Eighteen-year-old Danny Nolasco spent the day of July 15, 2024, mixing and hauling buckets of cement at a construction site in stifling heat.

The neighborhood of sprawling four- and five-bedroom houses, west of the Austin suburb of Bee Cave, was worlds away from the small mountain town in Honduras where Nolasco grew up. He had come to Texas two years earlier, hoping for a better life, and was working in his free time while attending school.

The crew started work at 9 a.m. and plowed through the day, breaking only once, for lunch. By the afternoon the temperature had reached 99 degrees, with a heat index of 104.

Shortly after 6 p.m., Nolasco collapsed. Other workers called 911 but when emergency medical providers arrived, they were not able to revive him. He died on the scene.

“It all happened so fast,” said Grevin Hernández, Nolasco’s uncle. “We never got a clear explanation of what happened to him.”

The Travis County medical examiner listed his cause of death as “undetermined” and found no underlying health issues.

But U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration investigators, who look for underlying causes of workplace casualties that might otherwise go unnoticed, classified the fatality as a heat death. They found that Nolasco’s employer did not sufficiently prepare him to work in high heat.

Carlos Cruz Construction, the company he was working for that day, declined to comment for this story.

About This Story

This is the fourth in an occasional series of stories exploring the effects of rising temperatures across Texas. The project is a collaboration between Inside Climate News, the San Antonio Express-News and Public Health Watch.

As hot weather reaches new extremes and heat deaths rise across Texas, more workers face the same risks as Nolasco. Inside Climate News obtained OSHA records detailing five other Texas workers who died from the heat in 2024. From the Panhandle to San Antonio to Houston, construction workers, an oilfield worker and a mechanic all succumbed to punishing temperatures.

Nolasco was the youngest; the oldest was 57. All were male; none was a union member. Two were Central American immigrants. In three of the six cases, OSHA fined the employer for failing to protect workers from heat. One family filed a wrongful-death lawsuit.

Recent research shows that statewide heat safety standards can help prevent injuries. But despite its withering climate, Texas, like most states, has no regulations requiring water breaks or other worker heat protections. Bills in the Texas Legislature aiming to create statewide workplace heat standards and worker protections have failed.

