. Connecticut instituted its own sludge application ban in 2024, and Minnesota and Michigan have limits on its use as fertilizer. Several other states’ legislatures have considered partial or full bans on sludge application since Maine’s ban.

Maine officials and waste management companies are experimenting with different methods to degrade PFAS chemicals and reduce the space that sludge occupies in landfills. They simply can’t work fast enough, said environmental advocates who are sympathetic but anxious for results.

“When we think about policy change around PFAS in commercial products and our waste stream, we tend to focus on economic impacts,” said Adam Nordell, a farmer who had to close his operations a few years ago over high PFAS contamination and who now advocates about farmland contamination risks. “But at the end of the day, it’s a story about human health.”

Tainted Soil

Maine’s revelations started with a single dairy farm in the southern part of the state, after tests of a water well there revealed high levels of PFAS. Subsequent tests of the milk produced on the farm in 2016 uncovered high levels of PFAS and set off alarms.

The state created a PFAS task force and set its own safety standards for concentrations in milk, beef and drinking water. By 2020, contaminated milk was found at two more dairies, and the next year the Maine legislature required that the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) by 2025 test for PFAS at all sites that had used sludge.

In 2019, the first contaminated dairy farm, after being in business more than a century, was forced to close because it was unable to get its PFAS levels low enough to meet state standards.

Applying wastewater sludge as an agricultural fertilizer was considered “beneficial” starting in the 1970s, but then farmers didn’t know that PFAS was washing out of factories and homes and accumulating in the sludge that wastewater treatment facilities produced.

In the early 2000s, about 80 percent of Maine’s biosolid waste was used in compost or applied to farmland. By 2022, when the sludge ban was approved, that percentage had fallen to 40 percent.

Just what is considered safe depends on federal or state agencies’ limits, and different compounds in the PFAS “family” have different recommended levels. In drinking water, the safe level is microscopic: just a handful of parts per trillion. Soil limits are higher, since soil doesn’t directly expose people to the chemicals.