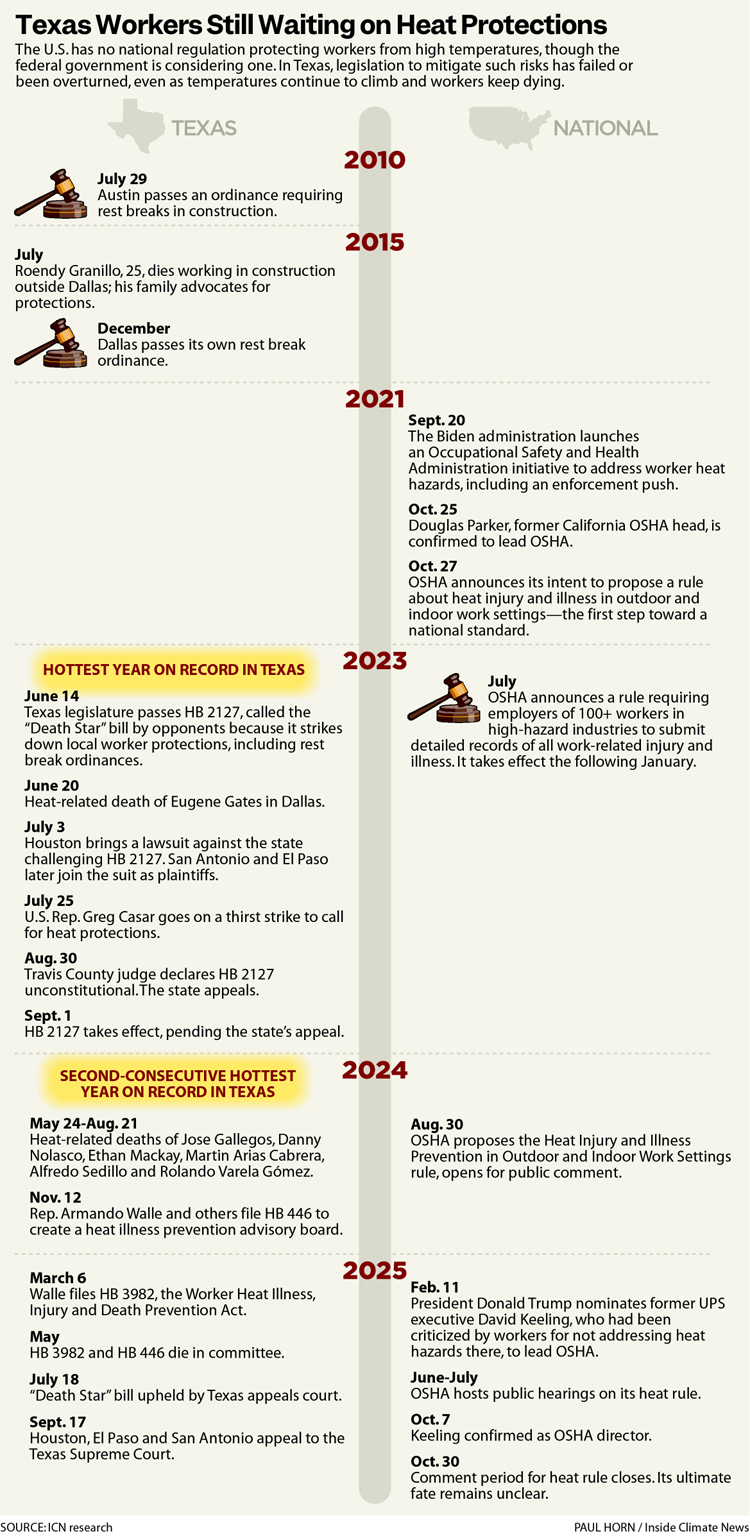

Austin and Dallas ordinances required rest breaks for workers within city limits. But in 2023, they were overturned by House Bill 2127, dubbed the Death Star bill by its opponents. The bill banned city ordinances governing commerce, including any labor protections, and effectively blocked other cities from passing similar protections.

Meanwhile, workers keep dying preventable deaths. Many of these, experts warn, go unrecorded—hiding the true extent of the crisis.

Growing up in Sabana de Suárez, Honduras, Nolasco was active in the local Catholic church, San Miguel Arcángel. Grevin Hernández, who was only three years older than his nephew, told Inside Climate News in a phone interview that they were more like brothers.

Nolasco’s family, devastated by his death, repatriated the teenager’s remains to Honduras. A funeral was held in August 2024.

“We still haven’t really adjusted to the fact that we lost my nephew,” Hernández said. Nolasco’s parents and grandmother, he added, are struggling with the loss.

“It’s been very complicated for them,” he said. “It’s hard for them to talk about this.”

The U.S. requires safe workplaces but has no national regulations specifying how to protect workers from heat. Last year—a half-century after a federal research agency made recommendations for such protections—the Biden administration introduced a draft of what could become the first federal heat safety rule, requiring employers to address heat hazards in the workplace.

It’s unclear what will become of the proposal under the Trump administration, which is rolling back regulations across the government. OSHA began public hearings on the proposed rule in June, a month after House Republicans attacked it in a congressional hearing.

Heat is the No. 1 weather-related killer worldwide; the International Labour Organization—a United Nations agency—estimated that more than 2.4 billion workers were exposed to excessive heat globally in 2020. Local and national governments have failed to catch up to the risk, which climate change is worsening.

Only seven states in the U.S. have any kind of workplace heat standard, and even those only cover some industries or types of workers. Other states, including New Mexico and Arizona, are developing standards.

“Without proper protections for these workers, we’ll see more workers either get hospitalized or unfortunately not come home to their families at the end of the shift,” said Texas state Rep. Armando Walle, a Democrat from Houston.

Labor advocates and some elected officials in Texas, like Walle, are continuing to fight for heat protections for workers. It’s an uphill battle.

Walle introduced a bill for worker heat protections in the state’s 2025 legislative session, proposing basic interventions, backed by research, such as mandated heat safety training, paid rest breaks, shaded rest areas and access to drinking water. The bill didn’t even get a hearing, let alone reach the floor for a vote.

“Those people are on my mind all the time,” he said. “Every year I file these bills and I will continue to fight for these workers.”

Six Lives Cut Short

The first heat fatality that OSHA investigated in Texas in 2024 was of a 51-year-old oilfield worker. Jose Gallegos died on May 24 while working on a rig in South Texas. He was pulling pipe under full sunlight, on a day with a high of 101 and a heat index peaking at 114.

Nolasco collapsed and died in July of that year. Less than one month later, 21-year-old Ethan Mackay died while installing fences in the small Panhandle town of Girard.

Then the biggest heat wave of the year hit Houston and San Antonio. On Aug. 19, Martin Arias Cabrera died while installing fences at a Houston house. Two hundred miles west, Alfredo Sedillo, 43, died the next day after a shift at a nursery in San Antonio. On Aug. 21, Rolando Varela Gómez died in Fort Bend County, outside Houston, at the construction site of a water treatment plant.

Those six deaths are likely far from heat’s full toll that summer. The draft federal heat rule acknowledges “significant undercounting” of occupational injuries, illnesses and deaths. Last year the Tampa Bay Times found 19 heat fatalities among Florida workers between 2013 and 2023 that had not been reported to OSHA. Underreporting is especially prevalent in industries like construction that employ many undocumented immigrants.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 1,042 worker deaths due to occupational exposure to heat between 1992 and 2022—34 a year on average. One-third of those deaths were among construction workers, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA also notes this is likely an undercount.

OSHA investigations show how some employers fail to provide the most basic protections from heat. Other employers have heat safety plans but don’t always follow them.

Republican legislators in Texas have argued against worker safety protections on the basis that OSHA rules are sufficient. But the agency has long been understaffed. In 2020, the National Employment Law Project found that it would take the agency 165 years to inspect every workplace under its jurisdiction a single time.

Trump’s proposed 2026 budget would slash OSHA’s funding by nearly $50 million, including major cuts to its enforcement division, and would eliminate more than 200 workers—about 12 percent of its staff.

Following the six workplace heat fatalities in Texas in 2024, OSHA issued penalties to four companies that ranged from under $5,000 to over $31,000. Some of the fines were for safety violations unrelated to heat that OSHA found while investigating the deaths. Two of the cases are still open.

This information reflects inspection reports OSHA released to Inside Climate News through public records requests and details on the agency’s website. OSHA answered a question about one company’s fines but did not answer other questions about these inspections.

Family members of deceased workers said they didn’t receive updates from OSHA about the results of the agency’s investigations into their relatives’ deaths.

Ryan Pollock, executive director of the Texas State Building and Construction Trades Council—a trade union—said OSHA is “intentionally underfunded.” The number of heat deaths, he added, does not reflect “the significantly larger amount of near-misses” at Texas construction sites.

Pollock, who previously worked for an electricians union, gave examples of seriously ill workers left to cool off under a tree or sent home from work without receiving proper medical care.

OSHA says employers should encourage workers to drink at least one cup of water every 20 minutes while working in the heat. For jobs lasting more than two hours, they should drink beverages with electrolytes, like sports drinks.

“Some people are shocked that we would have to make sure that cool water be provided on these worksites. But it’s shockingly necessary.”

— Ryan Pollock, Texas State Building and Construction Trades Council

The day Alfredo Sedillo died, he was repairing an excavator behind a flower shop. Altman Specialty Plants, his employer, did not provide water for him and his coworkers, according to OSHA documents. When investigators visited the site less than a week later, they found water fountains covered in dirt, trash and cobwebs with no running water. Where there was a shelf holding gallon-sized bottles of water, a sign warned: “Please do not use water for coffee. Water is for Toilet. Thank you.”

Pollock, of the building trades council, said the union contract for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 520 in Austin requires employers to provide cool water during warm weather. Access to water is not a given.

“Some people are shocked that we would have to make sure that cool water be provided on these worksites,” he said. “But it’s shockingly necessary.”

In an emailed statement, an Altman representative said the company provides ice machines, potable water, shade and rest breaks for employees, and trains both management and employees on heat-illness prevention.

“Our employees’ well-being is important to us,” the statement read. “We were deeply saddened to learn of Alfredo Sedillo’s passing, and our thoughts remain with his family and loved ones.”