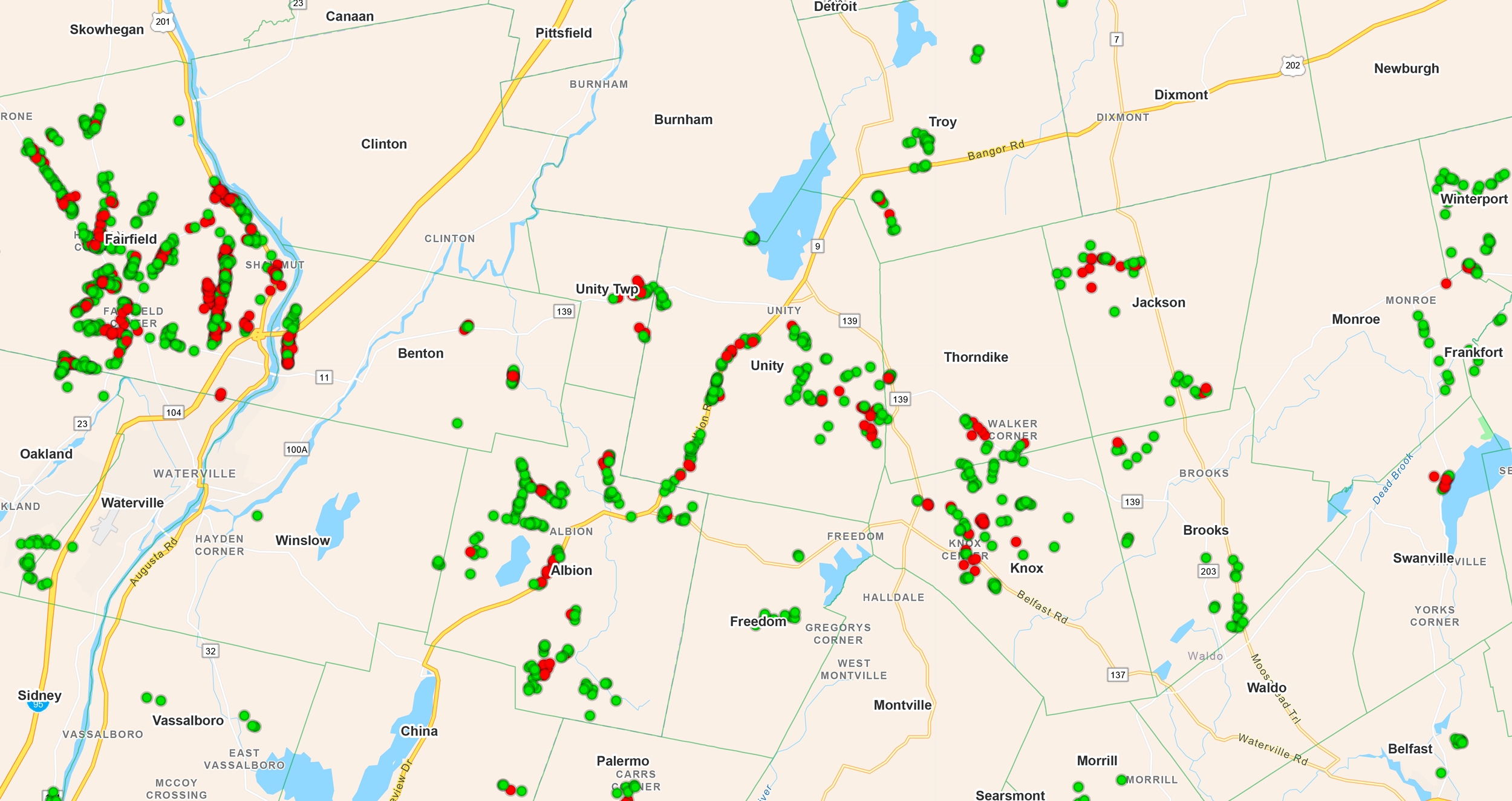

Maine’s DEP started its testing program by contacting about 700 properties that had a history of sludge use and prioritizing its review by how much sludge had been applied at each property. The list eventually included more than 1,000 farms of 7,000 total across the state, and the DEP has extended its testing deadline to 2029.

As of this year, DEP has identified more than 90 farms with unsafe PFAS concentrations, and many of the high-contamination properties are clustered in central and southern Maine farming communities like Unity Township.

Some farmers whose fields were contaminated were able to pursue ways to lower PFAS levels. That included adding carbon filters to irrigation water, changing cattle feed or just growing different crops that did not absorb as much PFAS from the soil.

But some farms could not adjust. Decades of sludge use had turned their fields into hazards.

“The problem of waste is a big problem for our society as a whole to grapple with. It’s not fair to foist that problem on farmers,” said Nordell, the farmer-turned-advocate who is the campaign manager for farmland contamination for the nonprofit Defend Our Health.

Nordell was one of the farmers most affected by PFAS, and his lost land is now contributing to the science that may help tame PFAS contamination. After his business shuttered in 2021, his farmland near Unity Township was bought by the nonprofit Maine Farmland Trust for agricultural and PFAS research. The state has purchased other contaminated farms to consider how best to use them.

Nordell said low-income families in Unity Township who hunt or fish for sustenance are impacted too, since PFAS has been found in the area’s fish, deer and turkeys. The township has issued an advisory to avoid consuming wild game from the area.

“It’s one of the very worst PFAS-impacted sites in Maine, without a question,” Nordell said.

Relief Efforts

In the early days of PFAS testing, many affected farmers were just trying to survive and cope with the threat to their livelihoods, said Pluecker, of the organic farmer association.

The state instituted a relief fund for farmers, as did the organic farmers group which goes by the acronym MOFGA. Money was allocated for blood testing, water filtration, infrastructure upgrades and mental health support. The fund also helped supplement lost income.

“In the beginning, we were just focused on helping keep farmers solvent,” said Pluecker, who is also a state House representative.

Pluecker said the focus now is how to proceed with the cleanup. As of 2025, the state relief fund has allocated more than $2 million in farm relief and $3 million in research grants. At the federal level, Sen. Susan Collins and U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree have sought to add PFAS relief to the U.S. Farm Bill, which funds agricultural and food programs, including farm income support, food assistance, conservation, trade and rural development. So far, the lawmakers have been unsuccessful.