A sign instructs employees not to drink water on a shelf and a water fountain covered in cobwebs, trash and dust are photographed by OSHA during an investigation of Altman Specialty Plants on Aug. 26, 2024, less than a week after Alfredo Sedillo’s death. Credit: OSHA

Francis Sedillo, Alfredo’s wife, said that he and his coworkers were exposed to extreme heat constantly at work, and every summer brought instances of heat illness. She remembers that the company’s ice machines were often broken and that he and his colleagues would sometimes have to buy their own ice to cope. She worried about his long hours and what she saw—and OSHA later cited in its investigation—as the company’s lack of heat protections. According to OSHA records, the company had at least three other recorded heat-related injuries.

Although Altman said it has a heat training program, OSHA found that at least some workers were not trained last year, and Francis Sedillo said that her husband was among them.

In the emailed statement, Altman wrote that the plant’s general manager spoke with Alfredo Sedillo before he left work for the final time and “there was nothing to suggest he was feeling unwell or in distress.”

“We cooperated fully with OSHA in its review, and the matter has since been resolved,” the statement continued.

The day that Alfredo Sedillo died was one of the hottest of the year there, hitting 105 degrees. When he got home from work that day, he felt dizzy and overheated. He went to take a shower as Francis Sedillo worked in the living room. After a while, she checked on him.

He was unconscious. She called an ambulance immediately, but it was too late.

“He was already gone,” she said.

Later that day, a justice of the peace arrived and ruled a heart attack the cause of death, although Alfredo Sedillo had no known heart problems, his wife said. No autopsy was performed, nor did anyone tell Francis Sedillo it was an option. Later, she sought legal advice and a lawyer told her that without an autopsy, there was nothing she could do to get justice for her husband’s death.

His employer did not report the death to OSHA within eight hours, as required by law, the agency said. It was Francis Sedillo who called the San Antonio OSHA office and prompted an investigation into hazardous workplace conditions.

The agency found that Altman, Alfredo Sedillo’s employer, had failed to protect him and his coworkers from extreme heat. OSHA issued the company multiple citations, ultimately fining it about $31,000, which the company paid.

Francis Sedillo fears another family will go through what she did.

Many of her husband’s coworkers were immigrants, elderly or with limited job options, making it difficult for them to advocate for safer conditions, she said.

“I need to speak up because my husband was born here and he has a voice,” she said.

Immigrants Face High Heat Risks

Many of the most physically demanding and dangerous jobs in Texas are filled by immigrants. This also makes them more vulnerable to the heat.

All workers can face retaliation for reporting unsafe conditions, but the stakes are even higher for immigrant workers, said David Chincanchan, Austin-based policy director of the advocacy group Workers Defense Project.

“It puts immigrant workers in a really difficult position,” Chincanchan said. “And the fact that immigrant workers are put in such a vulnerable position to be exploited doesn’t just impact the immigrant workers, it lowers the standards and the conditions for all workers in Texas.”

Cándido Álvarez, a Honduran immigrant, knows this firsthand. During a decade working in construction in Houston, he said, he has experienced wage theft and dangerous working conditions. To cope with the city’s brutal heat and sticky humidity, Álvarez starts drinking water well before reporting to work at 7 a.m. But by then, “sometimes you’re already sweating.” He sometimes sweats through three shirts in a single work day.

“When the hot season comes, it’s always an odyssey,” he said in Spanish.

Álvarez, a member of the Workers Defense Project, said that his current employer brings ample water to the worksite and makes sure everyone takes breaks. But he has worked for some project managers who don’t supply water and discourage even the shortest of breaks.