But the story of PFAS in Maine is a long and seemingly never-ending tale of woe. The more the state tests for these chemicals, the more contaminated sites it finds.

Elevated PFAS levels have been found in tests of game animals and river and stream sites. PFAS is in wastewater discharge and landfill leachate. A DEP study in 2023 sampled leachate from 25 landfill facilities in Maine and found that all had concentrations of at least five different PFAS chemicals, and most landfill facilities had 16 or more types in their systems. But that study only tested the systems that catch runoff, not the surrounding soil or water.

DEP Deputy Commissioner David Madore said landfill sites aren’t obligated to monitor for PFAS chemicals in groundwater. Maine authorities, however, can require testing if the state suspects a private well may be at risk of contamination.

The possibility of PFAS escaping containment through runoff or through a failure of a landfill’s control systems looms over communities near these sites, Nordell said.

The DEP has so far identified nearly 800 private wells that exceed Maine’s drinking-water standard. If the state adopted the tougher federal standard, the total of contaminated wells would be higher, Nordell said.

“Those societal costs are borne by the individual in a very unjust way,” he said.

PFAS continues to be a major concern for the state legislature.

In the past two sessions, lawmakers voted to set contamination limits on Maine farm products, expand the well-water testing program, require landlords to test for PFAS and disclose results to tenants, and create a state program to dispose of firefighting foam, which contains high levels of PFAS.

A bill requiring health insurance companies to cover the costs of PFAS blood testing was carried over during the most recent legislative session.

Maine is offering free blood tests to more than 600 exposed families, and it has installed around 500 filtration systems in private wells that exceeded the drinking-water standards.

Waste Crunch

Wastewater and landfill facilities are “always out of sight, out of mind in any community,” said Dan Marks, superintendent of the Falmouth Wastewater Department in southern Maine. But when the 2022 ban on sludge application went into effect, sewage plants and dumps were suddenly in the spotlight.

Sludge can’t just be sent straight into any landfill. It first has to be combined with bulky dry material to make it stable–and then only certain facilities can take biosolids, Marks said.

Casella Waste Systems, which runs a state-owned landfill known as Juniper Ridge, balked at the lawmaker’s ban both before and after it was implemented. State lawmakers voted to ban sludge use on farmland as well as imports of out-of-state waste in the 2022 legislation.

Casella called foul, claiming it could not handle a sudden uptick in Maine’s sludge waste without taking in loads of bulky waste material from out of state. The out-of-state material was needed to stabilize the added sludge, it said.

The sludge ban went into force at the beginning of 2023. By February, Casella stopped accepting sludge disposal at Juniper Ridge. Wastewater facilities around the state were stuck with truckloads of sludge and nowhere to put it. At one point, thousands of tons of the state’s sludge were trucked northward into Canada for disposal and put Maine’s PFAS efforts in the headlines for less-than-ideal reasons.

By July, the legislature passed an emergency bill that postponed its ban on out-of-state waste, and Casella announced that Juniper Ridge would begin accepting sludge again.

But sludge disposal remains a mess for the state’s PFAS containment efforts.

Handling sludge has gotten more expensive and more complicated since 2022, said Scott Firmin, general manager for the Portland Water District. Once, trucks from Portland’s wastewater facility could arrive at the landfill around the clock, any day of the week.

Now, the landfill has to ensure that there’s ready bulking material when the sludge arrives to avoid odor issues. Firmin said his department’s trucks are limited to a seven-hour disposal window, six days a week.

The Portland Water District serves 56,000 households and businesses in Maine’s largest city and surrounding municipalities. If trucks miss their landfill times, Firmin said, the district has problems.

“Our flows never stop, so it’s not like we can take two weeks off and wait for things to be solved,” he said.

The Lewiston-Auburn Clean Water Authority, the state’s second-largest treatment facility that serves 35,000 households as well as septic waste from 26 surrounding communities, said on its website that losing the ability to send sludge to farm fields has been costly. Trucking sludge to a landfill means spending $400,000 more a year in landfill costs, the website posting said.

“Not a Sustainable Solution”

The state DEP too has warned that there have to be other solutions for sludge disposal. There “could be a drastic shortfall in capacity” as soon as 2028 without significant action, according to a DEP report issued in December 2023.