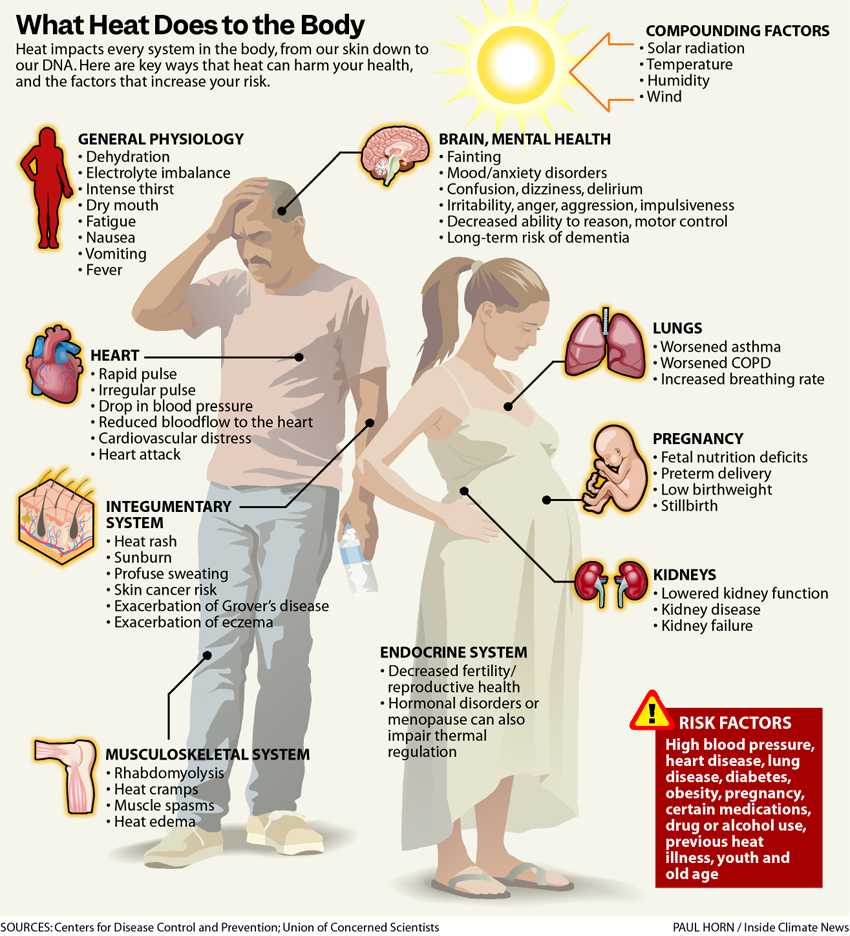

Álvarez worries that working so hard in the heat is doing damage to his kidneys—a fear increasingly backed up by research. But he said he can’t afford to take time off to see a doctor.

“If you don’t go to work, everything gets thrown out of balance. The bills don’t stop. The rent is still due,” he said. “It’s a crime to get sick.”

This year there’s even more pressure for immigrant workers to keep their heads down and endure dangerous working conditions. The Trump administration’s unprecedented, militant expansion of federal immigration enforcement agencies—including raids, detentions and targeting of both undocumented and documented immigrants and even U.S. citizens—has sowed panic among immigrants and their neighbors in communities across the country.

The Workers Defense Project and the University of Illinois Chicago surveyed 353 construction workers in Texas metropolitan areas in 2024. Half the workers reported they were undocumented.

Among the immigrants who died in the Texas heat last year was Rolando Varela Gómez. He first settled in Wisconsin when he came to the United States from Nicaragua, according to a relative who spoke with Inside Climate News by phone. But he struggled to find work and headed to Houston, where he’d heard that companies were hiring.

Varela Gómez joined a crew building a water treatment plant near the small town of Beasley, outside Houston. He had been working in Texas for only two weeks when he died on Aug. 21, 2024. His relative said that coming from “freezing” Wisconsin, he wasn’t used to the Texas heat.

According to the OSHA report, Varela Gómez and other workers were exposed to extreme heat while moving materials and equipment and pouring concrete. OSHA reported that he developed heat illness and died from acute kidney failure.

The family had to raise money to repatriate Varela Gómez to Nicaragua. President Daniel Ortega has cut consular services amid tensions with the U.S. government, leaving grieving families with few options.

Time Is Money

Jose Gallegos worked as a driller and derrickman for Nabors Drilling Technologies, a subsidiary of Nabors Industries, an oilfield services company that operates in more than 15 countries with annual revenue of roughly $3 billion.

Gallegos had been working two-week shifts in the Permian Basin, far from his family in the Rio Grande Valley. But in May 2024 he was working closer to home, in Karnes County in South Texas, as a derrickman on a drilling rig. Nabors was drilling a well for Marathon Oil, which has since been acquired by ConocoPhillips.

Gallegos was high up on the drilling rig as the temperature peaked at 101 degrees and the heat index reached 114. He labored in full sunlight, wearing coveralls, a harness, a hard hat, gloves and steel-toed boots, a later OSHA investigation noted. Gallegos overheated and passed out on the drilling platform.

His coworkers struggled to get him down to the ground as he got hotter and hotter. By the time Gallegos was loaded into a waiting ambulance, he had died.

At the hospital, his core body temperature was measured at 108 degrees.

Nabors’ heat illness prevention program required breaks every hour when the temperature passed 90 degrees. But co-workers later told OSHA inspectors that Gallegos did not ask for a break. A lawsuit filed by his family against Nabors Drilling, Marathon Oil and ConocoPhillips disputes this version of events, alleging that Gallegos had asked for help and was ignored. Nabors was drilling through an aquifer and Gallegos was pressured to finish the job as quickly as possible, the lawsuit claims.

“The culture at Nabors was that time was money and that nothing, not even deadly heat, was going to slow down drilling,” McAllen-based attorney Marcus Barrera wrote in the lawsuit.

Research has shown that in addition to being a serious health and mortality hazard, extreme heat undermines worker productivity. Failing to invest in workplace heat mitigation, researchers say, actually costs companies money.

In legal filings, both Nabors and ConocoPhillips denied the lawsuit’s claims. ConocoPhillips declined to comment, citing the pending case. Nabors did not respond to requests for comment.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowDavid Chincanchan and the Workers Defense Project have pushed for the OSHA rule to include mandatory breaks and third-party monitoring to ensure compliance. He said workers shouldn’t have to decide between taking a break and finishing a job quickly to satisfy their bosses.

“The more the breaks are explicitly mandatory, paid and scheduled, the more effective the policy will be,” he said.

Heat Deaths Often Go Undercounted or Unreported

OSHA determined in its investigation of Danny Nolasco’s death that his employer put him and his coworkers at “increased risk of harm” from heat exposure because the construction company did not have a heat illness prevention program, acclimatization periods or training to help workers identify heat illness and injuries.

People who are new to working in hot conditions are at elevated risk of heat-related illness. Physicians emphasize that workers need to be “acclimatized,” eased into hot working conditions so their bodies have a chance to adjust and learn how to thermoregulate.

Compounding the risks from heat is a misconception that otherwise healthy people don’t want or need rest, said Rosemary Sokas, a retired physician and emeritus professor and occupational health expert at Georgetown University.

That idea is “missing the whole point,” said Sokas, who testified in favor of the federal heat rule.

“Young, healthy, strapping people are at risk if they overdo it,” she added.

A medical examiner ruled that the cause of Nolasco’s death was “undetermined,” noting that his core body temperature—about 101.3 at the time it was measured—was lower than would be expected for heat stroke. The medical examiner wrote there wasn’t “sufficient evidence” to attribute the death to hyperthermia.

Christina VandePol, a physician and former coroner from Pennsylvania, reviewed the autopsy for Inside Climate News and said she felt it was thorough. While she agreed with the “undetermined” designation, she said that doesn’t rule out heat as a contributing factor in Nolasco’s death. And depending on the delay before his temperature was taken, it could have been higher at the time of death, VandePol said.

VandePol said heat is often overlooked in death investigations.

“When I look through medical journals or training seminars for death investigators, that’s not a topic that’s front and center right now,” she said. “I think we’re missing a lot of heat-related or heat-contributory-factor deaths through the medical system.”

The role of heat in workplace fatalities often goes unexamined. Inside Climate News and The Texas Tribune previously reported on the death of a landscaper in Austin, José Mario Calles, who showed symptoms of heat illness and collapsed at work in May 2020. His employer did not report the incident to OSHA. Calles spent two nights at the hospital, then returned to work. Within two weeks he died on the job of a heart attack, an outcome that heat stress can trigger.

“I think we’re missing a lot of heat-related or heat-contributory-factor deaths through the medical system.”

— Christina VandePol, a physician and former coroner

Jordan Barab, OSHA deputy assistant secretary of labor during the Obama administration, said some workplace fatalities are attributed to natural causes—which do not necessarily spark an OSHA investigation—without sufficient evidence.

“I’ve seen plenty of cases that are alleged to be natural causes, which have turned out not to be natural causes,” Barab said.