Marks of the Falmouth Wastewater Department said sludge disposal in landfills requires four times its volume in bulking material.

That’s a problem. Juniper Ridge Landfill has seen a 15 percent increase in monthly sludge disposal amounts since the sludge ban, according to Jeff Weld, a Casella company spokesman. The overall amount of garbage Maine throws away has increased as well since 2017, according to state data. And, more worrying, Juniper Ridge is projected to be full by 2028.

Casella has applied for a 61-acre expansion to the Juniper Ridge Landfill, which would extend its lifespan by 11 years. However, environmental advocates and the Penobscot Nation, whose members live downstream from the landfill, are suing to stop that project on the grounds that it would bring the landfill closer to their community and worsen the existing air and water pollution.

Marks said the state is facing “unintended consequences” by not finding better ways to cope with its PFAS-contaminated waste.

“All we’re really doing with this model…is accumulating PFAS in the wastewater cycle, and that’s not really a long-term solution,” Marks said. He noted that landfills are not easily approved for expansion because no one wants to live near one.

“The landfill is not a sustainable solution,” Marks said.

Technologies to Tackle Sludge

Drying out wastewater sludge may be one way of containing the problem, or at least slowing it down. Removing water will not diminish PFAS but it can significantly decrease the amount of sludge. Drying makes the waste material more stable and greatly reduces the amount of bulking material needed for the landfill, Marks said.

Portland Water District is looking at ways to upgrade its dewatering systems for faster wastewater processing, at a cost of about $12 million, Firmin said. The district is also considering adding a sludge-drying facility. A 2023 study projected a drying facility would cost between $40 million and $103 million, depending on where it’s built and the type of drying technology used.

The PWD currently sends 17 dump trucks per week to the landfill, Firmin said. Upgrading the dewatering equipment would reduce that number to 14 trucks per week. With a drying facility, he believes the volume would drop to only four trucks per week.

Another site, the Crossroads Landfill, run by Waste Management & Recycling Services, in the town of Norridgewock is building a sludge dryer that is expected to begin operations in early 2026 and could process as much as 83 percent of the state’s sludge, or more than 70,000 wet-tons per year.

Crossroads did not agree to an interview but supplied a factsheet with some details about its planned $37 million facility. The dryer will be able to process 200 tons of biosolids per day that will result in 50 pounds of dried solids that can be sent to an onsite landfill, the Crossroads factsheet said.

Firmin said investing in drying improvements is likely exchanging one cost for another. The fees for transporting and disposing wet waste are rising, he said, so customers’ wastewater rates would probably increase with or without the upgrades.

“I think we’re going to end up paying more money, but we’re going to get out of the crisis mode we’re in right now,” Firmin said.

Destructive Technologies

The technology to break down PFAS chemicals is still being developed, and several facilities in Maine are experimenting with different methods of degrading the contamination.

“There really is a race at this point to get something to market,” said Marks of the Falmouth Wastewater Department. The ban on sludge, although hard on wastewater plants, is driving innovation, he said.

Most methods to destroy PFAS involve using high temperatures, pressure or incineration, in a controlled environment to prevent the PFAS from entering the air as an aerosol. These processes can create usable byproducts like biogas or biochar.

Other technologies don’t destroy the chemicals but filter them out of the waste and condense them into a separate product to be disposed of.

Over the summer, Juniper Ridge tested two pilot projects for removing PFAS chemicals from the landfill’s leachate, through a technology that essentially “bubbles” out the PFAS from the rest of the waste.

In October, Casella announced its plans to install a complete PFAS leachate treatment system by 2027, which is part of the state’s requirements for approving Juniper Ridge’s expansion.

The Crossroads landfill is also putting in a PFAS treatment system, which will treat the liquid created by the sludge-drying process and the landfill’s leachate, according to a Waste Management factsheet.

Another central Maine wastewater district, serving the towns of Anson and Madison, has plans for a regional facility, estimated to cost $31 million, to remove PFAS from sludge. The project has been in development for three years and is still seeking funding sources.

“There are these examples of wastewater facilities and landfills that appear to be acting responsibly, so it can be done,” Nordell said, referring to the Anson-Madison and Crossroads projects.

A private company called Aries is planning to build a PFAS pyrolysis facility in the city of Sanford, between Portland and the New Hampshire border. The plant would break down PFAS and turn the dried sludge into biochar. There is some skepticism of the plan: pyrolysis has barely been used at a commercial scale, so its reliability is uncertain.

Aries aims for operations to begin in late 2027. The company did not respond to interview requests.

The Portland Water District is also considering the addition of pyrolysis technology to its future drying facility, which would cost an estimated $54 million. Firmin said he isn’t completely assured of the technology’s ability to handle a large city’s wastewater volume and to remove enough PFAS to reach safe levels.

The Falmouth Wastewater Department, where Marks works, serves around 3,400 households and businesses. Investing in a technology like pyrolysis wouldn’t make sense for a small department like that, Marks said, especially when it already has to pay millions of dollars to replace aging equipment and address climate resilience.

Falmouth would have to partner with other municipalities to buy that equipment, or try to use the facilities of nearby larger departments like Portland, Marks said.

Portland produces about 20 times as much sludge as Falmouth, “so it makes sense for me to hop on board with whatever they’re doing,” he said.

If Portland Water District adds pyrolysis to its sludge-drying facility, Firmin said the district’s 17 trucks per week of sludge waste would be replaced with about half a truck a week of dried material.

“If we had half a truck a week of biochar, that could very likely be very easily landfilled,” he said.

Still, the drawbacks of these technologies mean that they won’t be the silver bullet for Maine’s sludge problem. By the time these technologies are ready for widespread use, “we’ll have used up a lot of our remaining landfill capacity, so do we want to wait?” Marks said.

The Costs of “Zero”

One option to relieve Maine’s landfill pressure, Marks said, is allowing land application again if the sludge is below a certain PFAS contamination level, as Michigan has done.

Waste from paper mills and other PFAS-using industries, for instance, is going to be far more contaminated than waste from homes, he said.

“Trying to figure out a policy that lets us get back to some sort of beneficial reuse, of low levels of risk, to me makes sense,” Marks said. “One blanket ban didn’t seem to wrestle with it all.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowHowever, farming advocates oppose a partial repeal.

“What we know about PFAS in our wastewater stream, and what we know about the history of land application and the cumulative impact of that, should give anyone pause about returning to land application,” Nordell said.

Laura Orlando, a senior scientist with the national nonprofit Just Zero, said there is no justification for using sludge again when it comes to PFAS considerations. There is no safe amount of exposure in food or water, she said.

“There is no safe level, so to back off on the total ban that Maine has to relieve pressure on landfills is to say we’re going to do that by sacrificing Maine’s soil, by sacrificing Maine’s food, by sacrificing people’s health,” she said.

Marks said a PFAS-free environment isn’t feasible in a world with decades of past contamination and the continued production of new PFAS chemicals.

“I have little kids. That’s what I want too. And what we see when we’re at the wastewater plant is that’s really not possible. We live in a contaminated environment,” Marks said.

“We have to deal with our consumption. We can’t keep living the same kind of lifestyles that we’ve become accustomed to. Nobody wants to say that, but it’s the reality,” Marks said.

Upstream Sources

The Maine state legislature passed laws in 2021 and 2023 that required companies to phase out the use of PFAS for many consumer products in a series of staggered deadlines through 2040. The first deadline, in 2023, applied to carpets, rugs and fabric treatments.

On Jan. 1 of next year, the phase-out will extend to products including cookware, cleaning products, floss, ski wax, kids’ toys, menstrual supplies, upholstered furniture and certain outdoor wear.

“It’s turned off the tap on contamination, so it’s stopped a very expensive, pressing problem,” Nordell said, though it doesn’t address the contaminants already released.

Maine has already set aside more than $60 million for agricultural PFAS testing and cleanup, and Pluecker said remediating its water would likely cost billions more dollars over time.

The Trump administration is unraveling more stringent EPA guidelines on PFAS contamination, but Maine will continue to follow its own standards, advocates for the cleanup said.

Nordell said the way that Maine and other states approach PFAS contamination now will help define how other risks–in the ground, air, and water–can be contained in the future.

“This isn’t a story about two chemicals. This is a story about everything we don’t know about our waste stream,” he said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,