Do Workplace Heat Safety Regulations Work?

State Rep. Dustin Burrows, a Republican who represents the Texas Panhandle, authored HB 2127—the so-called Death Star bill. He became the Texas House speaker in early 2025. Burrows’ press secretary, Kimberly Carmichael, told Inside Climate News that the law does not prevent employers from meeting national standards, but provides “clarity and consistency” across the state.

“OSHA remains the proper authority for setting and enforcing labor standards and continues to develop national guidelines for heat injury and illness prevention that apply uniformly across all levels of government, without the unnecessary confusion and duplication of overlapping local mandates,” she said.

Carmichael did not respond to questions about the death of Ethan Mackay of heat stroke, which occurred in Burrows’ district in 2024, or whether the House speaker supports a federal heat rule.

Trade groups for construction businesses have advocated for HB 2127 and similar bills and filed comments critical of the proposed OSHA heat rule. Like Carmichael, industry supporters argue that HB 2127 protects companies from having to navigate different rules across the state, not only related to heat safety.

Mark Roach, a board member of Associated Builders and Contractors Texas, a construction industry association, testified that the bill would reign in “rogue municipalities.”

The National Federation of Independent Business’ Texas state director, Jeff Burdett, said in an emailed statement to Inside Climate News that HB 2127 “helps small business owners better comply with regulations, rather than being burdened by the complexity of multiple layers of guidelines over their business practices.”

A federal heat rule would mean more consistent regulations across the country. But in a public comment, NFIB Small Business Legal Center executive director Elizabeth A. Milito said the group opposes that proposal, too.

“Americans in general can take care of themselves in the heat, without the aid of a government agency commanding them to find some shade, drink some water, and rest occasionally,” Milito wrote.

It’s estimated that more than 14,000 Americans have died directly from heat since 1979.

Extreme heat harms every system in the body, including impairing people’s ability to think clearly and understand the danger they are in.

“We’re talking about very basic standards,” said Ana Gonzalez, organizing and advocacy director at the Texas AFL-CIO. “This is a basic human right, the ability for you to stop and drink water and be in the shade. It’s just insane to me that this is a debate.”

Members of unions like those in the AFL-CIO can organize for safety standards in their contract negotiations, Gonzalez said. But Texas is a right-to-work state, hostile to labor organizing, and none of the six deceased workers was in a unionized workplace.

There’s clear evidence that heat rules work.

An October 2025 study by researchers at Harvard University and the George Washington University reviewing OSHA injury data from 2023 found that more injuries occur nationally across nearly all industry sectors—both outdoor and indoor work—when the heat index is 85 degrees or above, accelerating even more above 90 degrees. The researchers found that nearly 28,000 workplace injuries can be attributed to heat annually.

“This is a basic human right, the ability for you to stop and drink water and be in the shade. It’s just insane to me that this is a debate.”

— Ana Gonzalez, Texas AFL-CIO

The researchers also found that workers in states with workplace heat standards, like California and Colorado, had a lower risk of injury on hot days.

When the heat index went from 80 to 105 in states without a heat rule, employers reported 16 percent more injuries. In states with heat rules, the increased rate was half that, at 8 percent.

“It’s actually remarkably strong support for doing something,” said Gregory Wagner, an adjunct professor of environmental health at Harvard and one of the study’s authors. “Doing something will be helpful [and] reduce injuries.”

Given that Texas has banned cities from regulating worker safety and there is little political will in the Legislature to address the risk statewide, labor advocates say federal regulations are urgently needed.

“We want to have the local protections, we want to have the state protections,” said Workers Defense Project’s Chincanchan. “But I think what is really needed in this moment is a national heat safety rule.”

OSHA accepted comments on the draft rule through the end of October. The agency did not respond to questions about its timeline for the proposal.

Walle, the state representative, said if he is elected to another term he will re-introduce legislation to protect workers from the heat. That means waiting until 2027, when Texas holds its next biennial legislative session. Despite the setbacks, he said he isn’t deterred.

“Common decency should prevail,” he said.

The Texas economy, Walle added, relies on immigrants who work in dangerous industries for little pay.

“I wish that the state leadership, the Republican leadership, would pay attention to the working-class people that are actually building this economy,” he said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,